Not because Garland presented herself as some kind of British Tony Robbins—she speaks in clipped sentences, has a dry sense of humor, and would surely shudder at the comparison—but because she has genuinely put the philosophy into practice, saying yes to every strange opportunity that has come her way and living an extraordinary life as a result.

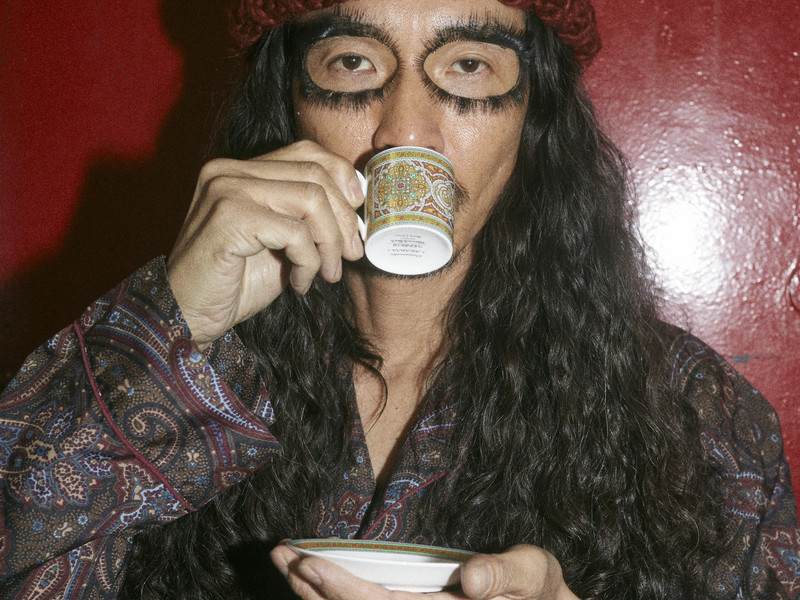

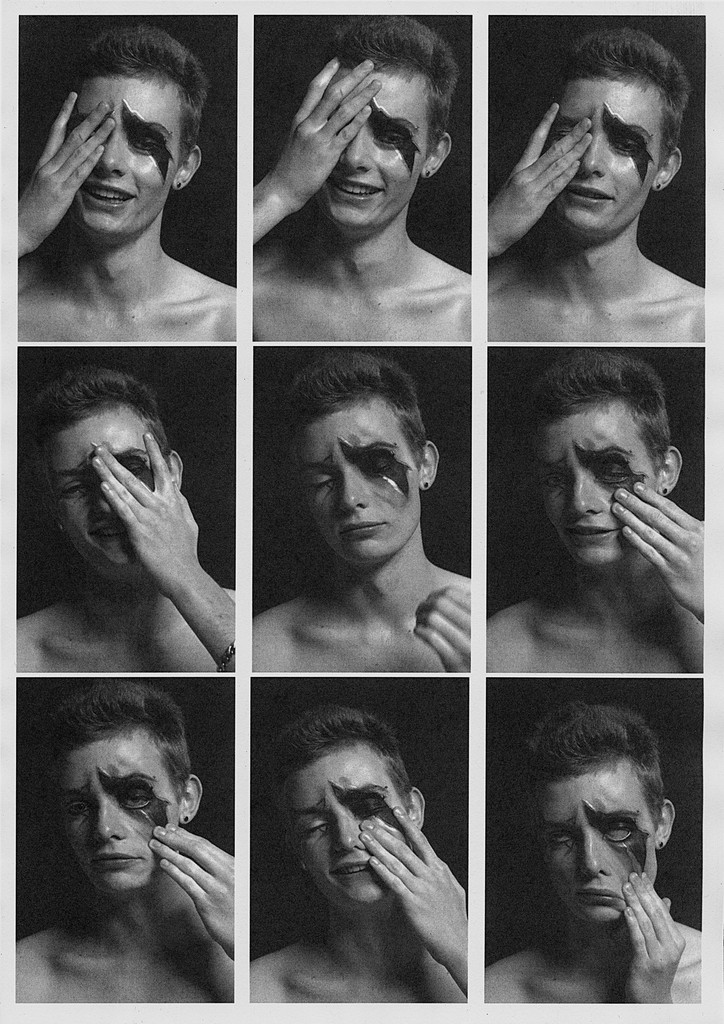

Garland grew up in the quiet English city of Bristol, dropped out of high school in the 1980s, became a hairdresser, moved to Australia on a whim, opened her own salons, filled in for makeup artists when asked, gave up hairdressing and moved to London (again on a whim), and became one of the most influential figures ever to grace the world of beauty. She specializes in the outlandish, creating alien creatures for the likes of (Lee) Alexander McQueen and Gareth Pugh, and transforming Lady Gaga for her famous horned “Born This Way” look. She has collaborated with every photographer on earth for every glossy imaginable—her personal favorite is the baroque “Good Kate, Bad Kate” cover of W, shot by Steven Klein, which won a National Magazine Award. Her book, Validated, a comprehensive portfolio of her work, came out in October.

Today Garland is the Global Director of L’Oréal Paris, but even with a larger platform and more responsibility than ever, she continues to do what she feels, and say what’s on her mind.

Your adolescence in Bristol coincided with amazing movements in art and culture, like the New Romantics. What are some of your biggest influences from that era?

I think you draw a lot from your past to inspire you. I was influenced by anything to do with the music industry, my porn was Debbie Harry, Toyah, Siouxsie Sioux, Lene Lovich, Annie Lennox, and I was obsessed by David Bowie and Leigh Bowery.

Your aesthetic is always artful and boundary-pushing. From where do you draw inspiration?

I think my brain is like a sponge. I just sort of lap up stuff to think about later. It could be anything, anywhere, things I see, I hear and feel. I could be in the potting shed in the garden rummaging through flower cuttings or equally inspired standing in front of a Ryan Hewett painting. It’s all about music and art, or indeed the very concept of our natural world.

What was it like dropping out of high school to become a hair stylist?

I’ve always been a risk taker. I think my mantra growing up has always been, What if? Why not? If it doesn’t work, pick yourself up and start again. You know, Build a bridge, get over it. That’s the sort of personality that I have. And so, when I was at school, I really wanted to go to university. I always thought I’d love to be a writer, or I’d love to be a journalist because I wanted to travel. I grew up in Bristol, and it was all very lovely and ordinary, girls grew up and they got married and they had children. I just thought, 'Oh, God, that’s so boring. I don’t want to do that. I want to have a career.' So I went to the careers office and I said, 'I want to go to university.' They basically said, 'Well, you don’t really have a hope in hell. You should just get yourself a job. Be an apprentice or something.' And I just thought, You know what? I think this whole system is wrong. You know, telling people that they can’t do something. Why not let them try? And then I was fifteen and I said, 'You know what? I’m leaving school. I’m going. I’m gone. I’m leaving.' So, I walked out of school.

My sister was a hairdresser. She was a very good hairdresser, and I always thought, 'Oh god, I don’t want to be a hairdresser.' But I was walking home, and I didn’t have a job, and I saw this advert in a hairdressing salon for an apprentice, so I thought, 'Well, I’ll start this and then I’ll look and see what other job I can get.' I went in there and I lied, I said, 'I’ve always wanted to be a hairdresser. My sister’s a hairdresser. Give me a job.' And so they did.

I did very well in the hairdressing salon. A year into my apprenticeship, I was doing what the seniors would be doing, except they were paying me an apprenticeship’s wage. I had a full column of clients and I thought, Well, this is easy. But I don’t think I want to do this. I don’t want to do this. I left and tried to become a computer programmer, because they said it was the 'job of the future.' I went through the training, but it was too boring, I couldn’t do it. I handed in my notice on the official first day. And then I went to work as a secretary, which was fine, but I was still bored. During that time I met my future husband and he said, 'You should go back to hairdressing.' And I was like, 'No, no, no.' But he knew these people who ran a really progressive salon, and we got on really well. They did lots of hairdressing shows. They paid by commission, so very quickly I was earning lots of money, traveling around the country doing seminars. Then I got married, and my husband wanted to go live in another country. I thought he was going to say France or New York, and he said, 'Let’s go to Australia.' And I was one of those people, I just said, 'Yes. Okay, let’s go. I’m a hairdresser. Let’s go.' And off we went.

What was Australia like?

Within fourteen months of being in Australia I had my first salon. I started off very small, it was just me and my clientele and gradually I would employ a person, would employ a person, would employ a person. I really loved hairdressing. I had a salon in Perth, I had a salon in Sydney. It was a well talked about salon, because we were very British and we didn’t do normal, boring things. You went there, you heard the latest music, you had the best coffee.

How did you transition into makeup?

I got bullied into being a makeup artist. I did this test shoot as a makeup artist, and I thought that the fashion people were so awful, and they were so mean to me. I was like, 'You know what? I’m gonna stick with running salons. I’m never, ever going to work in fashion.' And it’s hilarious, because here I am. On shoots, my photographer friends would always say, 'You should just do the makeup, Val. Do the makeup as well.' So, one day the makeup artist didn’t turn up, and the photographer said, 'C’mon Val, you’ve gotta do the makeup.' I only had what was in my makeup bag, what I really wore. It’s black for my eyes, red for my lips, and a very pale foundation. But I worked it out. And then those pictures went into a magazine, and then the magazine would ask for that photographer again, and they would ask for me, and then before long I got myself an agent. I had a friend who was in an agency and they said, 'Look, we can get you in.' I think I was just one of those people that was in the right place at the right time. Perhaps it was meant to be, because it fell into place. And then when I left Australia, I divorced my husband, sold the salon, threw a party and said, 'I will never do hair again. I’m going to London. I’m going to London to be a makeup artist.' And that was it, really. I got to London and just sort of worked my bottom off and crawled my way through.

As a makeup artist, you ended up creating looks for some all-time fashion shows. Tell me about the Alexander McQueen Spring 1999 show, where robots covered Shalom Harlow in spray paint.

It was a first-time experience with anything like that at the shows. So, none of us that were working on the show knew exactly how the robots were going to work, or what they were going to do, or how it would look on Shalom. You know, how the paint would spray. So, it was all kept very secret and in the dark. We all saw it for the first time at the show. You know the way the paint actually sprayed up and sort of went across her skin? I thought that was a beautiful moment. We were also working with Aimee Mullins, an Olympic athlete who had prosthetic legs. It was incredible to see the workmanship that had gone into these wooden legs — they were like wooden boots that Lee made for her. That was an amazing moment. Working with Lee was always exciting and incredibly emotional. But nothing could compare to the Harlow moment because nobody’d every seen anything like that before and it was so simple, and yet so profound and so memorable.

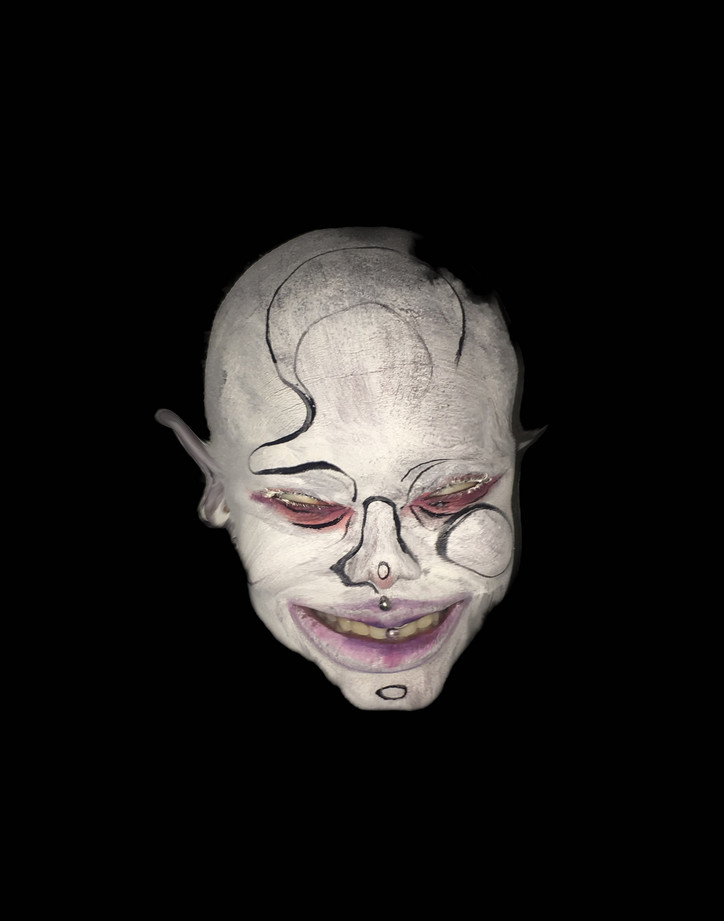

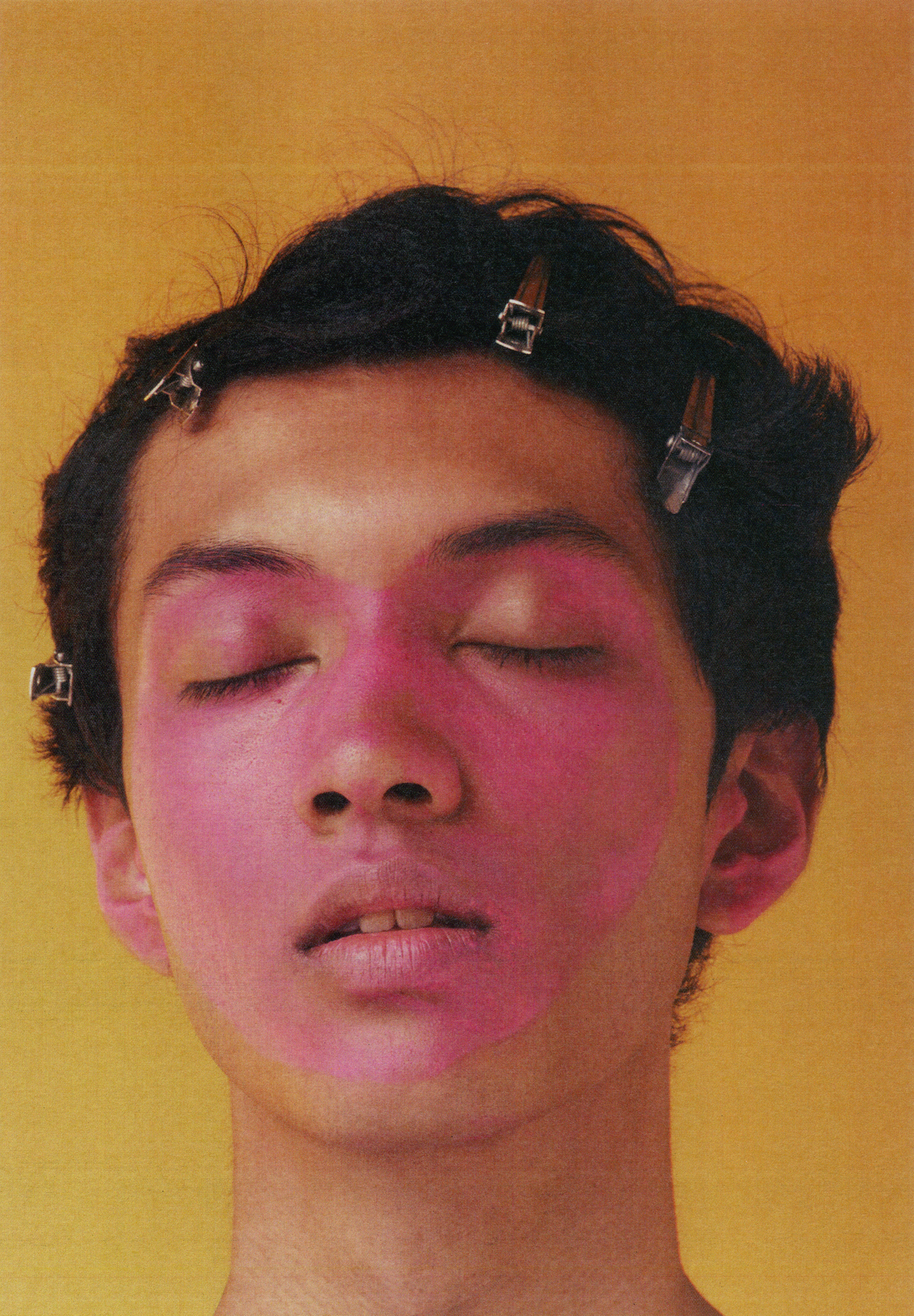

The beauty you created for McQueen Spring 2001, the Voss collection, was also incredible. The models were presented as futuristic mental patients — how did you conceptualize your approach for that?

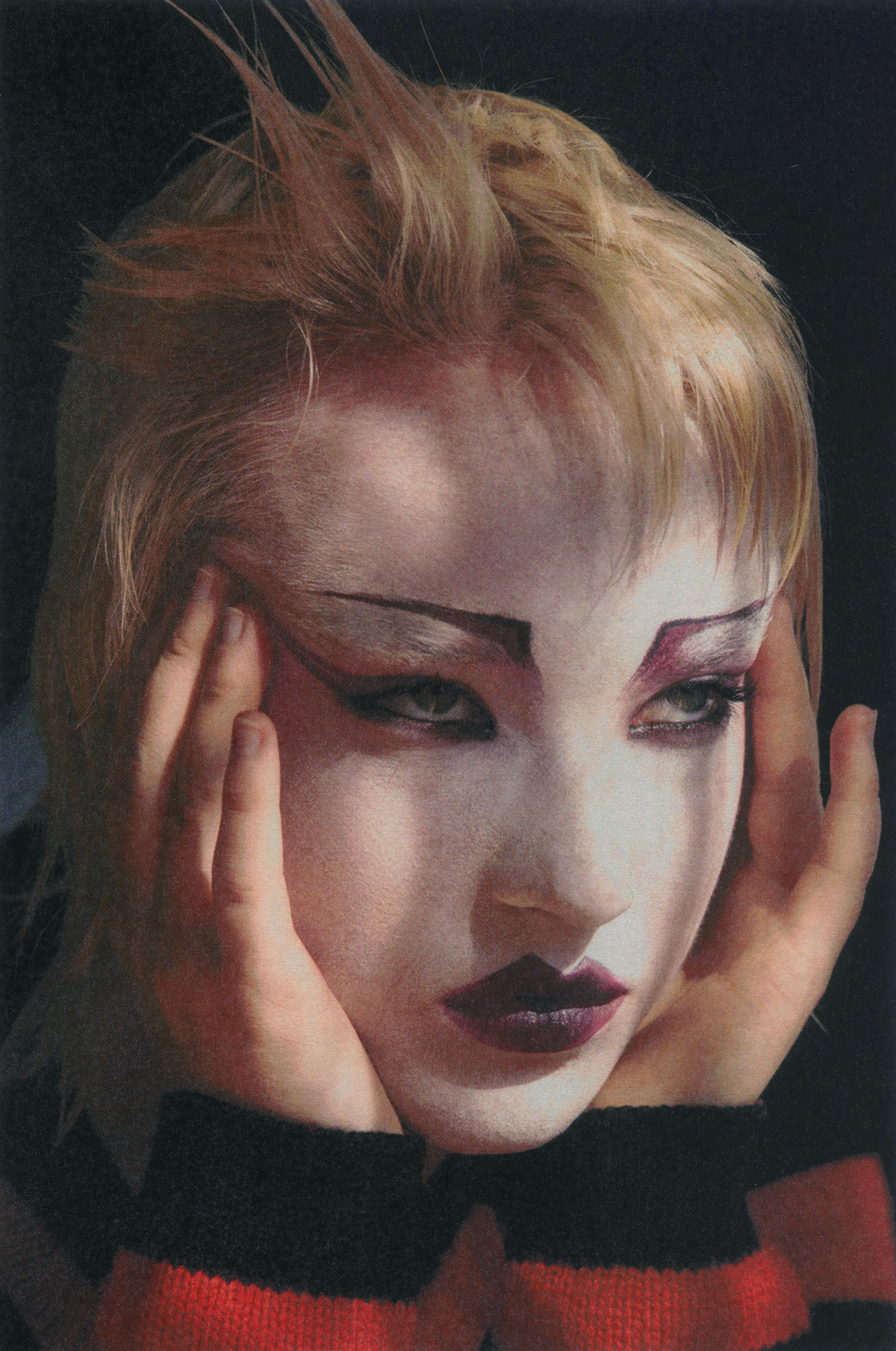

Lee always liked the extreme, and yet he always liked the skin to look more than just moisture on skin or a white face. He wanted it to feel hyperreal. AIs weren’t bandied about then as a concept, but he liked the idea of futurism. I called the makeup for the show 'Botox Beauty.' Botox was just beginning then, where people were just starting to get injectables. And I wanted to create this skin that looked like it was polished, airbrushed, slightly plasticized. It was perfect. Also, I wanted to make the girls feel like they were super-beings. So, I created this makeup that would bleach their eyebrows, and I used tape to stretch their eyes, pull their cheeks, pull their necks back. So, their faces were quite stretched, and then sort of in light and shade through the socket lines and eyes. We were highlighting and contouring then, but it wasn’t a trend. It was something that makeup artists would do, and have been doing for all time. So, then I sort of paled down the lips a little bit. I wanted them to look quite haunted and a little bit mad. It was like the girls were in an asylum box, and so I wanted there to be a tension about their skin. Another reason why I wanted to stretch the skin and then get this kind of rush of flush through the cheeks, is so that they would be kind of like, 'Oh, is she a little bit angry? Or is she a little bit excited?' She became a strange being.

Being in London in the ‘90s and early 2000s, with all these brilliant, creative people — the clubbing must have been fantastic. Do you have any stories from that era?

If you can remember it, you weren’t there.

'Validated' is out now.

Photo courtesy of the artist.