Know Thy Selfie

Tell me about your work.

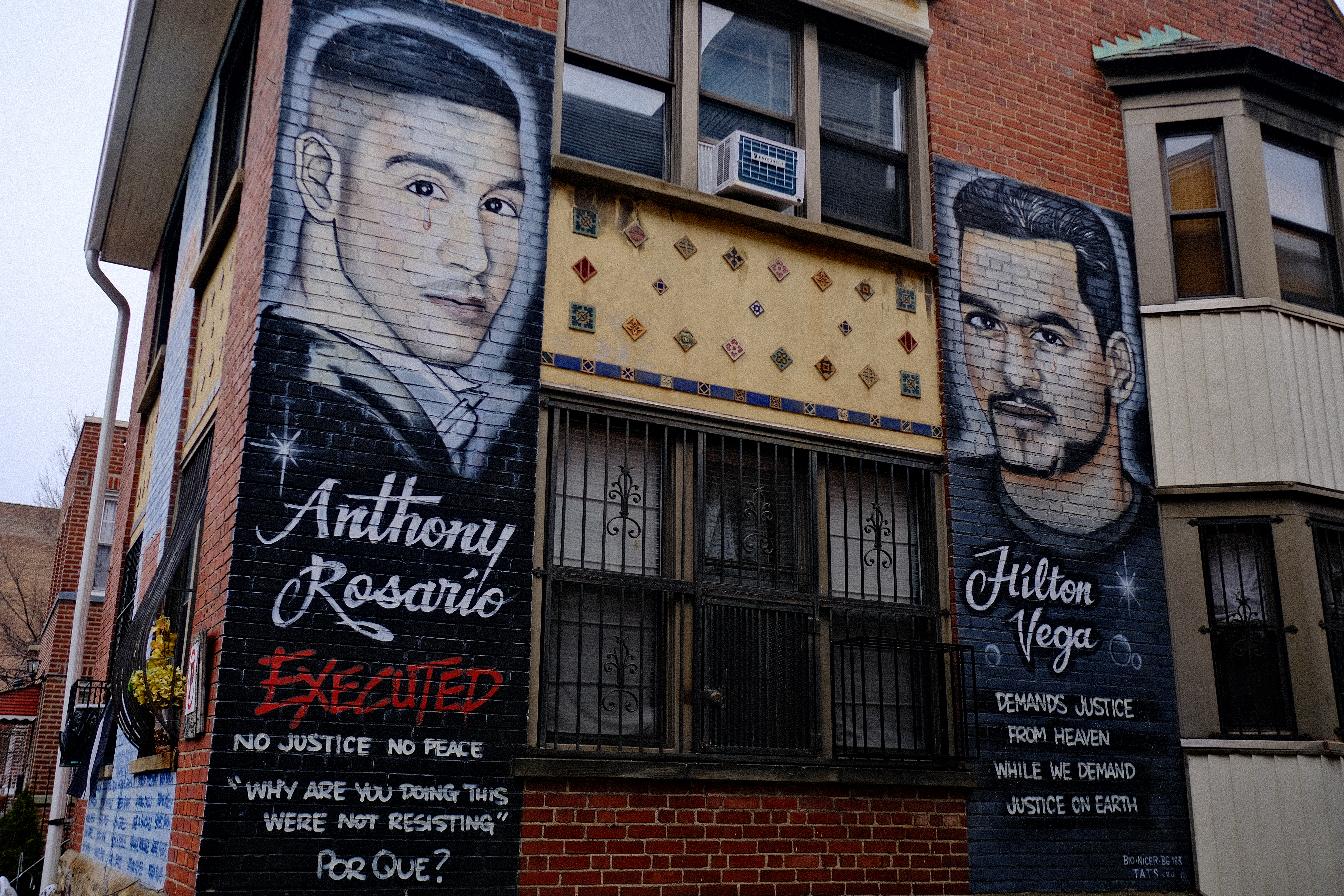

I was always very intrigued by LGBTQI in the U.S. being really successful as a movement, and being able to push through a lot of legislative change, and I was like, “Why is the women’s movement struggling so much?” They can’t really unify—not unify, that’s not the right word, but mobilize something tangible, or legislatively. So much of the women’s movement is about talking about intersectionality, and that idea has been around for about 30 years, where various women’s lib experiences, their level of oppression is based on race, class, socioeconomic status, country, religion, ableism, sexual orientation. But all those things exist equally in the LGBTQI community, and they somehow—I mean, I can’t say if they’ve adjusted perfectly, but they’ve been able to pick one issue, and push it through, and it changes the world and people’s minds. Of course, I try to understand intersectionality as much as I can as a white woman, but I do feel like there’s an immediate connection between women, just based on our commonality in identifying as women—with trans women too. So, there must be some things that are universal—like patriarchy.

Across cultures, religions, races—in every country in the world, there's patriarchy, and an inequality between men and women that's basically linked to toxic masculinity. And that's where the male gaze comes in. Obviously, the way I present my sexuality is very different from how a Muslim Pakistani woman would, for example, but even within the U.S. it gets quite complicated. So, I really wanted to explore that. What does it mean? Is it possible to view ourselves outside of the male gaze? Can you separate yourself? And what does it mean to be a woman? Of course, there’s space for a million types, but you’re either completely catering to the male gaze, you’re neutral, or you’re rebelling against it entirely, and is there a way to exist without that somehow influencing how you view yourself?

Your answers to those questions are obviously going to be very different than say, that Muslim Pakistani woman. So, how do you think your experiences as a white woman in America effected your work?

Most white women descend from what’s called 'the cult of domesticity,’ or ‘true womanhood.’ Growing up I was just like, 'Wait, what?' I mean, I had always thought that was what it meant to be a so-called lady, and a lot of it descends from Puritanical Protestant culture.

Oh God yes, it all goes back to that, doesn’t it?

Yeah. So, virtue is referred to as ‘true womanhood,’ and the four virtues are: piety, purity, submission and domesticity. So, even though I live in New York, and I’m an artist, there’s certain things that are just in my brain—even if I’m rejecting them, they’re still there. I mean, I'm from the Midwest.

Where did you grow up?

In a suburb of Chicago. Honestly, the Midwest is a culture unto itself, and I went to Northwestern so I didn’t leave until after college.

Right. So you were thinking about the male gaze—is that how you ended up with the selfie statues?

Totally. And I'd even say that a lot of it has become internalized—like an internalized male gaze. So, a lot of African American women would be combatting it but the way they represent themselves, celebrating their hair and their bodies, because for so many years they were taught to be ashamed of those things, and told that beauty is a European definition. But what they're doing is so different than what I would need to do, because that's not my experience—mine is something totally different. So, it's really not about me telling people what's wrong or right—it's me trying to get people to look at themselves and ask questions. Why am I doing this? Does this make me feel better or am I taking selfies for an audience?

So, for you, the selfie in the context of your art stems from self-analysis.

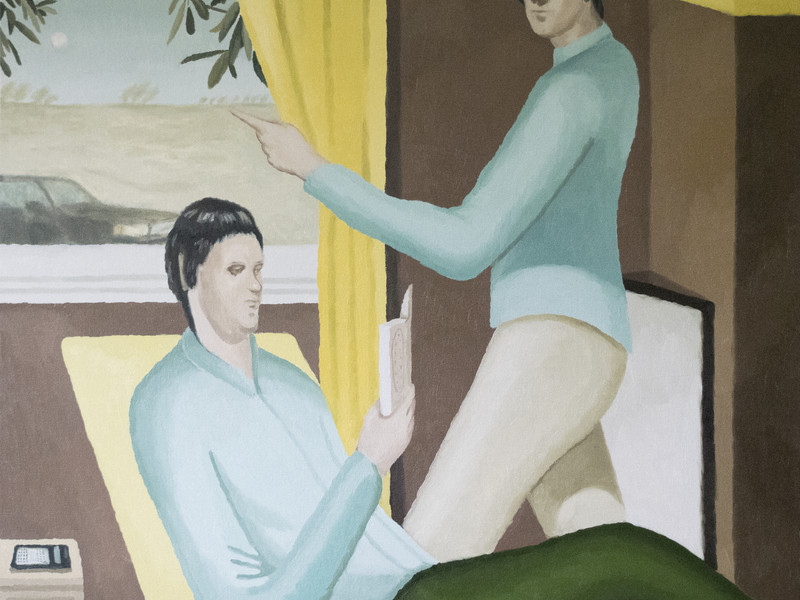

Exactly. Specifically the life-size sculptures, and the idea of having women from different ethnic backgrounds posing as a reference point.

Is all of your work specifically about women?

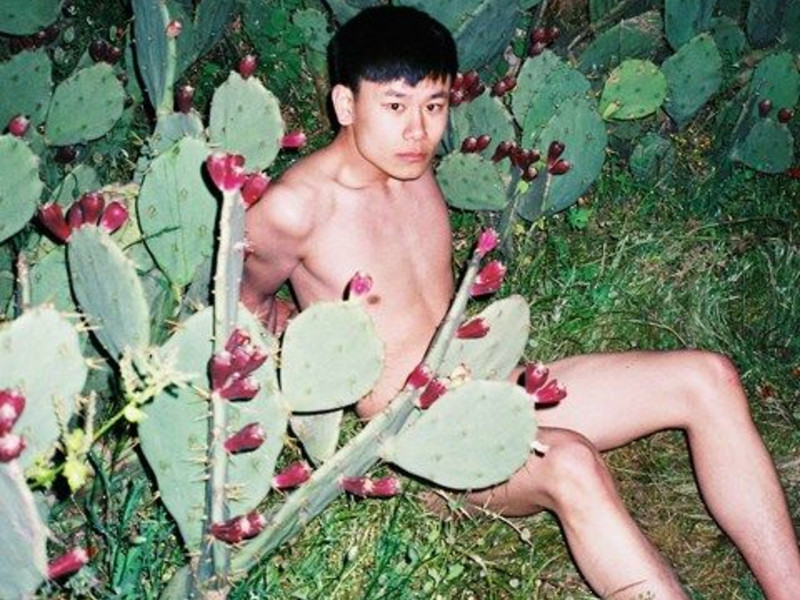

Not necessarily. It started off that way, and I definitely think trans women are a part of the conversation as well. But it's just about getting people to think about themselves differently, and their relationship to their bodies, and hair, and what have you. So, originally, it was all about people who identify as female, but towards the end I was like, 'Wait a minute, this is connected to toxic masculinity.' So, if I was to bring new themes on, I would definitely include men who bucked that trend in some way, because I do think that’s an important aspect of this conversation. I mean, we don’t all exist in a vacuum—we all have to move together a little bit as a society. But I do think that anyone who identifies as a woman, the only way for them to obtain power, even on a subversive level, is based on their appearance, and how many people find them beautiful—that's a constant message. Even those movements on social media, on one hand, can be really powerful. Like, thick eyebrows, unibrows, whatever are beautiful—but you’re still saying that beauty is the most important thing. We just put so much emphasis on these things to say that’s what’s relevant, and that if that’s what's considered beautiful, then you’ve achieved power.

Do you feel like social media is problematic in that way, or just an exacerbation of something that’s already going on in society? I always think of it as just an extension of everything that's already going on.

I think it’s a reflection of the collective unconscious. I’m not saying those movements are entirely bad, but I definitely think that everything has to be more nuanced, and more conversations need to be happening. Everything is not that simple. I definitely understand that need, or want, to be considered beautiful, but it’s very strange to me on social media because it’s not like, 'Oh, I can find a life partner, or someone will fall in love with me and I’ll fall in love with them.' Instead, it’s more like, 'Oh I need a fan club that considers me beautiful in order for me to be important and have power.' That, to me, is very bizarre. You would never hear a man say, 'Oh man, man-tits are sexy, saggy balls are sexy'—that’s not even a part of the conversation. So, I just try to reframe things, and if this is what one group is doing, and there’s another group saying that, how ridiculous does it all sound?

So, you’re work deals a lot with beauty, as well.

Right. And obviously I have long hair, and wear makeup, and I do those things because I enjoy them. It's not like I’m not trying to be super militant about things—I just wish there were more conversations about what's important beyond beauty, and unfortunately, I don’t see a ton of that on social media. In art, for centuries women have been captured by men, for other men, but through technology, women have gained authorship over their own images, and the way they’re represented. But how are we using that? How are we furthering the conversation? And is it enough? How can we be doing better, or doing more, or making it more nuanced?

How do you think women are doing that? How are they handling their authorship? Can you answer your own questions?

I think it’s enough that it’s confusing to me, because I don’t necessarily only follow redheads from the Midwest—I follow women from all over the world, and trans women, and trans men. That does sort of shift how I think of things on some level, but then I have to sit down and question what that means—for me and for them. It’s not for me to pass judgment on other people, like I said, people have different cultural legacies and I'm not going to be ethnocentric and judge another culture by my set of values. So, it’s not for me to say whether or not you should post something. Maybe that selfie is you celebrating your sexuality, and maybe that means something totally different to you. It’s really just about how people feel about themselves.

I always think of social media as a very edited version of yourself. You have so much control over how you present yourself, if you present yourself at all—sometimes it feels like you’re selling yourself, like a ‘brand.’

That’s definitely true, but I think it’s an echoing part of the collective unconscious, and that’s why I think it’s so fascinating. Part of the exhibition is these rotary phones dangling like a chandelier into the sculptures, because before, phones were literally used to disseminate information, like a phone tree—do you remember those? It’s something our moms did. But now, phones are really how you construct your identity. Even for children—who they’re friends with, and who they’re tagging—those are super complex things.

It's interesting when you think of the rotary phone. In terms of identity, with a phone back in the day, it was just your voice—now it’s your face. So, everything is all image. But back then, it had to do with your actual communication, as opposed to now, where everything is so non-verbal, and about beauty.

Maybe as Americans, once we’ve seen enough nudity, we’ll graduate to being like Europeans, and we won’t even care about it, you know? Europeans just have a totally different relationship with their bodies, and how they think of them, and even aging. I remember being on nude beaches in France and thinking, 'No way! There’s a whole family over there, and they’re just seeing each other naked and don't even care.' I mean, I’m not saying that all social media is bad—I just want people to challenge themselves more. Even for myself, with intersectional feminism—I think it's hugely important, and something we’ll probably continue to explore for the rest of my lifetime. It probably won’t be resolved anytime soon.

You mention intersectional feminism a lot. How does it play into your work?

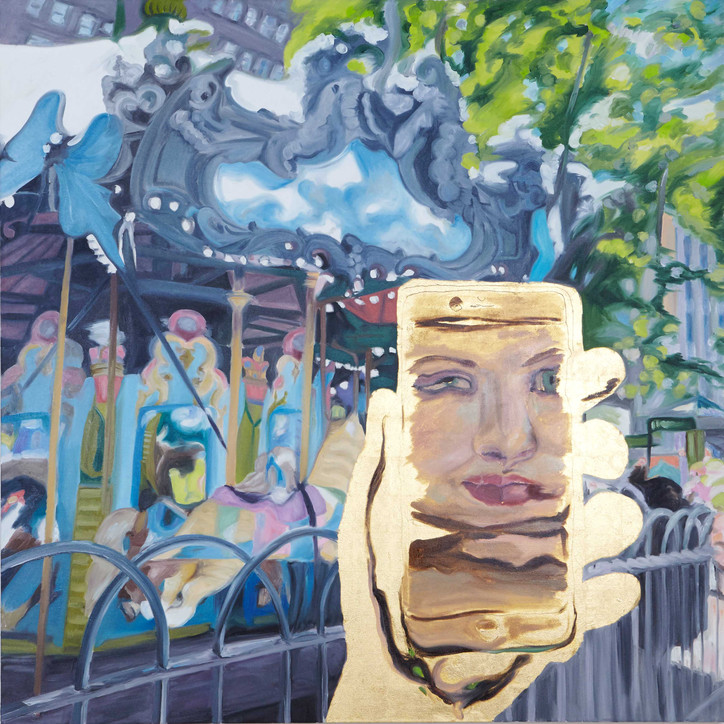

The paintings kind of relate, because I take photos of women’s reflections in the hand part of my sculptures. So, I’m looking over their shoulder with a cell phone camera and taking a photo of their reflections against different backdrops around New York. The reason I did that—or at least, my argument is that any image I post, or you post, or anyone around us posts, impacts this collective unconscious, and leaves this ephemeral imprint on some level. I think a lot about how these images are impacting other people—is this a responsible photo? I don’t know if there’s a wrong or right answer, but I always ask myself that question, and I think it’s something we should consider more. So, the paintings have the hands of the sculptures, and the reflection isn’t a perfect mirror image, so it's kind of like what you said—it’s a very edited version of ourselves, and if it’s so edited, we should be in control of making them more positive. I mean, I see so many kids on Instagram emulating adult behavior, and I don't know all of the answers, but I know we should at least be thinking about these things.

"Between Our Ears" will be on view at Garis & Hahn Gallery through October 20 in LA.

Photos courtesy of the artist and Garis Hahn Gallery.