Is Playboy Dead?

Now in their late 60s, my parents are still writing, navigating an increasingly unrecognizable media landscape. The remaining magazines they freelance for have smaller budgets, and book advances are typically a fraction of what they once were, making it harder to eke out a living as a full-time writer.

While Playboy remains an influential brand, its business model has changed too: in 2020, new CEO Ben Kohn announced that like so many other publications, the magazine would be shuttering its print editions and move entirely online. That same year, it became a public company, trading on the NASDAQ exchange as “PLBY.”

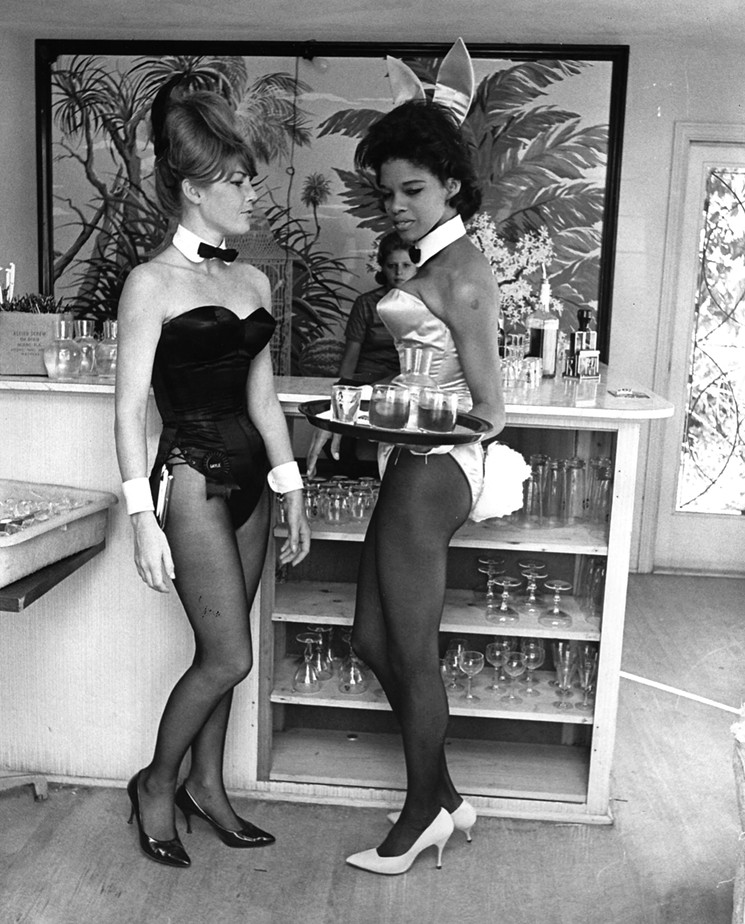

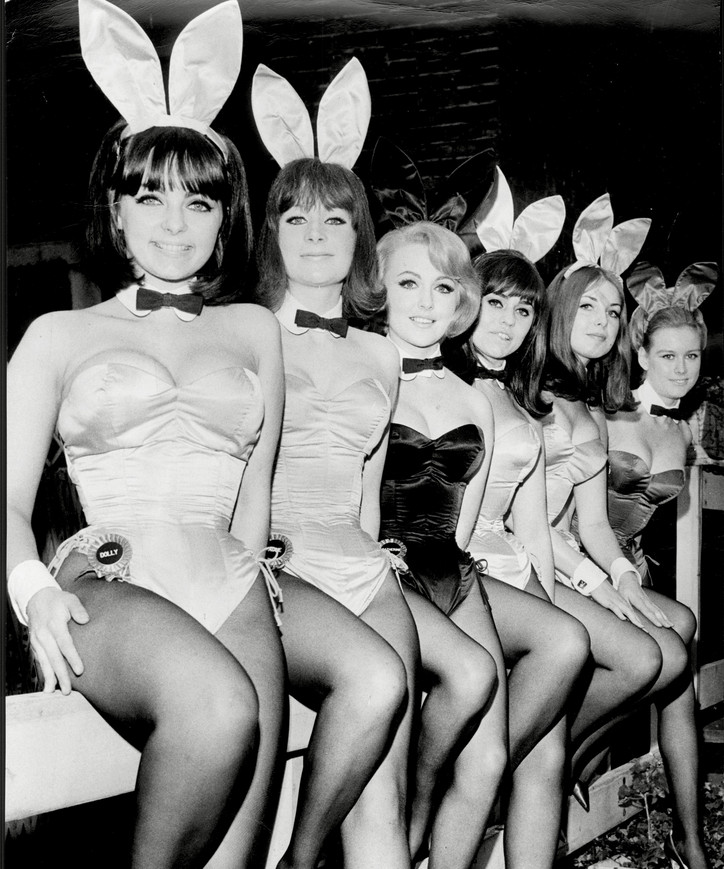

From its inception in 1953, Hugh Hefner steered Playboy into a brand that represented many different things to different people. Some saw it as a roadmap towards an aspirational lifestyle; to others it was an emblem of free speech and expression; to still others it represented all that was wrong with modern heterosexual culture and was a symbol of the exploitation of women under patriarchy.

However people felt about Playboy, its journalism was always central to its cultural relevance: where else could you get an in-depth interview with Martin Luther King Jr. (1965) or Palestinian political leader Yasser Arafat (1988) and read fiction by Joyce Carol Oates (1970), all alongside centerfolds starring the likes of Marilyn Monroe (1953), Anna Nicole Smith (1992), and Dita Von Teese (2002)?

To see a publication with such an extensive history shutter its print magazine in 2020 felt like a real loss.

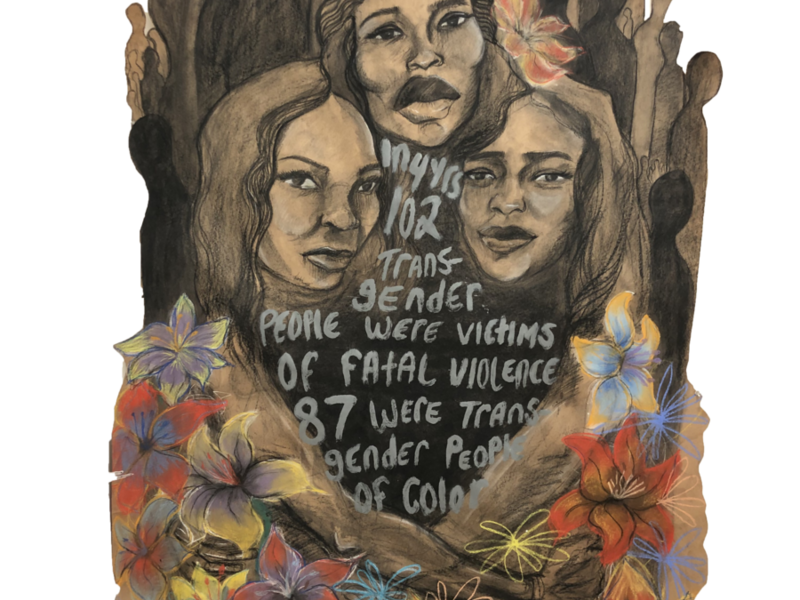

Since then, I’d been mulling over a new angle for Playboy. Is there a way to revive the magazine and be financially soluble? Can the magazine retain its core tenets while expanding inclusion along the axes of race and gender? I had some ideas for a path forward, so I set up a meeting earlier this year with Playboy CEO Ben Kohn, who I had been indirectly introduced to (more on that here).

Before our meeting, I had poured over all of Playboy’s publicly available financial records and had a working idea of where the company stood. At the restaurant in Brentwood, Kohn ordered a stack of pancakes and spent the hour regurgitating one liners I had heard him say in countless interviews. (“The brand is popular among the Gen Z crowd…”) But I knew that Playboy was in debt and that its stock was down. From personal experience, I knew that Gen Z didn’t really register the brand as "cool," and that the cheap clothes they license with PacSun weren’t anything I’d ever wear.

Ben — who has a background in private equity — didn’t seem to share in my enthusiasm about the value of resuscitating the magazine. Instead, he talked about the digital platform Playboy Club, which is comparable to a thoroughly unexceptional version of OnlyFans.

In the past, Kohn has stated that Playboy is “the one platform that has a true brand that stands behind it.” But the brand was built on journalism. Once you sacrifice that, what’s left?

‘I read Playboy for the articles’ was a common refrain to justify buying the magazine. The subtext is that a person must create an excuse in order to consume pornography. But the double movement of the phrase was always dependent on the veracity of the claim that one could reasonably read Playboy for the articles. Remove the journalism and fast forward to a cultural moment when pornography is more readily available and less taboo, and there’s really nothing special about a Playboy devoid of journalism.

Nothing came out of my meeting with Kohn, so I decided to stop pursuing the old Playboy and to write about it instead. I started at the very beginning, by calling my mother. I asked if she could send me some photos from her Playboy days, and maybe a few quotes about what her and my Dad think of the fate of the company.

My plan for the article at the time was simple: a couple paragraphs up top introducing my parents’ former roles at Playboy for context, launch into a discussion of the company at present, wrap up with a call to arms about saving journalism, etc. Over and out in a tight 2500 words. Almost immediately, I sensed hesitation. “Is office a real magazine, or is it online?” my mom asked.

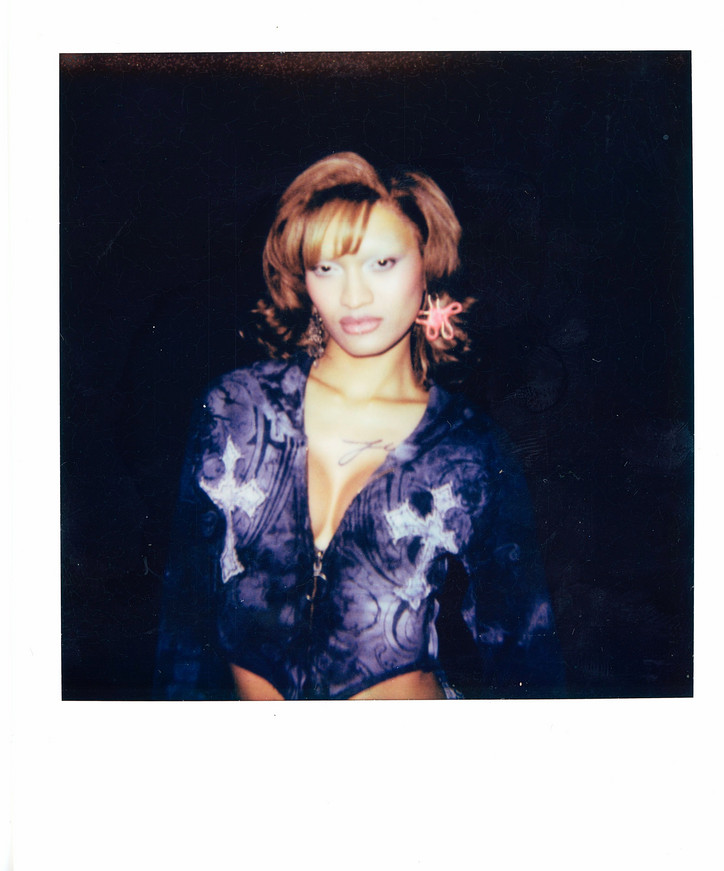

Her next question regarded the scope of my article. Would it reference my prior work as an escort? If so, she had a “hard line” about being involved. Given that I hadn’t started writing yet, I responded that I couldn’t guarantee what would be covered, but that escorting didn’t seem directly relevant to the piece and that it likely wouldn’t be discussed.

That didn’t seem to assuage her concern. The next day, I woke up to an email in which my parents declined to give a comment for the article. Their explicit reasoning was a preference for digital privacy in the age of social media. Implicitly, however, was the implication that print media is somehow more reputable than online publications, and that public association with ‘sex work’ made them uncomfortable.

I am so grateful to have two parents who love me deeply, and their approval means so much to me; I couldn’t help feeling this as rejection of me as both a writer and a person. It felt ironic that a part of my life regarding sexuality and labor was off-limits as a condition for their involvement, since I was ostensibly writing an article whose subject was their own former workplace at a men’s lifestyle magazine known for its centerfolds of nude and semi-nude models. Furthermore, the distinction between print and online media privacy felt arbitrary: my mother wrote a memoir about her life in 2005 (the year after Facebook debuted) in which I — as a toddler — am discussed. Why is digital space perceived as more exposed, when similar disclosures of personal information happen across both mediums?

Ultimately, Playboy’s failure to make an effective transition from print to digital journalism doesn’t indicate that good reporting doesn’t happen in online spaces. It just means that writers have to work harder to find them, to make them themselves, and to sometimes waste their time at meetings with corporate CEOs just to ultimately arrive at publication of their work elsewhere.

I believe in the transformative power of good writing. I believe in free sexual expression. For better or for worse, this is the state of Playboy in 2024, the state of journalism, and the state of my family.

Will it always be this way?

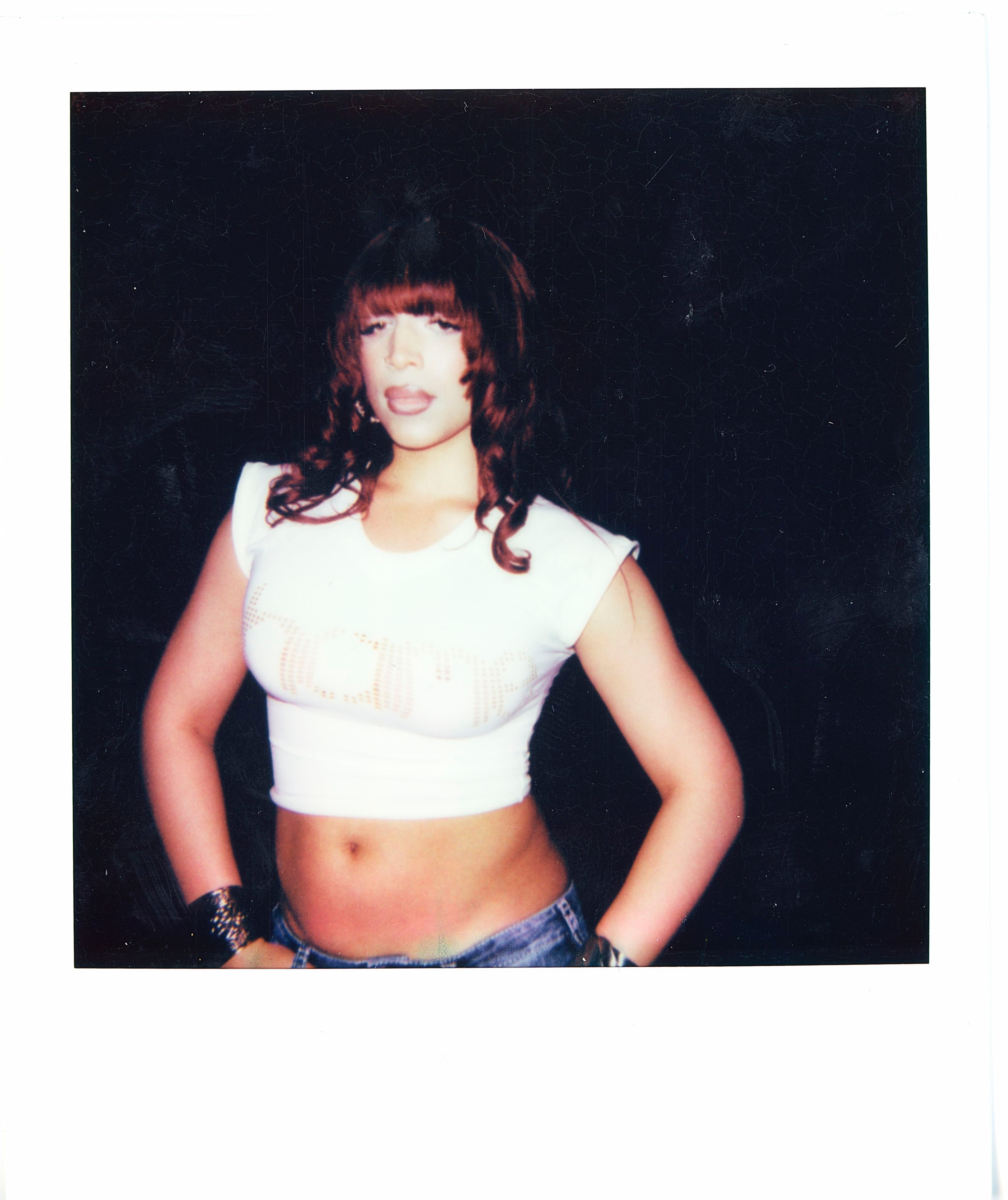

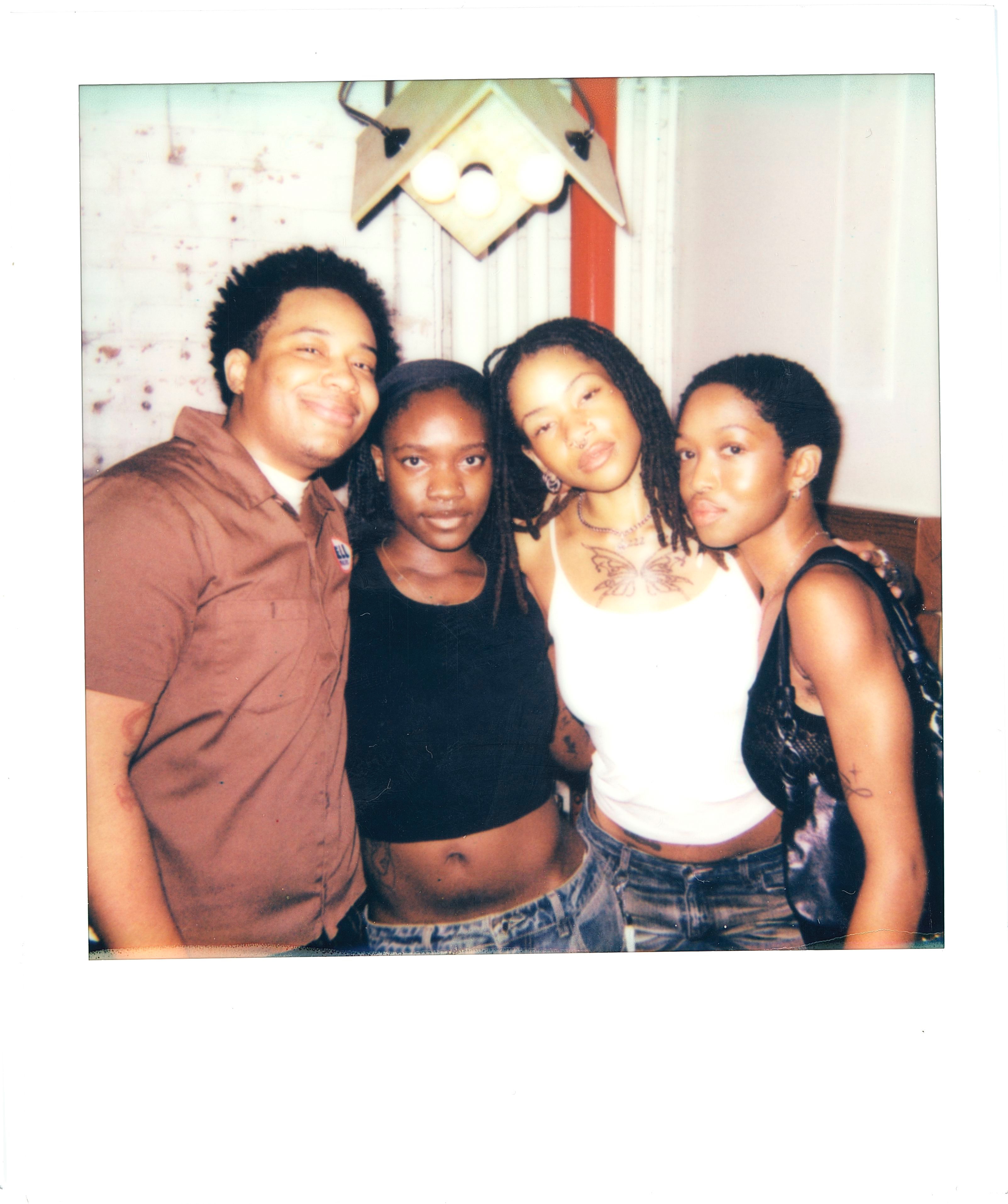

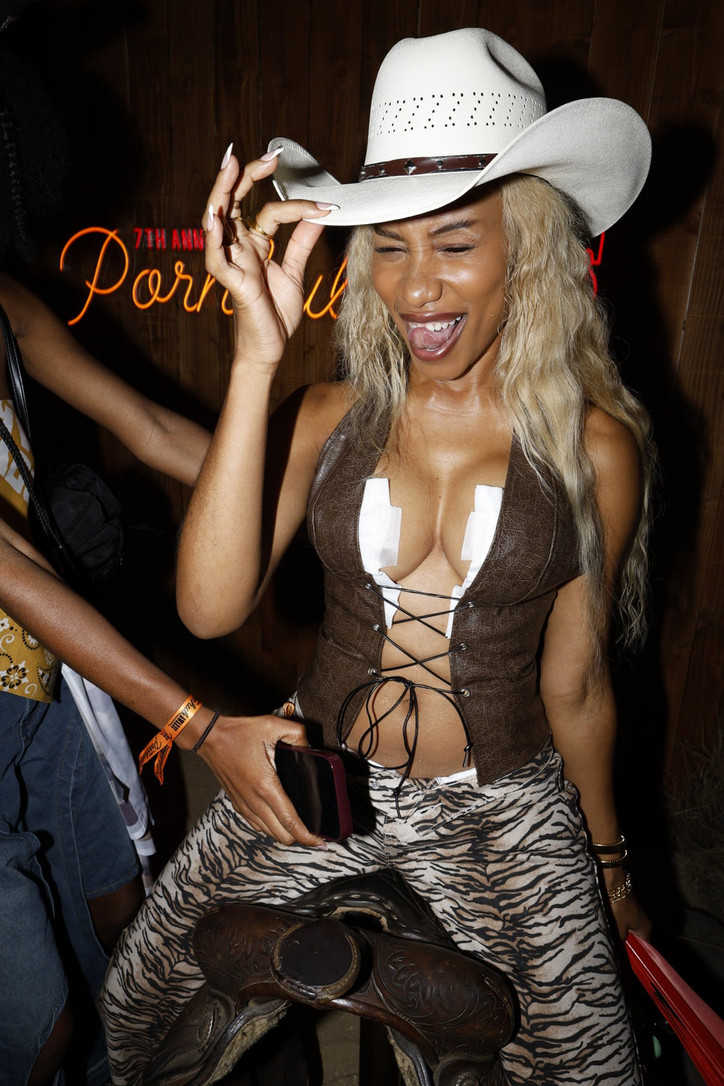

"a child of Playboy"

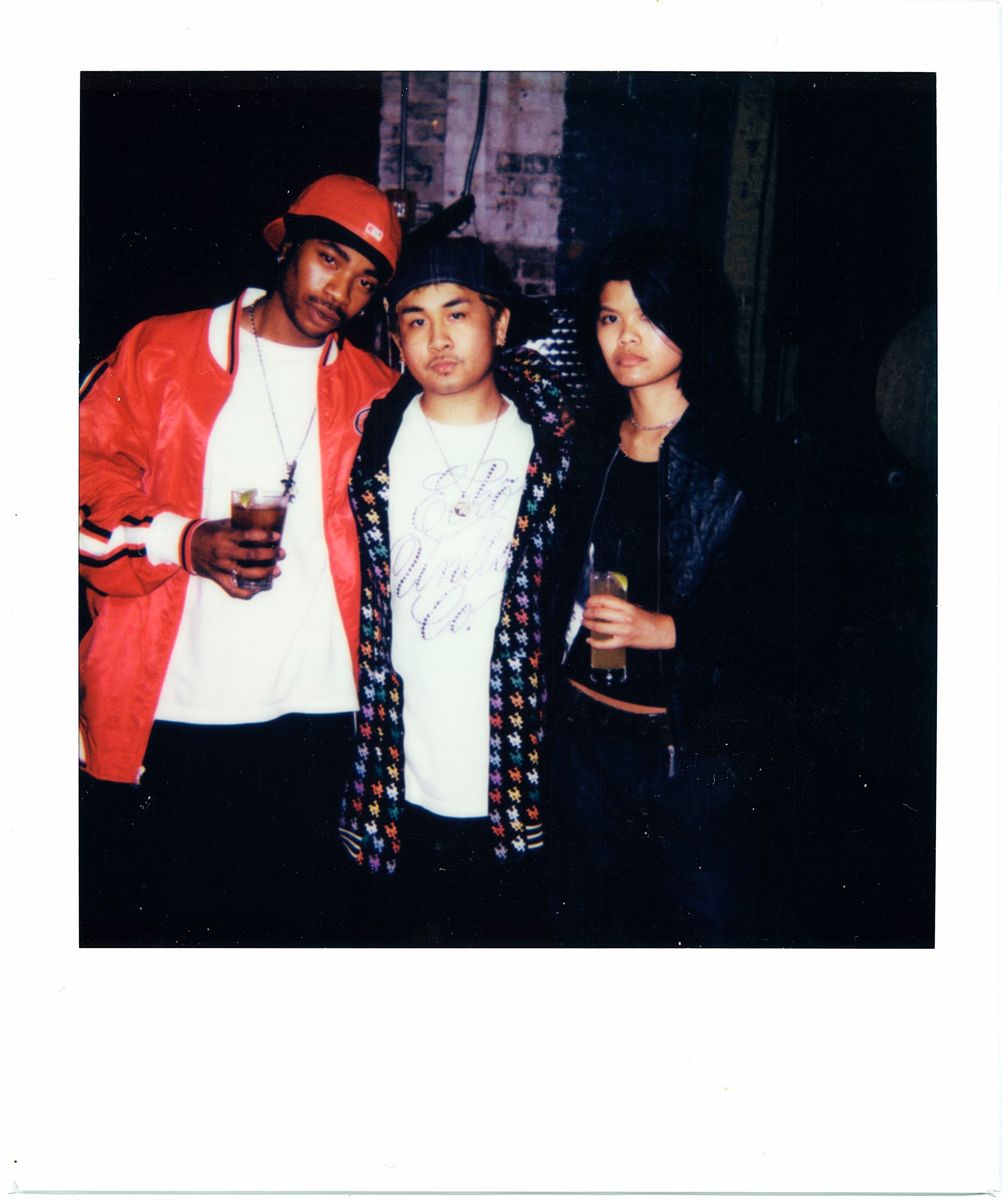

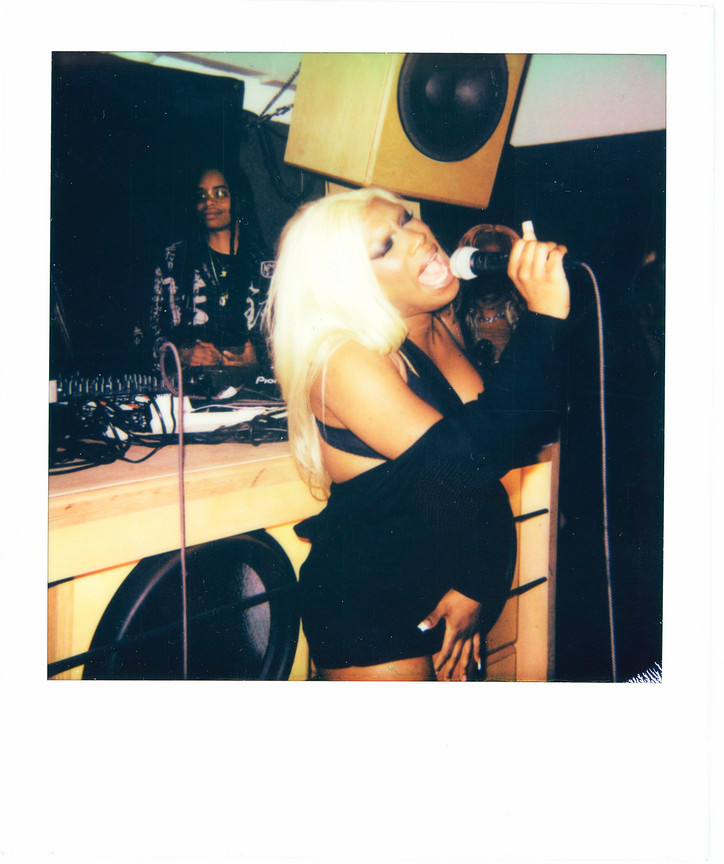

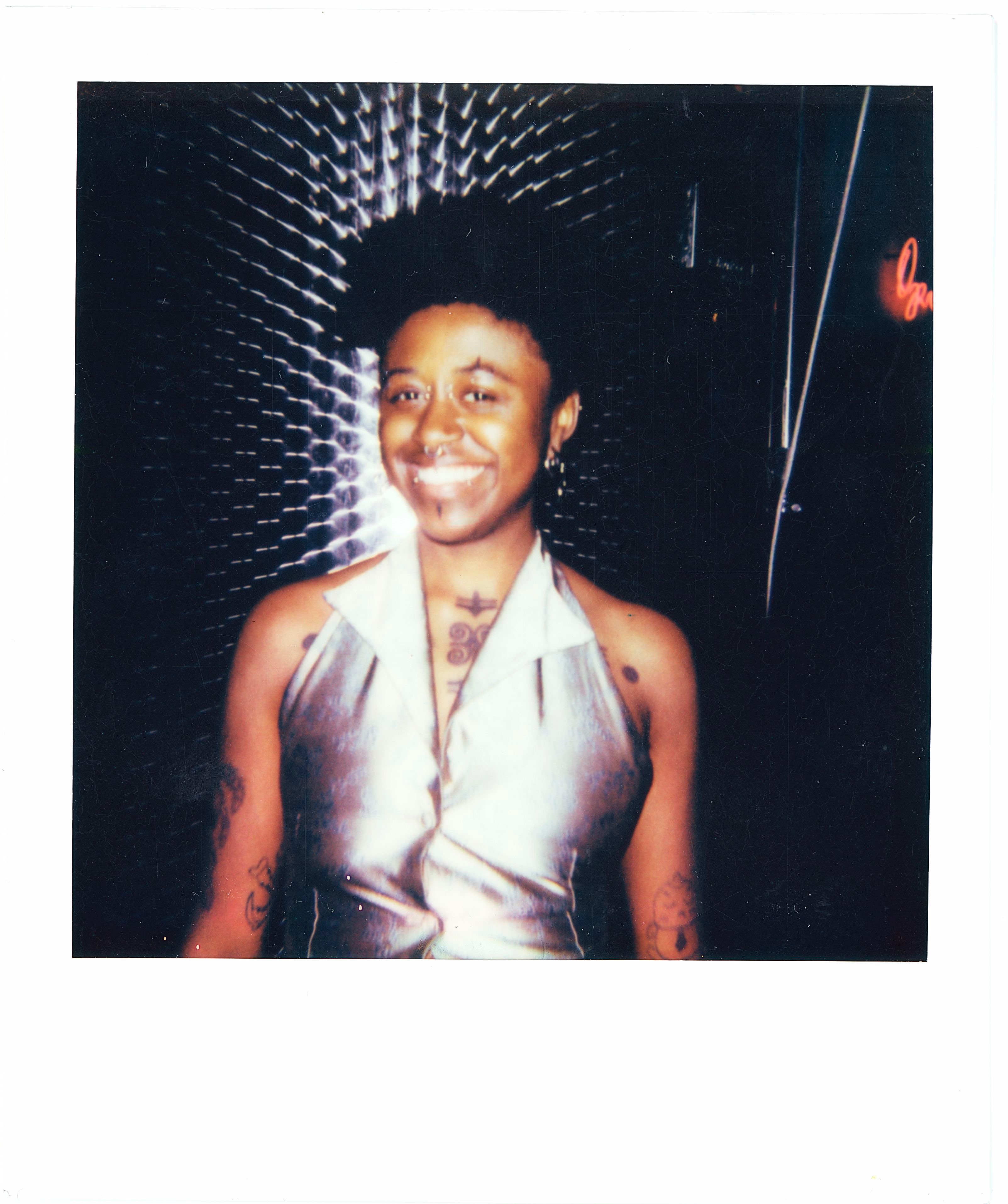

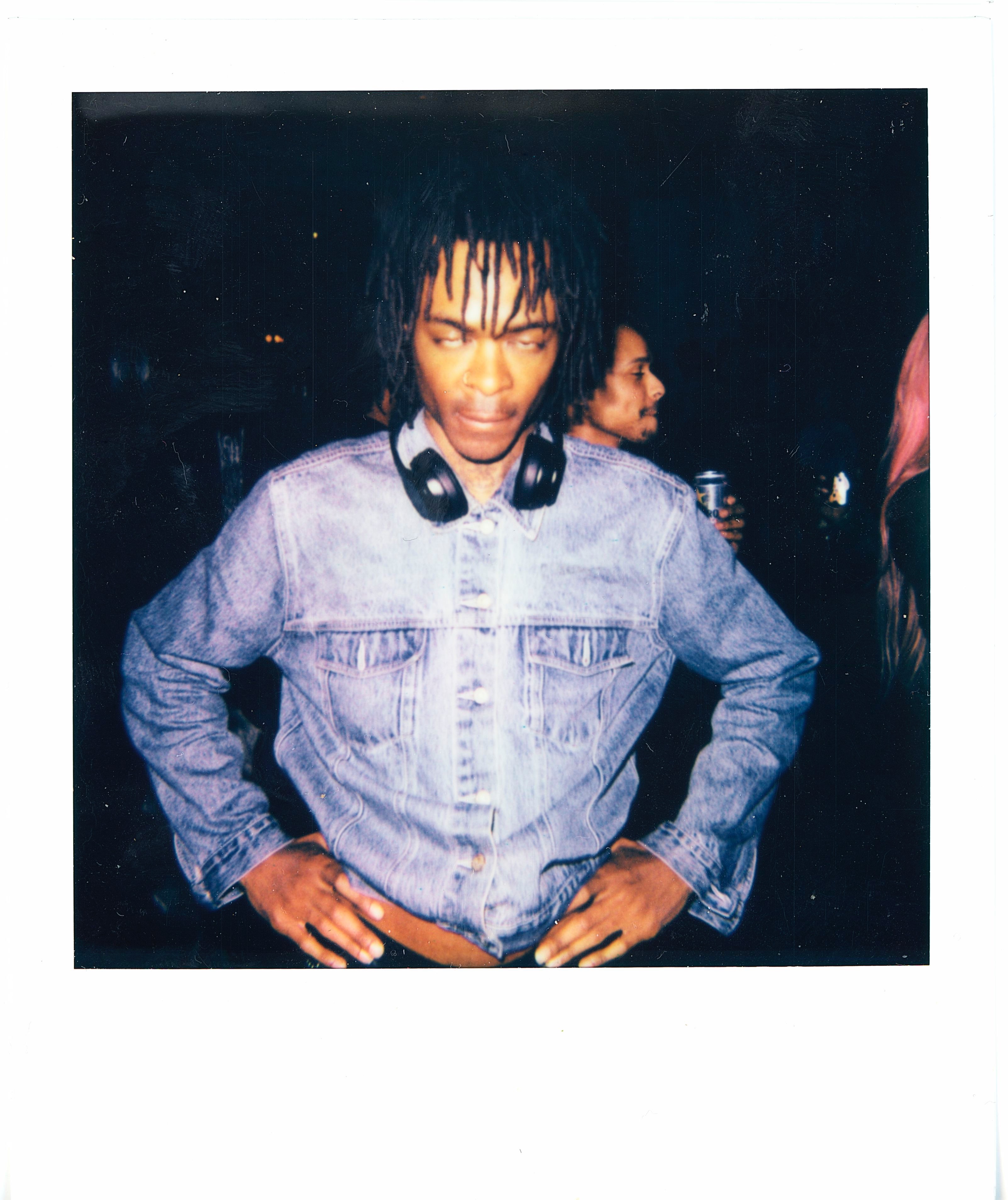

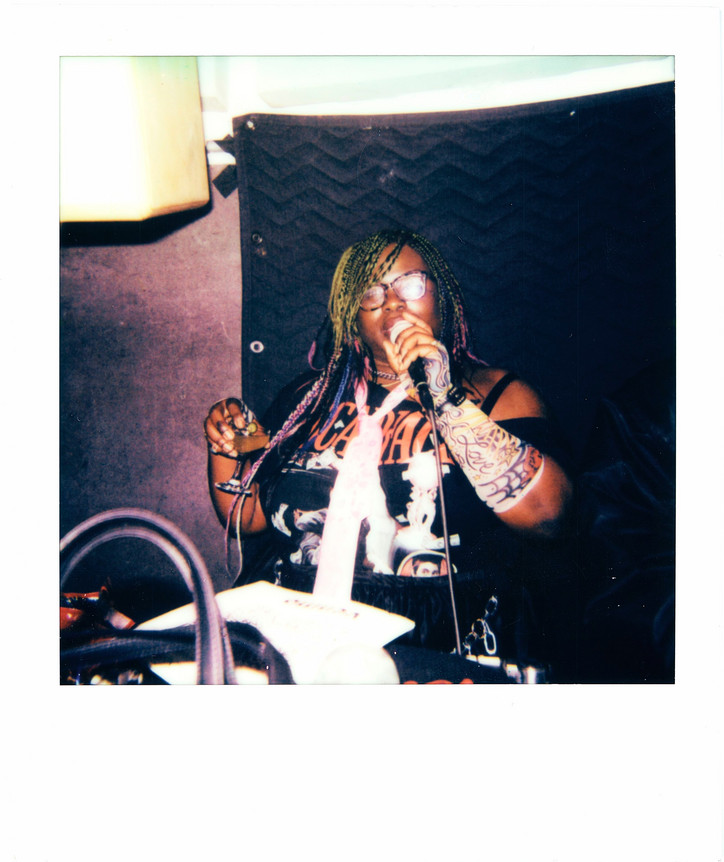

photos courtesy of the author