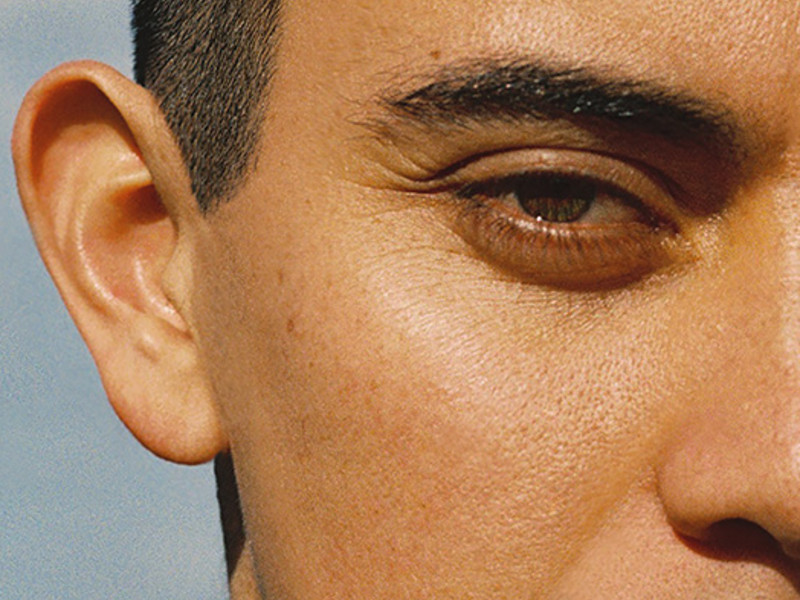

The Glorious Victory and New Power: Maxwell Alexandre

But how does one take a feeling, an unfamiliar place, or a fleeting moment in time and encapsulate it in its purest form? This is where the incomparable beauty of Alexandre’s work shines through. Through larger-than-life artworks created on crude kraft paper, now on display at The Shed, the artist is able to disrupt tradition and open minds to a tight-knit community characterized by resilience, strength, and comradery — introducing a new power.

Taking inspiration from the nostalgic pop culture references of his childhood, street skating culture, and the connections that shaped him, Alexandre displays the brilliance of his home and the Black experience as a whole through his current, extraordinary exhibition at New York's The Shed — his first ever North American solo exhibition.

How does your Brazilian heritage inherently find its way into your work? Did you always know you wanted to pave this path when you set out to create art?

In Brazil, and I believe in a large part of the world, the white person was the agent with the sovereign power to construct his own image, and also that of the “other.” My activity as an artist consists in disputing that place.

You were a professional in-line skater and served in the Brazilian military before you found your way to art. What led you on this artistic journey?

The fear of having a normal life — that is to say: studying, working, and forming a family was what led me to seek a life of adventure. That sounds quite dumb, I know. But my dream of being a soldier in the Brazilian Army was rooted in that fear. Just as wanting to be a character out of a video game — a black porcupine with futuristic skates (Shadow, from Sonic Adventure 2) — made me start street skating and leading an uncommon life, jumping stairs and sliding down railings around the city. That was my way of being in the world and seeing myself living that adventure from my childhood, the same one in the films, video games, comic books, mangas, and animes that I was consuming. That choice certainly sprang from an artistic drive to fuel my imagination and to create worlds that were impossible for a young black man like myself, from the favela.

Wanting to be different led to the choice of a sport that was unpredictable. Not even skateboarding was useful to me; my choice had to be more radical, and in this sense, nothing seemed more underground to me than street skating. Not only for its lack of a defined and affirmed industry or social group, but also because I had to rise above homophobia since skates were considered a “feminine” sport. All of these difficulties and contradictions that I had to face in light of an uncommon choice shaped me into the artist that I am today.

I see my relationship with photography, video, silkscreen printing, cataloging, and even curating as an inheritance from street skating culture, which, despite the lack of a market, managed to survive due to the impassioned dedication of its practitioners who were often active in these areas. It was on the academic path that I made contact with contemporary art for the first time, in a college course taught by painter Eduardo Berliner. That’s when I ratified that I was an artist. But actually, from my early interest in drawing comic books to doing the grinds I did as a street skater, that’s what I had always been.

Why did you make the intentional choice to create your work on brown kraft paper, or “papel pardo” and what are your connections to the unconventional materials employed in your work, such as hair relaxer and bitumen?

The pardo [brown, kraft] paper, the latex wall paint, the henna hair dye, the shoe polish, the Bitumen — all of this has a very strong coherence in creating the content of my work. But these materials were not chosen for their narrative coherence in my practice, but rather out of a question of necessity. I was beginning to paint and I did not have the economic means to work with anything else, in the sense of buying the proper materials like canvas, oil paint, or acrylics. I needed to think back and remember materials that were part of my life in a natural way. Henna is a hair relaxer that is part of the life experience of black women in the favela, such as my mother and sister. The shoe polish is what I used on my boots during my time in the Army. These materials were chosen for their pictorial potential, but above all, because they fit my budget. At that time, a bucket of latex paint cost 20 Brazilian reais and I would have enough paint for a whole year.

The brown kraft paper first caught my attention when I was producing in the fashion lab at college and I began to have daily contact with this material. There were many leftovers and scraps and I began to collect those papers, with great interest not only in the material itself but in the notes, drawings, and measurements that the students marked on them when making clothing patterns. Only later, long after accidentally developing the Pardo é Papel series, did I also perceive one of the important characteristics that this paper shaped in my attitude as a painter. Because, unlike canvas, information on paper is more definitive. You cannot make a lot of mistakes and you cannot construct dense layers. It’s hard to go back on paper. When working with paper you need to assume a specific behavior. This forces me to think and act quickly, otherwise the work tears, it gets destructured, or it breaks apart right in front of you. In this sense, I feel that the kraft paper puts me into a state like that of a stenographer, treating painting like notetaking.

This is your debut North American exhibition — what did you feel when you learned you’d be bringing your work to the United States?

When I observe the institutional spaces where I show my works, I generally restrain my thrill, as I am very aware of the artistic path I have tread, so these institutional events end up being more bureaucratic than a big celebration. My daily practice is religious. Everything I do is a form of worship. There is no hierarchy in what I present. Whether it is at MoMA, on the street, or in a room in my house, the delivery is sacred.

Why is it important to you to empower Black communities and honor important Black cultural figures through your work?

Being known as a painter is a very treasured thing for someone who comes from the favela. This is true for people from the favela who do not see this as a value, as well as for the elites who hold this trade in very high regard. I believe that this is the importance of my occupation in this game.

I believe that painting is, today, the most relevant medium. Sometimes I consider whether filmmaking could be this, but I always come back to painting, because aside from being very traditional, it is also very religious. Moreover, by its very nature, filmmaking is reproducible, which makes it more popular, while painting is a single, exclusive, and exclusionary object. If it is here, then it can’t be there. In the frenzy of the phenomenon of social networks, the value of painting has been conserved. It continues silent in an increasingly noisy world. People listen to what the painting is saying. It is inside a cellar of contemplation, a taught and learned behavior, that painting continues being affirmed as a codified, ethereal space of slow absorption for those with the privilege of aesthetic appreciation or the time of eternal leisure.

How did hip-hop culture and rap culture shape you, personally?

I believe that the greatest thing that rap could teach me is something that I already learned in my street skating days, which is to know how to walk on the street and to learn how to carry oneself.

Why did you decide to unite Pardo É Papel and New Power for the first time at The Shed? What strengths do these works possess when shown together, as opposed to separately?

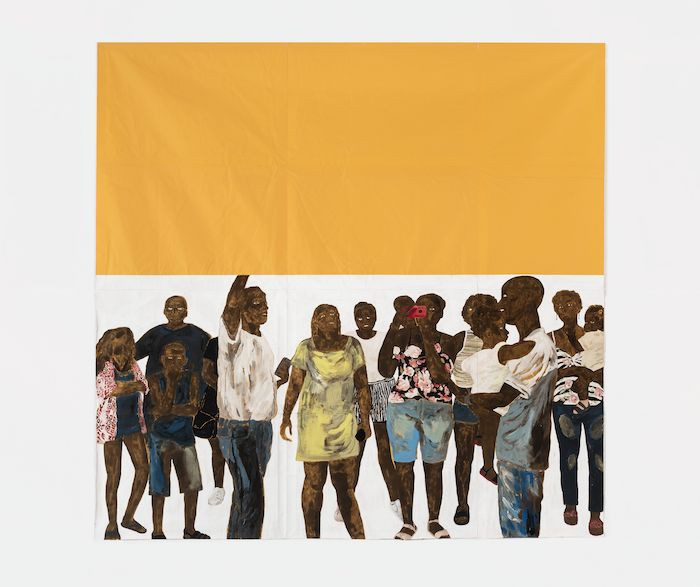

Since the beginning of the Pardo é Papel (The Glorious Victory) traveling show, I was adding at least one painting from New Power. Since this subseries had not been released yet, that was a way of introducing it within The Glorious Victory, the prologue to New Power. In The Glorious Victory, I paint the empowering of the black community through the ostentation of material goods such as cars, yachts, jewelry, and money, while also pointing to some professions of upward mobility for more melanated people, as is the case of music and soccer in Brazil. The Glorious Victory is also the period of my own rise as a visual artist, a new and unpredictable profession for a black person — especially one from a favela. Together with this, my exhibitions became relevant for managing to attract the public, from the urban outskirts to museums and galleries. This phenomenon was a prophecy in The Glorious Victory, which pointed to the narratives of New Power, where it is possible to see this community inhabiting white spaces dedicated to aesthetic appreciation and the maximum experience of privilege, which is subjectivity and abstraction.

New Power, therefore, is contemporary art for this group. The brown rectangles in the images of this series are a direct reference to the large banners of brown paper which are of the works shown in The Glorious Victory. The white in the background is a nod to the white cube — the galleries and museums — while the black characters evince a sense of belonging to and a very tranquil relationship with this new universe. This is the scenario that I paint in New Power, but which was previously invoked in the first period of Pardo é Papel, in The Glorious Victory.

That is to say, when New Power and The Glorious Victory come together face to face, sharing the same room at The Shed, the power of this conceptual mirroring acquires physicality. This exhibition is self-referent and is constantly mirroring itself. By seeing and physically attending the show, one becomes fully and personally aware of how the series is contained in the other.

What do you feel are the best ways to combat exclusivity in the art realm and what does New Power in action really mean to you? What would that future entail?

I believe in physical coexistence as the main way of fighting against this exclusion. Because the experience of art often ends up opening paths very far from the antiracist struggle, since such experience involves aesthetics and conventional beauty and thus results in a romantic notion — a fetish concerning black people. This explains why someone would buy a painting with a black character as the subject and hang it on their living room wall, even when in another context they cross the street to avoid meeting up with a black person coming their way, as they “feel afraid” of meeting a black person on the street.

You can paint every day about the favela and the life experience here, but on the opening day, the audience is going to be white. This is perturbing. You look to one side and see that the black people who are there are invisible, working as cleaners and servers, while the others around are smiling and congratulating you for a painting where the black person is represented bidimensionally, in flat colors. There, in the painting, the figure does not talk, does not make demands, does not problematize — it becomes a piece of a portrayed reality, nothing more. Having one of these paintings in the living room is easier, and seems to be enough for a person to avoid actually living together with reality.

I think that the approximation with truly peripheral poetics allows for the appreciation of my work in a more real sphere. When the Pardo é Papel exhibition came to the Museum of Art of Rio (MAR) here in Rio de Janeiro, I witnessed something similar to what I speculate about in the New Power paintings. On that day, the museum was black — not only in the art, but in the space itself. And the visitors shared a feeling of belonging. This is also an important point because it is not a mere question of inviting, appearing, and being present — it is about belonging. During this period, I heard the report of an artist with more than 20 years of experience in the art scene, very well-established, talking about how he had never seen an audience like that in a museum. New Power represents and reinforces what is traditional, while it feeds what I consider the greatest of privileges: contemporary art. In it, I aim to invoke the presence of melanated people with awareness inside the galleries and museums, the established — and elitist — spaces.

Pardo é Papel: The Glorious Victory and New Power are on view at The Shed until January 8th, 2023.