Gabrielle K. Brown: Holy Desire

Stay informed on our latest news!

While Frank envisioned the home as a place of rest and relaxation, Fassianos saw it as a space for work and creative production. Despite these differing philosophies, the two shared a belief in the natural flow of rooms and of people, a deep sensitivity to organic materials, and an affinity for soft, rounded forms. Their distinct styles converge in a vibrant, cross-cultural celebration of artistic legacy and everyday life.

Beneath the Same Sky will be on view at the Svenskt Tenn store on Strandvägen 5 in Stockholm and online from June 5 to August 27.

“At its core, ‘Nascent Flesh’ is about experimentation – placing process at the centre rather than the polished outcome,” NA Services says. That process involved inviting a select group of artists and fabricators to collaborate with Puche, and helping to explore unfamiliar materials and methods; pushing the work into new, more conceptually driven territory. “We were interested in how introducing materials outside his typical practice – yet ones we felt were adjacent – might influence his approach or inspire new directions.”

The exhibition is divided into two interdependent zones, each presenting a entirely different atmosphere. Entering the exhibition, one is immediately struck by a sense of hyper-reality as the sounds of low toned humming sounds echo throughout the space, suspended and anticipating its crescendo. The first zone is dominated by a monumental suspended sculpture by Tomy Ng, The piece evokes both organ and relic, system and specimen, with a bloated curvature and slick, yellowing synthetic skin that blurs the line between the biological and the mechanical.

“After a few early conversations, it became clear that Tomy was deeply engaged with the themes we were exploring in the exhibition.” NA Services explains. “He was also keen to step away from the fashion-focused world he usually operates in and create more sculptural, experimental work. This led to a collaboration between two artists working in parallel, both responding to the idea of nascenting – experimentation, evolution, and transformation through a distinctly sci-fi lens.” The sculpture is held in tension: an inflated form that hovers in mid-air, suspended just above head height and tethered by strings. It activates the surrounding space through a choreography of breath and pressure. The use of rubber and resin feels almost skin-like, responsive and sensitive to its environment, particularly to shifts in air pressure and surrounding materials. The soundtrack was made by Shanghai-based musician & sound designer, Gooooose.

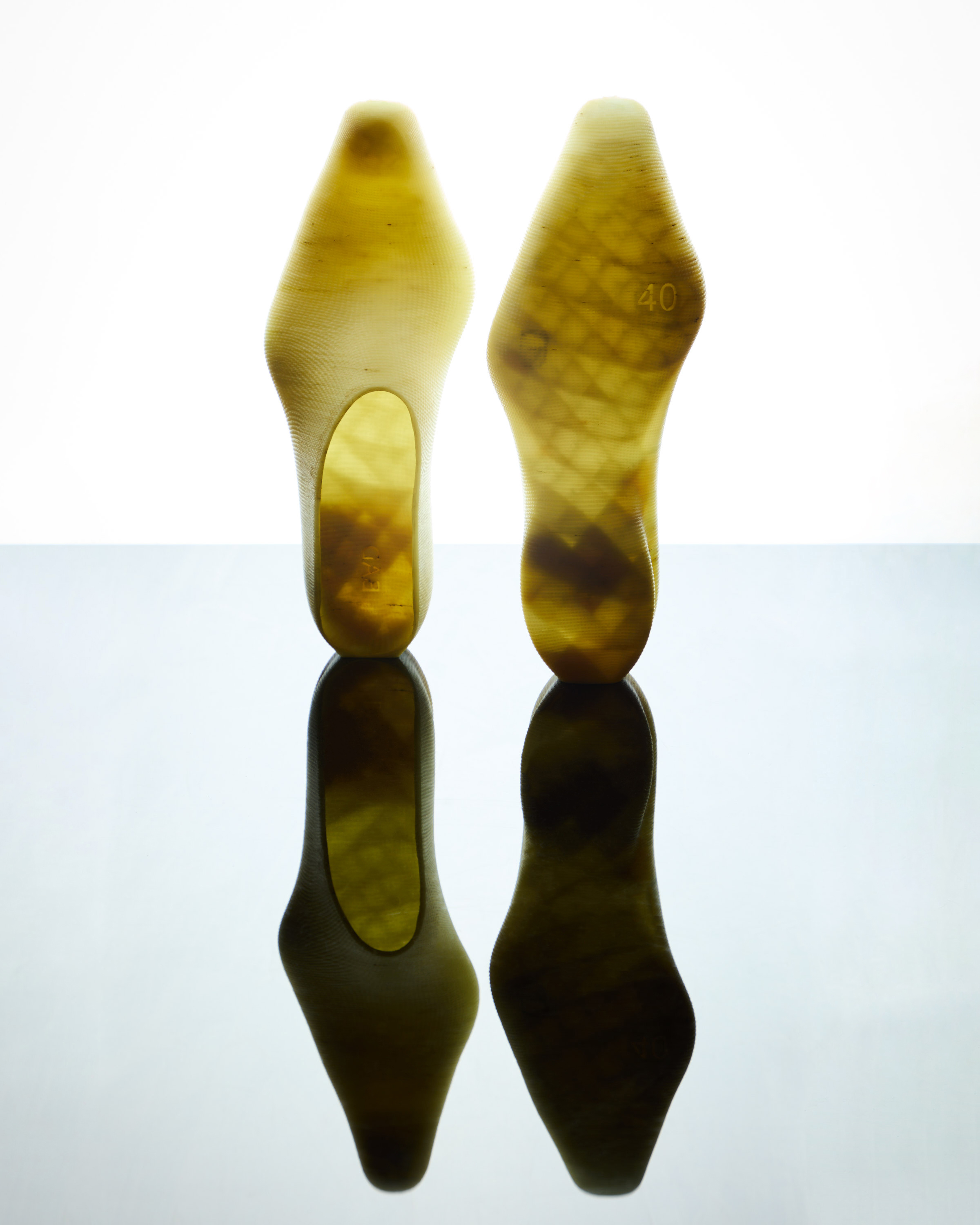

The material considerations are also central to the second part of the exhibition: a translucent chamber made with hanging sheets that diffuse light like a greenhouse. Inside and at the centre, a long table acts as a biomechanical altar, staging BAD’s shoe-objects, amongst experimental objects made of latex, faux fur, and tensile threads intertwine like sinew, or fungal mycelium, or the remnants of couture in the midst of decomposition. Some shoes float in water tanks. For Puche, his label BAD emerged from a frustration with architecture’s detachment from hands-on making. “What makes BAD special for me is the use of digital tools as a baseline and post-processing the results through rudimentary and traditional craft techniques such as dyeing, sanding and sewing,” he explains. Originally trained in architectural design, Mario’s work blends algorithmic modelling and 3D printing with tactile techniques rooted in personal history — his family once ran a traditional shoe factory.

“I like something that is originally perceived as glossy… that can then be altered to a point where imperfections become a key part of the object’s narrative,” he says. Nascent Flesh became a space for testing this dialectic; between digital and analog, precision and mistake, theory and emotion. “A lot of what was exhibited in ‘Nascent Flesh’ was about testing new tools and materials... I myself am curious how the practice will evolve.”

BAD’s work interrogates the very idea of the body, and how it can be amplified, distorted, or freed. “The pieces are meant to partially alter the perception of the body… they open up a conversation around what we consider normal.” What began as a literal engagement with prosthetic-like forms has become more subtle, but no less radical and confronting ideas of identity, dysphoria, and physical agency. While the exhibition’s formal innovation is undeniable, its real potency lies in its critical stance: a rejection of sterile, utopian futurism in favour of something messier and stranger.

For NA Services, this kind of work fills a crucial void in the London scene. Too often, the cross-pollination between art and fashion is flattened into marketable categories. What they are fostering instead is a dialogue, pulling young designers away from commercial constraints and back into raw experimentation. “We’ve always been influenced by the ‘anti’ ethos we see in people like Rei Kawakubo, Chris Ashworth, David Carson, Maison Martin Margiela,” they say. “Designers who completely redefined what a finished or beautiful object could mean... Their work showed us that the rough, the off-kilter, the things usually hidden — those can be the most powerful elements if treated with care. We’re not interested in perfection. We’re interested in work that carries feeling and risk.” ‘Nascent Flesh’ is not a vision of the future that’s sleek and sterile, but one that’s unfolding, and uncertain; a future born not from code or commerce, but from flesh, breath, and the will to evolve.

The Final Echo Isn’t A Sound will be on view at 545 W 23rd Street, Chelsea, from June 5 to June 21, 2025.