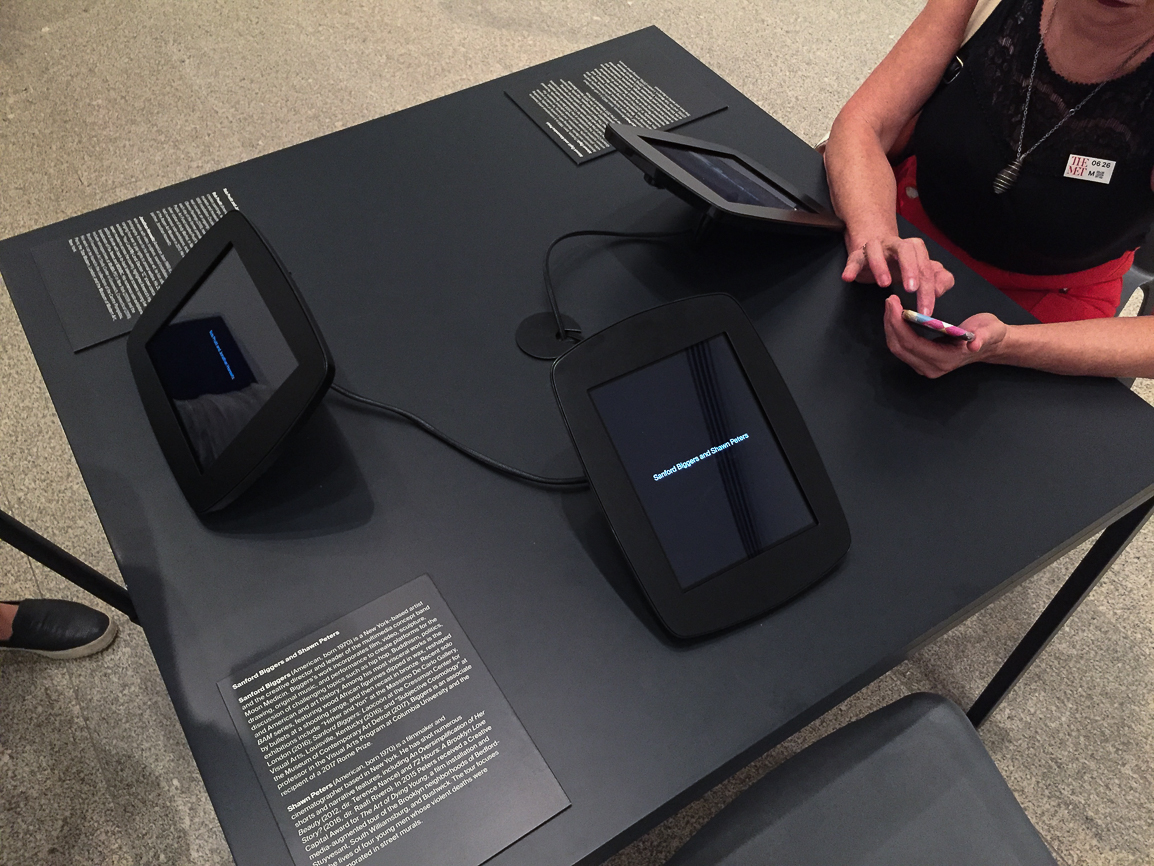

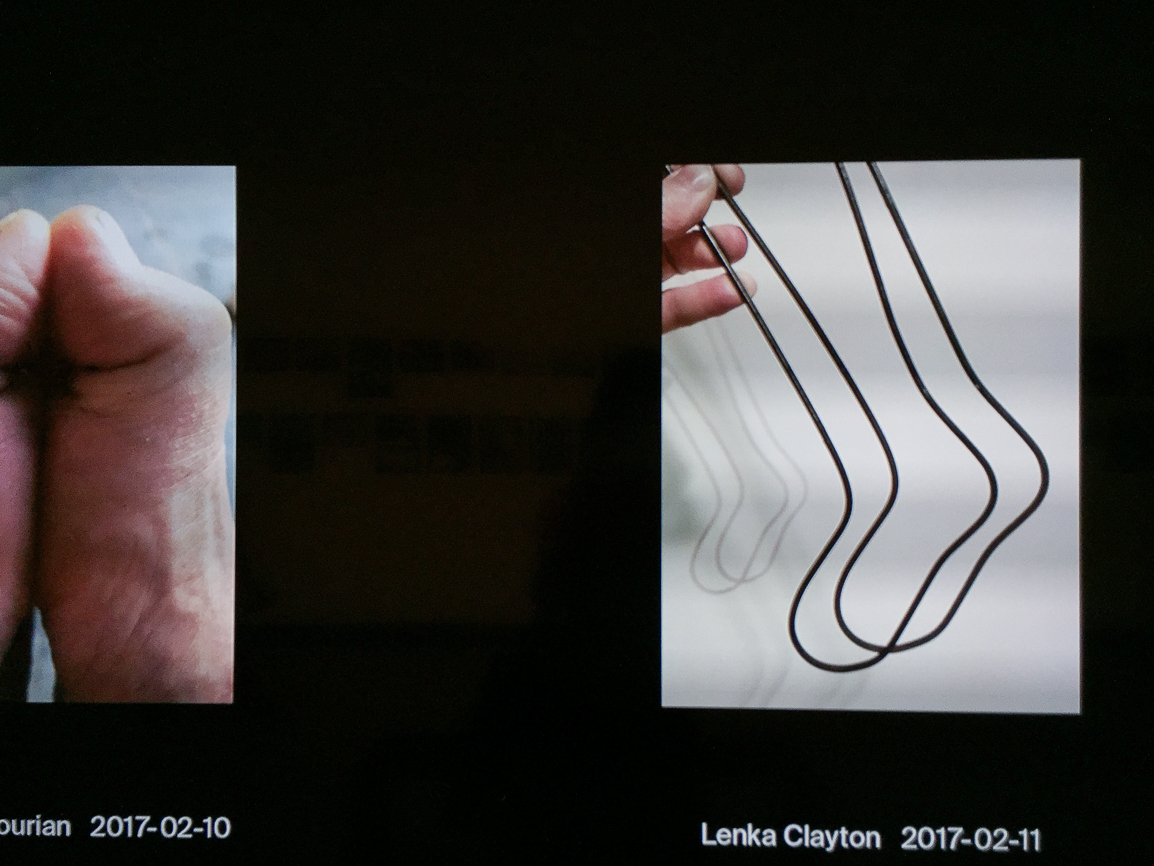

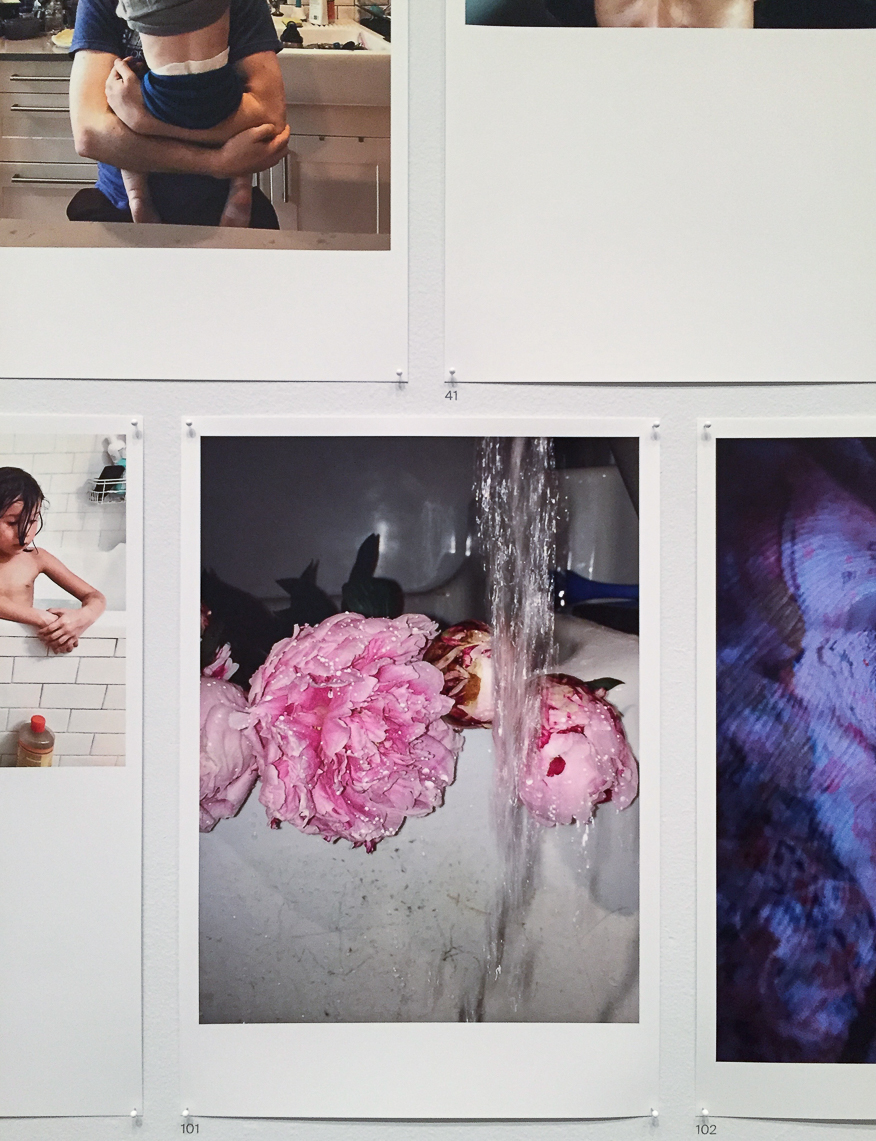

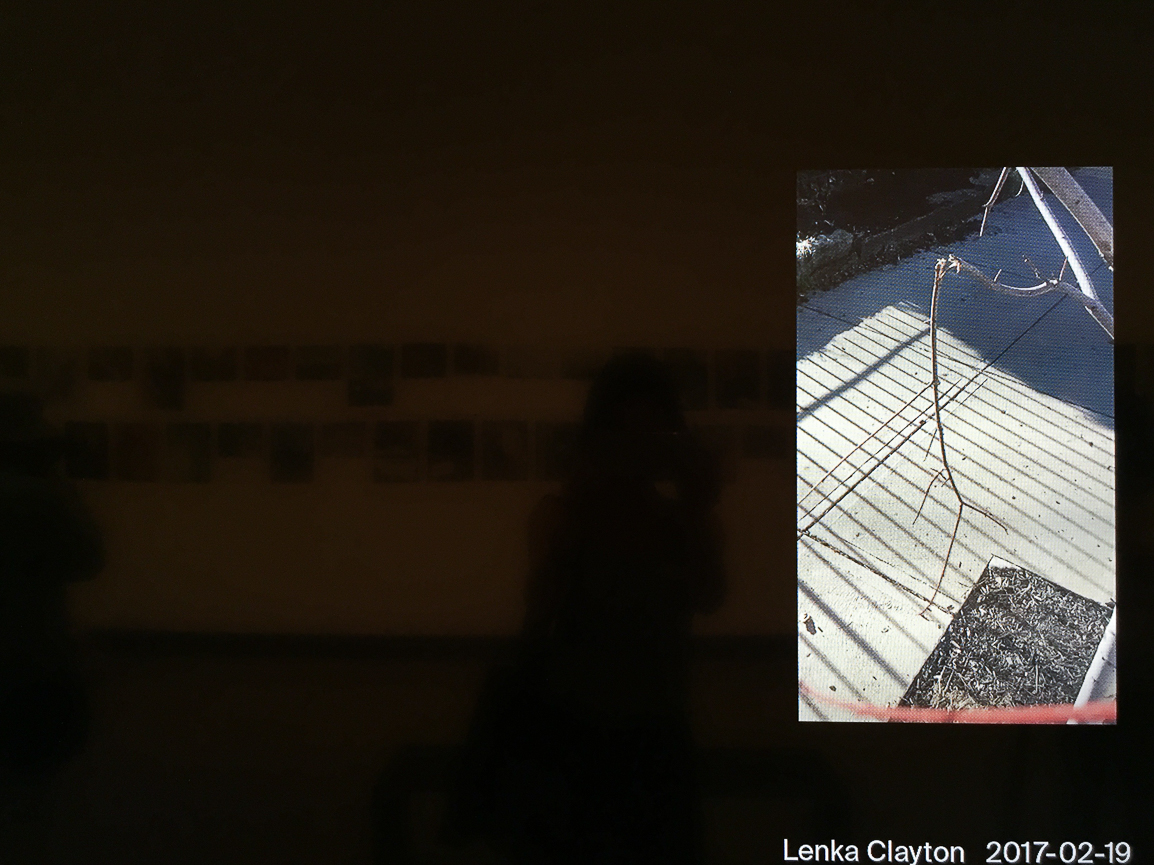

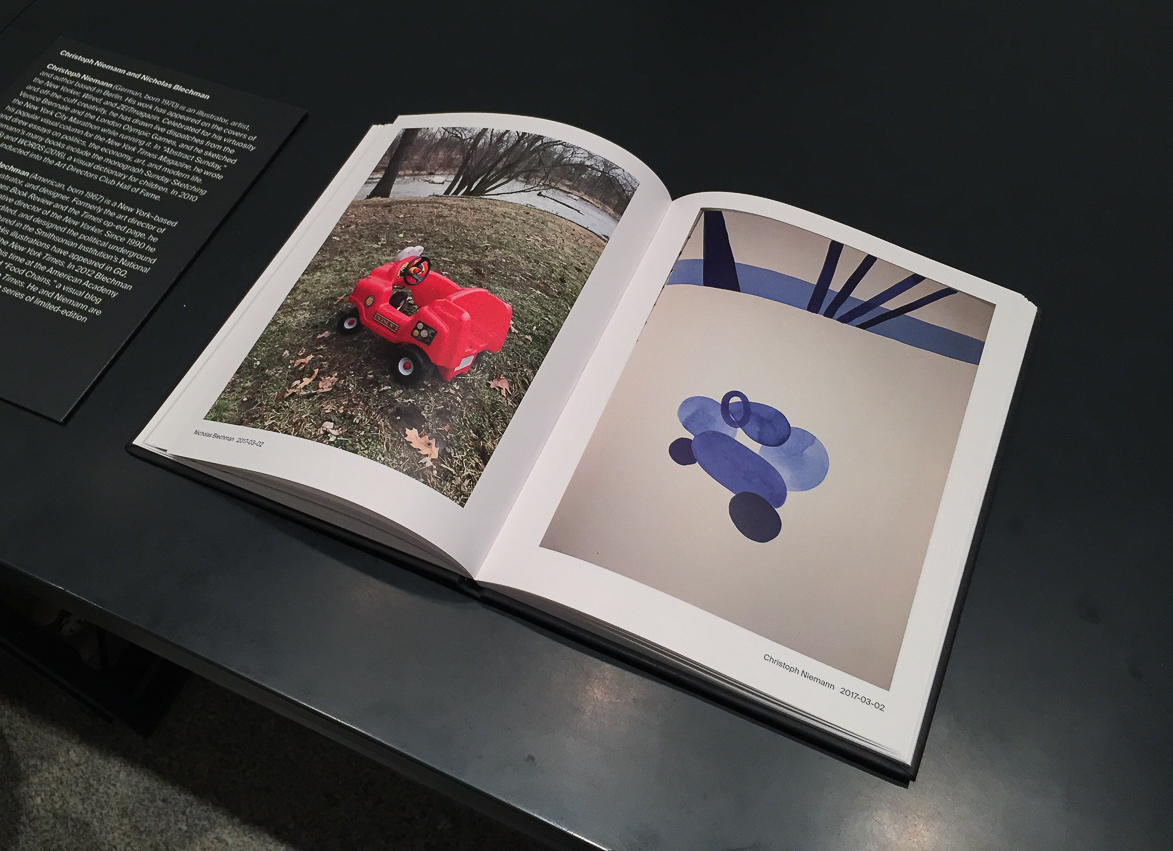

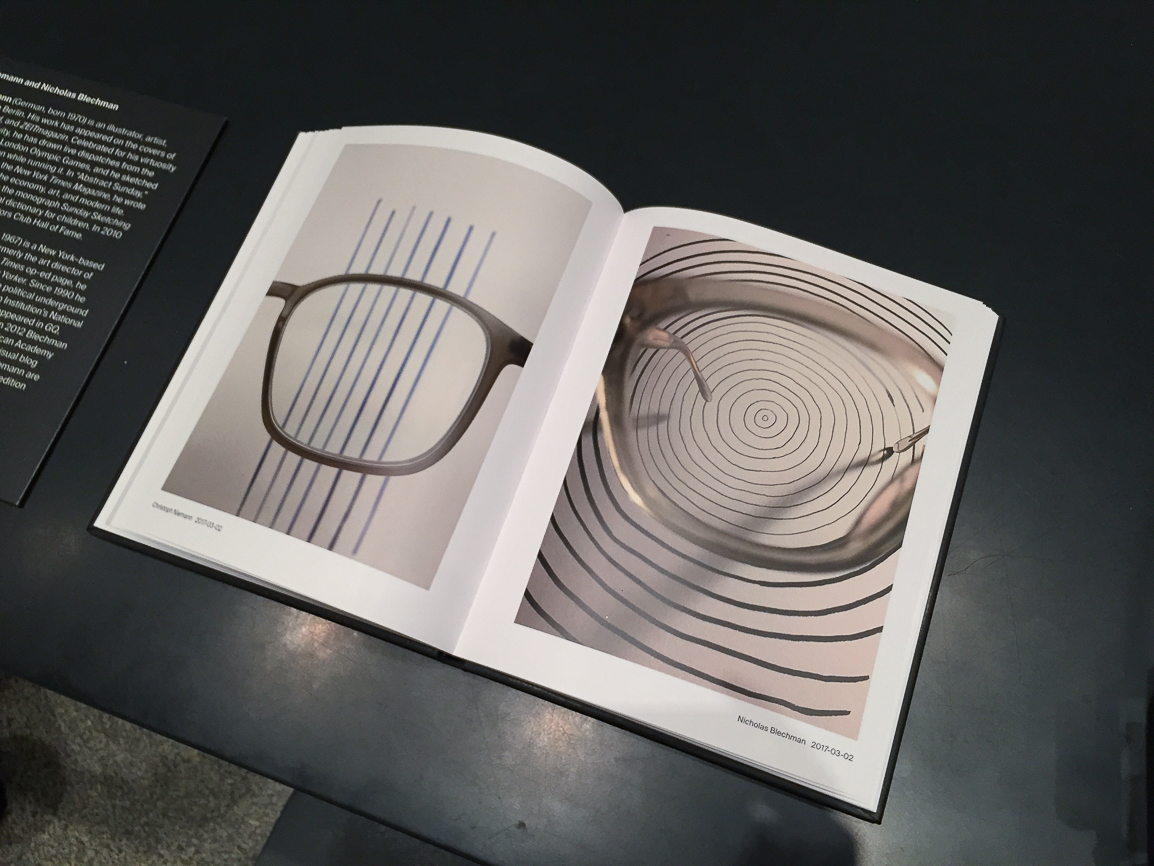

Fine Art Through the iPhone

'Talking Pictures: Camera-Phone Conversations Between Artists' will be open through December 17th, 2017.

Stay informed on our latest news!

'Talking Pictures: Camera-Phone Conversations Between Artists' will be open through December 17th, 2017.

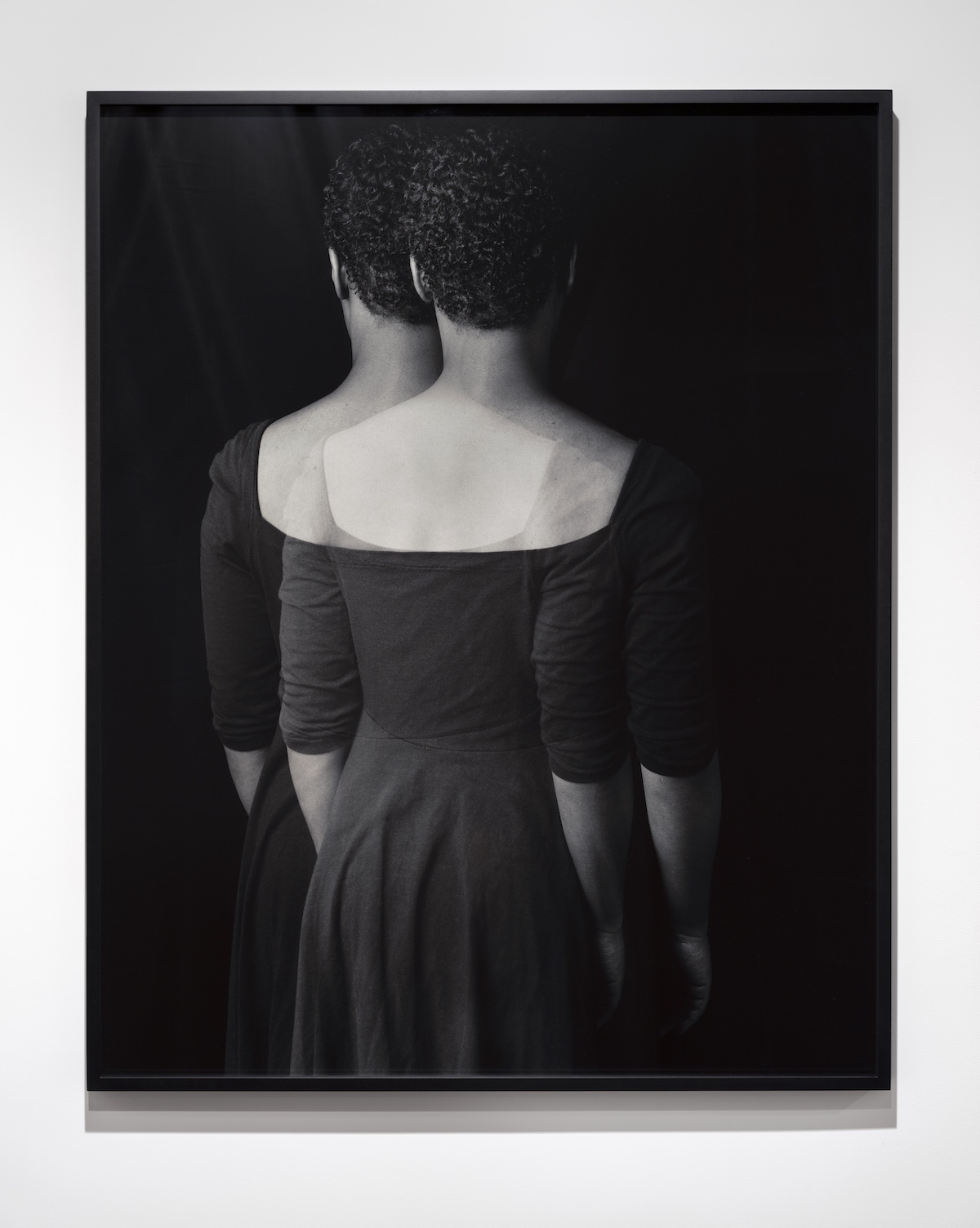

A long lineage of Black artists that have engaged the “edge of visibility” make up the ideological ancestry of Going Dark. “The traditional esthetic of black art, often considered pragmatic, uncluttered and direct, really hinges on secrecy and disguise,” Guyanese-American painter Frank Bowling wrote in his 1971 essay “It’s Not Enough to Say ‘Black is Beautiful.’” “The understanding is there, but the overwhelming drive is to make it complicated, hidden, acute.” In the following decade, artist Lorna Simpson would turn on Bowling’s secretive hinges – a 180 degree turn, to be precise — utilizing the compositional device of the Rückenfigur to deny the viewer’s gaze by turning her subjects away from the camera. “I am invisible,” says the unnamed narrator in Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man, “simply because you refuse to see me.” For Simpson, however, the power of her images lay in reclaiming the power of that refusal for the subject. The elusive eponymous figures of Faith Ringgold’s paintings Black Light Series #3: Invisible Man #1 (1968) and Black Light Series #3: Invisible Woman #1 (1968) also derive their (in)visibility from a refusal to be fully seen, as do the figures in Kerry James Marshall’s paintings Invisible Man (1986) and Two Invisible Men (1985). In her Invisible Man Series (1988-1991), which documents the residents of a Harlem neighborhood, Ming Smith withholds the identities of her subjects by intentionally producing blurred and low-light images — refusing to deprive them of their anonymity.

For some of the younger artists in the show, going dark is a strategy to evade the pernicious shadow of surveillance and overexposure in the digital age. Some artists in the exhibition go dark by literally darkening their images and paintings, using pigmentation, monochrome, opacity, or lighting techniques; others modulate their (in)visibility through material selections and print methods; still others go dark by way of technological interventions like chroma-key greenscreen/bluescreen and Photoshop.

Since James began her tenure at the Guggenheim in 2019, the (art) world has seen a drastic upheaval in how it navigates issues around race, reaching a fever pitch in 2020 after the killing of George Floyd. That turbulent “reckoning,” as many have called it, has seen an equally inelegant decrescendo in the years since. It is difficult to engage with the questions posed by Going Dark without calling to mind the art world’s habit of tokenizing Black curators; when David Zwirner hired curator Ebony L. Haynes to head a new gallery at 52 Walker in 2020, the opening line from the New York Times announcement of her position referred to her merely as “a gallerist who is Black”; the Times article announcing Dr. James’ own appointment in 2019 opened with, “At a time when museums all over the country are trying to increase the number of people of color on its staff, boards and walls, the Guggenheim Museum has hired its first full-time black curator: Ashley James.” Going Dark’s engagement with the precarity of representation feels especially timely, arriving at a moment when the diluted mainstream agenda of identity politics seems to be collapsing in on its shallow foundations.

But that timeliness wasn’t on James’s mind as she assembled the exhibition. “I never like to think about my exhibitions as responding to the cultural moment,” says James, who earned her PhD from Yale in African American Studies and English Literature. “Black studies has always had a really skeptical and complicated relationship to representation — the question of representation is endemic to my field.” As for her own place in that relationship: “I wouldn’t say it was an autobiographical working-out of a question, but in the same way that I say that representation is just a critical discourse of the 21st century, it's not a surprise that I would then be implicated in that too,” James says, sounding somewhat surprised that I made the connection. “I'm certainly aware of what my position vis-a-vis the museum is in terms of my blackness,” she concedes. “And that I'm the one going dark, or forcing the museum to go dark, and ushering the Black people into this white space.”

While Going Dark marks James’ second exhibition at the Guggenheim, it’s her first in the rotunda. She worked on the exhibition and catalogue for about a year and a half after settling on its concept. Between spring of 2022 and the opening of the exhibit in October 2023, James spent a lot of time with replica models of the familiar white spiraling ramps and clandestine bays of the rotunda. Filling a space of that scale presents a unique challenge for a curator, but such a distinctive venue can also engender new ideas. It was in a meeting over one of those replica models that American Artist and Dr. James came to a realization that birthed the former’s site-specific installation Surveillance Theater (2023): the Guggenheim resembles philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s late-eighteenth-century concept of the panopticon. “As a correlation, I think it's a little on the nose, but at the same time a lot of people don't necessarily think about that,” says American Artist. “The only thing that's missing is this central tower.” In place of that tower, they created a conspicuous globe that hangs from the oculus above the rotunda, recording visitors through 360-degree CCTV cameras. From the camera’s view, everyone in the rotunda is visible — for better or worse.

“Knowing the scale and significance of this institution, I wanted to do something that I felt would play with the uniqueness of what that opportunity allowed,” American Artist explains. “I was thinking of people visiting as a component in the work — the average Guggenheim Museum-goer, what are they expecting? What if I show the way that this museum and all museums are implicated in this relationship with the courthouse, the university, the jail, the factory, the airport — all of these things have similarities, especially bureaucratically and economically — the way that even beyond my piece, you have to go through security to get in the building. I wanted to do something that feels like it's everywhere, and I think the surveillance aspect played into that.” Behind a curtain in one of the rotunda’s bays are several 4K monitors that display a live feed from the camera, equipped with an AI software that matter-of-factly and somewhat touchingly identifies each moving visitor with the onscreen label of “human.” But in order to enter and view the live feed, visitors must first relinquish their phones and place them in small locked pouches provided by an attendant. To have the pouches unlocked, they must return to the ground floor of the museum. According to American Artist, the idea of temporarily dispossessing visitors of their phones preceded the rest of Security Theater.

“I think of it as a sort of trade-off for this abundance of visuality,” they describe. “That room as an offering was an attempt to seduce people into being willing to give over their phone, and then partake in that experience of not having their phone. Most people think it's the other way around, but the room is actually there to get you to give your phone away.” Those who continue after Security Theater, instead of immediately descending to unlock the phone pouch as I saw several visitors do, experience the remainder of the exhibit disconnected to the digital realm. In my own visit to Going Dark, I was immediately struck by how naked I felt without access to my notes app or my camera — and powerless to access my own tool of surveillance and documentation.

Tiona Nekkia McClodden’s series of paintings Very, Very Slightly (2023) also seduce the viewer into participating in the work, in this instance with prayer benches placed in front of the paintings atop a plush red carpet. The paintings depict advertisements for Black femme mistresses pulled from 1960s and 70s BDSM magazines and are printed on leather, a material that appears often in McClodden’s work. The figures of these women are rendered in black, blue, and red dyes and the diamond dust that gives the paintings their name: a type of diamond known as “very very slightly” or VVS for its subtle flaws that create a distinctive sparkle. The women in the paintings are elusive to the eye and — as I learned when I submitted to the prayer benches — most visible when one kneels before them.

“Especially with the red carpet, I'm definitely thinking about churches, specifically Catholic churches, and spaces of piety and prayer. But there's this other aspect of trying to figure out how to tease at people's desire,” McClodden says. “The best view is on your knees, and that's just it. I had to get on my knees repeatedly to make this work, so I'm transferring something that I enacted for myself.” Very, very slightly diamonds or VVSs are popular references in music, particularly in hip hop — I personally think of the VVS cufflinks promised by Beyoncé to her lover in the “Upgrade U” outro. “I am a child of hip hop, and I was born and raised in the south. I heard it but I had no idea what VVS meant. I was too poor to. And then I got to a certain age and I found out. The idea that the diamond that Black people like the most is beloved because of its sparkle and its imperfection and its shine: I was like, oh God, how beautiful and poetic,” McClodden explains. “And then thinking about leather and the idea of employing it… leather is fine over time, but it still has to shine. “Very, very slightly” is literally how I have to deal with the leather. I can't be abusive to it, otherwise it rejects the work that I'm trying to give it. I thought that it would be something very beautiful to bring my cultural relationship to the diamond and blackness, and think about these Black women as these kinds of diamonds, and figure them as such.”

Very, Very Slightly addresses the connection between the erotic and the unseen more directly than any other work in Going Dark. As both a member of the BDSM community and a contemporary artist with aversions to hypervisibility, McClodden has spent a lot of time thinking about the kinds of pleasures that can only be sustained away from view. “I like to play in the areas of distance,” she says. “I'm not exactly interested in going there all the way — I like not consuming something because it makes me still have a desire for it. In this time where I think there is a desire for the audience to consume everything, to consume ideas, to consume the Black figure in a certain way, I have to have some obscurity to also allow distance and sustain my own desire for my own work.” Her unwillingness to offer herself up to that kind of consumption in tandem with her work is part of why McClodden chooses to live in Philadelphia, where she feels she can maintain a greater anonymity. “Visibility as someone who often tries to hide is really something I'm always dealing with trying to negotiate. Currently I’m at this point in my career where I'm reclaiming a particular space and visibility of how I want to be seen, how I want my work to be seen.”

American Artist echoes a similar apprehension of the visibility that accompanies their practice and career. “The further I get into my work, I want you to just spend more time with the thing I'm trying to say, and I feel like it's going to happen less and less.” When I ask what makes them feel the most exposed, their reply surprises me. “This show. I think the visibility of this show in our professional sense is really next level,” says American Artist. “The idea that anyone could come up and see this thing that is very close to me and has been close to me for a long time does feel sort of exposing.”

To close our conversation in the Guggenheim’s reading room, I ask the two artists which would frighten them more: to be seen always and completely, or never at all?

“To be seen always and completely,” McClodden answers. “I've spent the majority of my life being overlooked, even in the more intimate spaces of family and everything. I was such a quiet kid. I distinctly remember thinking I could be invisible or something. And as much as that could be a painful thing, it actually is immense relief right now, which is what I like. As soon as I get back into Philly, I'm invisible.”

“To be seen never at all is more frightening to me,” American Artist says swiftly and decisively.

As I thank the two artists for our conversation and gather my belongings, I think of the words of Fred Moten: “I believe in the world and want to be in it. I want to be in it all the way to the end of it because I believe in another world and I want to be in that.” As I emerge from the museum, I mentally prepare myself to be in the world again — to believe in it, to relent to its gaze. I prepare to be seen.

"Going Dark: The Contemporary Figure at the Edge of Visibility" is on view at the Guggenheim from October 20, 2023 until April 7, 2024.

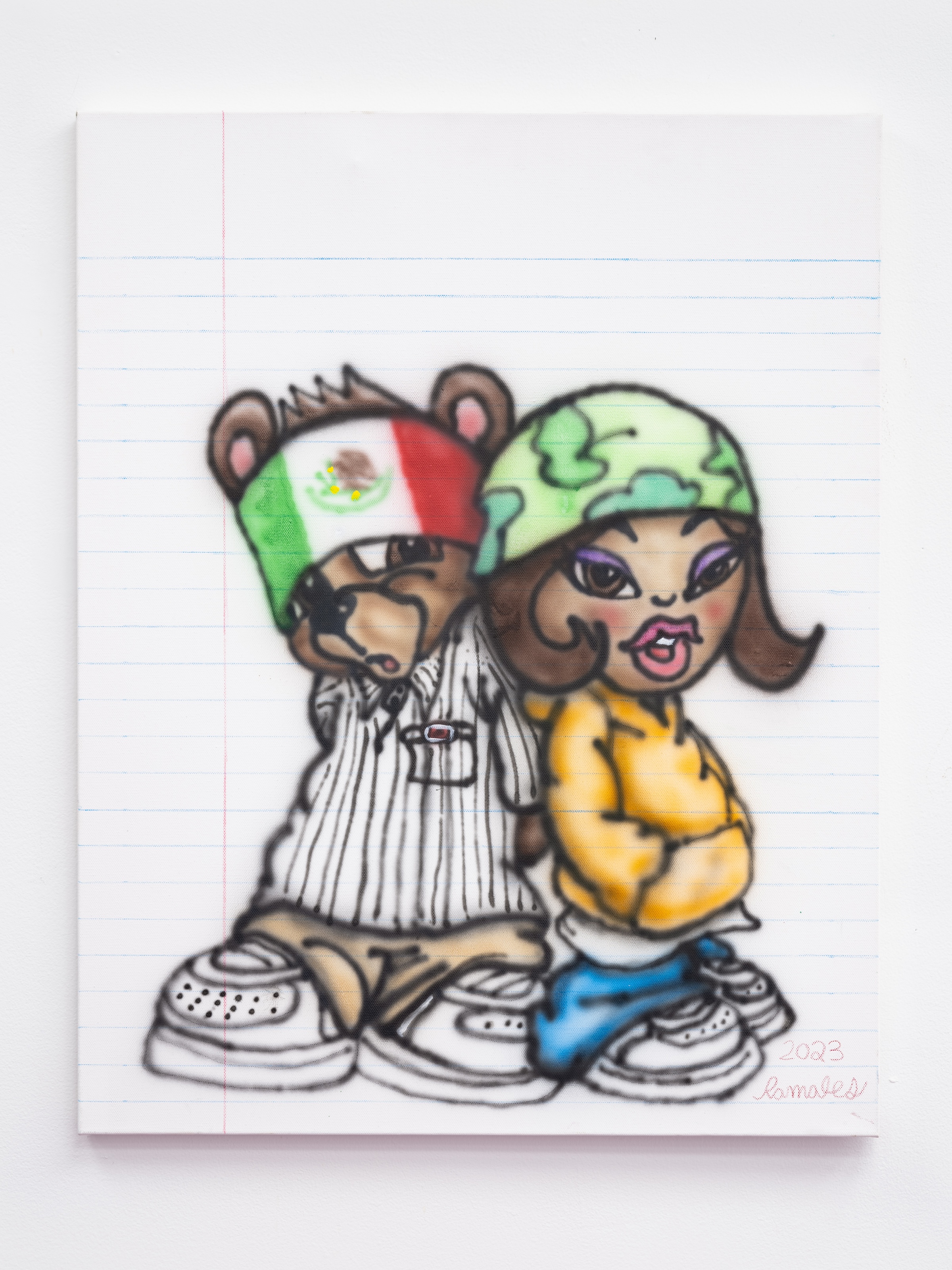

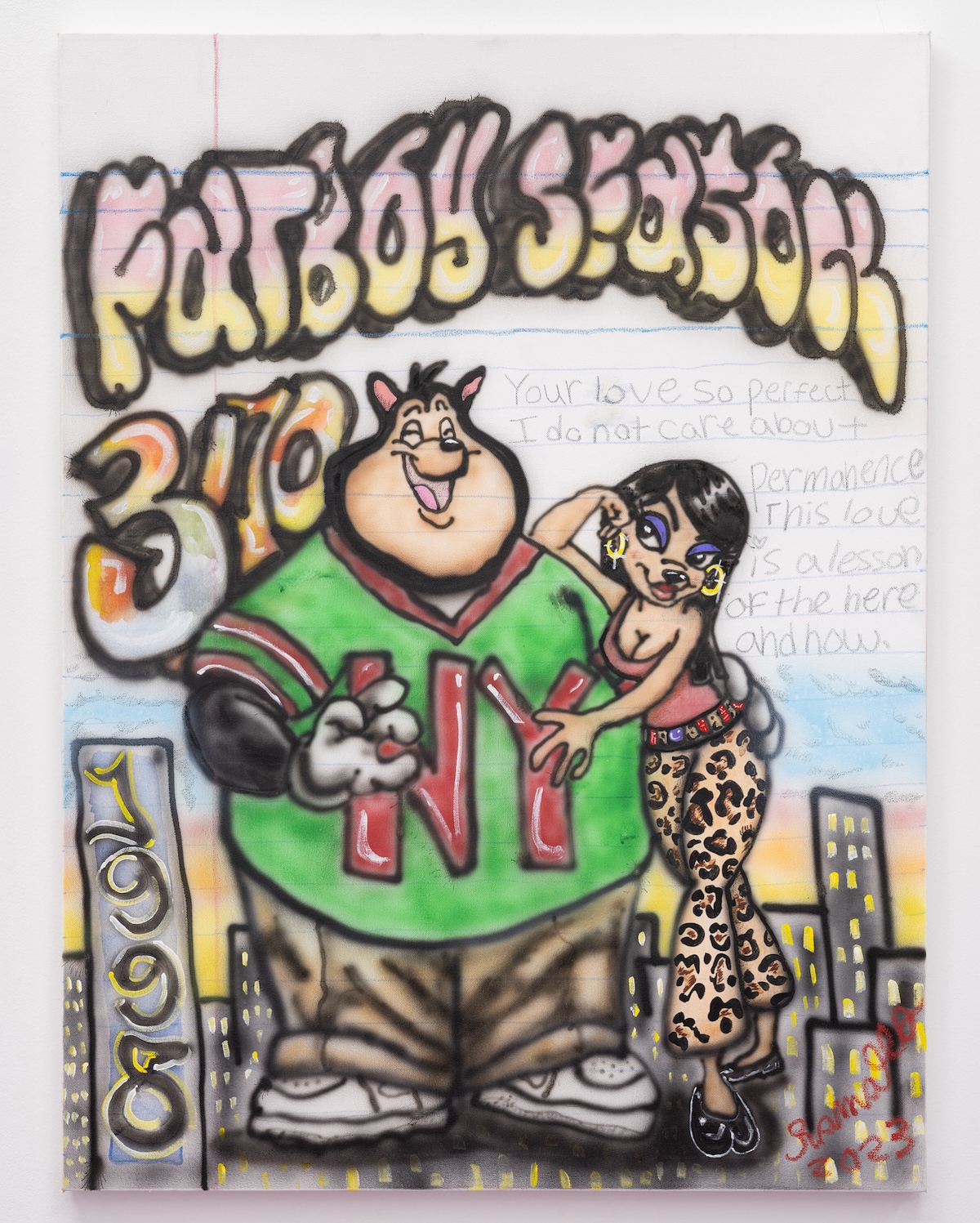

Using colors that are simultaneously “too dark and too bright,” Dorrey unveils a “fragile utopia amidst digital chaos” where “Black joy emerges even within the bounds of a grotesque haze.” On the other hand, Ramales’ playful assemblages combine "emblems of faith, cartoons, and imagery from the artist’s everyday life" to tell stories that straddle the balance between fantasy and reality.

Made on his phone, Dorrey’s exaggerated photo manipulations and distorted characters evoke the familiar haze of memories squeezed into the fanciful confines of a dream, while Ramales’ cartoonish depictions take on an unexpected realism. Ramales often combines painting with found objects. His love letters on old composition notebook paper and figurative depictions place an emphasis on “Mexican and American working-class iconography and totems of Roman Catholicism”, while drawing from accessible cultural references. Alongside one another, Dorrey and Ramales' bodies of work, while different in style and reference, seem to tell separate parts of the same story.

See for yourself at 15 Elizabeth St #113, New York, NY 10013.

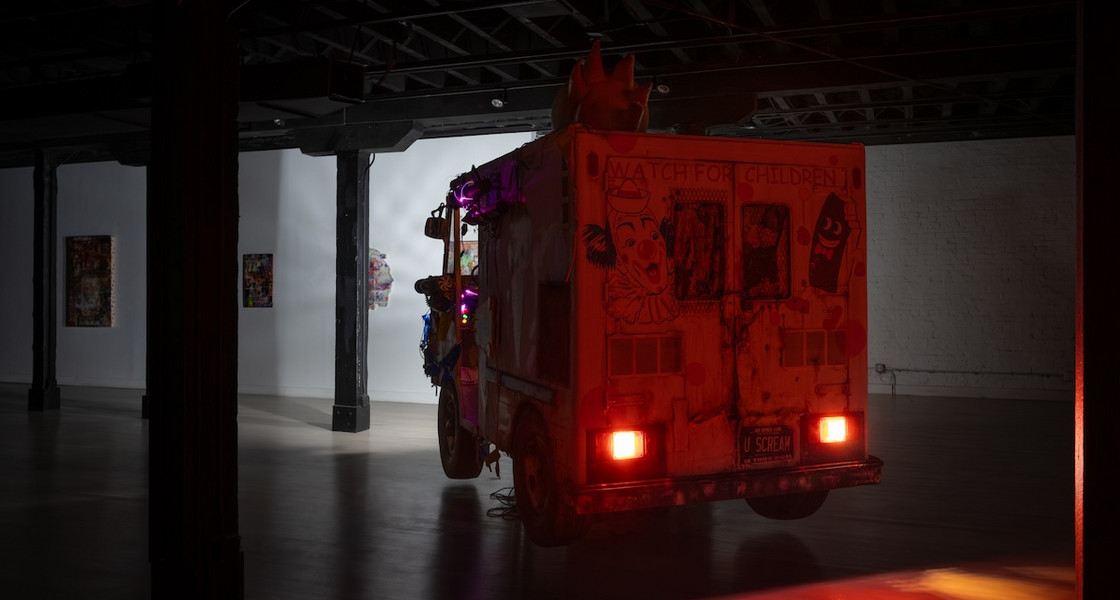

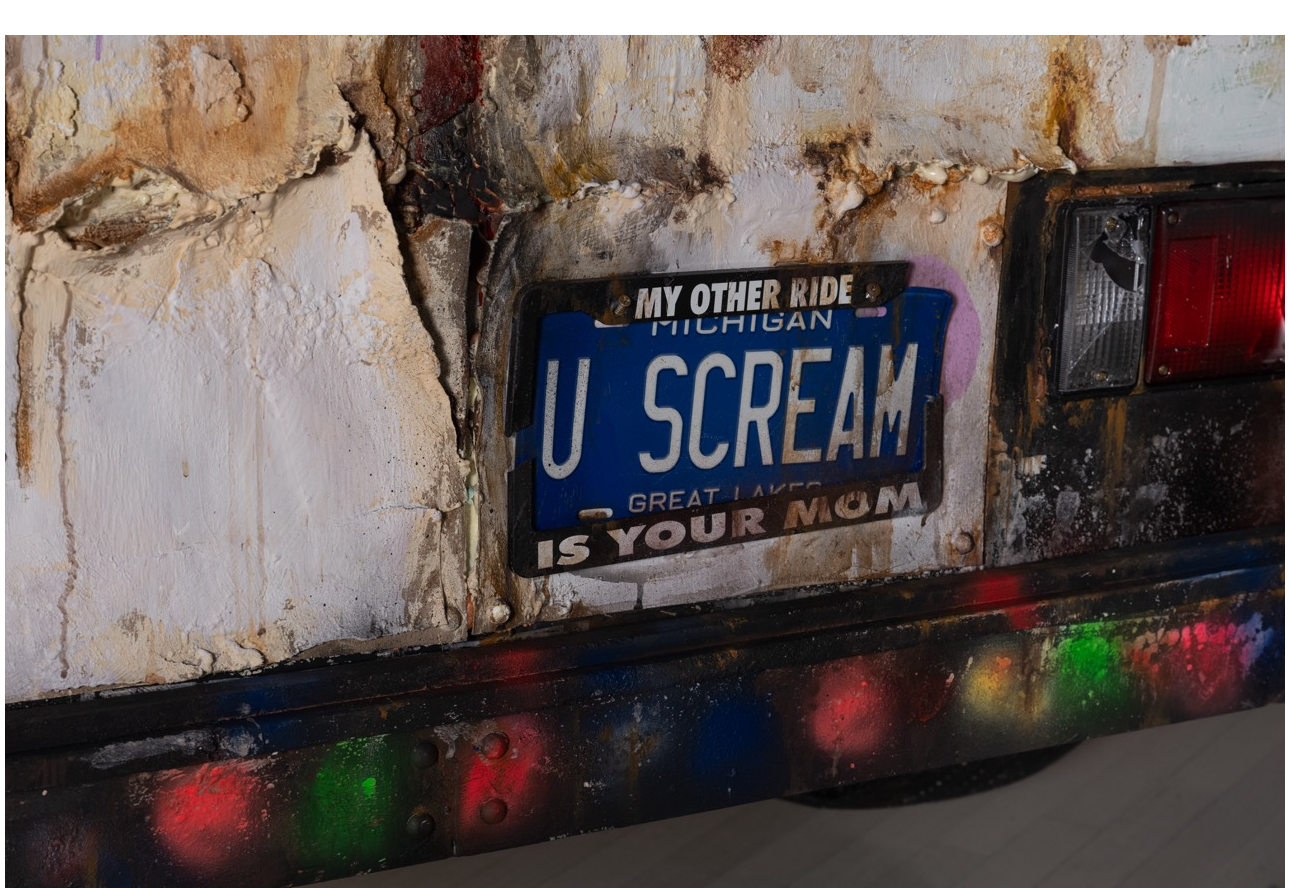

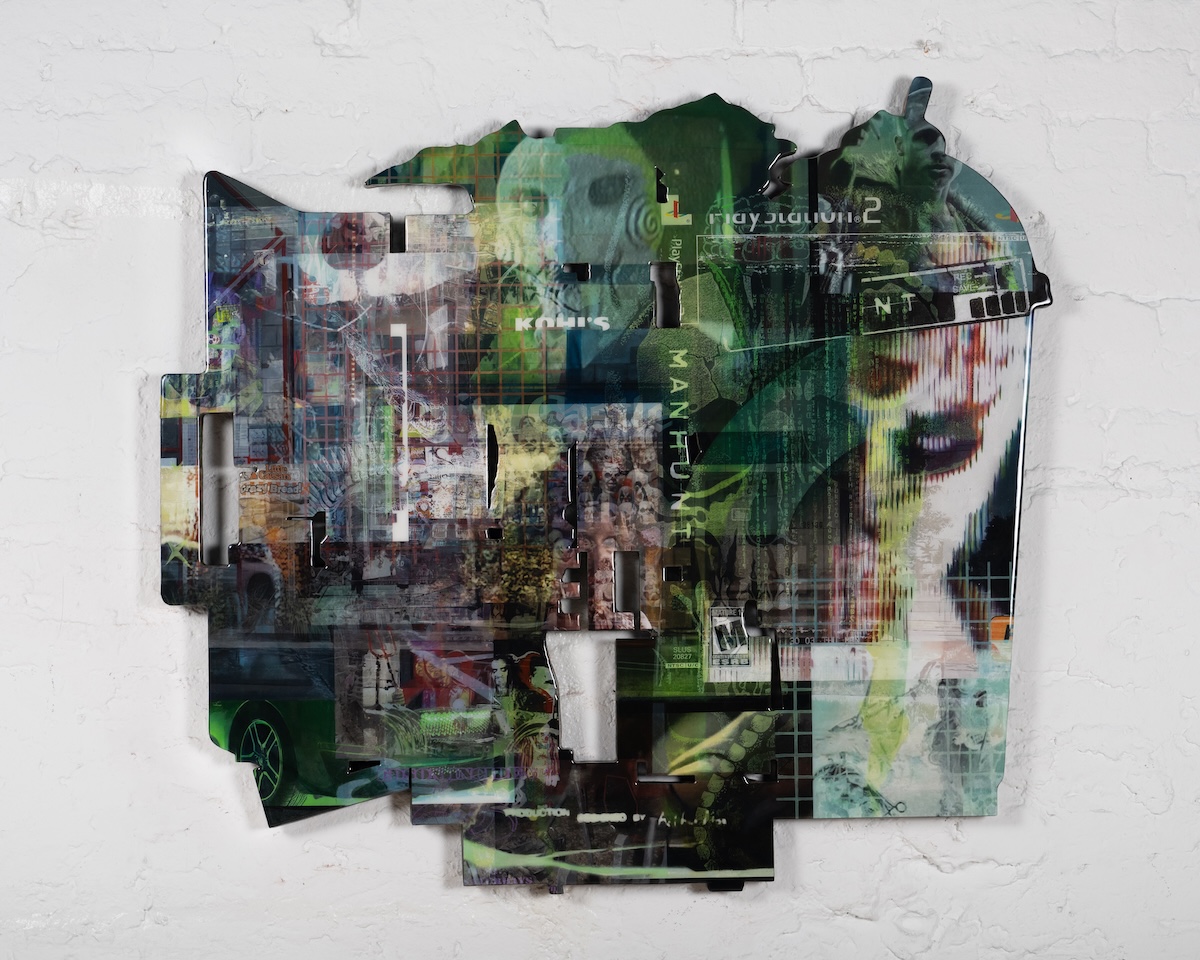

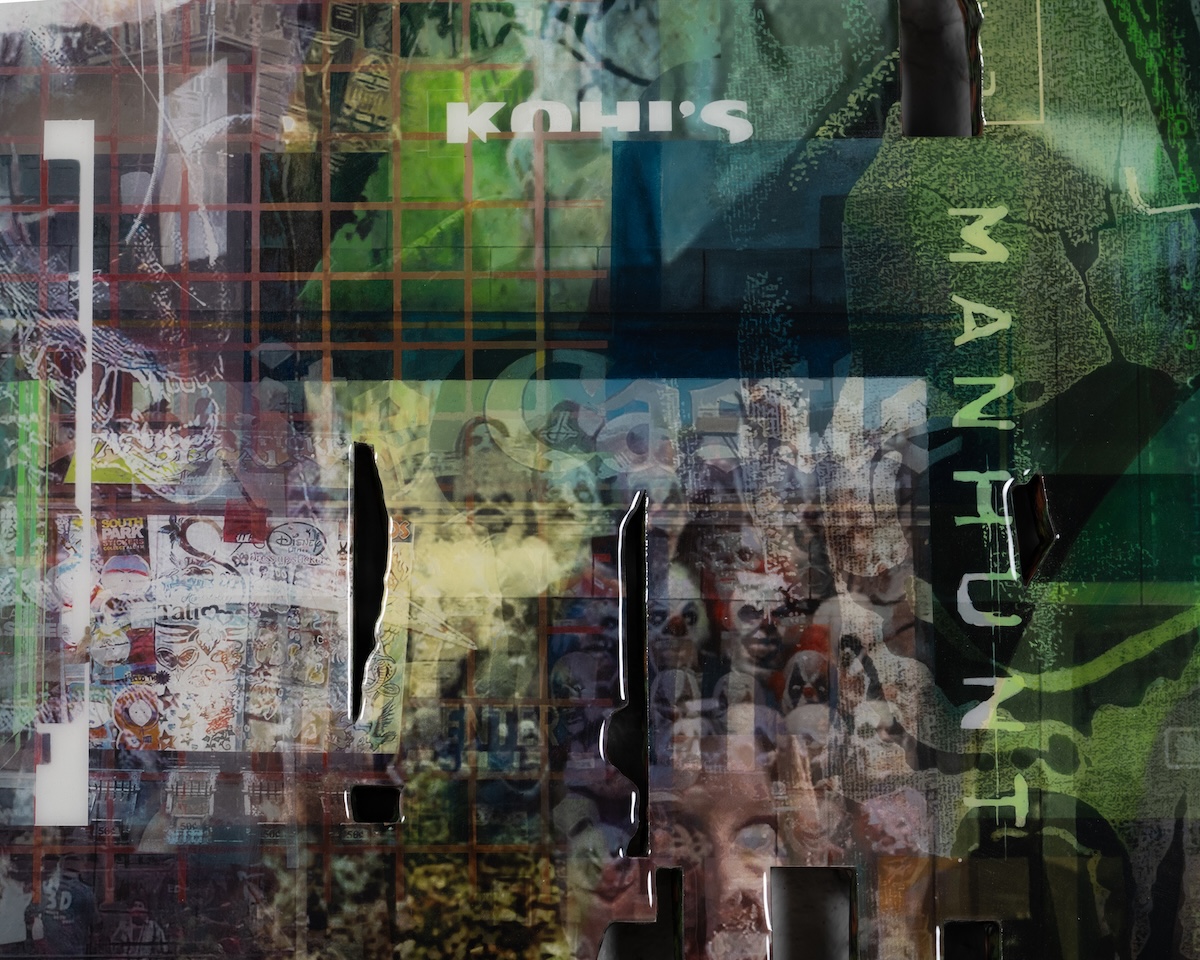

His series of acrylic collage paintings cleverly blend Christmas imagery with classic cereal logos, video games references, and archival stills from holiday commercials and ads. A life-sized ice cream truck embellished with a giant clown head serves as the exhibition’s centerpiece, acting as a source of light that illuminates the entirety of the exhibition as it moves around the space.

Hope draws perpetual inspiration from Detroit, finding beauty in the remnants of deteriorated architecture and the individuals navigating the outskirts of society. His ability to create entire worlds based on his surroundings, from sculptures made of bones at Yale to crafting Hell-themed sets for Insane Clown Posse, showcases his experimentation with non-traditional mediums. This exploration takes on new meaning in his exhibition, offering a nuanced interpretation of the holidays — not just the joy and cheer, but also the sorrow, anxiety, and fear that can arise during this period. office sat down with Hope to talk holiday frenzy, childhood mall runs, and American car culture hubs.

What's your relationship with Detroit like?

Everything around me is an endless source of inspiration here. It's sort of a ghost town, a wasteland of a city. I like to tell anyone who comes here about the city’s history and what had happened after the riots in the 60s. People that left created all these really perverted communities (the subs) around the city that had no real relationship with it.

Is there a time in your life that you return to for inspiration the most?

It’s probably obvious in the work but childhood and adolescence. I’m 34 and when I look back it seems like it was just yesterday that all these things were here. Now I see my nieces and nephews growing up having a stark relationship to people, surroundings, and technology. I always go back to when I didn’t have problems and the world wasn’t so complicated. It’s what fuels a lot of the work I’m doing right now.

What made you think of the ice cream truck?

It’s a specific reference to a video game in the 90’s called Twisted Metal. It’s kind of like a Mad Max future where you can be a crooked cop, a gang banger in a lowrider, or you can be a clown in an ice cream truck — you can pick up missiles and throw them at each other. As a kid in the 90’s, I remember getting that game and feeling it was a very strange free-for-all release valve from angst that kids have when we’re young. I was trying to think of something that wasn’t so corny. I wanted a serious, honest attempt to recreate something that could be blended with a painting show to be used as a lighting element, slowly panning across to reveal paintings around the space. The truck came out of those worlds colliding and scaling up something that doesn’t exist. The whole thing is made out of foam, which I had to engineer to rotate because it could only handle 140 pounds.

What was the process like?

I don’t usually plan, like I don’t have a journal filled with ideas. It usually comes from someone saying something like, We should do a solo show, then I’ll talk with the gallery and come up with ideas. I like to work with them and understand the gallery’s interests, while also testing the waters. Todd’s a pretty cool guy, so the weird far out shit that no one in the art world would understand, he’s into. That’s where I shine because I'm kind of an outsider in the art world. He’s on board with me saying, I’m just going to build a giant murder clown ice cream truck with guns everywhere. It might scare some people, but that’s what I’m excited about. 90% of the art doesn’t excite me these days.

Why Christmas for the exhibition?

I planned for the show around Christmas Time. It’s so… I don’t want to say tacky, but expected to have an art show about Christmas during the holiday season. But when you get to the show, it’s very dark, scary and kind of depressing; very overwhelming in all senses; there's different sounds and scents too.

What types of sounds and scents?

I got a bunch of wallflowers at Bath and Body works. The scents are under the Christmas tree, cinnamon sticks, and a perfect christmas. The gallery is so big you could stand in different zones and smell pine trees. Then you go into a different place and it will smell like those awful cinnamon pine cones they have at Joann Fabrics. I wanted it to be overwhelming and exhausting. That feeling when you walk into a mall and you don’t know where you’re at, as if you’re being abandoned in some kind of fun house. There is also music inside the truck that’s playing — a track with a bunch of different Christmas music, adding a bunch of reverb, so it sounds like you’re in a mall that’s really empty and the music is far away. It’s like what clout rappers and kids use to make vapor wavvy songs.

Are the pieces a vessel to critique the commodification of the holiday season?

I think that’s always there no matter what you do, especially when you're dealing with work that has commercial imagery in it. I’m reflecting and contemplating what all these symbols and images mean to us. It’s not as much critiquing it, or saying it’s a bad or good thing necessarily. I am saying these are things that are a part of our everyday life. There’s no hidden agenda to the work themselves. It wasn’t meant to be like a theoretical analysis of consumer culture, consumer waste, or what the companies are doing. It was more so these are everyday things that we need to survive and entertain. The critique lies in our relationship to those things and what it makes us criticize about ourselves. We’re suffering out here and unstable as a whole.

How do you hope to portray where you're from to someone who has never been there during the holidays?

I’m fascinated by these things that come around every year. We have these habits, like getting a Christmas tree and decorating it. A lot of what is in the collages are familiar images that are warm and fuzzy yet deeply sad. Holidays always bring up this remembrance of people or places we don’t have with us anymore. I always think about going to the mall with my family as a kid. My grandma and my aunt worked at a nail place in the mall so we’d get dropped off with them. We didn’t have any money to buy anything, but we would be out there because that was the social scene of the 90’s.

Growing up in Detroit, we never went downtown for anything. To see that all those places are gone now, all we have are our memories. I’m always dealing with ghosts or zombies in a sense of these being dead elements that I try to return to and breathe life into. It’s like manifesting this mental slice of your brain at some place in some way.

Do you have a favorite piece in the exhibition?

There’s a really big collage one, a Christmas-themed one. It has Freddy Kruger on it and there’s a target sign. It’s a really compressed black hole or like a neutron star of Christmas. I wanted to convey that anxiousness of early and mid-December, where you go to work, stop here, stop there, grab dinner ingredients, it’s snowing out and you’re feeling tense. Thinking about all these gatherings to organize, dates to keep track of, presents, kids, dealing with in-laws. This one I feel most captured the static frenzy of the season.

Is your intention with your work to reframe people’s misconceptions of the rust belt, like a new poetics?

[Laughs] Kind of. When I think of poetics, I think of romanticism and going to live in the wilderness, letting the sublime of nature take you over. That’s kind of what it is in the work, being thrown into a circus of different lower middle class car culture people. I’ve tried to communicate their existence through a lot of my work. Juggalo culture is an obvious one, but there are so many niche things — like people who own reptile stores or who collect reptiles or Betty Boop moms who love I Love Lucy.

I get it. It’s refreshing to see that portrayed through your pieces. A lot of artwork is centered around New York and LA, but there’s so much more than these two places, along with many more interesting topics to draw upon than repeating the same dialogue.

Yeah and I think that is why I try to stay out of the art world as much as I can. There’s so many voices there already who don’t have the capacity or the sensitivities to their identity to be comfortable talking about their true interests and making work out of it. So many people just move to New York and fit into the six different categories of artists in NYC. I’m not seeing anyone embracing any other line of thought.

Once a month, I’ll scroll through NADA’s fair and I get excited because I feel like I’m doing something not there. Ok, either no one likes it or isn’t paying attention to be like, Hey we need to start doing something weird because we’re all making the same thing. Artists in general, what we have to represent and get out there is our community, our voice, our own independence, and our tribes.