Fragmented: Yeni Mao

Born in Canada in 1971 to Chinese immigrants, Mao was brought to Michigan as a baby, where he would live until his departure to New York in the 90s. Art has always been a fixture in Mao's life, motivating his decision to study and earn his BFA at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The 90s art world was very different than today's, where diasporic voices and artists of color were discounted, either ignored or misunderstood. This culture of exclusivity prompted the then-New York-based artist to acquire skills in foundry work in San Francisco before returning to New York and beginning work at a design-build architecture firm. While simultaneously making art and begging more and more questions, Mao found himself in Mexico City for a residency in 2014 — a city that he now calls home. Mao's life journey has forced him to consider himself in this transnational context, informing much of his work today.

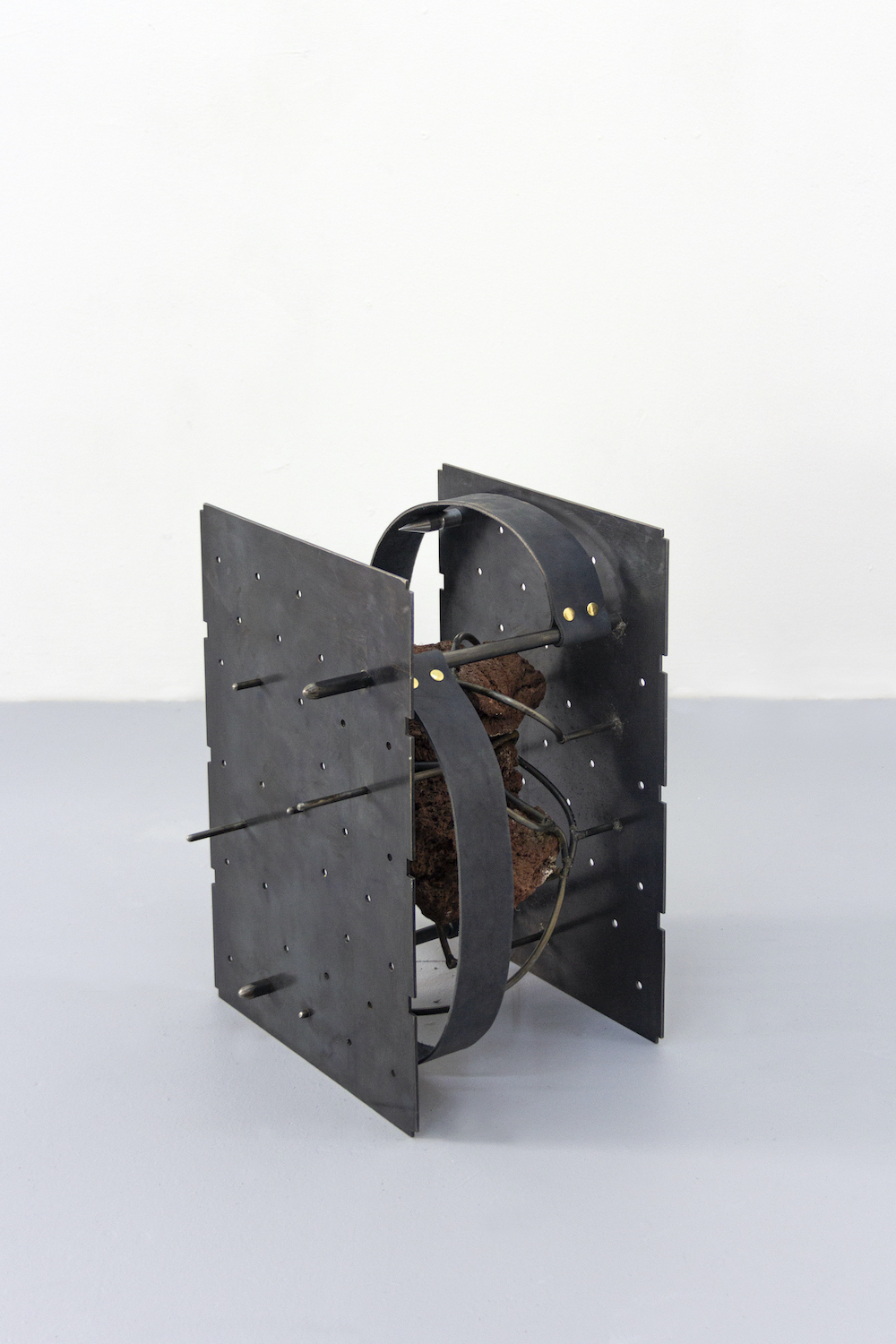

At the beginning of our video chat, Mao mentions how his forthcoming offering at Freize is years in the making. "For the Frieze presentation, I'm basing it on this research that I've been doing for some years now," the contemporary artist explains. "Freemartins" came to be through investigations into Mexicali and its "impenetrable history," a Mexican border town housing the largest Chinese population in the country. In the early twentieth century, coinciding with the Mexican Revolution and exclusionary laws implemented by the United States, the Colorado River Company exploited many Chinese immigrants through work in agriculture and irrigation. The unfamiliar climate and hot summers prompted Chinese workers to build out their basements into a tunnel system, an underground city called "La Chinesca." As the years passed and anti-immigrant sentiment began to spread in Mexico, La Chinesca became a refuge for the city's Chinese population. "Now the tunnel system is only reduced to just these few basements," Mao explains. "I have measurements of these basements. So I use the floor plans of them, and they're cut out of steel plate, and then using that as a basis of the sculptures."

Establishing an underlying — usually nonlinear — narrative is a common thread throughout Mao's practice. After pulling directly from these artifactual spaces, illuminating ideas of liminality, and addressing opaque histories and experiences of diasporic identities, the Mexico City-based artist's approach to this project has provided a basis for much larger ideas. "These floor plans are sort of loosely assembled, so they look like they are coming apart and coming together at the same time. I can use that as the basis for other things, in my practice," Mao states. "Thinking about this orality and the body and architectural space, the dissolution of bodies, and our relationship to myth. This idea that I've been playing with a lot lately of us being related to mythical creatures and sort of relating that to this idea of animism. These animals urge an intelligence of the body — beyond the spiritual mind. All that is sort of inside of these sculptures."

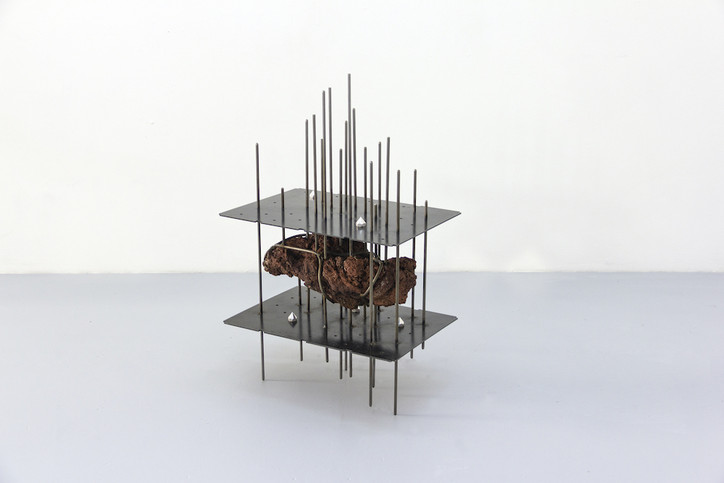

This richness of depth and embedded intentions is apparent not only in the work as a whole, but also in the details and the materials themselves. "[The material] is about this threshold or boundary, decomposition, and composition. I'm thinking about them as material that is moving through time in some way that is breaking apart," the acute artist mentions. "Steel is one of my main materials. Steel is made out of a few elements that have been industrialized into a thing, and then, it's possible that it can rust and disintegrate and go back to the earth." This notion of transience remains a pillar in Mao's practice and an essential facet of "Freemartins," engaging in ideas of fragmented histories, considerations of one's position in nature and the industrial complex, and relationship with time. Fig 39.7 Bardo, the steel armature confines the lava rock, pierces steel bars through the natural material, where a silent dialogue of ephemerality is being had.

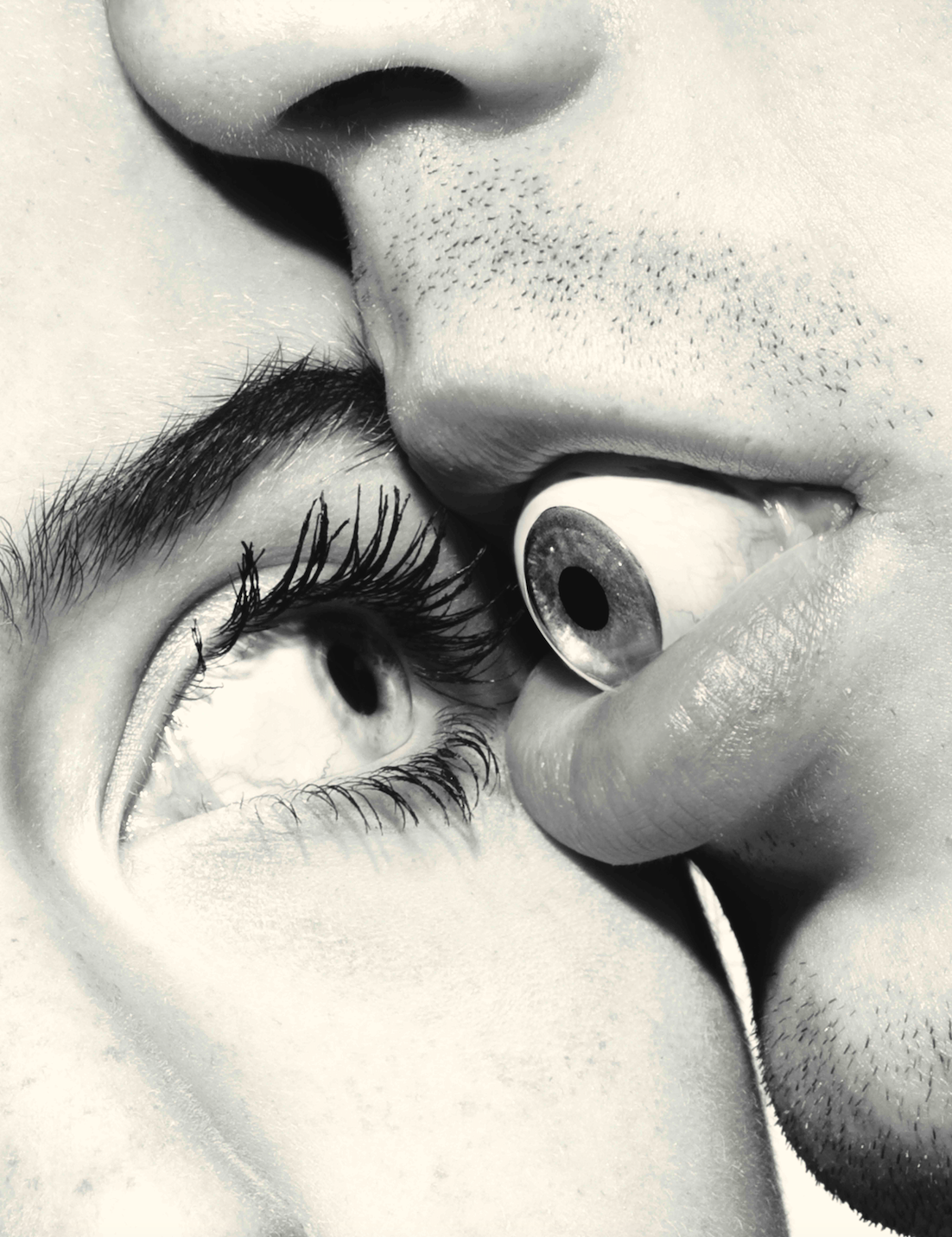

fig 39.1 freemartin, 2024

fig 39.7 bardo, 2024

Although Mao's work is laced with conceivable qualities of anthropomorphism and narrative, the work traverses realms of abstraction where discoveries offer more questions than answers. "I really believe in abstraction. And I think that abstraction is hard to talk about. It's hard to write about, but there is this sort of liberation that's happening with abstraction where I can make a figurative sculpture that's not a figure. And it can, therefore, be open enough to talk about all these other things that are happening in the world that may not be as easy to define," Mao states after taking a drag from his cigarette.

Mao's departure in 2015 from the U.S. has allowed for uninhibited artistic freedom — igniting an inner part of himself. "I'm trying to embrace this structure of poetry and this sort of weirdness and abstractness," the esoteric artist states. Since calling CDMX home, Mao has produced incredible work featured in "An array of disruptions and codependencies," in London, "I Desire the strength of nine tigers" in New York, and "Yerba Mala" in Mexico City. Some of his recent work has delved into personal history and ancestral knowledge — a new exploration for the artist. These projects centered on "My mom, dad, and my grandfather, and all this stuff that I had sort of been ignoring, or maybe felt wasn't valid or worth going into," Mao explains. Now, with "Freemartins," an attempt to slowly make his way back into the United States art scene, Mao's subject matter of race, sex, transience, and issues of fragmentation appears as the right entry point to do so. "It feels like it's this sort of, not full circle, maybe a half circle moment," the 52-year-old artist notes.

As our call nears the end, I ask Mao where he sees his art in the future. He states, "I want to push the work. I want to embrace the abstraction in the work. It's an impulse for me to rely on aestheticism. And I think that the type of work when you walk into a gallery, and you say, 'What the fuck is that on the floor?' and 'Why is this in a gallery?' That's the kind of abstraction that blows your mind. Like, 'What is this object?' and 'What does it mean to us? Why is it even here? How did it come to exist?'" There's a slight pause, "I want this stuff to get weirder and weirder."