Fine Art Through the iPhone

'Talking Pictures: Camera-Phone Conversations Between Artists' will be open through December 17th, 2017.

Stay informed on our latest news!

'Talking Pictures: Camera-Phone Conversations Between Artists' will be open through December 17th, 2017.

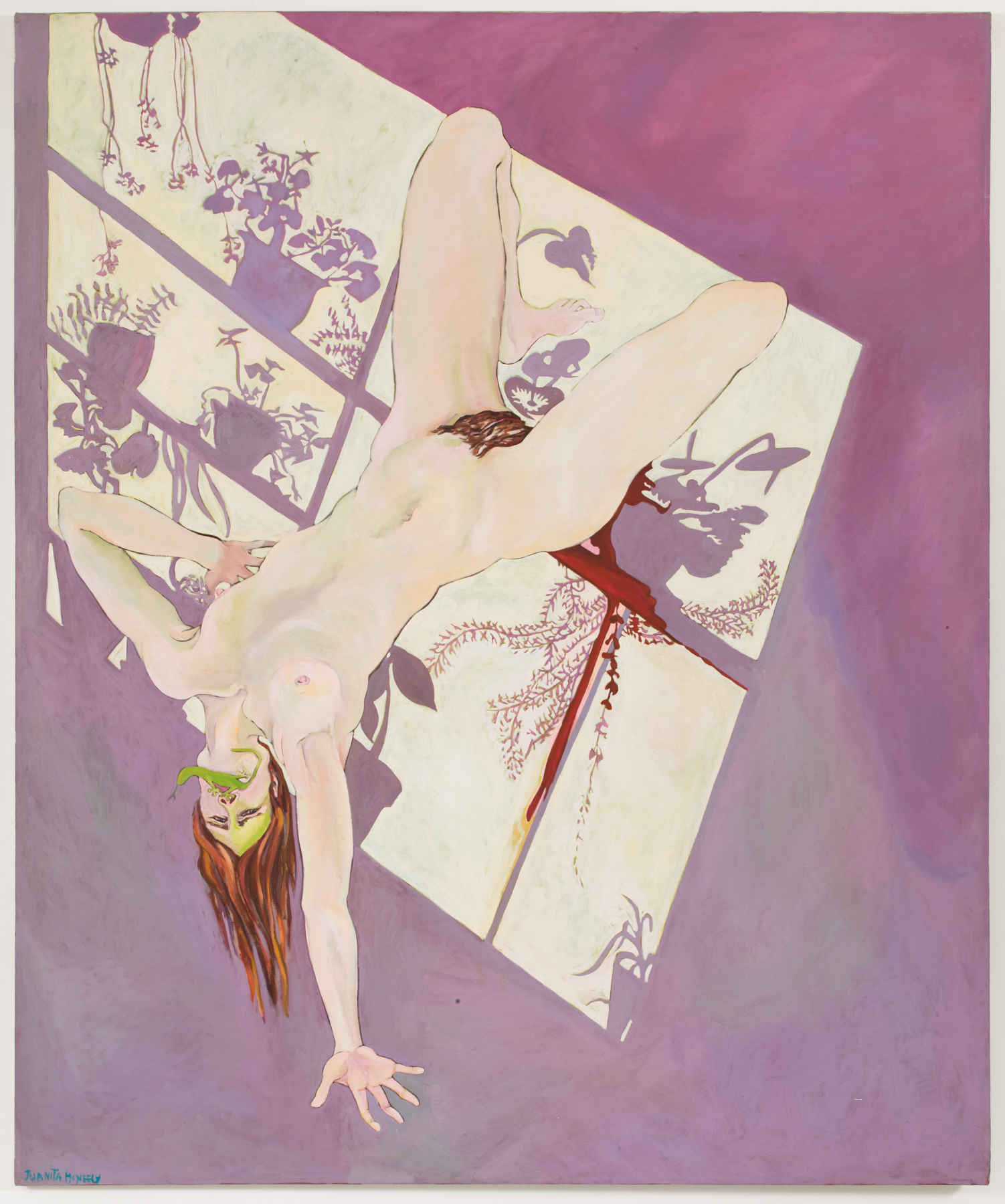

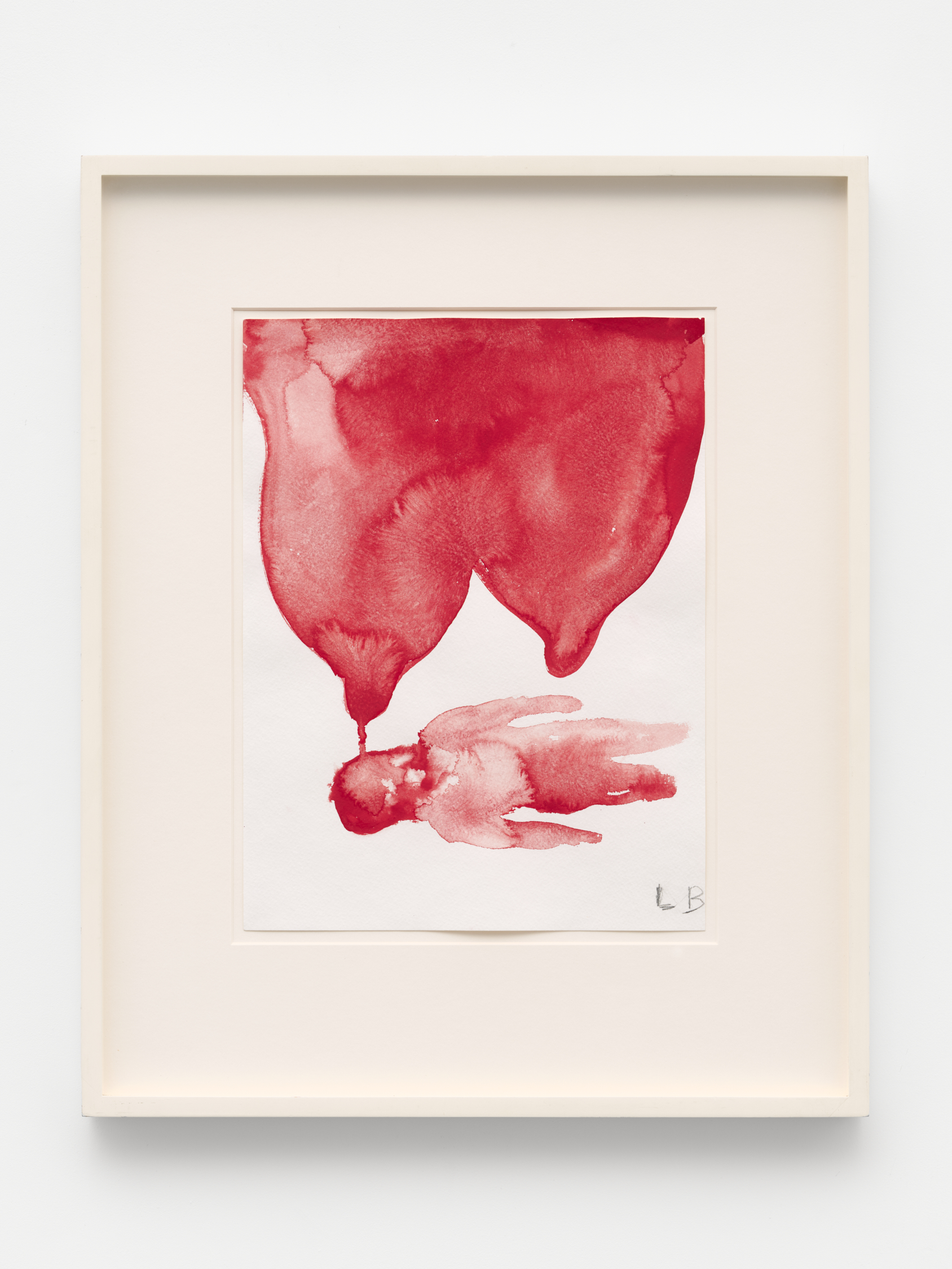

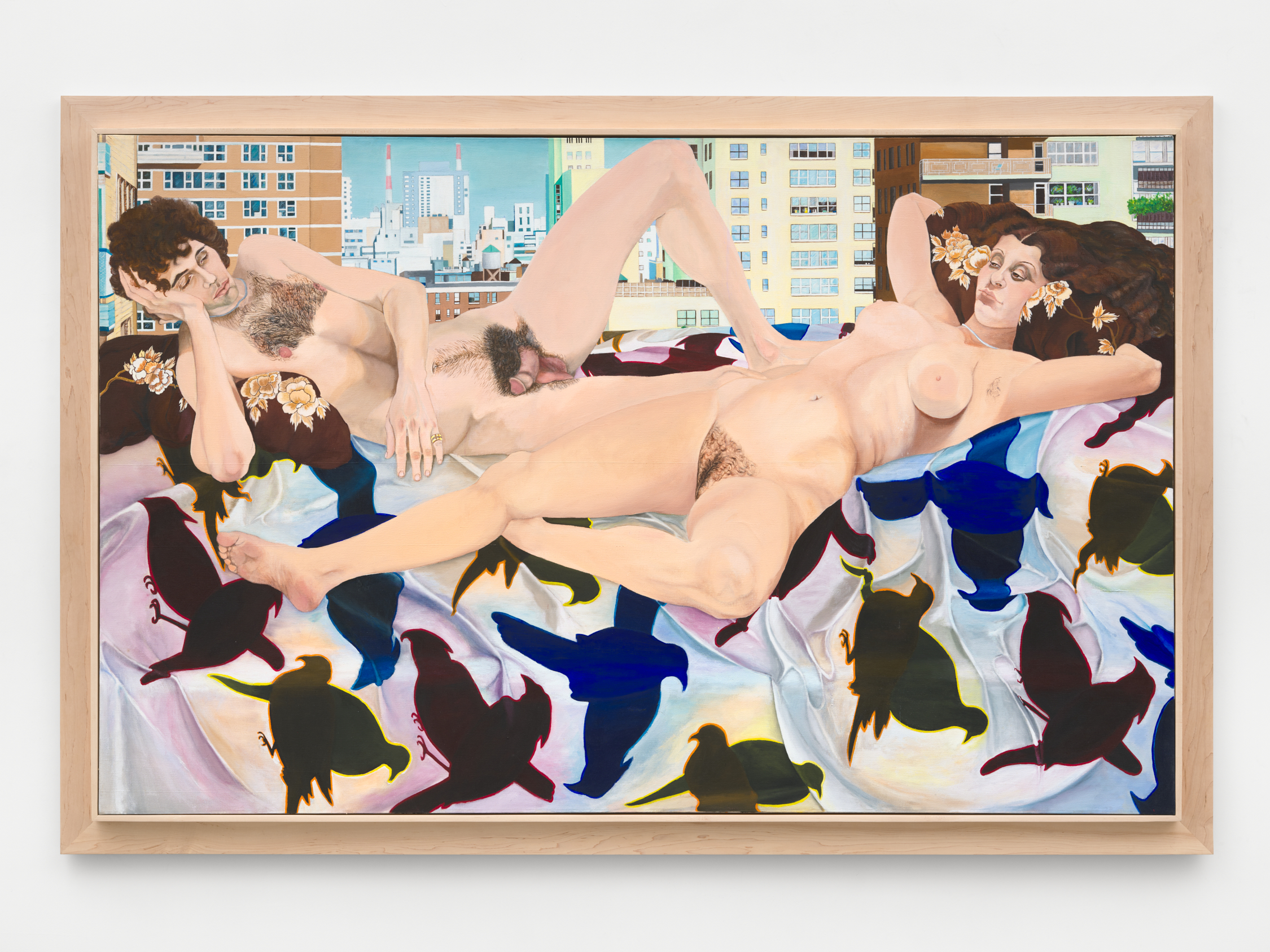

The show’s namesake piece, Anita Steckel’s Giant Women on New York (Coney Island), 1973, is part of her greater Giant Women series. A nude woman, stylistically larger than other figures, lounges outstretched in the water of Coney Island beach. Known for mixing erotic imagery with recognizable landscapes, Steckel protested art history’s double standards by portraying female nudity on her own terms. Her figures take up space both literally and figuratively in her landscapes, emphasising an ongoing uphill battle for women to secure their place in the cannon.

In 1972, a Republican legislator demanded that Steckel’s solo exhibition, The Feminist Art of Sexual Politics, be cancelled, considering her works too obscene for the public. Steckel responded to this accusation by forming the Fight Censorship Group, which would go on to advocate for the right for women to use male nudity and sexual subject matter in their art works, just as men did. While we might like to think this kind of censorship is some far off dystopian reality, it’s all too familiar to the political control we’re facing again today.

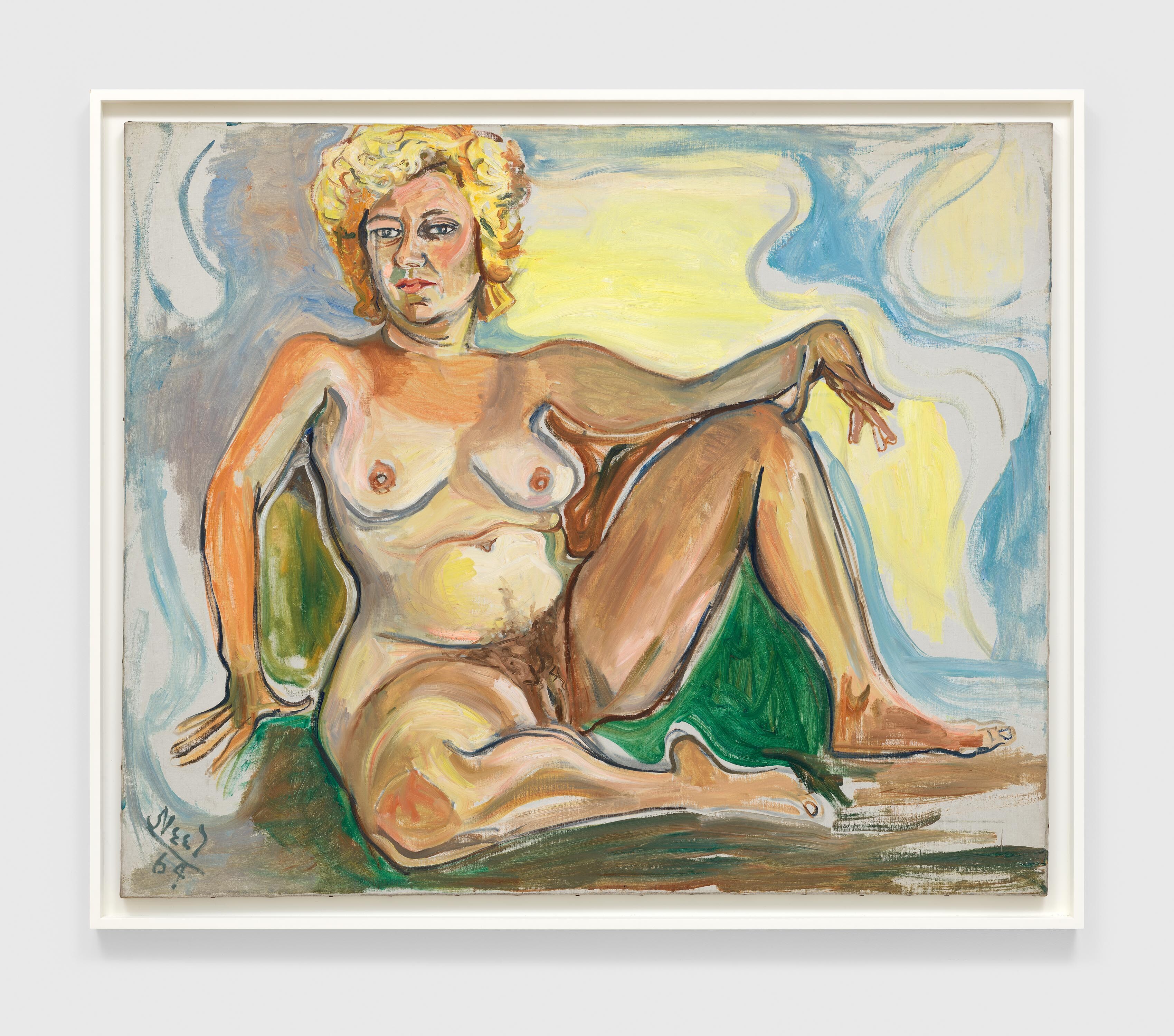

Bringing female experiences to the foreground of painting was part of a larger initiative to give humility and dignity back to the sitters, especially when painted in the nude. Male artists often depicted their models as mere sexual objects or muses, painting them as nothing more than nude flesh, disengaged from personhood. Alice Neel was uninterested in producing the next Grande Odalisque, and opted to humanize her subjects through her honest and raw depiction of the nude figure. In Ruth Nude, Neel’s unforgiving re-examination of the female body takes away an overly idealized exterior. In doing so, Neel provides an opportunity for the viewer to inquire about the sitter’s inner psyche.

This unvarnished approach to the body can also be seen in the work of Joan Semmel, who began as an abstract expressionist and later turned to figurative painting. Her sexually charged imagery was part of a larger second wave feminism initiative for women to explore and get in touch with their bodies as a means of taking back ownership.

Semmel did this by painting her intimate angles of her own aging body, depicting its inevitable changes. In other pieces, she intentionally leaves the face of her figures out of the frame, allowing the viewer to impose themselves into the work. She depicts visible sexual pleasure from a woman’s perspective, outwardly rejecting the male gaze. Bottoms Up (1973/1992), is part of a larger Overlays (1992—96) series, combining an underpainting from her Erotic Series (1972), with later imagery from her Locker-Room paintings (1988—91). Semmel revisits the same themes throughout her life, emphasising the lifelong commitment she has made to her figures.

These women not only refused to sacrifice the woman for the artist, but created a community to support a greater discourse surrounding what stories we highlight in art history. Giant Women On New York seamlessly demonstrates this unending determination to compound the worlds of activism and art, while also revealing how much work there is left to do.

The art landscape is changing quicker than we can keep up with, and with that, our commitment to the figure seems like a distant memory. Giant Women On New York feels like a call to the past, a point of reflection in a time of turmoil. There is work to be done and work to protect regarding women's rights. The works of these “giant women” provide us with opportunity to ruminate on the complexity of the female experience, and encourage introspection.

Lily Lady: You both head up influential NYC-based magazines, and you’re dating. Tell me about your relationship. Ripley, why are you squinting at me so skeptically?

Ripley Soprano: Sorry, I’m not squinting, it’s sunny.

LL: It looks really cloudy over there. But okay, let’s start with a softball. Why don’t you tell me about your magazines?

RS: Ladies first.

Penelope Dario: Petit Mort is a magazine and archive celebrating the intersection of art, sex work, culture and fashion. [The goal is] to showcase the cultural influence and wisdom of sex workers. To preserve our history. It's growing into other things, too, like a production company, because I want to break into other forms of media.

RS: Rock star over here.

PD: No, you're the rock star.

RS: Dirty is about documenting our lifestyle. It’s not unlike what Vice did. But we’re closer to the ground, with people who are actually engaged in the culture doing most of the writing. It's very design-forward. I have an incredible creative director and designer, Maia Raymer. We’re focused on New York City, and have a New York attitude in the voice. Both Petit Mort and Dirty’s writers are close to their subjects, which is different from what we've seen in other journalistic projects.

PS: Yeah, I can’t speak for Dirty, but reporting on marginalized spaces often feels like a National Geographic documentary about some exotic species. Instead, [our approach] is to actually have these exotic birds writing stories about themselves, talking about themselves to other people in the same spaces.

I try to straddle the line between things that are not too inside baseball, so that the general public can also enjoy them and feel like they're getting a voyeuristic experience without it being exploitative. There’s no, you know, what's your worst experience? or what's the craziest thing you've ever had to do? That feels like the National Geographic approach, no shade on National Geographic.

LL: The Petit Mort and National Geographic beef starts here.

RS: Or the collab starts here!

LL: Both of your magazines have been in print since 2021. What’s the key to longevity?

PD: I feel like I've been sitting in a casino for five years, and I just keep waiting to win big. Thankfully, I haven't lost the house in the process. Sometimes it feels like I've invested too much to stop. But [I tell myself], if you're working hard, and you're dedicated to the craft, things will happen. That faith is a huge part of it.

Also seeing people respond to [the magazine]...even if I’m not making a million dollars a year, even if it's just an archive, I think that's meaningful. It's a physical product that will outlive the blogs and the digital files. If I die tomorrow and all I ever did was create this physical archive of the sex workers I was able to report on, then that makes my life feel meaningful.

RS: Wow, that's such a good answer. Yeah. For me, longevity means evolving. The first issue of Dirty was so different. Now, I have this great team, between Maia’s design vision and Max Lakner [Dirty’s in-house photographer], it feels so cohesive. Now I feel like I can look at something and be like, Oh, that's Dirty. It definitely has a pretty strong sense of humor that I try to push for in all the editorial, the photography and some of the voice. But it's earnest. It's so much more earnest than I ever imagined it would be. For me, longevity is being open to evolution.

PD: We’ve been inspired by Dirty to be more funny, and not so serious.

RS: But I love serious.

LL: How important is being in print for each of you, as opposed to a primarily online presence?

PD: Making the [physical] magazine beautiful is important, because beauty softens the edges of learning and can bridge the cognitive dissonance between someone who has no respect for sex workers, no understanding of the industry, thinks it’s all sex trafficking you know, whatever. And then they open up this book because they think it's pretty, and they’re like, whoa.

[Graphic designer] Paul Glover did our redesign and was pushing for the matte. Paul said that for whatever reason, things that are glossy feel disposable. We’d been glossy until that point, and I hadn't really thought about it that way, but it makes sense. Like, there's something about it that feels like a catalog.

RS: This is where we diverge in an interesting way, Dirty started as a glossy, and around the time of the fourth issue, Maia had this idea to do a newsprint. It was hard for me to wrap my head around, since I felt attached to being a traditional glossy magazine. It took maybe two more issues before we did a newsprint, and I can't imagine going back.

One of the selling points of the newsprint is that it’s more disposable, and something that people can pass on or leave in a cafe. We can print more for less money, which is a selling point for advertisers.

The ideas in Dirty don't belong to anyone. I want these ideas to be proliferated. At Dirty, we believe that all good ideas come from the margins. Harm reduction and community care are big themes. The newsprint really holds the ethos of a street paper, of New York City papers.

PD: ‘What role does a magazine play?’ is something I've thought about a lot. Making it a beautiful item that you want to display in your home like an art book serves two purposes: it makes the physical product desirable, and it also allows me to raise the ticket price on the cover.

Coming up as a young sex worker, I thought, why don't we have our own Vogue? We are stars.

RS: But in terms of print media in general, there are so many underground magazines popping up and I'm not sure what their longevity is going to be, but it’s cool and inspiring. They all come in so many different shapes and sizes. Whether it's Dirty, Petit Mort, Byline, On The Rag…this is a movement. Nylon is going back into print, No Agency has a magazine, Vice is coming back. It seems like Playboy is going to do a print magazine, wonder where they got that idea….

There’s a print movement that's very much coming from young people, which is cool, and it's a response to COVID, isolation and overconsumption of digital media. I think it’s exciting.

PD: Because of the nature of the publishing industry, advertising money just isn't there anymore. So how do we survive in this landscape? That's something that Dirty and I share, since we came into this space at a time when magazines were dying. Niche magazines are kind of coming up, but these niche magazines come from companies that have tons of money that essentially can blow a marketing budget on a print product. But how do we exist, grow and survive in a landscape that's becoming more and more hostile to what we're doing?

RS: Wanting to be in print is also a response to FOSTA/SESTA, because we still face different types of payment processor discrimination.

PD: For both our magazines, [foregrounding] print definitely has to do with online censorship around sexuality. My threshold was always Vogue Italia. I was like, if Franca would publish it, I'll publish it. But I think ideological accessibility is important in terms of reducing stigma. People aren't going to be as compelled to read the stories I'm publishing, and to actually get into the psychology and philosophy of sex work, if they just open it up and see a porn magazine. I want them to open it up and see a fashion magazine. Or an art magazine.

That being said, my payment processor got shut down within the first three weeks of launching the shop, and it took two months to get it back running.

LL: What’s the business model sustaining both of your magazines?

PD: Listen, I’ve chosen to be a sex worker because if I'm gonna suck dick for money, I need to be sucking dick for money. In and out in an hour. I cannot suck corporate dick for endless hours over weeks of conversations for no money.

Maybe I haven't gotten to that point in my con-man journey of selling ads, because I don't even care about selling ads anymore. If a brand wants to collaborate and it makes sense, then great. But I'm much more interested in generating value as a publishing company, whether that means raising the price on the issues, or just being more creative about the product model.

I can't really say what the sustainable business model is right now. A lot of this is still funded directly by me. We have a fiscal sponsor that essentially allows us to get tax deductible donations from the public. Doing more fundraisers and having it be more socially supported is something I'm looking into as well. Profit isn't really the goal. Longevity and sustainability is the goal.

LL: What about at Dirty? Ripley’s over there, squinting, with a no free ideas look on his face.

RS: Nah, I mean, we dropped the cover price on the magazine. The idea is to subsidize it with advertisers and partnerships. We do a lot of events, too. The dream is to have a pretty hefty online shop with more merch so that it’s more likely that if someone buys a magazine, they'll also buy a $25 T-shirt. I want to get to the point in the next couple months where we're selling enough merch to keep us afloat on a monthly basis.

PD: We can't look at legacy publications and see what they're doing. That is a business model that doesn't even exist anymore for them. Flip through a Vogue and you’ll see…they don't even have any good advertisers anymore.

What could be really exciting about this new wave is how to figure out a new business model for these magazines.

LL: What magazines do you read, other than each other’s?

PD: Once in a while I'll go to a magazine shop and do a big haul. Just to see what people are doing and what's happening.

RS: I try to support the smaller magazines that are coming out when I can.

PD: I like Hommegirls, even though they did switch to glossy. But they're actually one of the most successful magazines right now. They were started by a fashion designer who also does a clothing collection for the brand.

RS: I like Hell Gate for New York focused news. It’s not print, it’s online. Their reporting is great, especially on the Eric Adams indictment. They’re super snarky. But I love old magazines. Old Playboys. Big Brother.

PD: Don't forget those copies of Project X I got you!

RS: Yes, Project X, which was Julie Jewels and Michael Alig’s magazine.

LL: So okay, we get the deal with the magazines. What's it like being in a relationship?

PD: It’s very sweet! We understand what each of us is dealing with, whether it’s production stress, printing stress, or talent stress, whatever it is. It's tough sometimes when we're both dealing with the same unknowns, because we don't necessarily have the answers for each other. But if you’re walking around in the dark, it's better to be holding someone's hand!

RS: I couldn't really say it better.

PD: We bounce ideas off each other, too. Even though Dirty and Petit Mort are so different, we share contacts and have a nice cross-pollinating space. I like to say Petit Mort for the girls and the dolls, and Dirty is for the boys.

*Ripley squints*

PD: Is there tea?

*Ripley squints harder*

PD: Okay, wow, you're bringing it there. You really want to spill the tea in this exclusive?

LL: Let’s hear it!

PD: So Dirty and Petit Mort started at the exact same time. And I had a crush on Ripley for a long time, before the magazines were even twinkles in our little eyes. I actually slid into Ripley's DM in maybe 2019, and got totally ghosted in a social media air ball!

A few months later, I'm about to announce Petit Mort, and a friend was like, wait, did you see that Ripley started this other magazine?

I was like wait, what? what the fuck is this?

I was a little bit of a hater for a minute. Dirty had a humorous sensibility that I struggled to tap into. I was struggling with my own self-censorship. Seeing what Dirty was doing, the risks they were willing to take…I was like, fuck that's so fucking cool.

Then we did the feature on you, Lily, when you guys were an item. You invited me to a Dirty party, which I went to, thinking, I guess I’ll find out what this shit is about. And Ripley was just so sweet. I had no idea that they were such a cutie-pie sweetheart. I thought they were just a hot fuck boy. And I thought, wow, lucky Lily lady over here.

A few months later, we got lunch and talked about running our magazines. And then [Lily & Ripley became best bros 4 life] and Ripley and I started hanging out every day. The rest is history. It’s funny how life works.

RS: The first time we got lunch, I remember leaving with this heavy feeling because I saw something reflected [in Penelope] that was very hard to receive at the time, because it felt like such a reflection of the difficulties [of running a magazine] that I really try not to show.

When I meet up with people, I try to be super positive about how it's going. And I am very positive, but to feel seen in this way, in terms of personal financial investment and sacrifice…it's really heavy. That's something we can relate on a deep level. That was a really moving part of getting to know each other.

LL: So sweet. What a well-rounded romp. Anything outstanding either of you want to convey?

RS: Petit Mort has a really awesome launch party that’s about to happen.

PD: Dirty is about to release what I think is their best issue yet.