Ghosts Don't Walk In Staight Lines

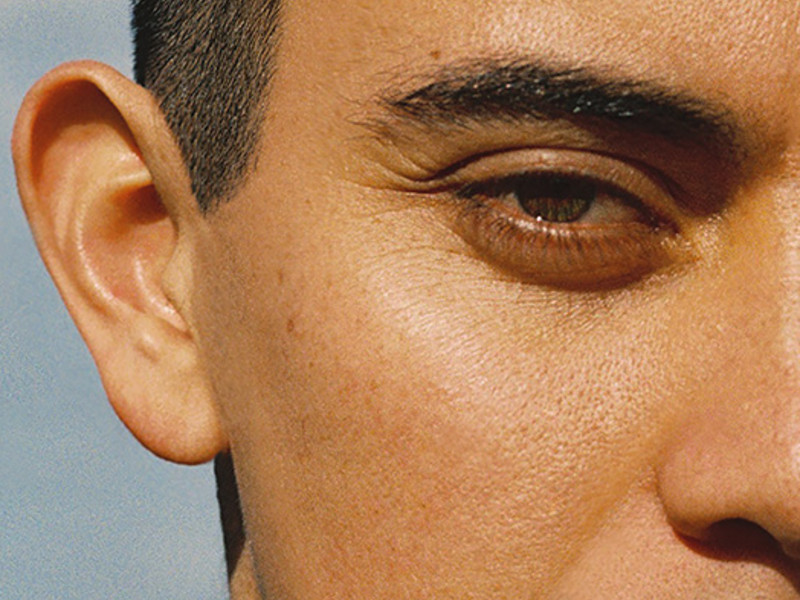

On view at Red Hook Labs this weekend, office sat down with de Brauw and van de Wijngaard; the duo sounds off on the project, below.

In three words, how does New York make you feel?

Saskia de Brauw: I would say New York has a sense of freedom, night and insanity.

Vincent van de Wijngaard: If I were to describe it in three words, it would be: I feel home.

As a foreigner myself, I can totally relate to the need to slow things down sometimes, especially when you live in a city that moves at such a high speed, like your exhibition references. So, how do you think the city’s pace affected the ways in which you interacted with your environment?

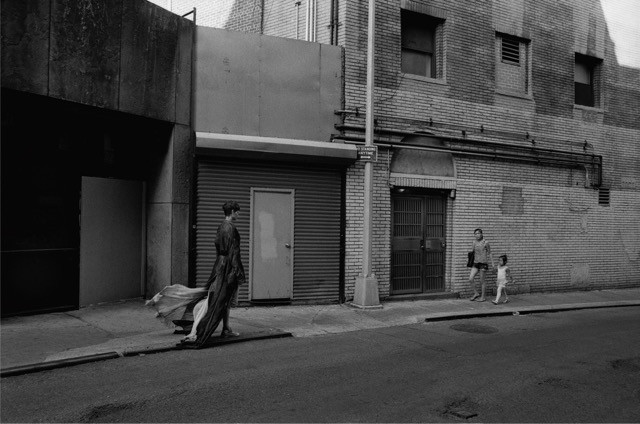

de Brauw: In New York, when you are doing something a little bit different, it’s not that strange, because many people here are doing different things. So, walking more slowly is not even that weird—it makes certain people really angry, but many don’t even realize they feel that way. I mean, there were parts of the route I walked that were really busy. So, I adapted my pace to the amount of people—the more people around, the slower I would walk. I didn’t consider myself as an obstruction and I never wanted to be in the way of people, and I felt that I was only once—in a very, very busy area around Times Square where someone pushed me and got really annoyed with my walking. But most of the time, I was able to be present and just move around. So, that’s something that’s definitely the case in New York—there’s space enough for everyone to have their own space, somehow.

Why did you start this project?

de Brauw: It was the moment before we moved to New York. When I was traveling a lot in the city with my work as a model, I found it quite hard to be here—the high pace was something I couldn’t really deal with. Then, these slow walks started to be an exercise for me to relax and be able to find my place in the city. After that, it kind of developed into this idea of, ‘What if I would do that for an entire day? How would that feel? And should I make a project out of this?’

What was the most surprising experience during your walk?

de Brauw: For me, it was when the experience of the walk at one point finally started to feel relaxing. Suddenly, I felt relaxed with what I was doing and my mind started to feel the same way. It’s the moment where you get a flow in your head—where everything kind of makes sense; it’s not busy with thoughts about what people might think or say, and the remarks just roll of you like water.

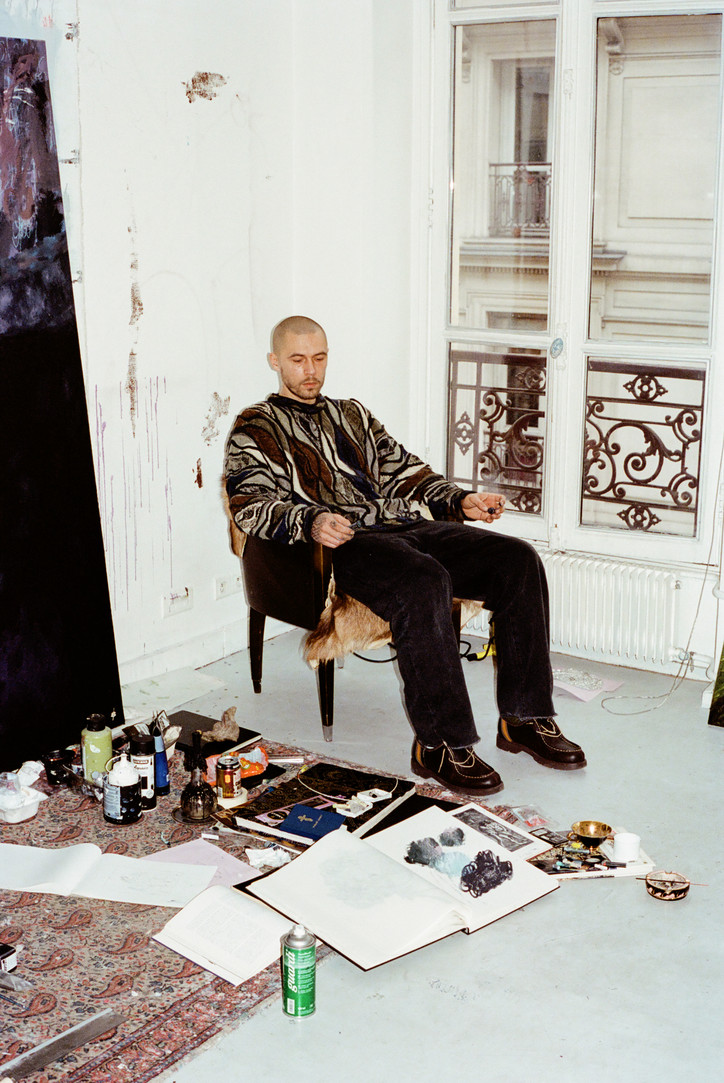

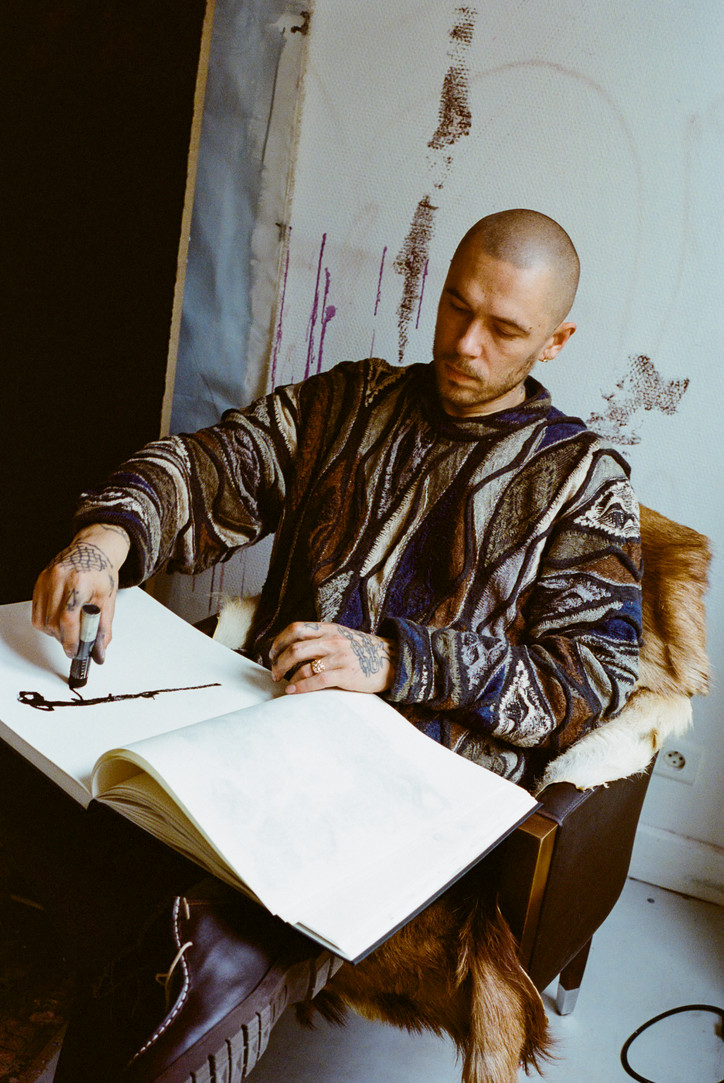

van de Wijngaard: Essentially, I am a photographer who works on the streets. So, the whole fashion aspect of it came a lot later. But I am someone who walks a lot on the streets, and there is hardly anything I enjoy as much as walking around with a camera and just looking at things that peak my interest for a moment. When I do get interested in something, I usually wander around a little bit more and investigate—that’s how we determined the certain routes that we followed in the film. But the walk is definitely the main subject—the film and photography are just evidence of it.

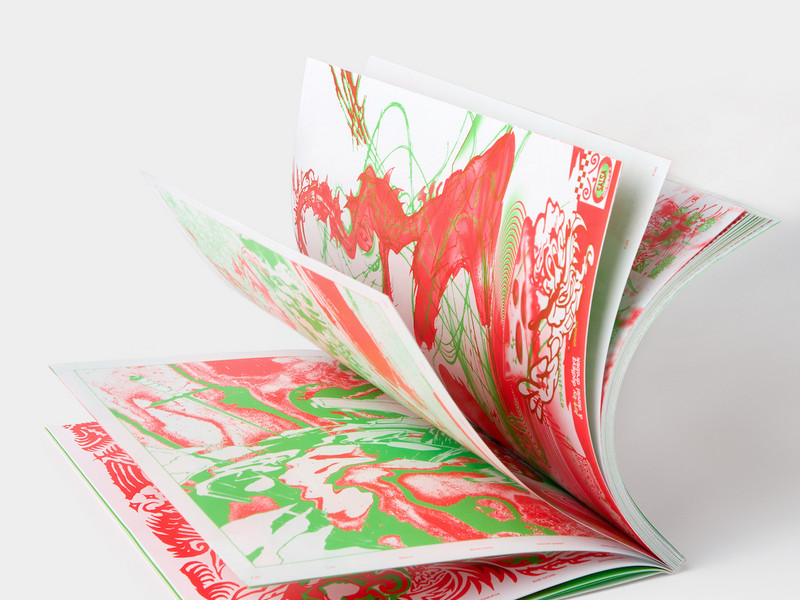

The project consists of the film, the exhibition and the book. Why did you choose those mediums?

van de Wijngaard: At one point, we sort of thought, ‘What would be the ideal way to document this walk?’ And of course, film is a good way to do it. So, the final film also includes a lot of Super 8 materials that function like flashbacks. Then we finally recorded and shot the final walk over a day, and those two were mixed in a chronological order. So, it’s almost like when Saskia passes a certain point on the road, there are these little inserts or breaks. Then we also had a lot of material that we had collected, like smaller interviews with people, and different quotes, and I had a lot of pictures. So, that’s when we thought we should maybe consider doing a book—that’s how it all came together.

You said you usually just find things or places that you like and wander around from there. But how did you decide on the actual route you took?

da Brauw: I just thought it was the most beautiful line that stretches from North to South—it basically takes us across the island that way. But for most of the route we follow Broadway, which is not a straight line on the grid. At one point, we do leave Broadway because we wanted to capture different neighborhoods and fields, and we really wanted to pass through Chinatown—so we do make a little detour. On our walk, we were avoiding the grid as much as possible, and tried to capture as many stories or interesting neighborhoods as we could.

What about the title Ghosts Don’t Walk In Straight Lines—what does it mean?

de Brauw: It refers to a street in Chinatown called Doyers Street, which is actually a small bended ally. There’s an old Chinese story that says that ghosts only move in straight lines. So, in this ally there where a lot of murders, but the bend in the ally happened to protect people from the ghosts of the people they murdered.

van de Wijngaard: It was more like, they had this alley with most extensive murders in the US, based in this little bend. The people committing those murders felt safe because they could never be seen by a ghost. So, there were these expanded network tunnels below the ground leading away from this little street, and some are still there today.

de Brauw: And our title is Ghosts Don’t Walk In Straight Lines, so the reference starts from there and includes a reference to the ghosts of the past, our memories, and the stories we all have—that everyone in the city does.

It’s 6AM, where in the city are you watching the sunrise?

de Brauw: Brooklyn.

What two totally normal things become really weird if you do them back to back?

de Brauw: In this case, the walking is something very normal, but when you change the pace of something that’s very normal, it can become quite strange. But it can be anything I think—that’s what performance art is really based on—doing something really normal but placing it in a different context, where it can become something strange.

Tell me about the Haider Ackermann dress in the film.

van de Wijngaard: We had this dress made for Saskia by Haider Ackermann, who we became friends with a couple of years ago while doing another short film. Haider designed the dress made of leftover pieces of textile which represent the patchwork of New York’s different neighborhoods. The idea we had for the dress was that it would be really interesting if we actually could see the change of time in the dress, by how much it was worn and through the changes that happened when it was used. So, Haider ended up making the dress from all these leftovers and because of the length of it, it takes the dust from the route, and little objects and other things you find on the surface of the streets, with it.

We also collaborated with musician Jim Beard. I have been a big fan of his for a really long time. He did this record that I really like that uses a lot of sounds from the streets, which was actually something that we were doing, as well. So, we were recording sounds for ourselves that we liked, and we wanted to have a beautiful soundscape supporting the film. We also worked with graphic designer Matt Watkins, whose book we had that we really loved. It’s a book by a filmmaker/photographer Will Wenders called Places, Strange and Quiet, and we just always went back to the book for inspiration because it’s so simple and minimalistic—we wanted our book to be very precise and clean.

What do you want the viewers to take away from the project?

de Brauw: Emotion.

van de Wijngaard: I think there are many layers to look at. You can look at the book, you can look at the people that we saw on our walk. For me, the pace which we move around—the high speed—is, in a way, really what it questions. Also, what all people hopefully will see is the diversity of it and the richness of it, just like if you were wandering around in the city, finding all these stories and seeing all these people, just looking at the scenery.

'Ghosts Don't Walk In Straight Lines' is on view at Red Hook Labs through November 11. Photos courtesy of the gallery.