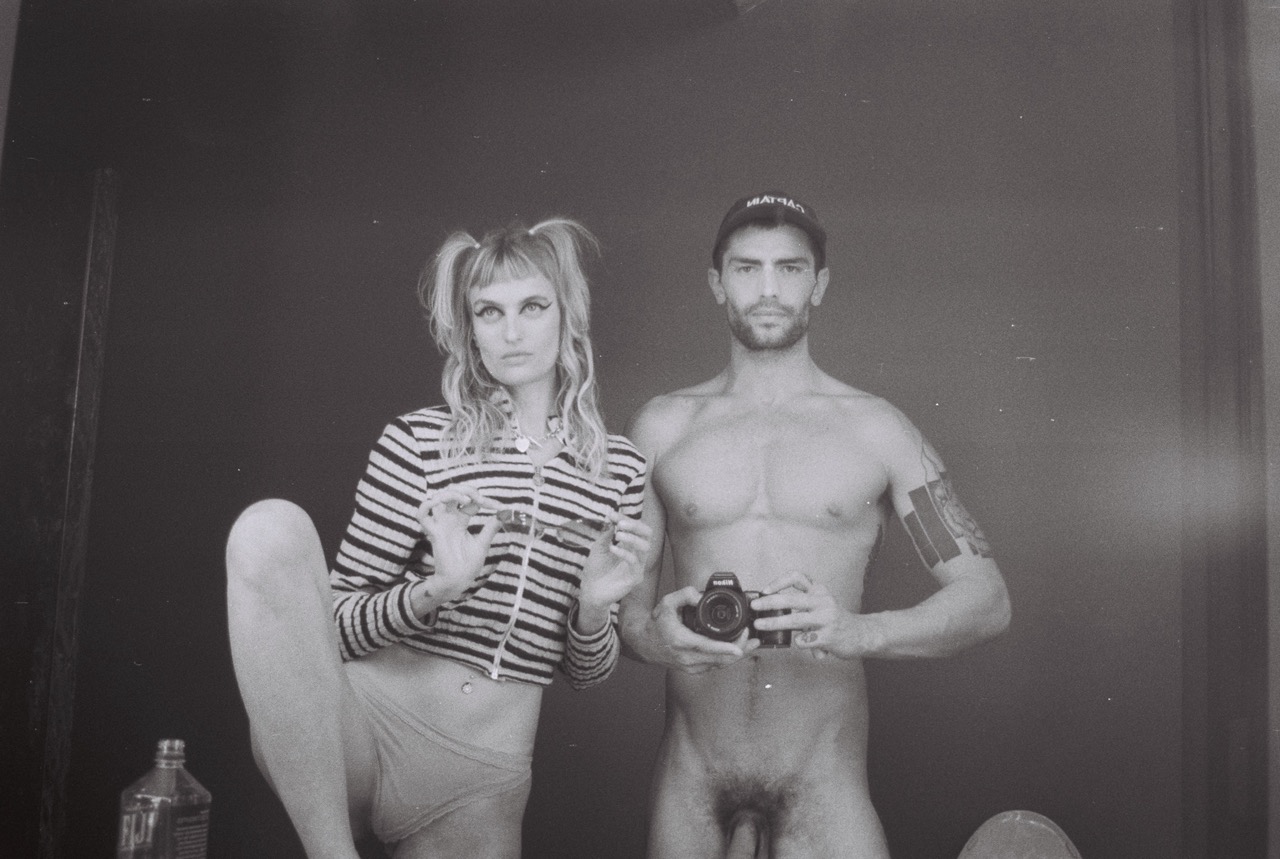

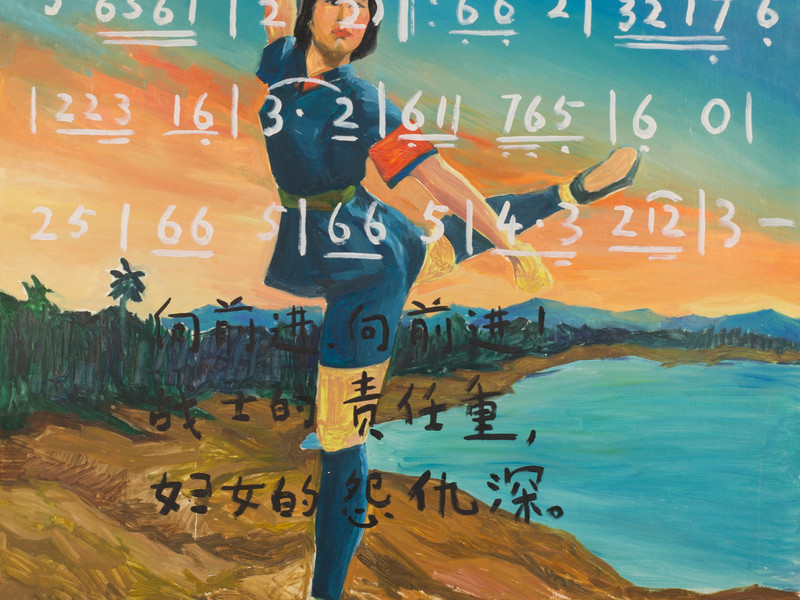

HYSTERIA

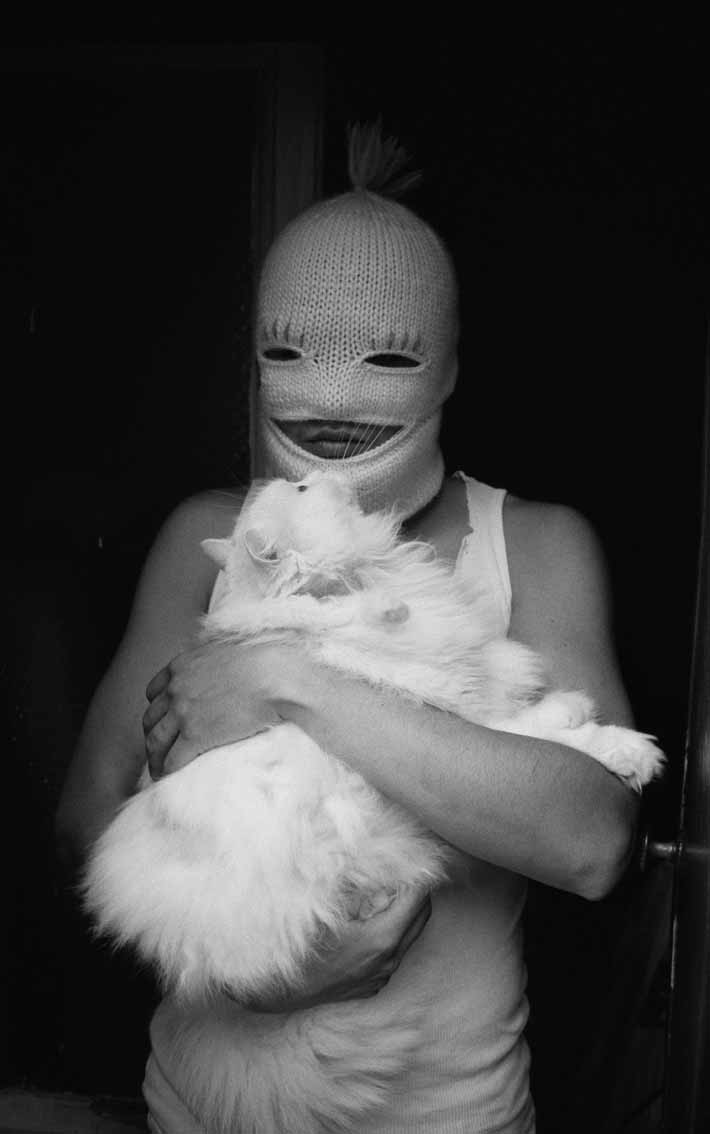

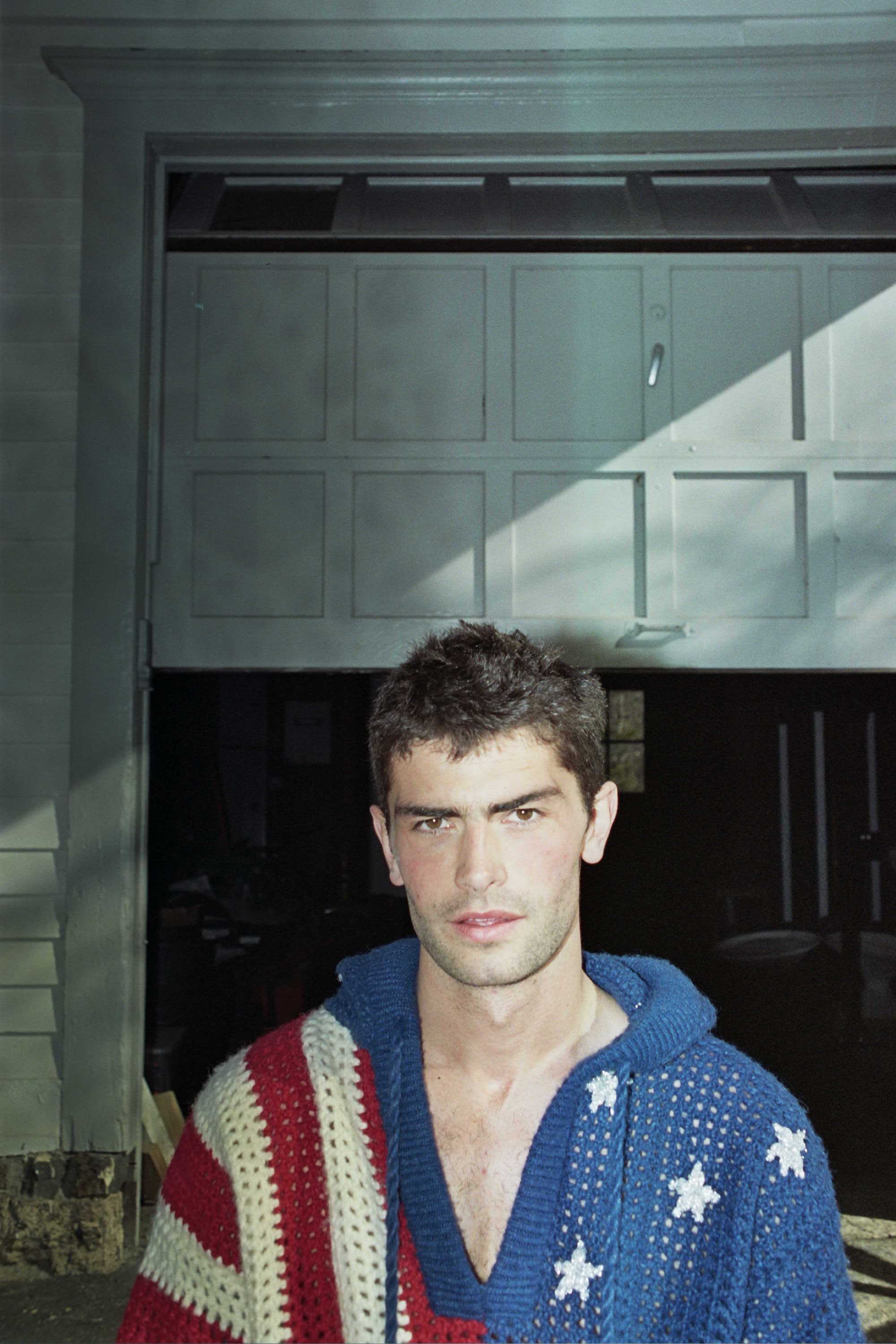

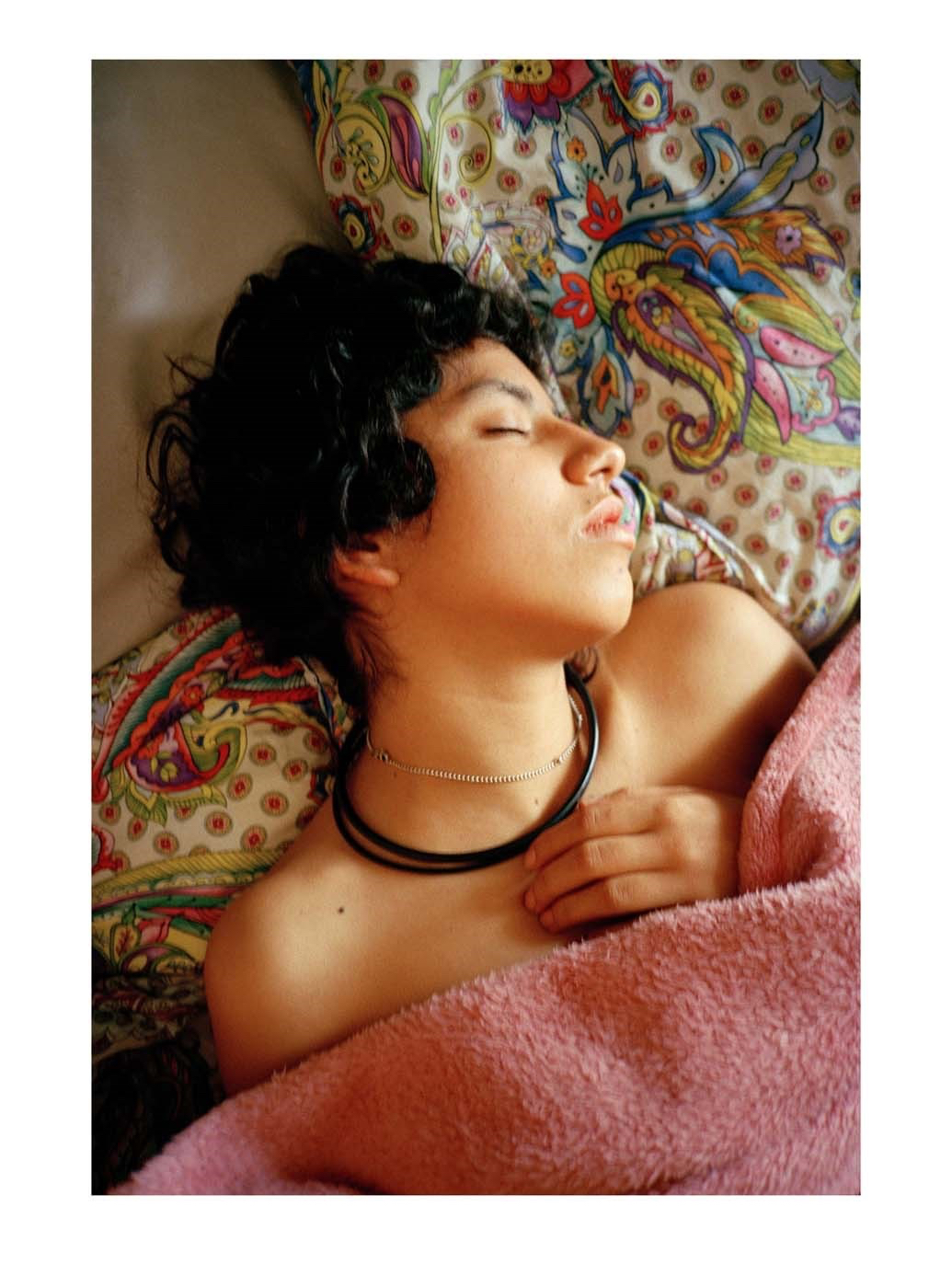

It is these very questions that Sicher explores in her first solo exhibition, Hysteria, which explores one muse in particular: her best friend, Samantha, as well as in her first photo book, Progreso 110, which chronicles the life of her four roommates during her time in Mexico City. While the exhibition was initially meant to supplement the book, Sicher soon realized that it was a beast all of its own, encapsulating the larger idea present within Progreso.

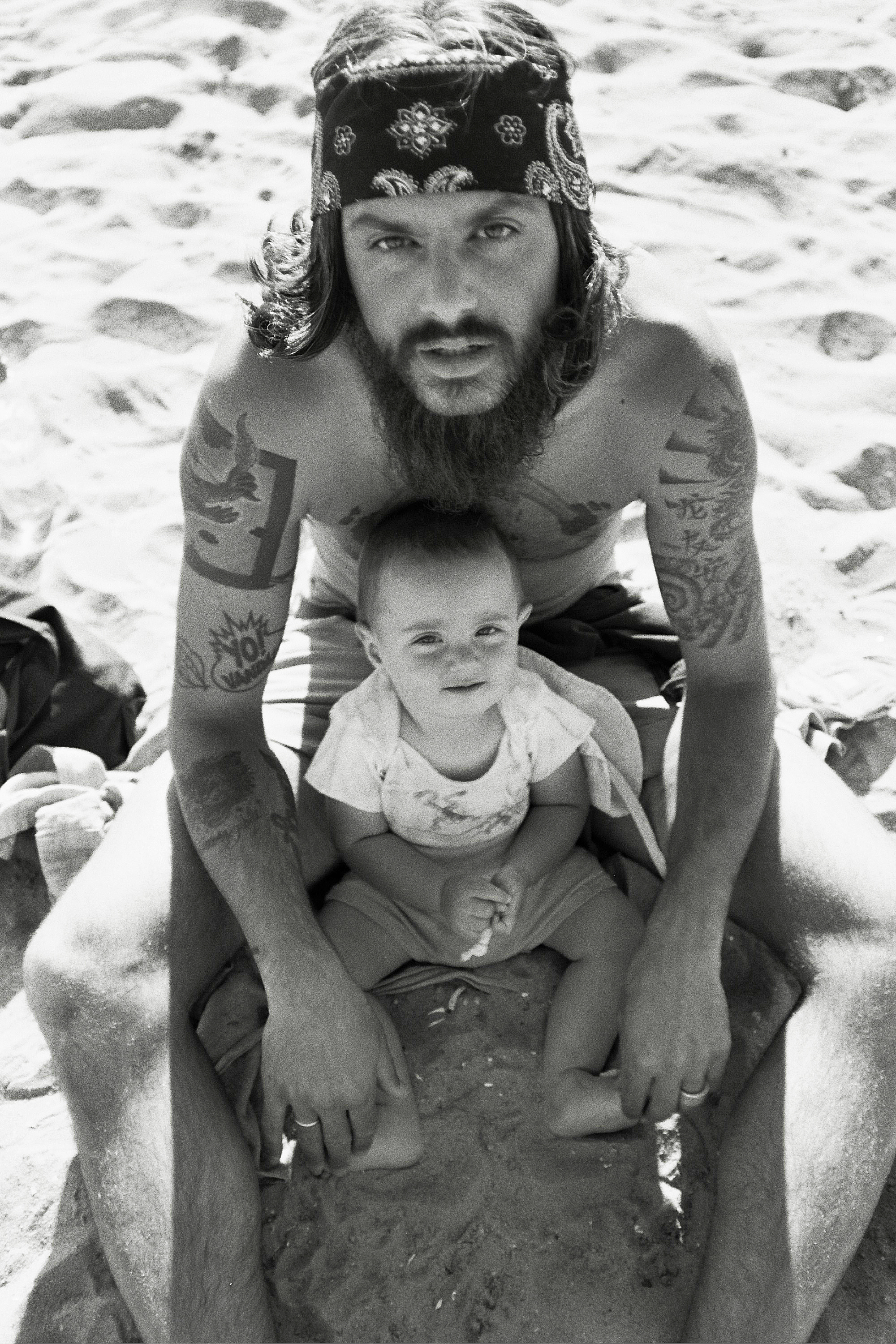

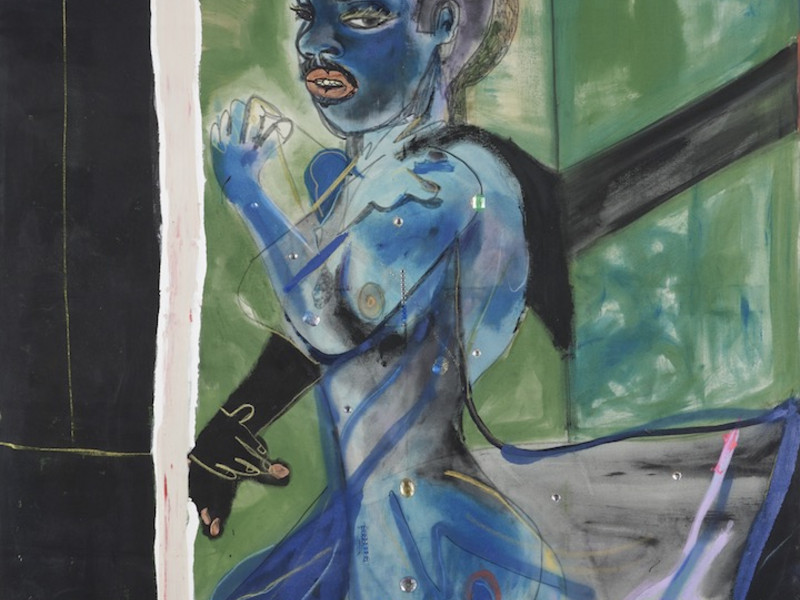

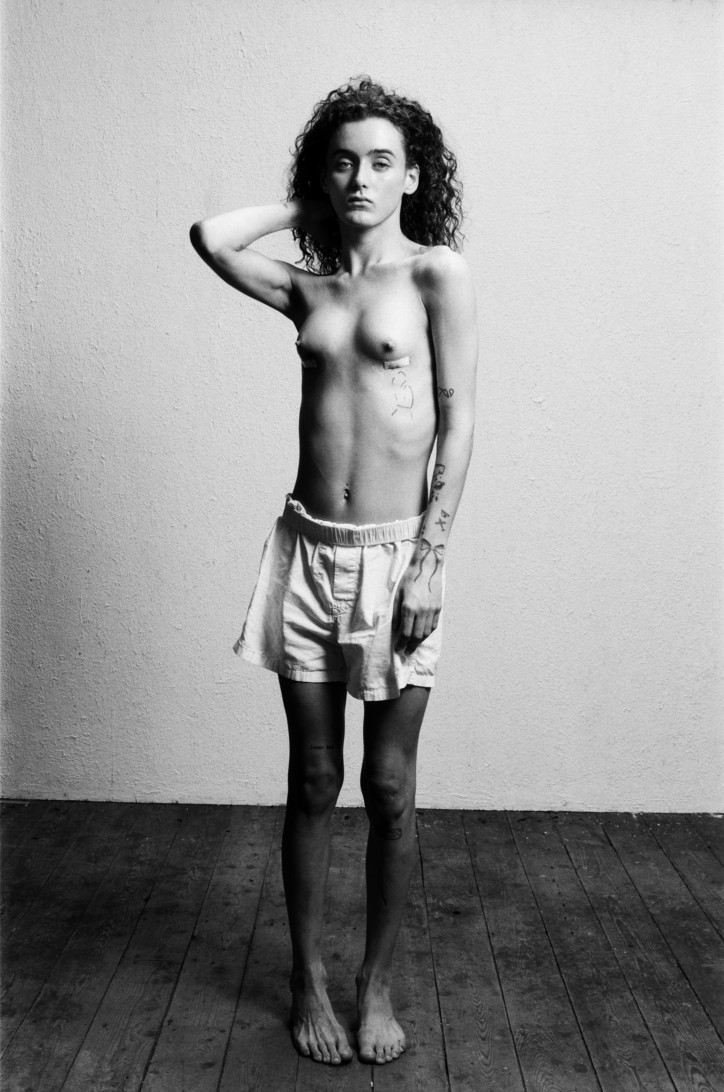

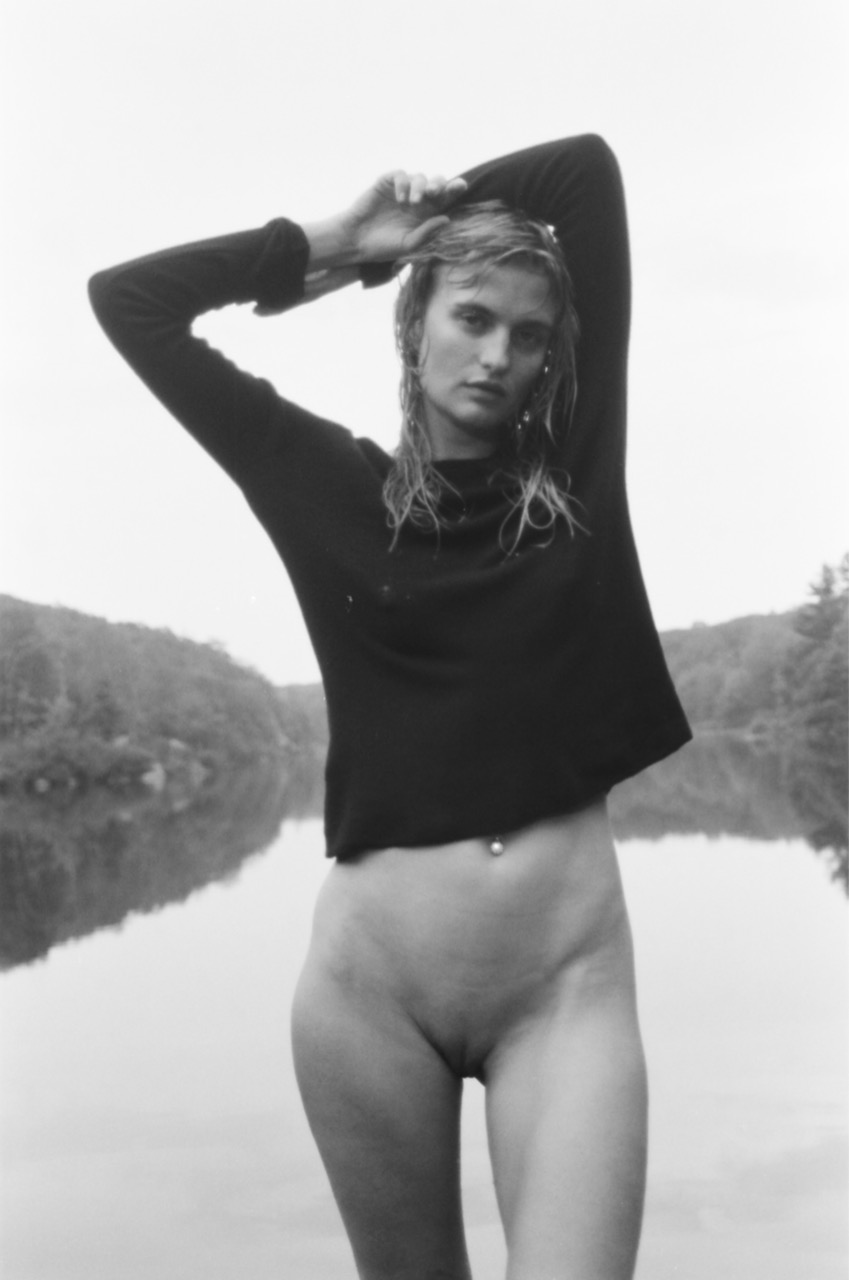

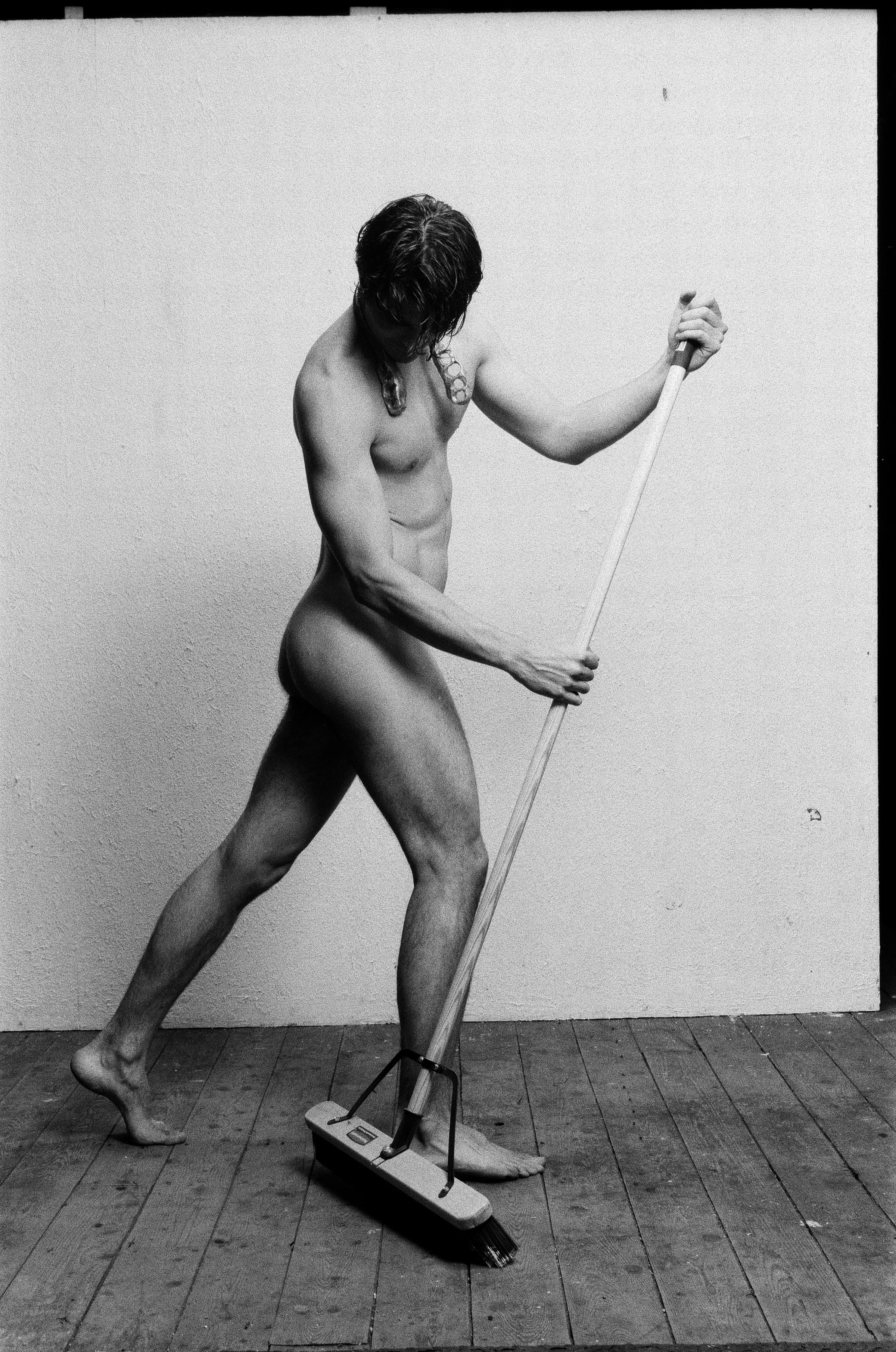

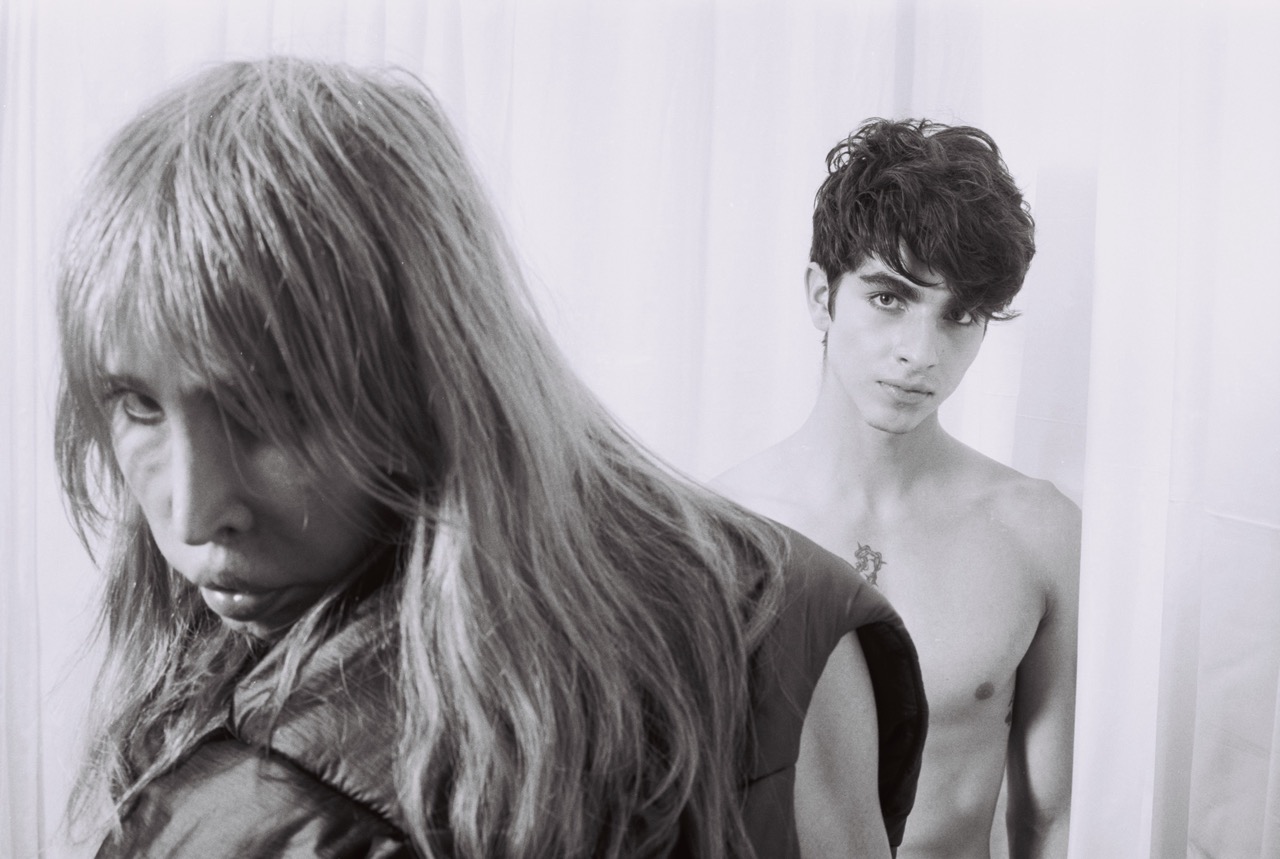

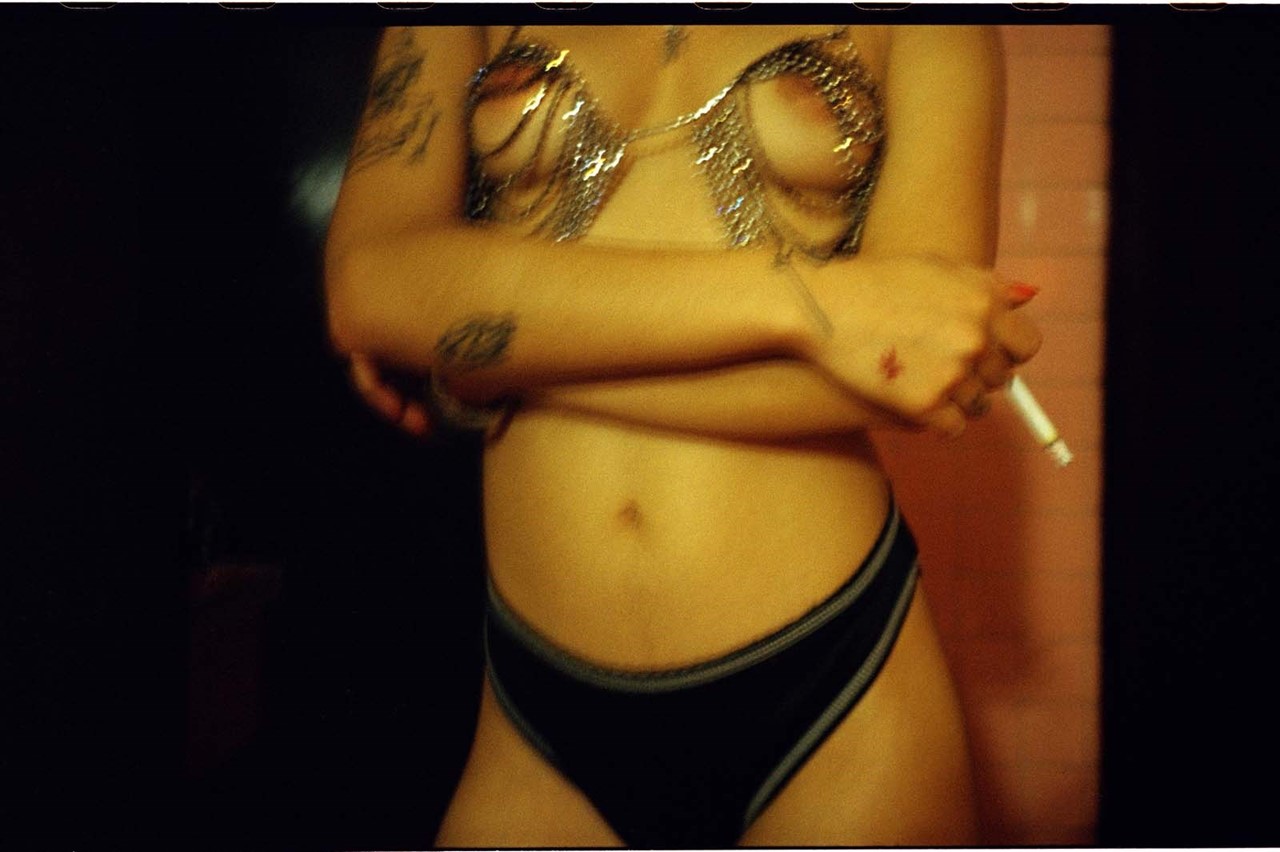

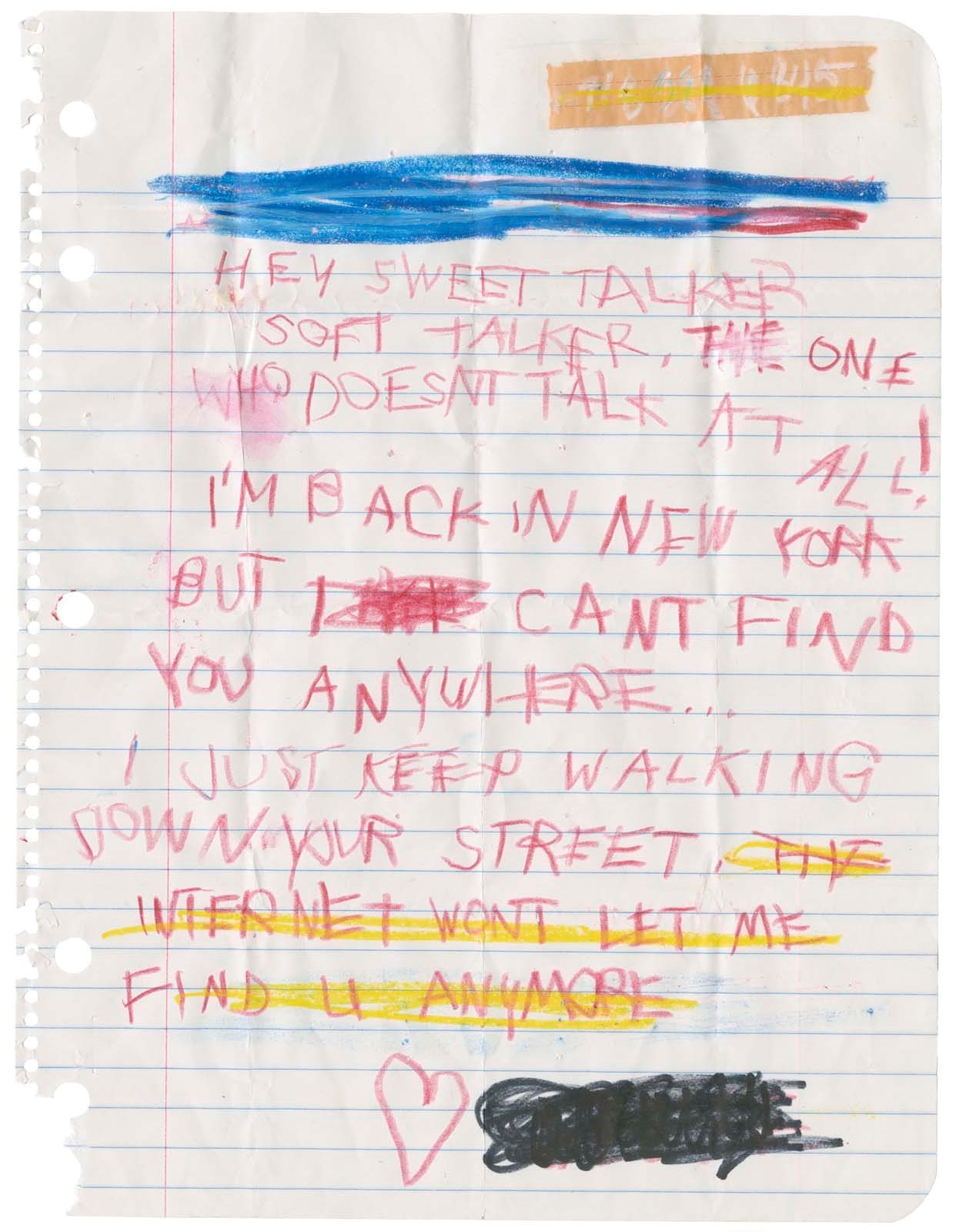

The two explore the dialogue between the photographer and their subject, taking that relationship one step further. The book itself offers a wealth of mediums, from letters and emails to texts and screenshots, all intimate fragments that harmonize into a physical manifestation of her friendship with each respective muse. As a female photographer, her unique and singularized insight into the complexities of capturing the female form create a space in which her muses are able transcend the realm of object—they are no longer merely a face, a body, a subject; but rather, a dignified woman as much part of the creative process as Sicher herself.

Read our interview with the photographer below, and don't forget to grab a copy of Progreso 110 when it hits the office Newsstand.

What is the relationship between your show, Hysteria, and the book, Progreso 110?

The book came first. So, for the show, I initially wanted to throw up a lot of prints and photos from the book, but then I realized that I wanted the show to be something bigger than just that—I wanted to include other pieces of my work that, for me, kind of explored the same themes. I think that ultimately the book is a smaller piece of a larger idea, and the show sort of encapsulates the larger idea.The text for the show is literally an email I wrote to myself in the middle of the night because I had no more space on my tiny little computer. That’s relevant because if you look through the book, there are letters, journal entries, text messages and emails, as well. So, the text for the show is an extension of my exploration of various mediums.

The text was my way of trying to figure out how I really want to talk about the show and the book, which was a really funny process. I was kind of confused when I started writing it because it dawned on me half way through that maybe all of this content was just for me—intimate moments that I only wanted to share with Samantha, one of my closest friends and the muse and protagonist of the whole narrative. Then I realized through writing the text that it was equally as important to share these moments with everyone else as it is to share between just the two of us. I wanted to keep it in the format of an email because of its relevance to the way that her and I actually communicate, and the way that I show communication in the book in general. So, it ended up like a letter—that’s what it’s called: “Note to Self, to Samantha, Note to the World?”

I like that the book came first and the show was kind of like your means of grappling with how you wanted to present the work—it makes both projects feel so organic.

Yeah, I mean the show was almost supplemental. But then it was like ‘No, okay,’ because I realized that actually a large part of the book was about my projection onto a space—projecting a narrative onto another person—so there was no other way to communicate how much her presence and her voice is part of it; the things that we make together and the ideas that she’s brought to the table. The whole concept of Hysteria started out as this idea that I was sort of obsessed with—an inexplicable sensation that can come with so many different feelings. The history of the word suggests that hysteria is a condition that’s almost exclusively female, and about people not being able to comprehend the complexity of quote on quote ‘women problems.’ So, personally, I found the associations of the word to be kind of funny, because nobody really looks at the word like that anymore. It was in the process of putting my show together that I realized that staples of my work are these strong women who have been really big parts of my life and parts of my work—none of these women have ever been just a face that has since disappeared, you know? So, Hysteria is not really about the book—it’s more about the content, for me, and the relationships between the people that I’ve photographed, and what it means to have a muse, and what it means to have all these female bodies around you.

I really appreciate the mixed-media format. In Progreso, all of the pictures are so different—it’s almost like they could’ve been taken by different people entirely—yet the sentiment behind each image is so similar.

Yeah, which is kind of what I like about it. I studied photography, I’ve worked in a darkroom, I love all that nerdy stuff.

Ugh, the dark room scares the shit out of me.

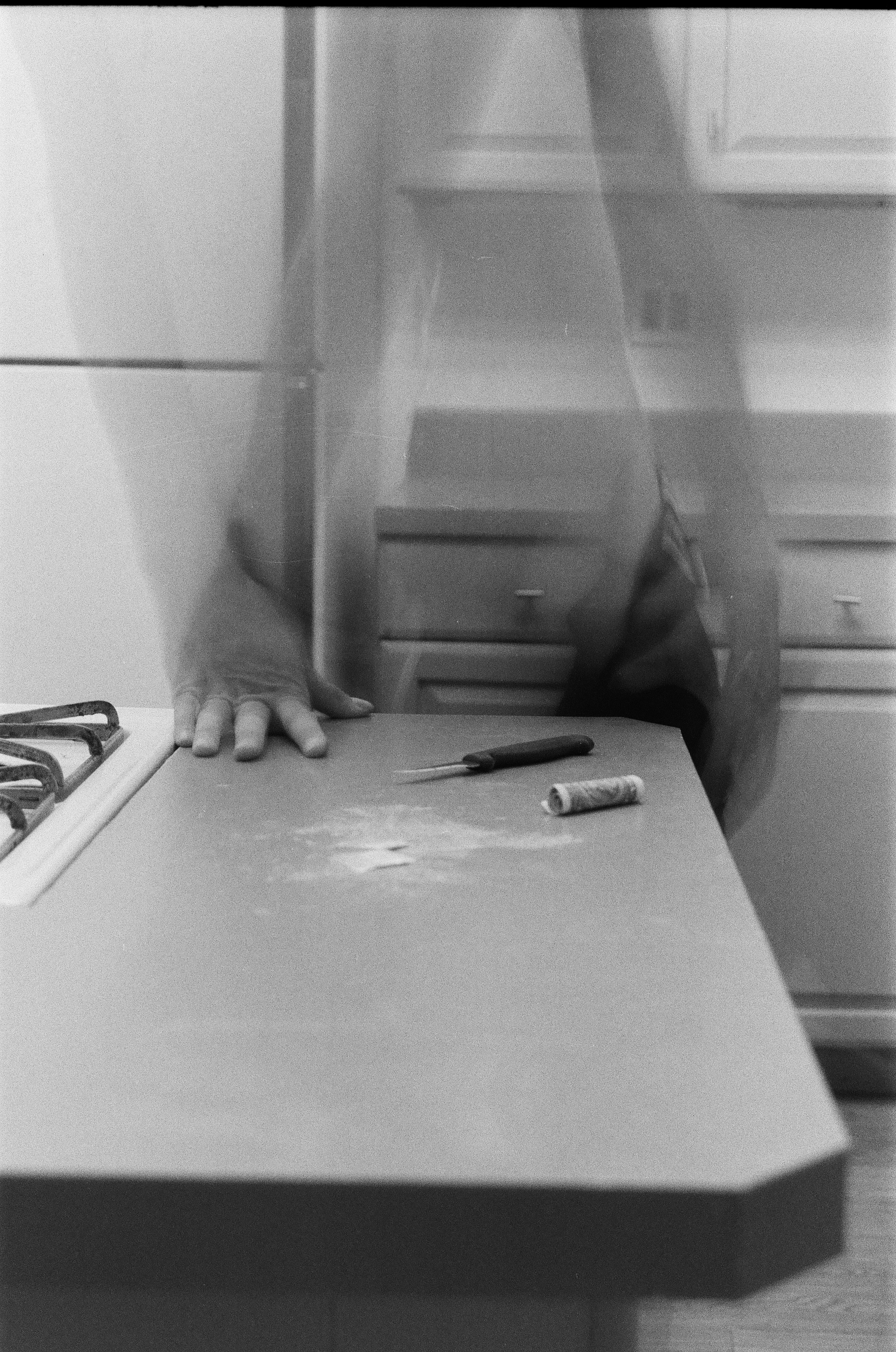

That’s my safe space! I’ve studied all of those processes before, and they’re all really important to me in terms of my own process and how I’ve learned how to take photos. But at the end of the day, it doesn’t really matter to me if someone is shooting with a digital point-and-shoot, or a film camera, or your iPhone—the tool doesn’t really matter. I mean, it’s cool to be able to explore and have access to all of these different things, but I think the point of the book is showing that all of these forms of making images can exist in a single place. It’s sort of like anti-purist photography—not that I would label my work as that, but I’m just like, ‘Fuck that purist philosophy.’

In this case, anti-purism in the photographic realm is sort of aligned with the way I feel about the format of the photographer and the subject, or the format of the photographer and the muse, and how it’s been placed historically. It’s the same thing with a beautiful photo book and how it’s presented, and what is taken seriously—I want this person to have a voice and I want that voice to be shown here. It doesn’t need to be just one-sided. Progreso 110 is obviously not the most pristine, beautiful photo book in the world, but I still want it to be taken seriously. The iPhone stuff in there is not meant to be kitschy—it’s there because without its inclusion, I would be avoiding a part of the process, and in that way, it works hand-in-hand with the narrative as a whole.

I definitely agree with that. Any piece of art, no matter the medium, should be reflective of the relationship between the painter and the painted, and how you can communicate that flow of energy.

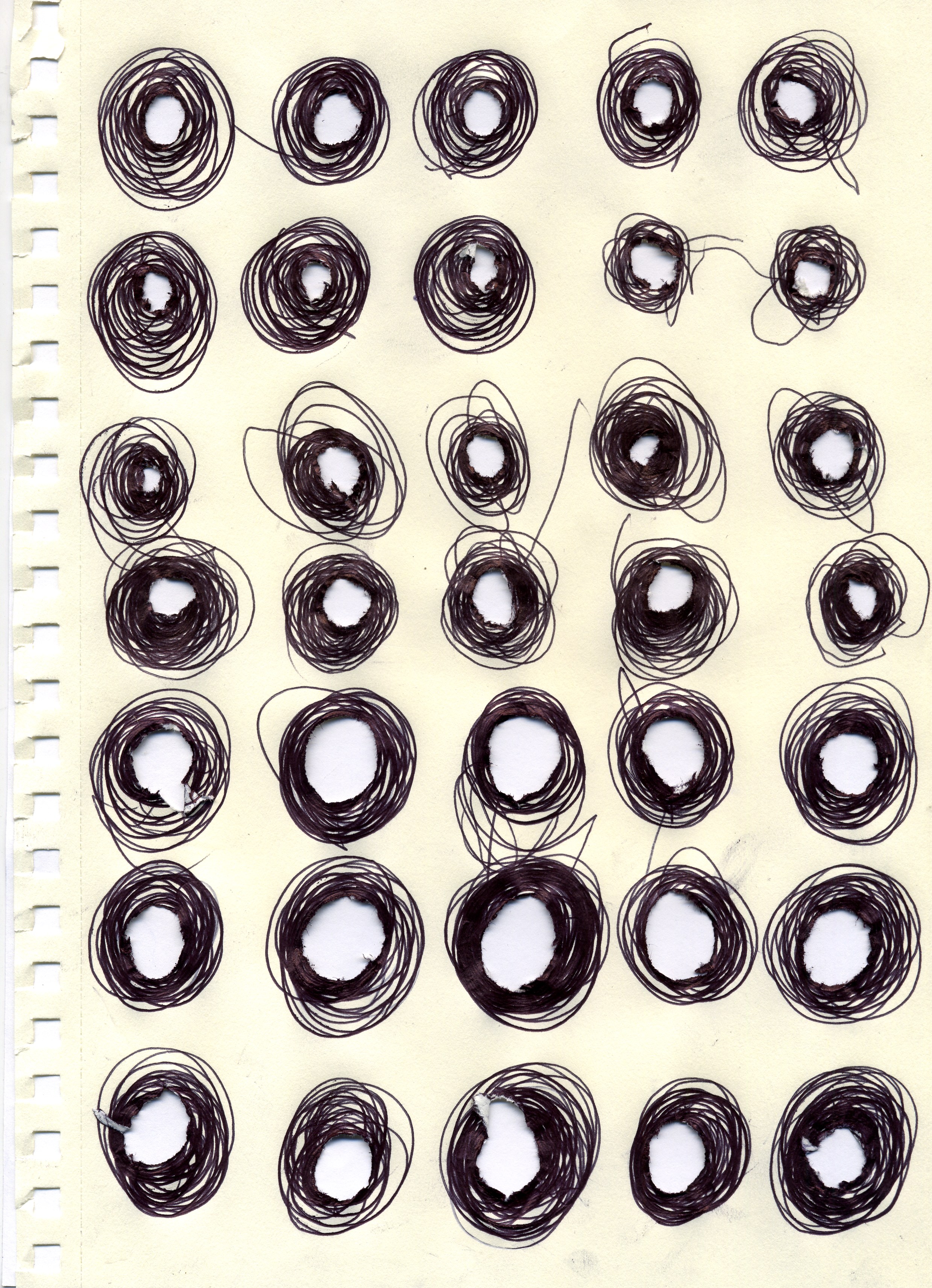

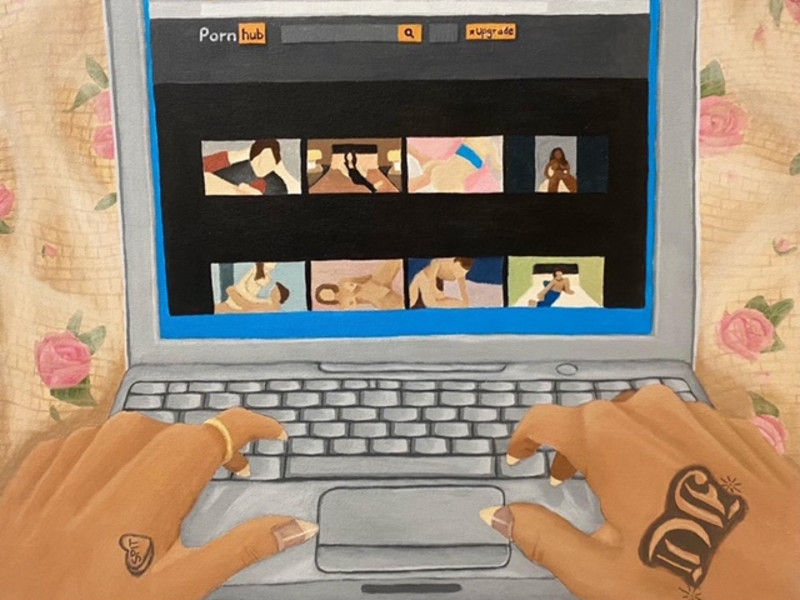

Yeah. Like this, for example, is interesting to me [referring to a series of Instavideo screenshots]. My friend, Angel, who was one of the girls who lived in my apartment, sent me these videos one day on Instagram. Now, on Instagram, I think you have the option of saving videos or whatever, but at that time, the videos would disappear after a couple seconds, and because I loved the videos, I took screenshots of what Angel sent me. Only later did I start to think about how everything these days—and this is a part of a larger conversation about virtual reality, and that being a big part of reality, but also art—really tries to simulate reality. She sent me the videos and I wasn’t with her, and she no longer had access to what she just sent me, just like the actual moment—a physically fleeting moment—but by taking those screenshots I now have those images.

That was a big conversation in making the book, because I had all this stuff that my friends and I made together. Samantha would always say when we were in the same place, ‘Let’s make virtual photos, let’s video chat,’ and I think it opened up this whole conversation about what it means to take images, to possess images, to whom do they belong. This concept is so important for me because I think there are so many places that images can live and exist. So, it’s sort of like taking the physical image of someone, and then taking an image like this, and having them exist in the same space.

I also feel like every page evokes such a distinct memory, and by that I mean it’s very evident that nothing is in there just to be there—just to take up space.

Thank you. The first edit—I mean there were thousands of photos—but the first edit of the book was 850 photos. And we were like, ‘No, this is too much, this is unnecessary.’ Now, there is roughly three hundred.

I know that you have a very special relationship with Mexico City, and you were born and raised in Brooklyn. So, if Mexico City and New York were people, what do you think their relationship would be?

New York is definitely colder—I don’t mean temperature-wise—and more stressed out. This relationship is so significant to my book, because Samantha and I kind of take the place of representing these two spaces. They’re similar in a lot of ways, because they’re both crazy cities, but they move at very, very different rhythms. Of course, I have a very specific view of the city, but Mexico City is such a huge place that I haven’t even touched on everything yet. In the same way that I started thinking about me and Samantha, which was sort of a joke at first that turned into an actual creative idea, was that they’re kind of like alter egos—very similar, but again, rhymically and emotionally very different. When I think of New York, I think of high-strung, every person for herself, hustling, whereas Mexico is like a big community, and relaxed—at least what I’ve been exposed to. New York is really out there, and Mexico City is very mysterious, there is so much there at is—it sounds bad to say, but underground, or unseen.

What’s so interesting about Mexico City, to me, is that it feels like every zone, neighborhood, district, is basically a different world in a way that New York doesn’t. I feel like that’s a lot of pressure for me to put on Samantha and myself as the ‘spokespeople’ for these two places, but I think that a big part of Progreso is us becoming so close and realizing how similar we are, even though we come from two culturally dissimilar places, and finding really interesting parallels between our lives.

I know I’m friends with someone when we can sit in silence together, but it doesn’t feel forced or awkward. For you, what’s that little signifier of friendship?

When you can poop in front of each other—no, I’m just kidding. I think—and this might tie into the last question, as well, because it has a lot to do with Mexico City and the welcoming that I felt. Here, I have close friends who are like brothers and sisters to me, and we hug and touch each other, and it’s intimate, but I feel like culturally, there is such a difference in the way that people interact.

When I was in Mexico City, there was a lot of touching, there’s a lot of love. I didn’t grow up with a cold family or anything like that, but I definitely noticed that cultural difference—just being hugged and touched by people all the time. I mean, Samantha holds my hand all the time, and it’s just such a funny thing that really made me feel at home, and filled in something that I never really had. Then again, I think that differs between friends and family—it must be something about when you break the ice and realize that someone makes you feel safe; or maybe there’s some sort of information that comes out and your realize, ‘Okay, this person gets me and I get them,’ which is also a funny thing, because I’m almost fluent in Spanish and Samantha is almost fluent in English, but there’s always been a little bit of a barrier between us. But aside from all of these barriers, like language, distance, time zone—to be able to really get that close to someone and actually be able to hear them and understand them is really something. Over there, it just felt like I always had a hand on my back—and I mean this both physically and metaphorically. I always felt supported.

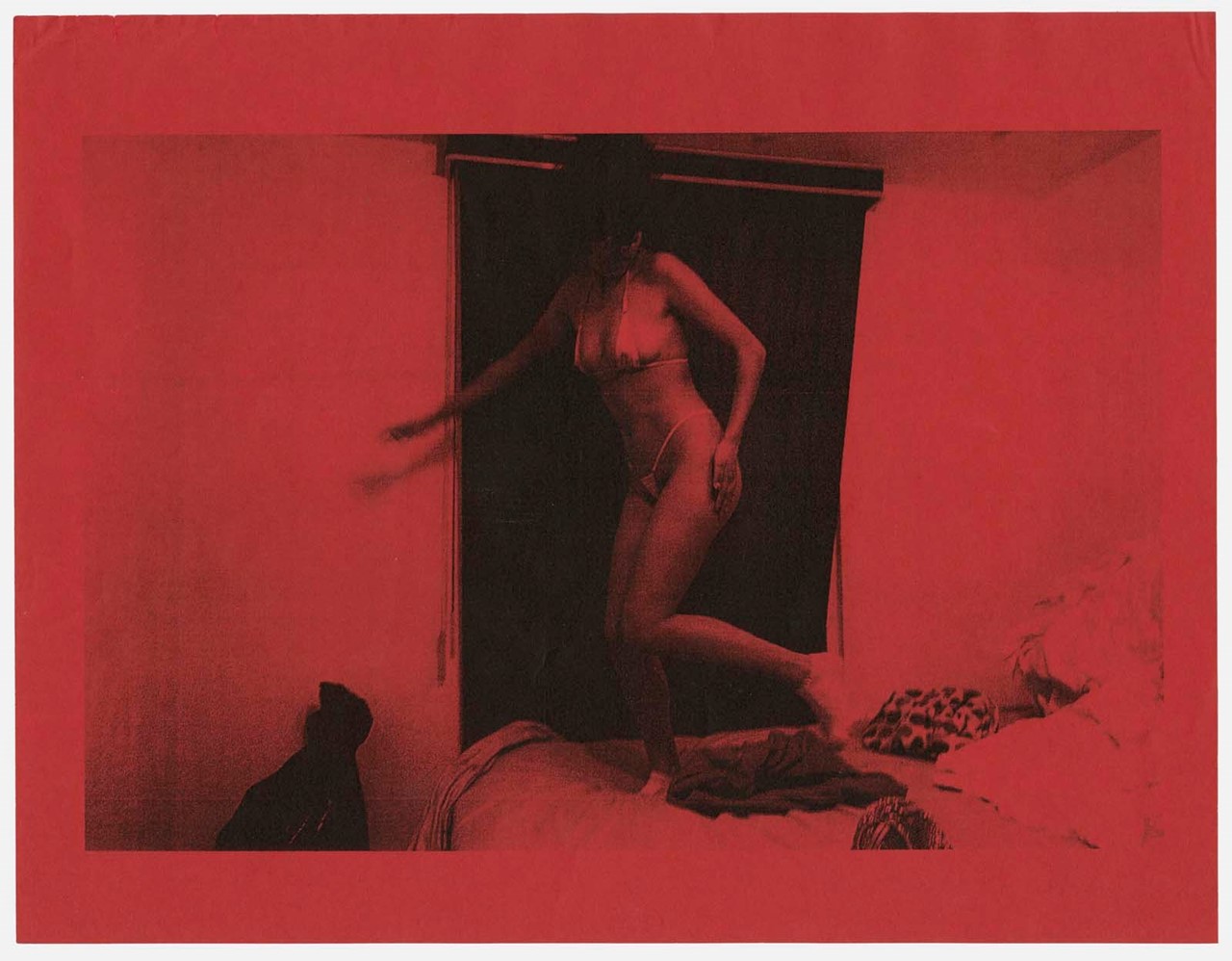

That’s rare. The concept of the muse and the male gaze has always been something you like to explore within your work. As a female photographer who, by nature, understands all of the complexities of the female reality, what do you think the discrepancy might be between the way in which you capture the female body and the way in which a male photographer might do the same?

I was just listening to a conversation about touching the subject on set in fashion photography. I forgot the specifics, but a photographer kept moving the models and touching them without consent, and I just couldn’t believe that this type of situation is still going on. Obviously, I photograph people and I ask if they could move their hand and so on, but I don’t understand that dynamic without asking for consent and an open dialogue. There is just so much entitlement as a photographer—especially as a male photographer. When someone is behind your lense, they aren’t just a model, or a thing, for me—they aren’t just this object that I have complete control over. Even though this sentiment is being challenged a lot right now, it just blows my mind that there’s still not an established dialogue around that, and that you don’t ask people if you can pull their skirt up—you just do it. So, that’s a lot about what the show and the book have to do with for me—the concept of the muse, and that the dialogue doesn’t end there.

I mean, of course I do fashion work, but every photo in this show is a lot more documentary-style, a lot more candid. I just think that that’s what’s so special to me about the work—being able to have that conversation, and the fact that I didn’t do anything without people’s permission. And the dialogue extends even to the end—the final product of showing the work. It’s having that person transcend the space of just the photograph—giving the subject a say in what happens and making them part of the process as much as I can. Just as a woman, I want to represent someone the same way I would want to be represented, and I think that extends to actually showing and selling the work, because I don’t want to sell anything that a person doesn’t want to be sold.

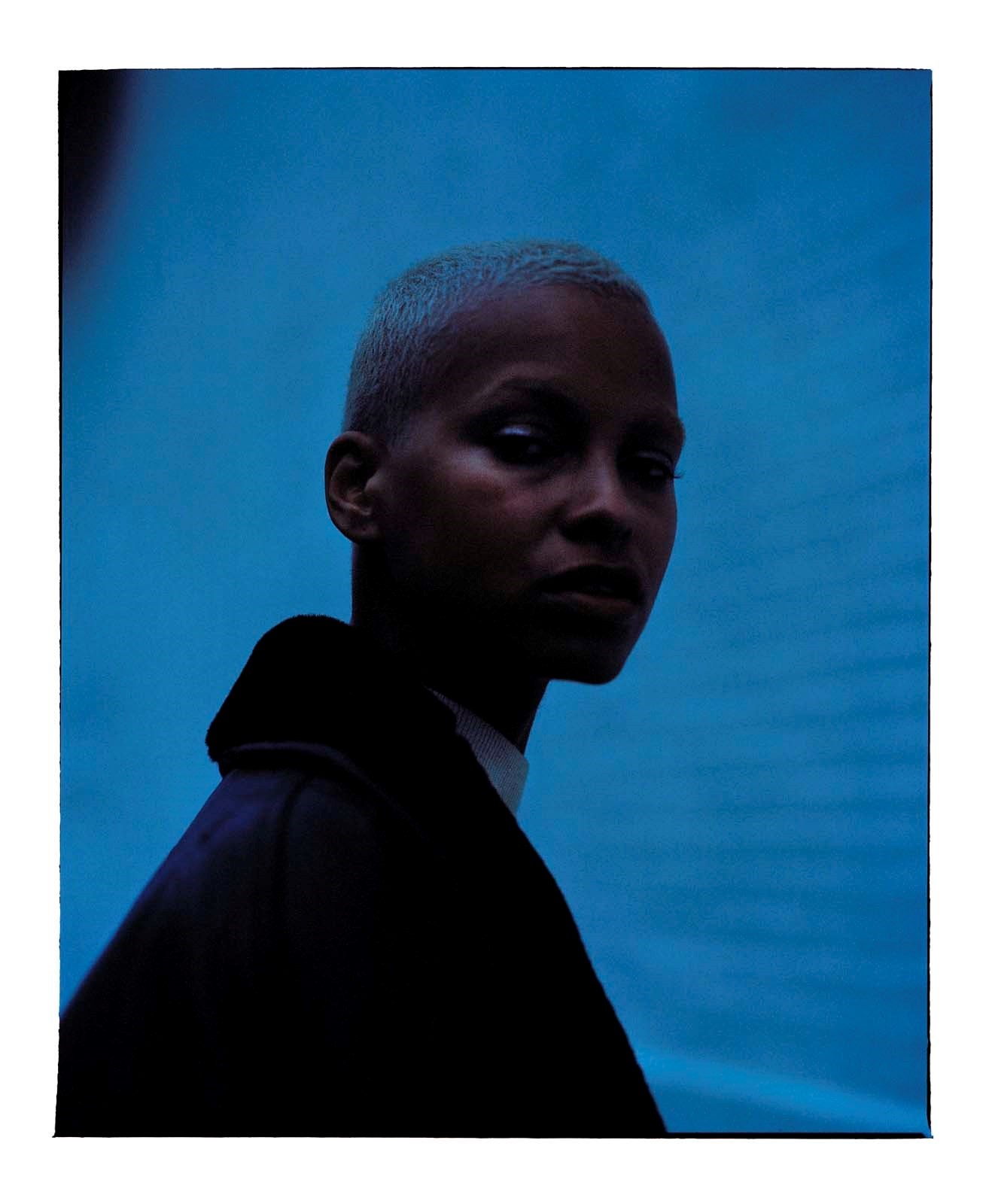

A friend of mine, Laura Sage—she and I have had this constant dialogue about what it means to be taking photos, not just as a woman, but being a white woman taking photos of a black woman, and the idea of profiting off of people's bodies and what that means. She has really helped me start a dialogue around the idea that sometimes work shouldn’t belong to everyone—sometimes work should just be for us. Then we started this whole conversation about how the proceeds and how they will be allocated were to be decided by the subject herself. For me, it’s not about making a profit, it’s about extending the conversation of what a muse is.

‘Progreso 110’ is out now and will be available for purchase at the office Newsstand.