Fine Art Through the iPhone

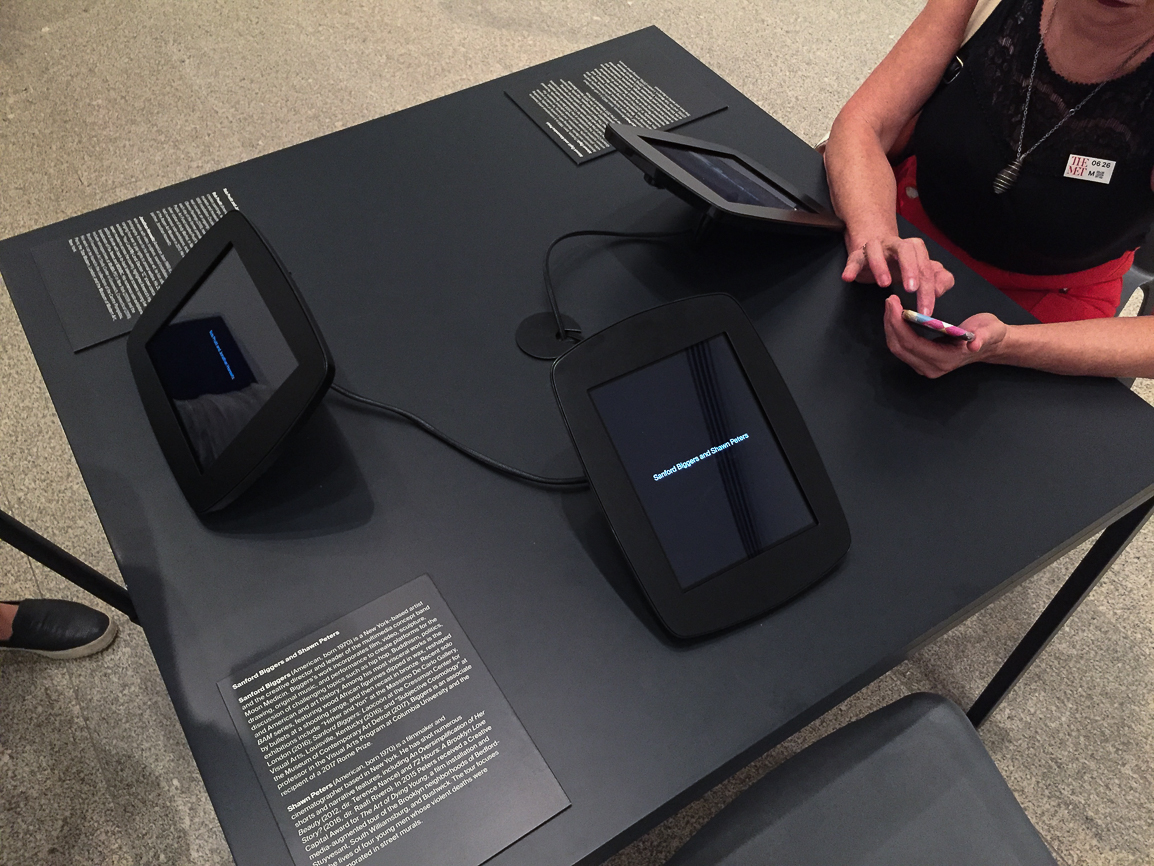

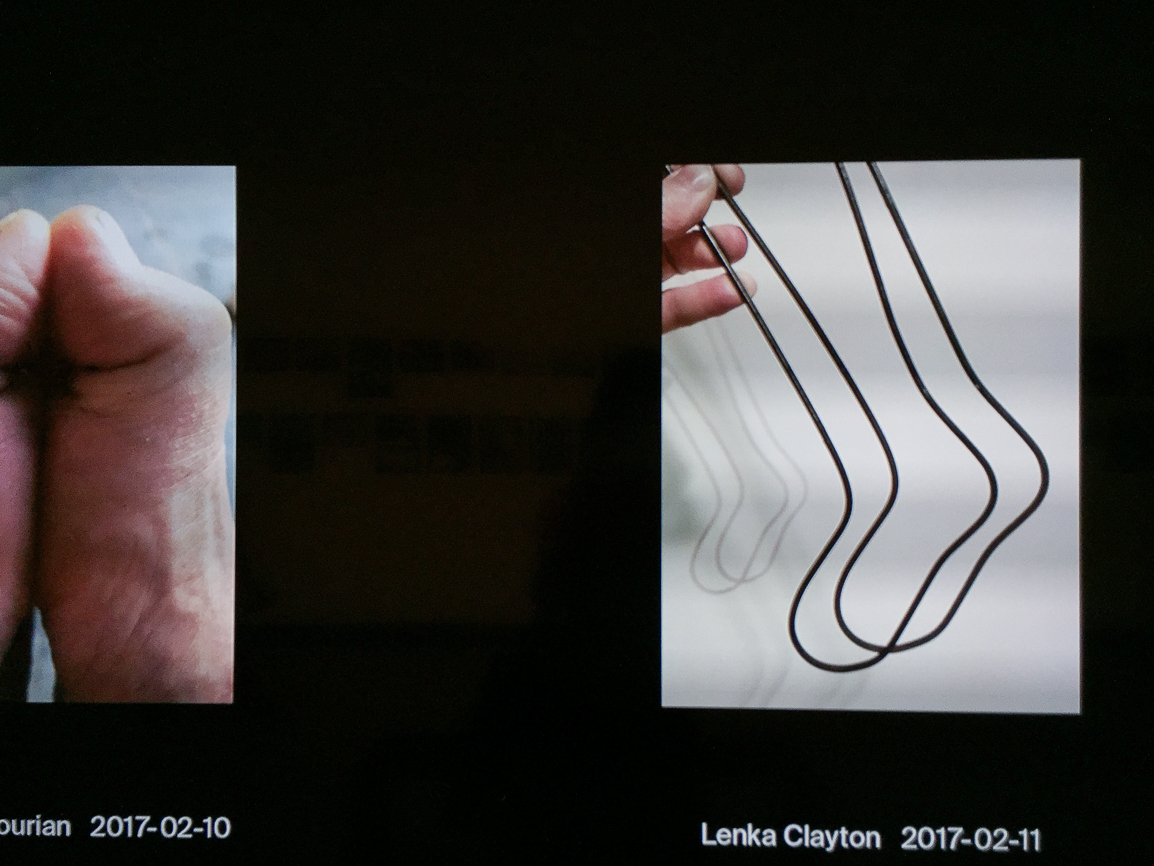

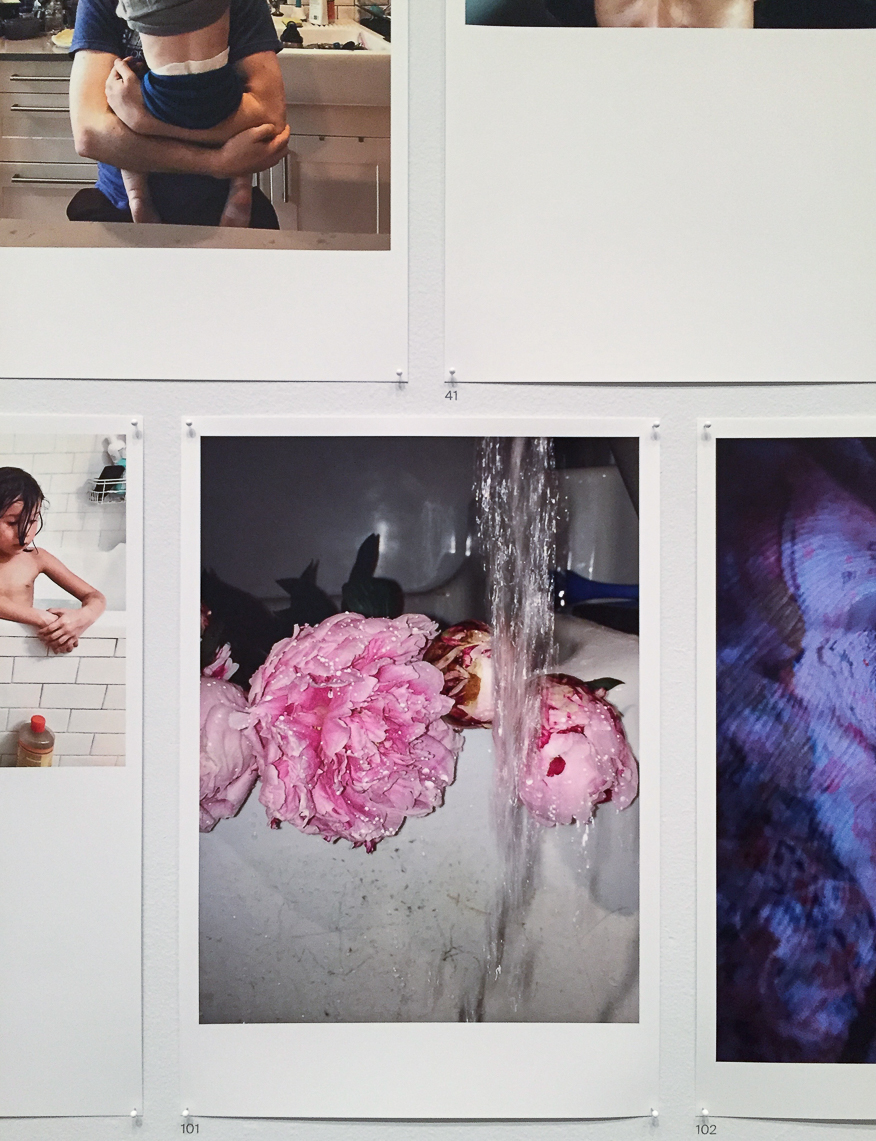

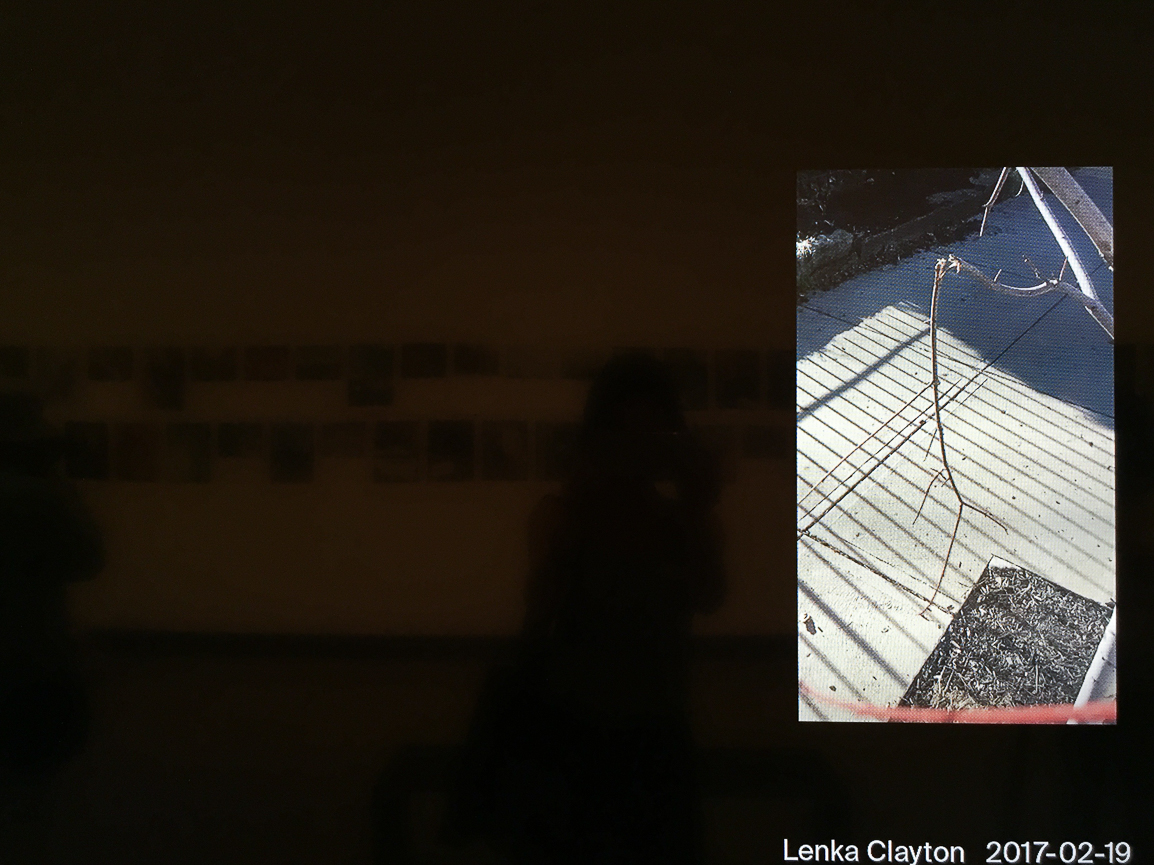

'Talking Pictures: Camera-Phone Conversations Between Artists' will be open through December 17th, 2017.

Stay informed on our latest news!

'Talking Pictures: Camera-Phone Conversations Between Artists' will be open through December 17th, 2017.

The journey begins with an inaugural performance in Ghent, NY at Art Omi, and then later continues as a rave in Bushwick, Brooklyn. As a meta-archival gesture, video footage from these events seamlessly integrates into a live video loop. Blending performance, sound, archival video, Black diasporic scholarship, and a series of talks, 3WI foregrounds the origins of techno within a Black music tradition. The stakes of this intervention are high given the ongoing historical erasure of techno — a genre originating from Black American subcultures within Detroit and Chicago. Both spectators and artist Dion McKenzie become intrinsic parts of a techno archive that is currently being divorced from its origins. Simultaneously, this erasure is perpetuated by a revisionist rewriting of techno history, positioning it as Western European, specifically German.

McKenzie traces a global history of techno, paralleling their personal journey from Jamaica to existing within a diaspora. In this interview, McKenzie delves deep into the ways in which their Jamaican upbringing profoundly influences their musical practice. Bridging the realms of academia and personal experience, McKenzie's autoethnographic project seamlessly weaves together techno scholarship with their own lived encounters. By merging the sonic and haptic elements within the initial Art Omi performance and addressing questions surrounding archivalship and erasure, Dion "TYGAPAW" McKenzie's 3WI dismantles the revisionist rewriting of techno's history.

Nameera Bajwa— Where/what/when was your first experience listening to techno?

My first experience listening to techno is a hard one to place. Because now that I know what actual techno is, I’ve probably heard it in my adolescence and had no clue what it was called but I knew it was something I wanted to be a part of. I knew it was music I would find my way to making in my future.

How would you trace the historical trajectory of techno?

When I discovered the true origins of techno, what we know as techno today, it was around 2012 via one of the few documentaries on YouTube that investigated a more accurate, and not whitewashed history. I was pleasantly surprised to learn that three young Black men from Detroit — Derrick May, Juan Atkins and Kevin Saunderson — referred to as the Bellevue Three, were the pioneers of techno. I was led to believe that techno is a European genre that originated in Germany. In this moment, this realization immediately occurred for me, granting me an opening, a connection, a truth. A truth where I could then place myself within a genre of music that previously felt exclusionary, because it was whitewashed. I now know that there is so much possibility for sonic exploration.

At the entrance to your show at Art Omi, there are two magnified passports plastered on the wall — one Jamaican and one American. So from the very start, we are made to think about our respective positionalities coming into the space. Is there a way in which your upbringing in Jamaica informs your relationship to music?

Coming from Jamaica where our music is percussion oriented, techno always made sense to me and felt very ancestral. My ancestors used drums and percussion to communicate and for ceremonial practices. Rhythm is innate. Techno’s primary elements are percussion, repetition, and rhythm established by a faster tempo. These elements are complementary to gathering and dancing instinctively. Jamaicans thrive in environments where we gather together, dance and connect physically and spiritually. Jamaicans have pioneered three genres that are now excessively commercialized: reggae, dancehall and hip hop. Oh, and let’s make that four — reggaeton.

Given the title 3WI, how do you place the progression of techno as a movement from North America to Europe in relation to your own diasporic experience migrating from Jamaica to the United States?

The Black people who are creators and artistic vessels for revolutionary art forms are erased from that very important history, mostly due to the extreme lack of resources and access. The way I see it, techno was extracted from Detroit and not given the opportunity to grow and develop in the U.S. because racism wouldn’t allow for revolutionary music made by Black people to thrive, so it was then exported to Europe where they saw the opportunity to co-opt it since it was something they had never heard or felt before, and the records were faceless at the time. With all of the resources and spaces available to them to build huge clubs, they could steadily disconnect the genre from its original birthplace. Tresor is the only music platform that I know of that supported the Black pioneers from the beginning.

I’ve had to leave Jamaica in order to be an artist. I was born in the 80s, so there was absolutely no possibility for me to be the artist that I am in that generation. Especially since I was assigned female at birth, and Jamaica is an aggressively patriarchal society. It was extremely difficult to navigate growing up there with all the sexist limitations projected onto me.

Basically, winning the opportunity to study abroad in NYC in 2002 changed the trajectory of my life. I applied for a student visa right after 9/11 so visas were cut significantly and I received one of the very few. Coming here and finding out Detroit was the birthplace of Techno, everything started to make sense in regards to why techno is a more harsh and aggressive sound. It’s a reflection of the city's history; the collapse and deterioration of the booming industrial city and the destabilization of the Black community. Techno was the response. I deeply connect with that in my own art practice, because I’ve felt the effects of colonial destabilization in the global south and I respond to the harshness of my immediate environment by translating that impact sonically through my musical compositions. We both look towards building worlds sonically that reflect our ancestral power and create new possibilities of being. To elevate and liberate those who care to know the truth.

The textual disclaimer within the piece about how you read techno as patterns perhaps due to your dyslexia is intriguing. How does the way you read music and see patterns inform the type of music you play?

It doesn’t inform the music I play as a DJ, but it does inform the music I make as a musician and producer. Take a 12 step hardware sequencer/drum machine, which are ideal musical instruments for me because I can instinctively program patterns, and take a more tactile approach to producing music. I also mention playing guitar in the textual disclaimer. The guitar is also very intuitive for me since the scales and chord progressions lay on the fretboard are patterns I can improvise with, which is similar to the way I interact with my drum machines and synth modules.

I noticed a third of the way through your performance that my foot had been tapping along to the beat of the techno, and over time, I would unconsciously start moving different parts of my body to the rhythm too. I looked around and noticed almost everybody else in the room doing the same, almost as if we were all itching to turn this into an actual rave. What did you think and/or the response from the audience during your performance was going to be?

The techno I make has a way of moving you without you being aware your body is compelled by the sounds to move. I incorporate rhythms that blend percussive patterns that you can hear in soca and dancehall and I blend it with the standard Detroit techno patterns. That’s a hard combination for the body to ignore. My sound is unique to me, because it comes from my lived experiences. I live for that involuntary response. I’m always pleased to learn that my music instinctually moves the body. That means I’m honoring my ancestors, I’m honoring where I came from and actively building the world in which I would like for Black queer and trans people to thrive. By creating spaces for us to gather and connect and support each other openly.

Could you expand on the spatial layout of the room? You, the DJ deck, the embedded text on the monitor on the right side of the room. And the speakers, the shelves and other dis/assembled furniture, as well as the green probing light on the left side. Considering that 3WI foregrounds sonic over sight, what was your thinking behind how the room would be spatially disordered?

For the opening performance I wanted a very bare space with the analog sound system on one side of the room and on the opposite side my techno podium sculpture which was activated by my live performance setup, which consisted of my modular synth (techno system) as my primary source of percussions, and other pieces of hardware, no CDJ in sight. This exhibition is all about the live performance of techno. The improvisation of techno. The Dj is not present. The artist is. And I wanted the room to spatially allow for sonic experimentation and for the sound to be the primary focus. The lighting played an important role in linking the performance to elements of the rave. Lighting is a key component of the rave. We are both in an improvisational conversation. I’m also a visual artist, and went to Parsons for my BFA, so the visual aspects of the exhibition are just as important to me as the sound. I edited both videos that are the main focus of the exhibition and I designed the podium that’s the techno altar sculpture that my gear was on during the performance, which is also in the exhibition. So the opening performance was only a component of the exhibition.

Considering the Art Omi performance video footage is integrated into the exhibit, what do you make of the transition of the audience’s role from a position of passive spectators to actors / archivists? Would you consider this a meta-archival move? As a means of visually representing the historical archive of techno, does the video footage of the performance become a medium through which you as artist and we as spectators become part of the archive itself?

That’s a very valid interpretation of having the performance as part of the exhibition. That feels like a natural progression of this exhibition for me, the artist and audience as a techno archive. When it comes to techno, the audience/raver and the artist have a close relationship. I am creating an opportunity for an exploration of sound in the context of space and environment, with techno as my framework. The two performances on display in the exhibition take place at separate times and separate places. One in a Brooklyn warehouse in Bushwick, the other at the Newmark Gallery at Art Omi. One a DIY space, an environment that is very comfortable for me, in those spaces I created TYGAPAW, to explore what was sonically possible in the underground of Brooklyn. A blank canvas to dive head first into, a curiosity for heart pounding bpms and heavy hitting kick drums I found my way to Techno organically in these spaces. The other video in an art institution in Ghent NY, where the performance is observed but not limited to observation. I leave enough space for the audience to decide how they would like to participate in the performance, but requiring that they remain behind an invisible line that creates physical space between myself and the audience. While the only thing that separated myself and the ravers in the bushwick performance was the table that housed my modular synth and hardware setup. The two videos are live performances of me in very different environments. Exploring the possibilities of how techno operates when it is taken out of the spatial context of the rave. Is it’s sonic impact diminished outside of the space it is intended for. That’s the ongoing conversation.

3WI is on view at ART OMI through February 18, 2024.

Emma Louise Rixhon— So, tell me about the title of the show.

Alexis Loisel-Montambaux— They are the lyrics from a song by Johan Papaconstantino, who sings in Greek and French, meaning, “I cried at the end of a manga”. We chose it because it captures the profound empathies that we feel in relation to the fictions that surround us.

Felicien Grand d’Esnon— The English translation, however, doesn’t capture the expanded space and temporalities in the French, meaning you are crying during, at, or even about the narrative you are envisioning.

ALM— It frames the exhibition, showing how we sometimes direct exaggerated emotions towards fictions, especially in the context of what is happening currently in the world around us that is much more severe. But at the same time, these fictional worlds enable us to have necessary introspections and create interior worlds where we can incorporate characters as extensions of ourselves. These artworks are materialisations of where our imagined lives and our lived experience can meet.

FGE— We are looking at how universes based on manga, anime, and digital worlds create our intimate universes as we are coming of age, and how these then accompany us later into our adult lives and shape the ways in which we engage with culture and other human beings. We want to break the way in which manga is still often “othered” in exhibitions and show how it has become integrated into the visual cultures of so many contemporary artists. We are exhibiting art that shows how this aesthetic and intellectual media has been digested by so many artists from the world over.

Are you looking to canonise manga, then? Rather than having exhibitions only about it, showing art that uses it as a reference point?

ALM— Yes, we are looking to showcase contemporary art that uses manga as a prism through which to represent and reflect on other themes.

Eliza Douglas’ art explores the porosity between music, art, and fashion, that they feed into each other without clear distinctions. They collect merch from ubiquitous characters, such as Sailor Moon, and transforms iPhone photographs of crinkled t-shirts into hyperrealist oil paintings. Their process reflects on the creation of value in fashion, assigning assistants to paint them and then adding their signature as a monetisation of the work, like designers’ names embellishing garments. They also explore the endlessness of reproducibility, being paintings of photographs of garments featuring digitised images of televised drawings.

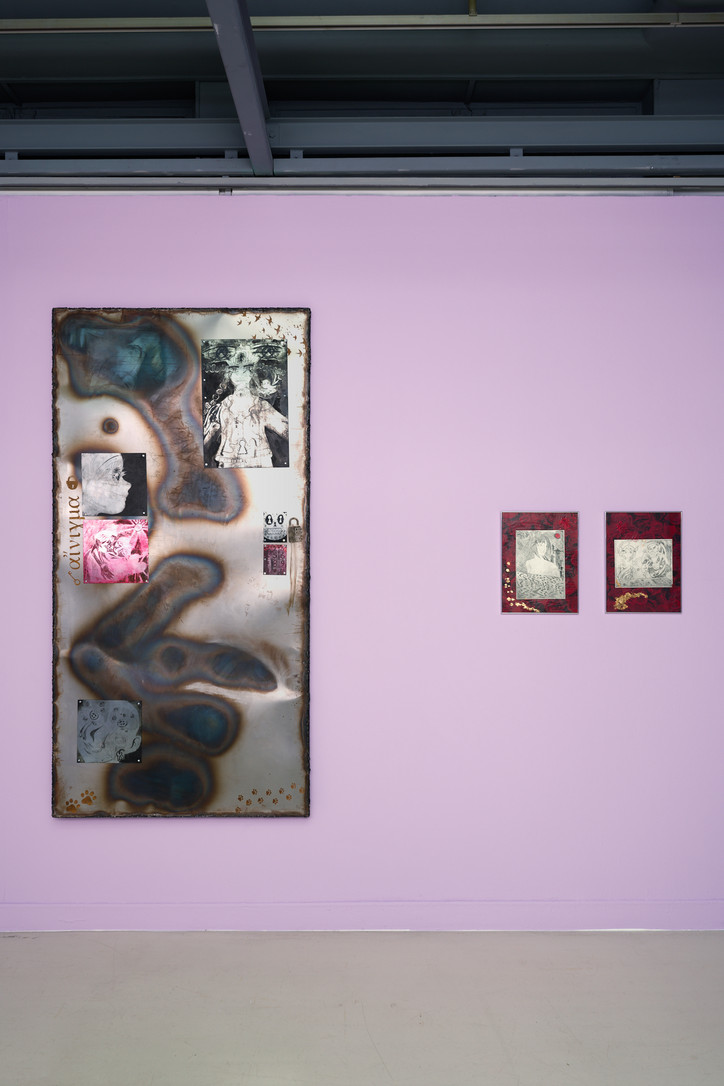

FGE— Gaia Vincensini’s work is in direct relationship to her family, particularly her grandmother’s practices. Using production methods which are haptic, such as zinc engravings, she materialises a knowledge exchange between generations. She incorporates representations of feelings, which you can uncover but not understand, through visual representations of manga and anime, with the materiality of collaboration between friends and family. Her drawings are her own creations, they are not existing characters, but more like guardian angels.

Gaia Vincensini, Matrice_III, 2021, Plaques de zinc gravées à l’eau forte et marquées à l’huile, 200 × 100 × 3,5 cm, Courtoisie de l’artiste et Gaudel de Stampa, Paris; Créature de la rade 1, 2018, Gravure sur cuivre, impression, feuille d’or, 40 × 30,5 cm, Courtoisie de l’artiste et Gaudel de Stampa, Paris; Créature de la rade 2, 2018, Gravure sur cuivre, impression, feuille d’or, 40 × 30,5 cm, Courtoisie de l’artiste et Gaudel de Stampa, Paris.

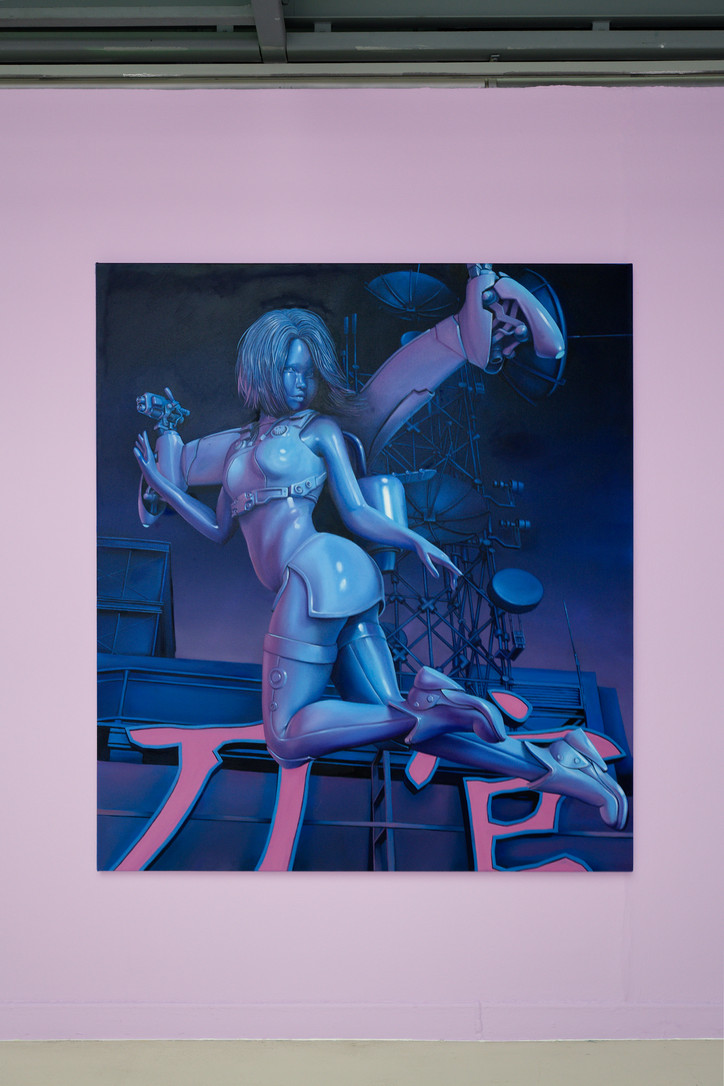

Emma Stern, Jody (packin’), 2023, Huile sur toile, 182 × 164 cm, Courtoisie de l’artiste et New Galerie, Paris.

They feel like guardian angels, but also saints or deities watching over us that are a blend of mysticism from our own imagination and our culture’s. They feel protective over us.

FGE— This aligns with Neïla Czermak Ichti’s Bic pen works, which portray friends but also manga characters. One of her pieces showing is of Guts from Berserk, and he is invoked as a sort of deity. It’s not dissimilar from seeing representations of saints in churches or illuminated texts from the Middle Ages. She includes herself in the image, fusing herself into new mythologies, looking at how we construct ourselves in relation to contemporary myths and deities.

ALM— It also ties into Ram Han’s objects inspired by 90s-2000s visual culture to represent the world of imagination that they created within her. Her images don’t shy away from how these images were less realistic than current video games are. They’re reminiscent of little animals like Tamagotchi, not alive in a biological sense but requiring daily domestic care. They also straddle the idea of cute and monstrous, they embody deities who can choose to protect you or punish you, creatures who could feature in a contemporary Hieronymus Bosch.

A lot of these pieces seem overwhelmingly huge, truly monumental canvases.

ALM— This is just chapter one of the show. There will be a chapter two with a different selection of artworks in November, in a castle complete with chandeliers. We are bringing work in that would usually be considered popular art in these spaces. So, the size of the canvases, as well as the typology of other works, is a bridge between the stereotypically aristocratic sphere of art and the dimension-expanding themes of these by evoking artworks that would traditionally be shown. The experience of the second exhibition will be temporarily inhabiting the life of an avatar who lives in the castle of Aubenas. We want to blur the boundaries between realities and fictions, as well as history.

Edward Said wrote in his memoir Out of Place that “all families invent their parents and children, give each of them a story, character, fate, and even a language.” He, of course, was speaking in the context of a particular identity formulation that you both share: the experience of the Palestinian diaspora. Could you tell me a bit about what was invented for you, both by your family themselves, and the diaspora as a kind of family? And in that vein, what do you hope to invent yourself?

What I've learned from my dad, and the stories he’s shared with me, is that as an immigrant you have to carve a space for yourself that doesn’t already exist. I’ve taken that into consideration for myself as an artist. If you’re conveniently plugging yourself into something that's readily available then you aren’t really challenging yourself. Having to carve a space for yourself is a ubiquitous experience for many immigrants, not just Palestinians in the Diaspora. I think we have that in common with a lot of different groups as well.

It can often feel, when I speak to Palestinian artists and intellectuals in this country, that there’s a tension between Palestine as a kind of imaginary, or a symbol, and Palestine as it exists. How do you, and by extension, your work, navigate this relationship?

I’m always encouraging Palestinians in diaspora to visit the motherland if they've never been or haven’t re-visited in the last five years. Of course, this is easier said than done. Many Palestinians aren’t as fortunate as I am, because they’ve been exiled from ever being able to return. But I encourage this because there is a kind of fantasy-land that the diaspora projects onto contemporary Palestine. Even that term “contemporary palestine” is an oxymoron unto itself. But in my work I try to depict the actuality of the kitsch, the Abrahamic, the colloquial, and the agriculture that all exist in one place. The bizarreness of all those elements can be overstimulating: I often feel like it is a type of disney-land after all.

That makes total sense.

Yeah, it’s bizarre: you walk out of the church of nativity and you see several store fronts that have been there for ages, and they have this huge coca-cola banner because they’re being sponsored by coca-cola.

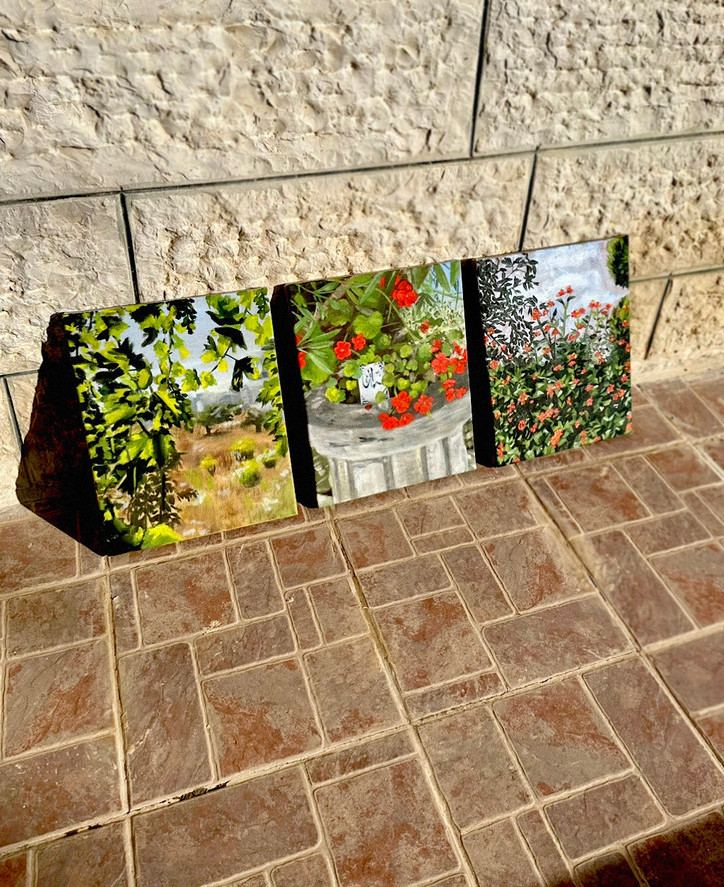

Untitled, 2023.

Right, and I think “Disneyland” is an interesting descriptor given the corporate element. I know your work in the past has been invested in the ways in which corporations and globalization interact with and have affected pre-colonial culture.

A lot of the disney stories themselves were derived from Abrahamic faith tales.

What was it like moving between St. Louis and The West Bank as a kid? Did you experience it more as a kind of liminalism (an in between-ness) or more of a full immersion in both, or neither?

Before the age of cell phones and the internet I spent a lot of time outside and exploring the land. I was able to walk everywhere in the area I grew up in America— I didn’t have a lot of constraints like residential streets leading to a main street. I’d spend a lot of time hiking. That isn’t the case in The West Bank. You can only walk in the confines of your village. That’s not to say that there’s a gate around the village, but you just know the boundaries. If you strayed too far, you’d be trespassing into a neighboring settlement which would cost you your life. Those types of severities were so normalized I didn’t understand the concept of apartheid as a kid. You know those types of stories your parents would share with you, like “if you do this or don’t do this the boogeyman is gonna come after you?” It felt like that: if you go too far, you’re going to be shot by the boogeyman, a.k.a. a settler. That was my understanding of what apartheid, that difference, was as a kid.

Can you explain what you were trying to express with this piece “Noman’s Land” from your series At Home in Your New Home? I find it quite powerful.

I feel like every American artist should take the opportunity to reinterpret the American flag through the lens of their own relationship to it. I made the piece in 2019, and it was my way of grappling with the anti-arab racism and islamophobia being propagated in America by the Trump administration with the “Muslim ban” that he issued. I remember when I got the work framed, the employee was so offended by the stars being opted out for the Keffiyeh and the shades of Arab complexion for the red stripes. And I asked: how do you identify with a land or a place without its stifling bureaucracy? We give meaning and purpose to a state, and if we rely on it being the other way around, we’ve become complicit with limitation and indoctrination.

Noman's Land, 2019.

That’s profound. And obviously the piece has taken on more urgency given the events of the last few months. Sadly it doesn’t surprise me that the employee was offended, but it’s good that you challenged them.

Yeah. I could tell that she wanted to make an excuse in order to attempt to not service it, like give a technical reason it couldn’t be done, claiming that it was a “loose object.” I was like, “why don’t you just make the frame for me and I'll keep the piece and mount it myself.” So they couldn’t legally say that they refused to service me [laughs].

How do you feel about the radical shift in discourse following October 7th? I'm curious particularly how you as an artist, a mode of being so intrinsically tied to expression, feel about the turbulent mass of attention being brought to Palestine and its history. Does the pressure to speak out feel stronger than the pressure not to speak out? Have you found the pressure to align yourself with any particular identity or political movement oppressive?

It gives me hope for my people and for humanity that there’s unwavering support for Palestinians that hasn’t been present before because people are becoming aware. I’ve taken it upon myself to be assigned with two tasks along the way. One is “attraction, not promotion,” and the second is to be completely authentic in the journey of doing so. When I learned that people became gravitated to supporting our liberation through the humanization of my people, I realized I just have to continue story-telling through art-making and my experiences. I think that things like that are only oppressive if you listen to people’s criticism along the way. Many people have been trying to police the ways in which I highlight humanitarian and societal issues. My response is to remind others that they have their own ability to represent the issues that they want to, and that everyone has a role in this. The radical shift in discourse hasn’t been limited to just Palestine, now we’re talking about collective liberation that calls for justice to be brought to the people of Congo, Sudan, Syria, Iran, and marginalized communities across America. I think that’s the most radical shift in discourse since October 7th.

Untitled, 2023.

I saw that you’ve been bringing your paintings to protests, is this a common practice for you? I’m curious if you could delve into what that relationship to art in a political/public space is like for you, as opposed to a fine art space like a gallery.

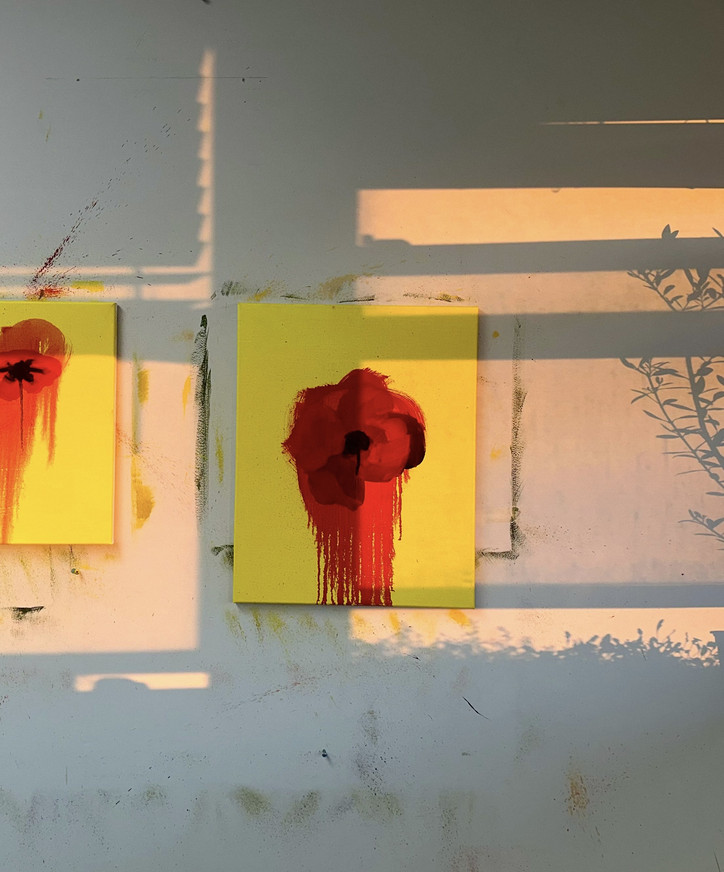

I’ve been going to protests since I was in a stroller, and I had given up on demonstrating for years until this most recent uprising. I was in my studio, painting, feeling hopeless and contemplating if I even wanted to tap into the first protest after October 7th. I was painting a poppy flower when my home-girl hit me up and asked me to join her at the demonstration. So I just took the canvas off the wall and held it up at the march. I’m very anti-flags and I reject nationalism, so this forced me to think of more ways to approach identity free of state-politics. After I’d gotten resignations from galleries who didn’t want anything to do with Palestine or a Palestinian artist, my purpose shifted towards activism. I didn’t want to compromise being an artist just because I lost opportunities or because I'm in immense grief, so I've been considering how to make protest a performance art. After all, M.L.K. was the greatest performance artist of the 20th century.

Totally. There is an art to protest. And I think your praxis speaks to a lot of the criticism of the fine-art world: the notion of art as purely decorative, of a piece as an ornament.

It’s also an institutional thing. Paintings are often hung up on a white wall, attempting to be pristine. There’s something grittier about taking it outside on a walk as the piece collects outside contaminants that otherwise wouldn’t appear on it. I’ve been working on these poppy paintings, which have now become a series, because the poppy is the national flower of Palestine. Every protest, demonstration, or activism meeting that I take part in, I’ll take a new painting and hold it up in place of a sign or something with words. I’m considering how the environment I'm in is a kind of installation: it’s giving context to what I stand for. And I want to incorporate the poppy to be a signature element in order to reference our Palestinian landscape. What I imagine for this ongoing series is that for the next spring protest I’ll distribute the collection of poppy paintings that I've created along the way to protestors so that we hold it up and become a field of poppies during the spring equinox.

Wow. That’s beautiful, I didn’t realize you had that meta-intention. That’s a powerful image. On the topic of expression, what does it mean to you to make art in the midst of violence, especially an on-going violence like that which has existed in Palestine for so long? This brings to mind the Palestinian poet Marwan Makhoul’s poem which made the rounds on social media recently:

"In order for me to write poetry that isn't political,

I must listen to the birds

and in order to hear the birds

the warplanes must be silent"

I know that you went to the West Bank to continue your practice last summer, and also have recently made another trip there. I’m curious how these experiences may have changed your perspective on this topic, if they have at all. This also ties into my previous question about the cacophony of chaos that is public discourse at the moment, which is its own “warplane.”

Yeah. That was one of the first poems I saw circulated. I think a lot of artists that work in the realm of politics and identity resonated with it. Do you remember the combat field musicians that they taught us about in history class? I’m starting to realize that my favorite place to be an artist is where it’s most dangerous to be an artist. I feel like I've been assigned a new role amidst the chaos that’s beyond my control, the role of art-journalist: making art in real-time, touching physically whatever’s on the ground, disdaining the pillars of smoke off in the distance. I think this most recent experience made the notion of art-journalism really immediate and urgent. It felt really free too. There was also a lot of censorship I had to be weary about. But when it feels like you have nothing to lose, you’re going to be most vulnerable and create really good art.

Untitled, 2023.

My last question has to do with the state of the art-world more directly. What kind of relationship to the art-world bureaucracy have you had in the past, and has it shifted in the last few months, if at all? If it has, how has this relationship changed?

What’s been going on in the last few months is not a new issue that I personally have been dealing with in the art world. The bureaucracy, censorship, economic, social, and environmental injustices are all interconnected. I see this issue as a moral litmus test that has bled into the art-world, which should be the place to hold this discourse. So much of the art-world is like “we don’t want to be involved in politics.” But the ongoing art-movement in the last decade has been about identity politics, so people have been picking and choosing which identities and stories are palatable and worthy of being drawn from. And has that changed as of now? It’s still definitely in effect, but I hope that this isn’t swept under the rug. I know a lot of artists, the real heads out there, aren’t going to be ok with it being swept under the rug. Because they understand how hypocritical it would be considering their practices, which involve so much political identity discourse.

Right. So you feel like it’s really only a matter of time, at this point, before these things change.

Yeah. Every week now a new story appears about another art-group being canceled or resigning from some sort of show. And there’s so many stories that haven’t been covered of decisions of artists to not work with a gallery as a result of it’s hypocritical stance on Palestine or censoring Palestinian artists, even if those artists haven’t made a public statement about it. I think what’s really beautiful about what’s going on is the solidarity network that a lot of artists are feeling compelled to execute.

I totally agree. Thank you so much Saj.