Goodnight Sweet Thing

Robert Greene, the author of The 48 Laws of Power once said that power is an invisible realm that envelopes society, where people continually battle each other though no one is trained to talk about it. Only when you make mistakes do you realize how political people are.

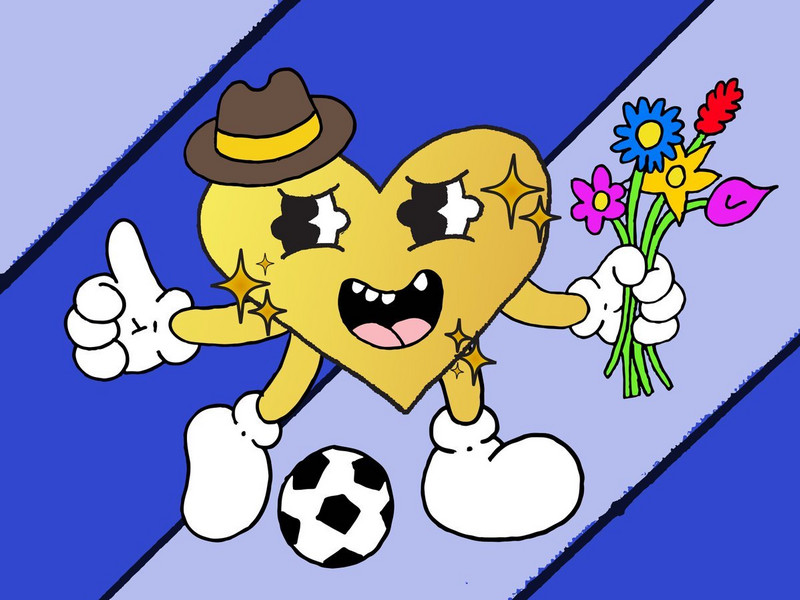

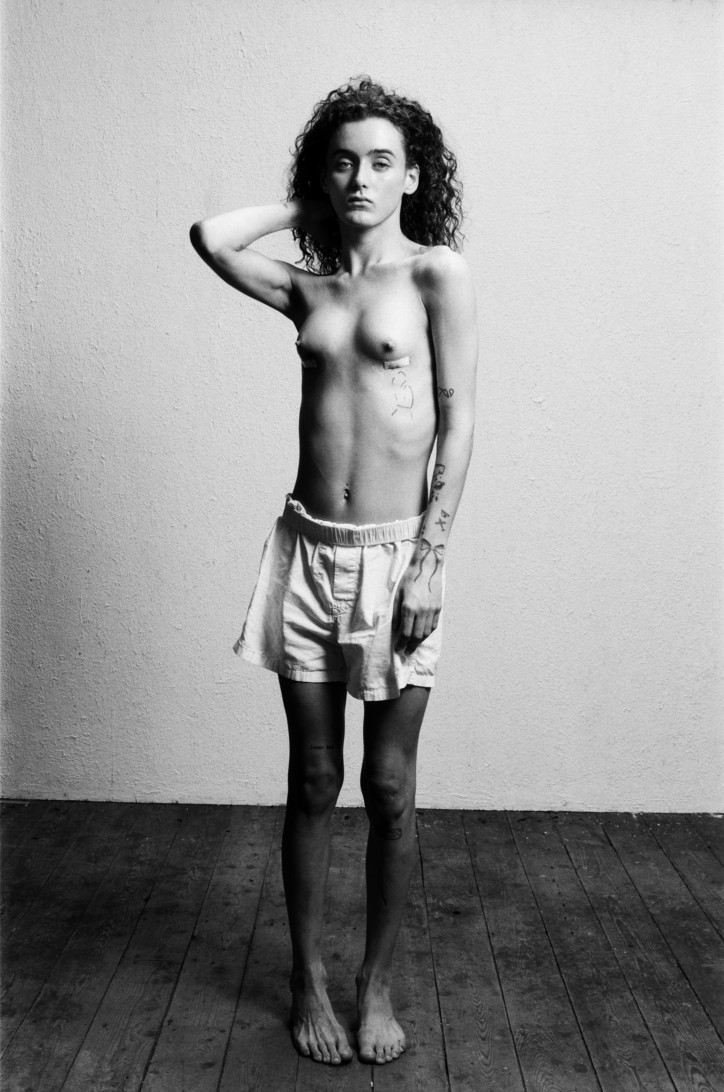

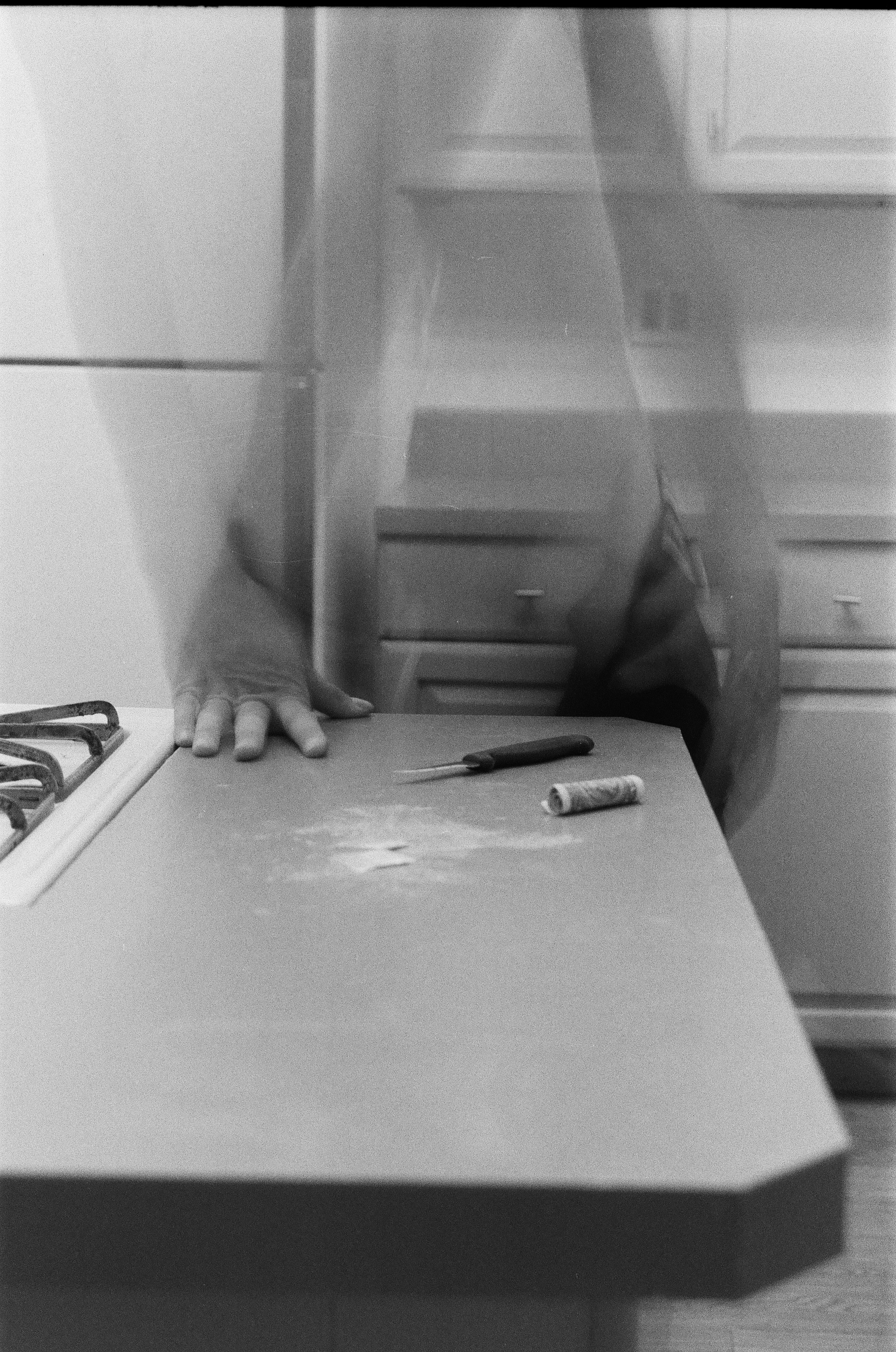

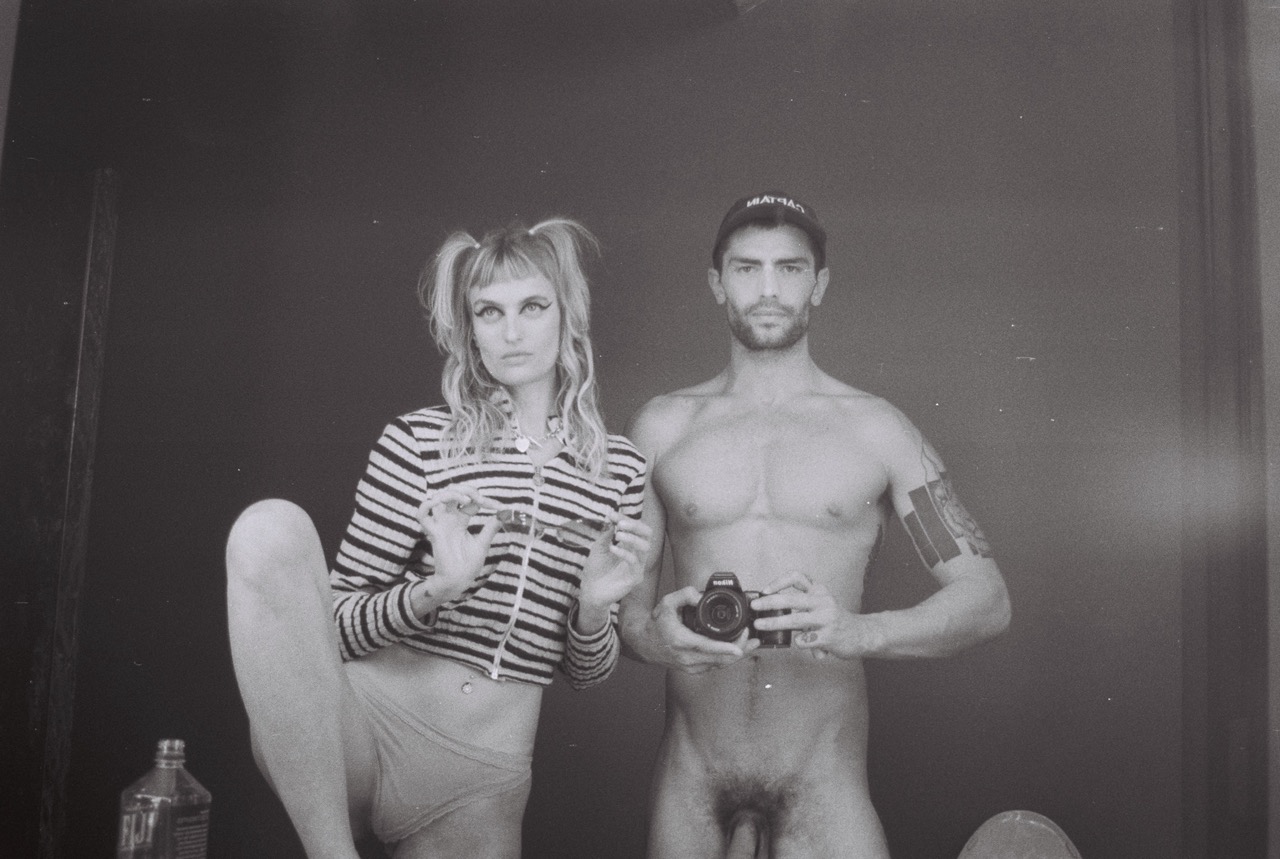

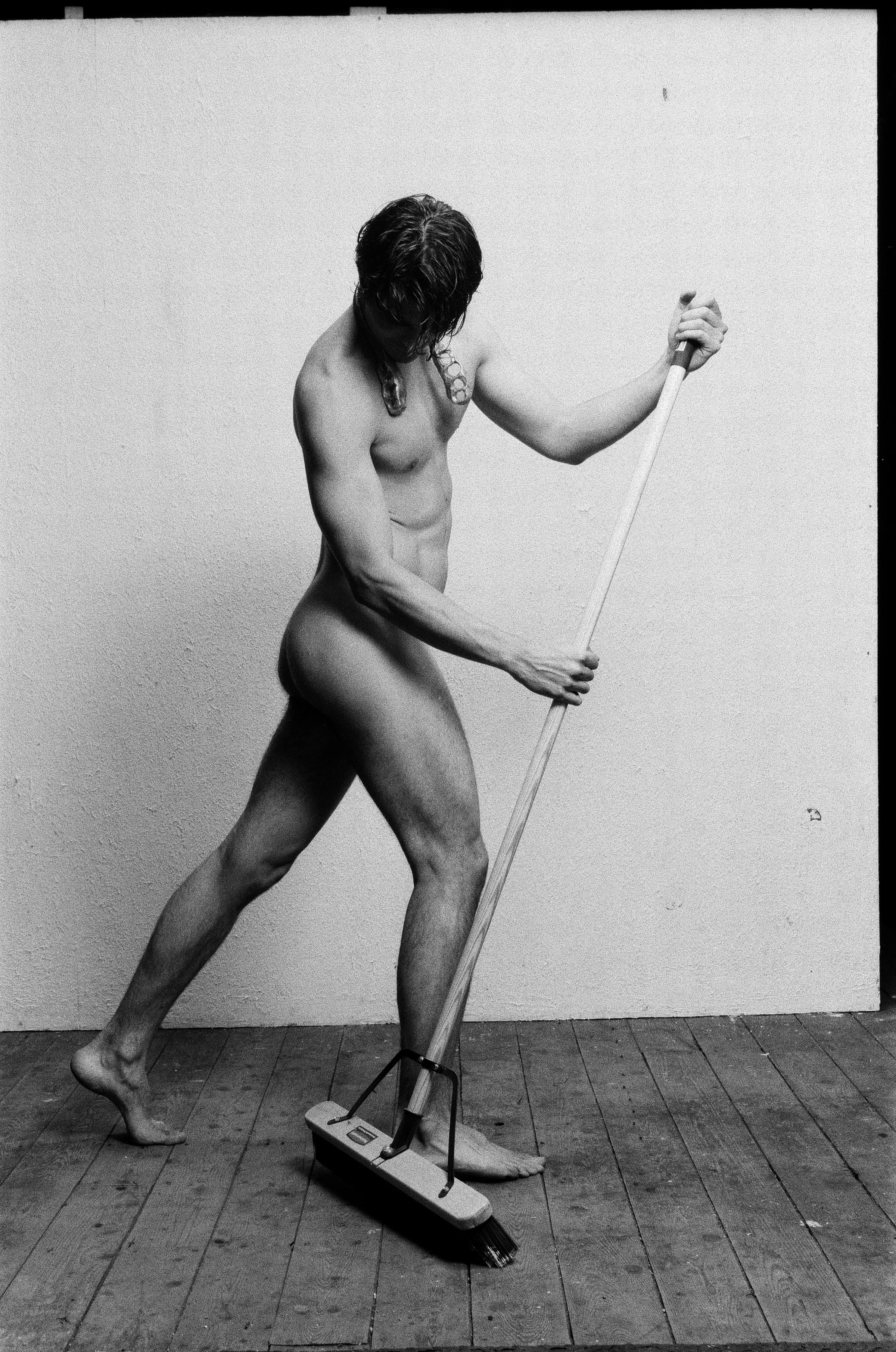

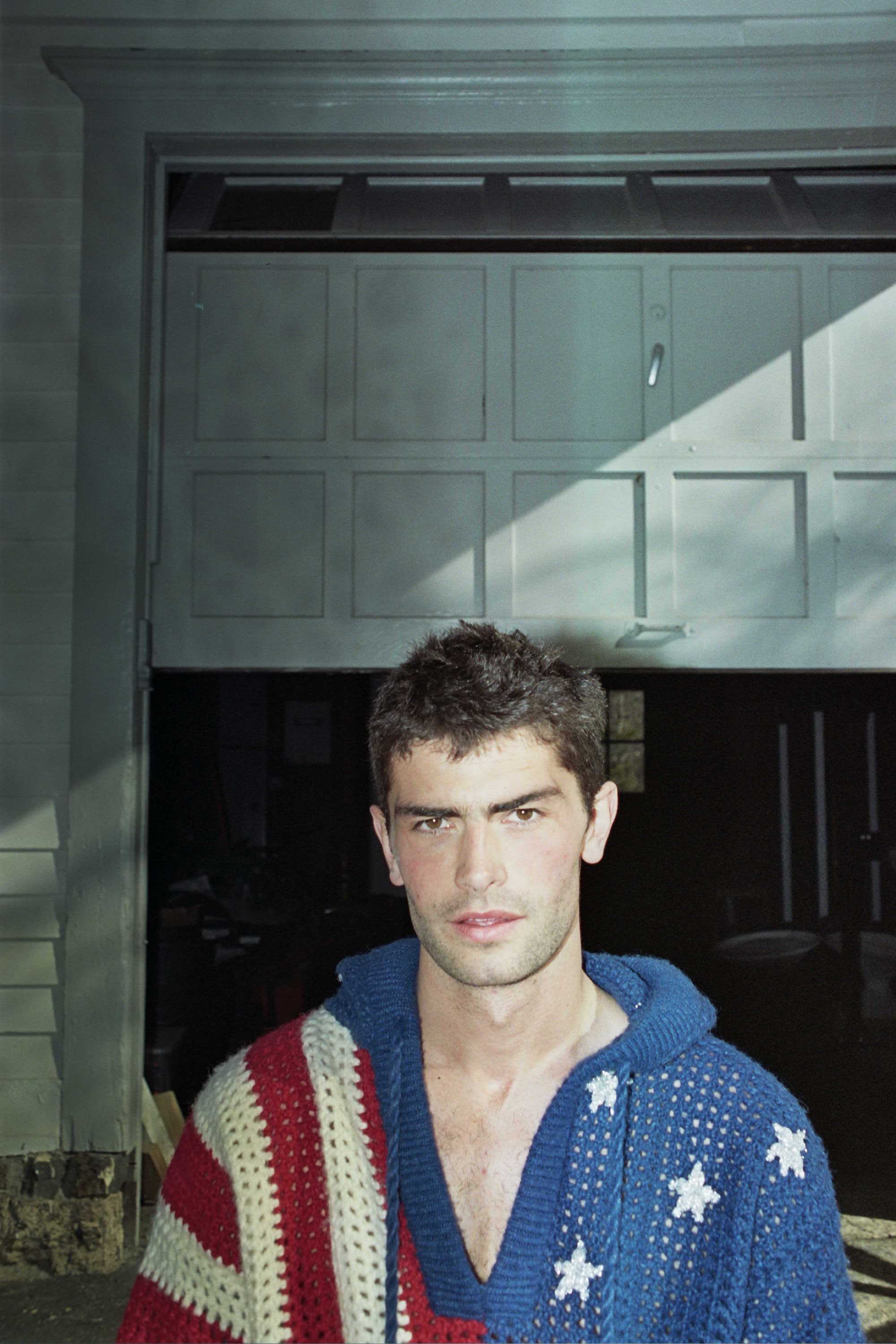

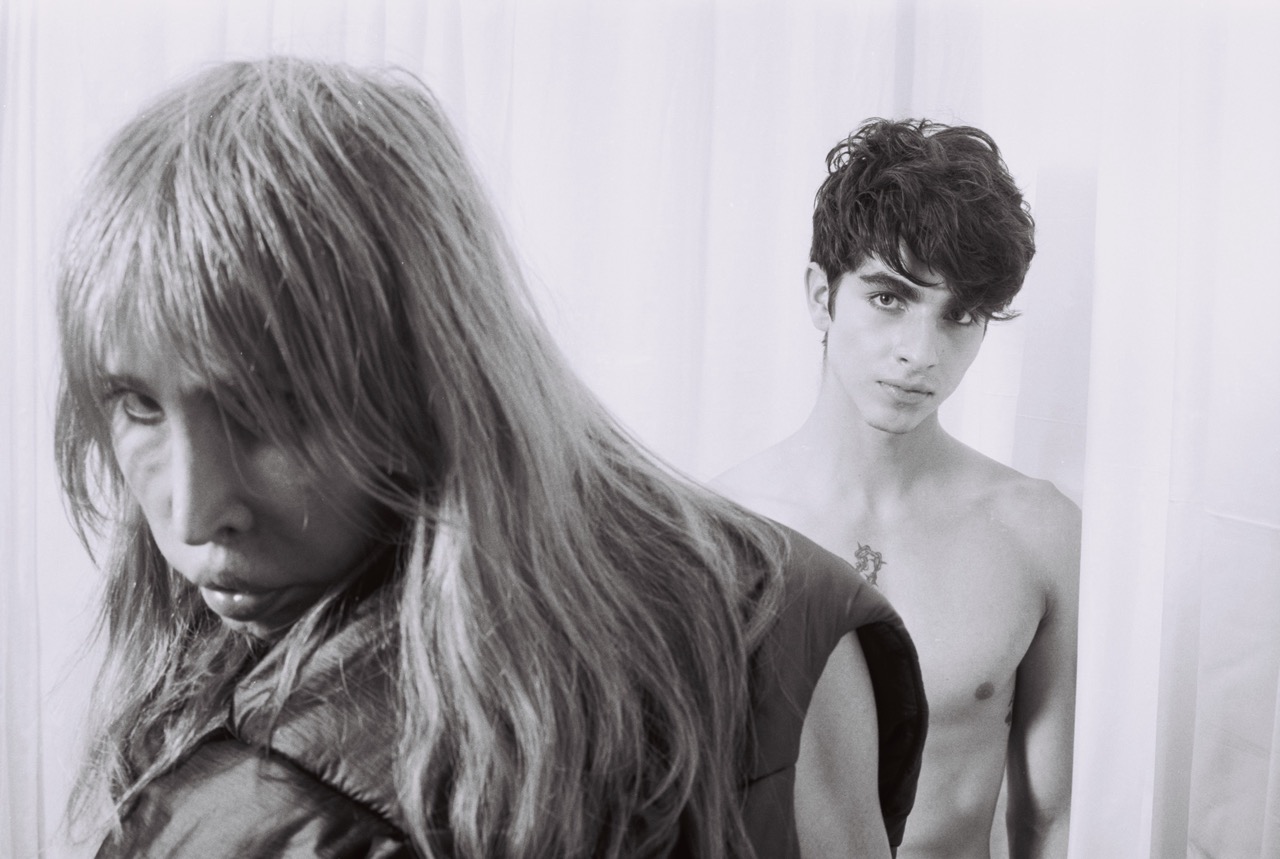

The rules of the game are simple, a referee in a fetish mask (Joshua Weidenmiller) exclaims to the crowd. Please. Don’t. Hurt. Me. Borrowing lines from Brache’s poems, the actors’ fragmented dialogues are a jarring display of cognitive dissonance in a three tableau narrative involving sports, the psyche, and polite society. The opponents, named Nothing Girl and Mary Magdalene, face each other in front of the nation’s flag, topping each other from the bottom, moving in-sync, writhing in a pool of red gelatin. The audience laughs, not knowing what to expect next. In the second scene, Josh plays an analyst examining Betsey in a lounge chair, an element of Jungian and Freudian influence on the night’s inquiries. Among those inquiries, the show’s co-directors probe into America’s obsession with the masking of oneself in order to survive and exist in reality; the juxtaposition of constraint and consequence deeply embedded in our daily roles.

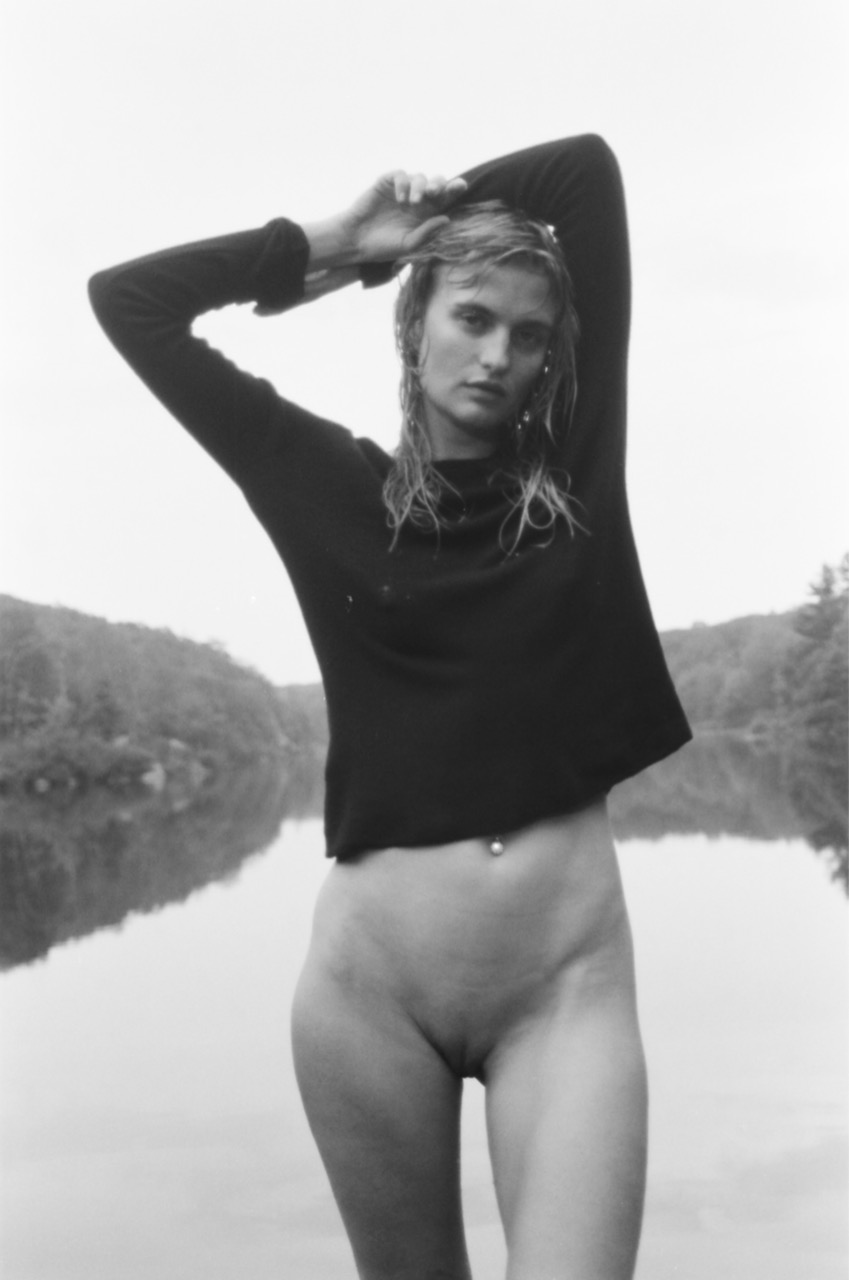

“Sports mirror the facade of contemporary life,” Sigrid describes her and Brache’s vision for the evening, or poetry in motion, as she calls it. “We’re expected to perform, constantly pitted against one another within the capitalist machine under the scrutiny of a faceless judge.” One summary of the show could be more or less a marriage of central ideas revolving around interdependence, the unconscious, and PsychologyToday.com.

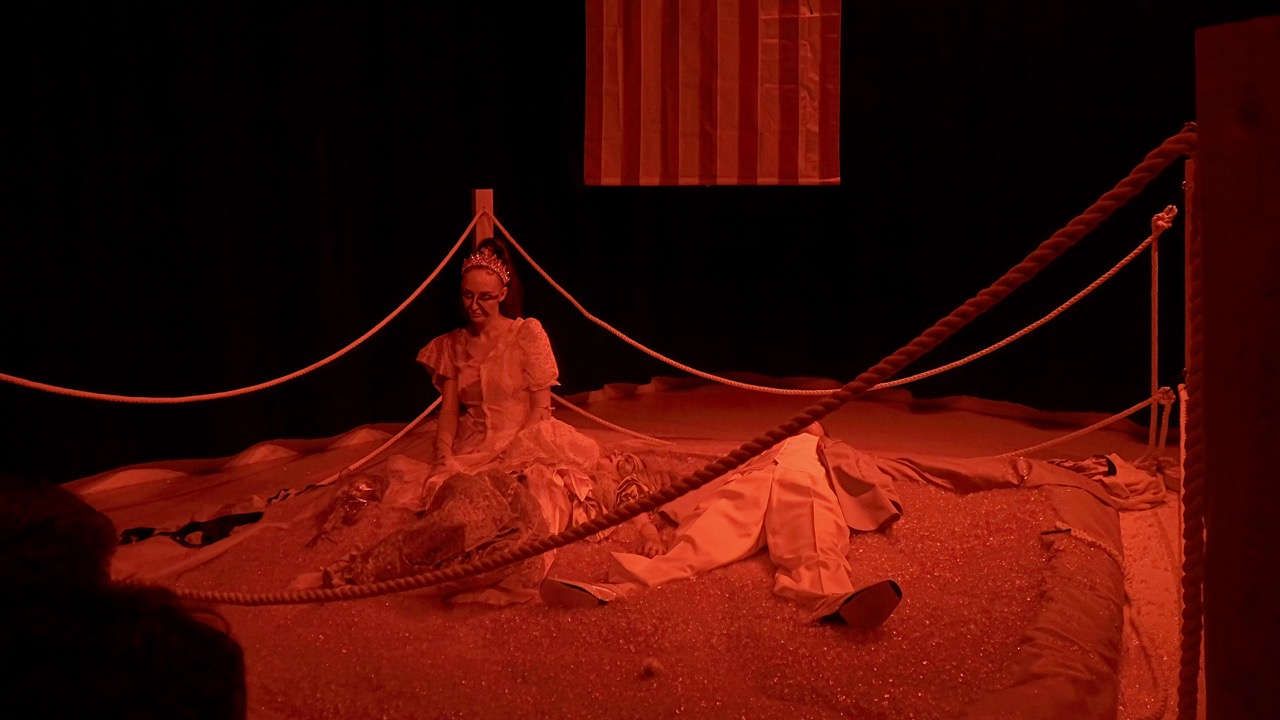

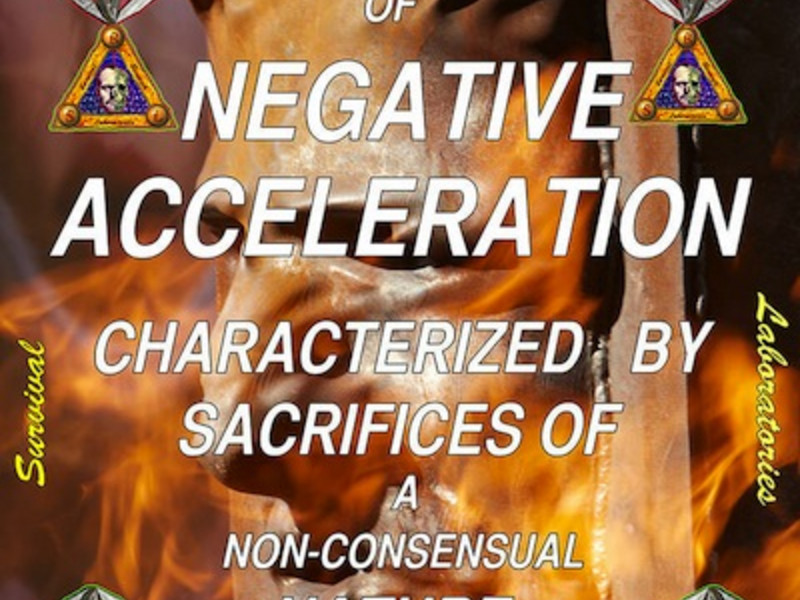

The third act ends with a play off of a prom scene, a celebratory tradition rooted in gendered competition and peer judgments. It would make sense that the use of Jell-O also holds origins as a 20th century symbol of another American invention—specifically aspic, molded vessels that once encapsulated long hours of domestic female labor as privileged entertainment. Inspired by the fetish magazine Blushes, Brache’s book cover depicts an AI-generated image of a mannequin-like woman with a man pouring water over her legs, imbued with an idyllic quality aesthetically referencing JCPenney catalogs from the ‘80s and conventional (or otherwise sanitized) notions of beauty.

Victorian era music plays in the background. Nothing Girl pushes Mary forward, who prays on her backside. Why does being sick last so long? She screams. “She’s sick because she’s staring at her reflection,” explains Sigrid. “She’s sick because she is using others, because she has to work too much, or maybe, because the machine is sick."