Holy Fools

Unlike Bruce Nauman’s 'Clown Torture,' as part of his retrospective, Disappearing Acts on view at MoMA and MoMA PS1, which contains multiple scenes that play on loop simultaneously, and which provided a framework for this piece, Viñao’s clowns each have individual, intimate stories to tell, each story building on itself to create a miniature saga—the screens are mounted back-to-back, each with its own pair of headphones, and the second chapter of each scene lies directly behind the first: a small change in staging or movement reiterates a faraway point, which builds a mesmerizing riddle. The show is like a labyrinth of Sphinxes singing their riddles, exploring the edges of expression. The intimacy is implicating: the viewer is participating in this self-inflicted torture, unable to tear our eyes away.

The fact that these are clowns lends an opportunity for silliness that is not lost on Viñao, or her performers. Silliness can quickly devolve into maddening absurdity, and the show vacillates between these two impulses with subtle expertise. The final video—the only clown who is given a third saga, and who’s opening monologue, repeated on loop in a church, is like a lyric poem by a Southern belle version of Lolita—is such a simple performance steeped in metaphor it feels like an encapsulation of not only the show, but of art itself: the clown steps endlessly through a door that rests in a frame, as you would find in a hardware store, one that essentially goes nowhere. She goes through a range of intense emotions, the overall effect being that going through this door leading nowhere is incredibly difficult, a struggle that goes on, essentially, forever.

I met Ondine Viñao, the author of this delightfully demented saga, on a cold, windy day at a coffee shop on the Lower East Side. She was perky and lithe, and we commiserated about the recent antarctic temperatures in New York before retiring to the basement to discuss her piece, what it took to bring it together and the clever timing to coincide with the Bruce Nauman retrospective.

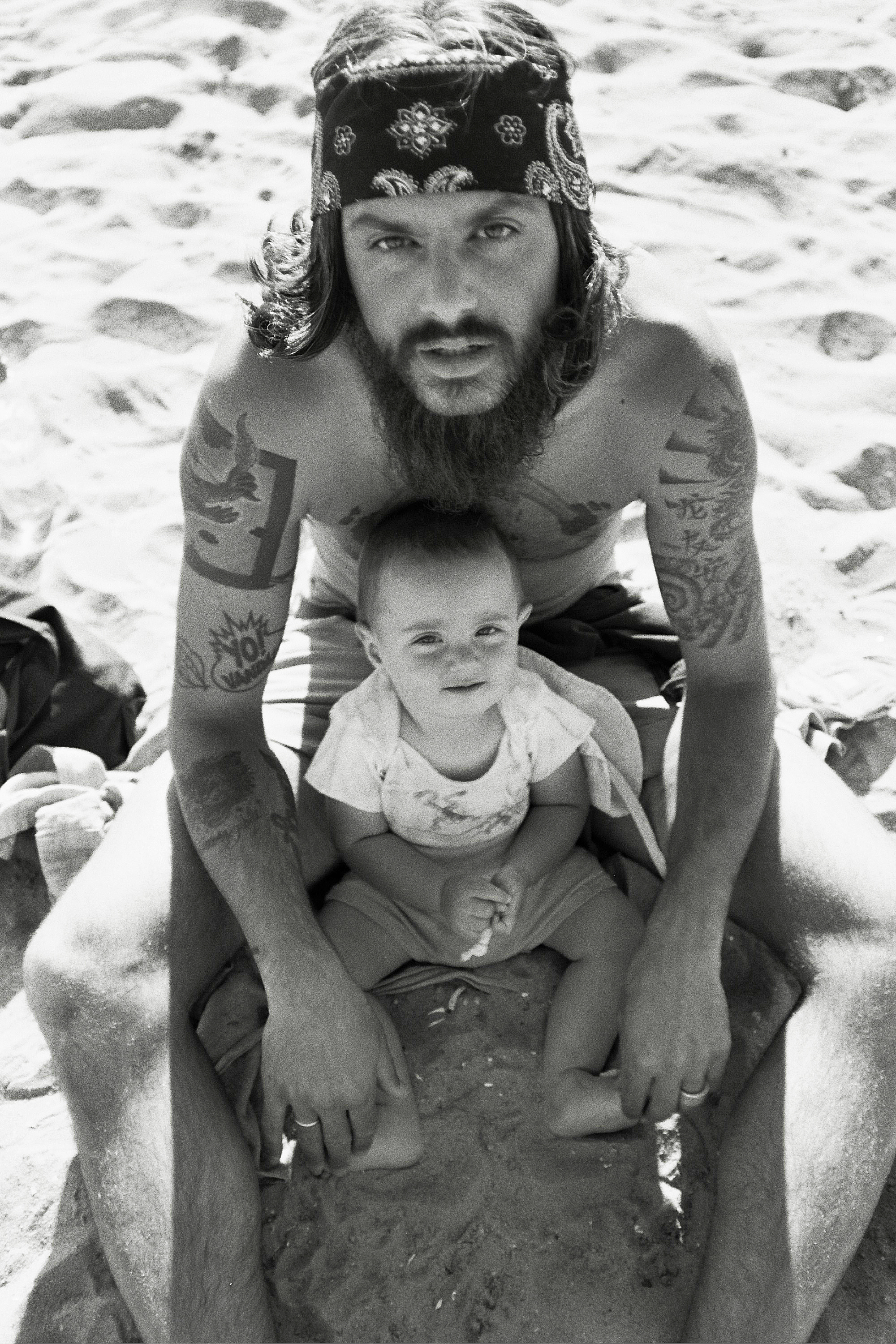

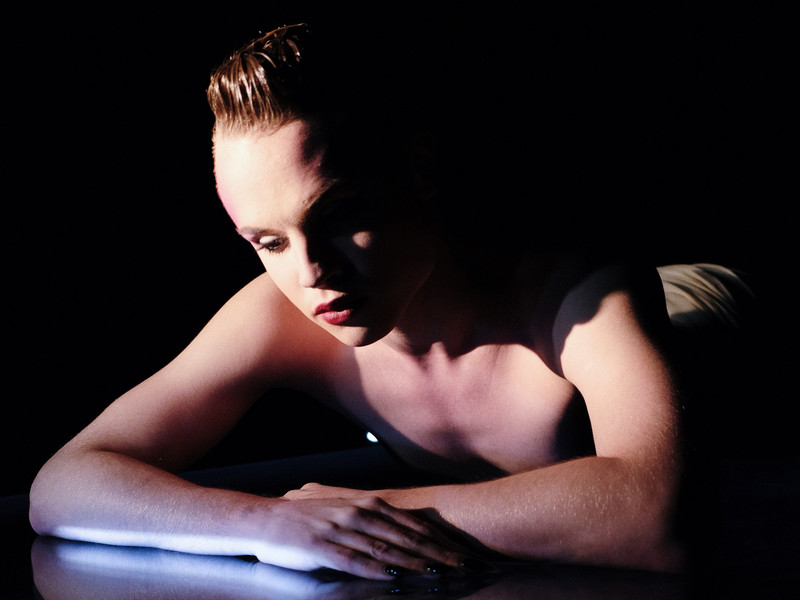

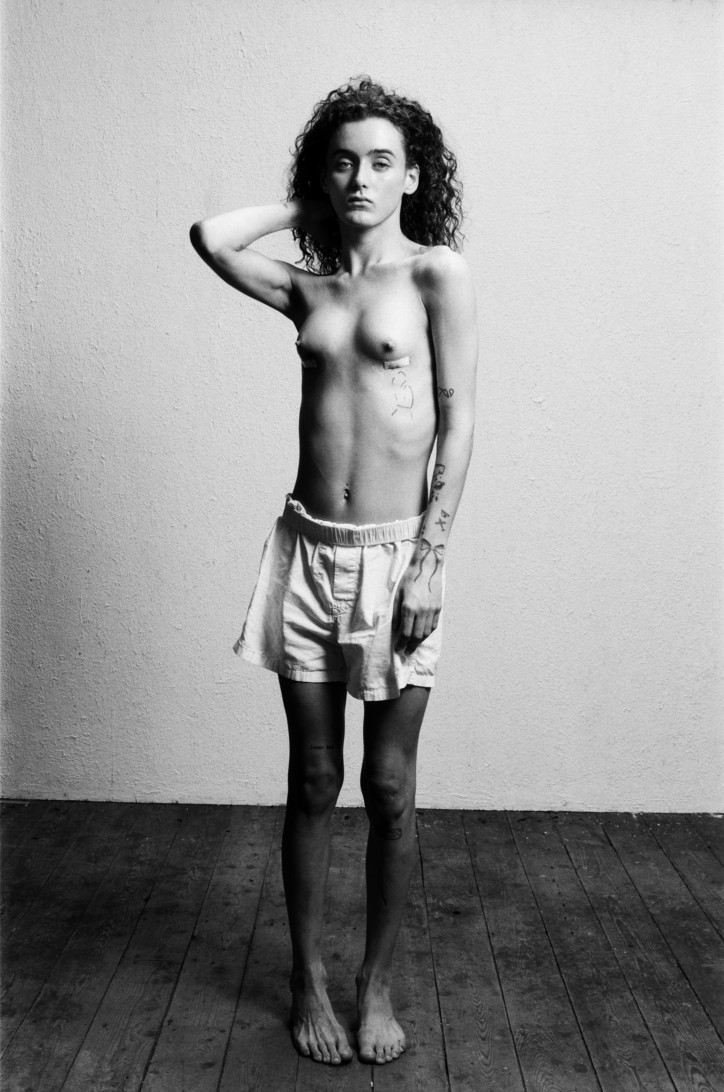

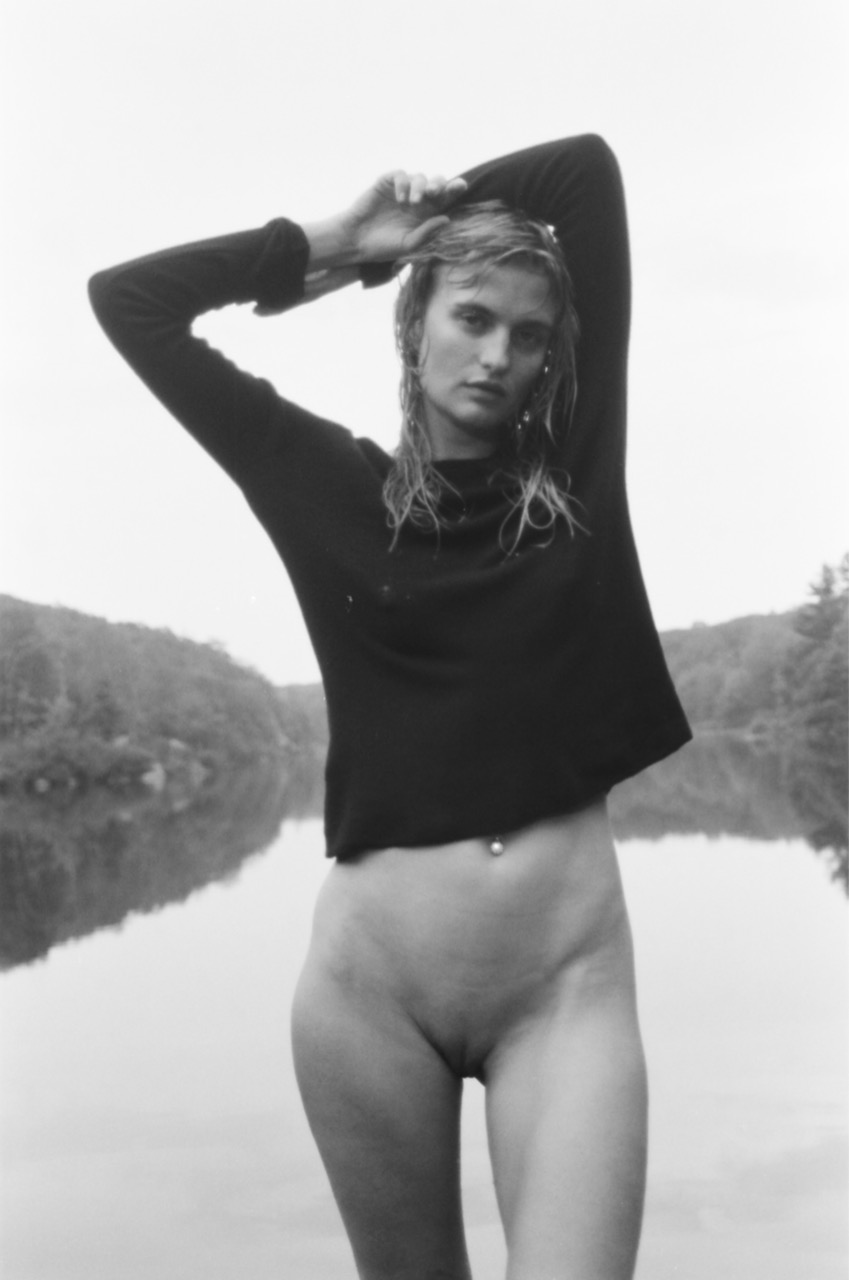

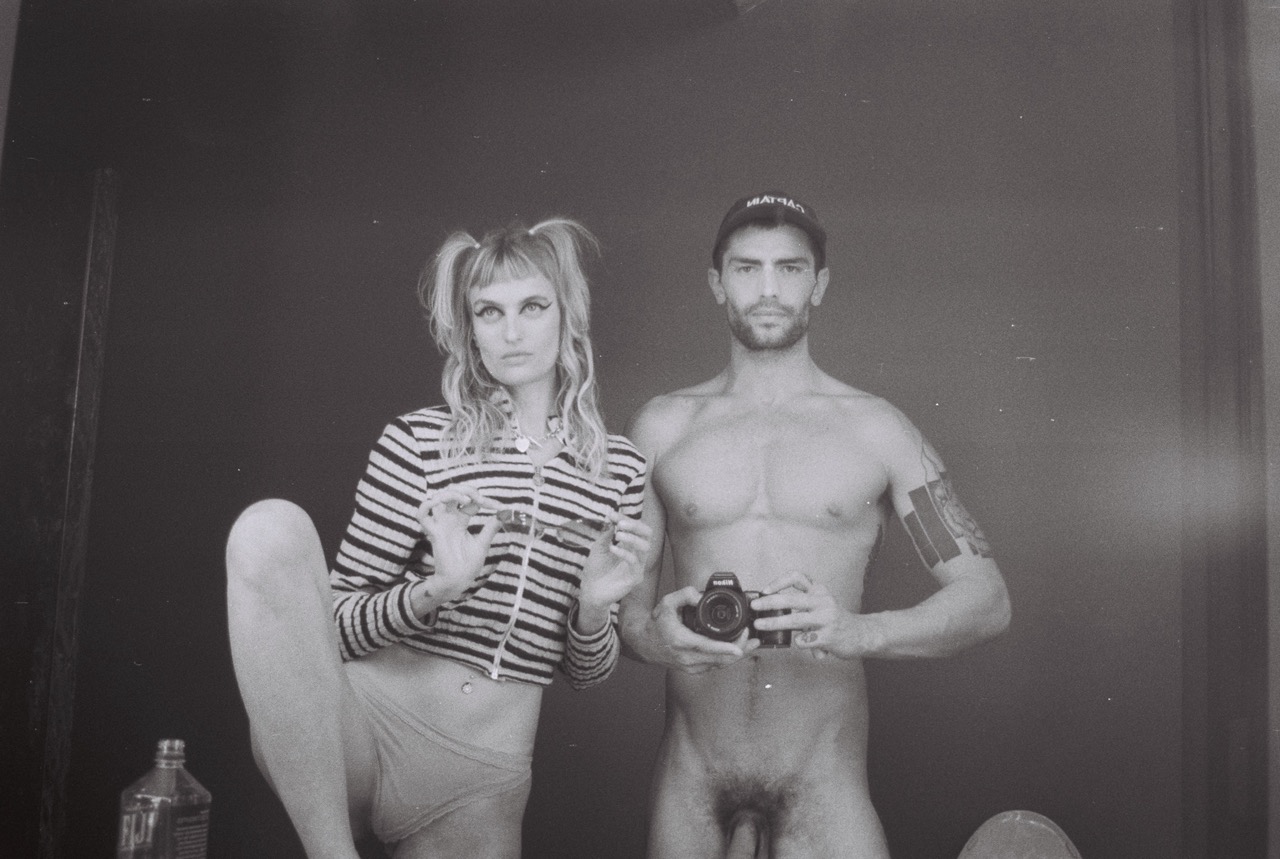

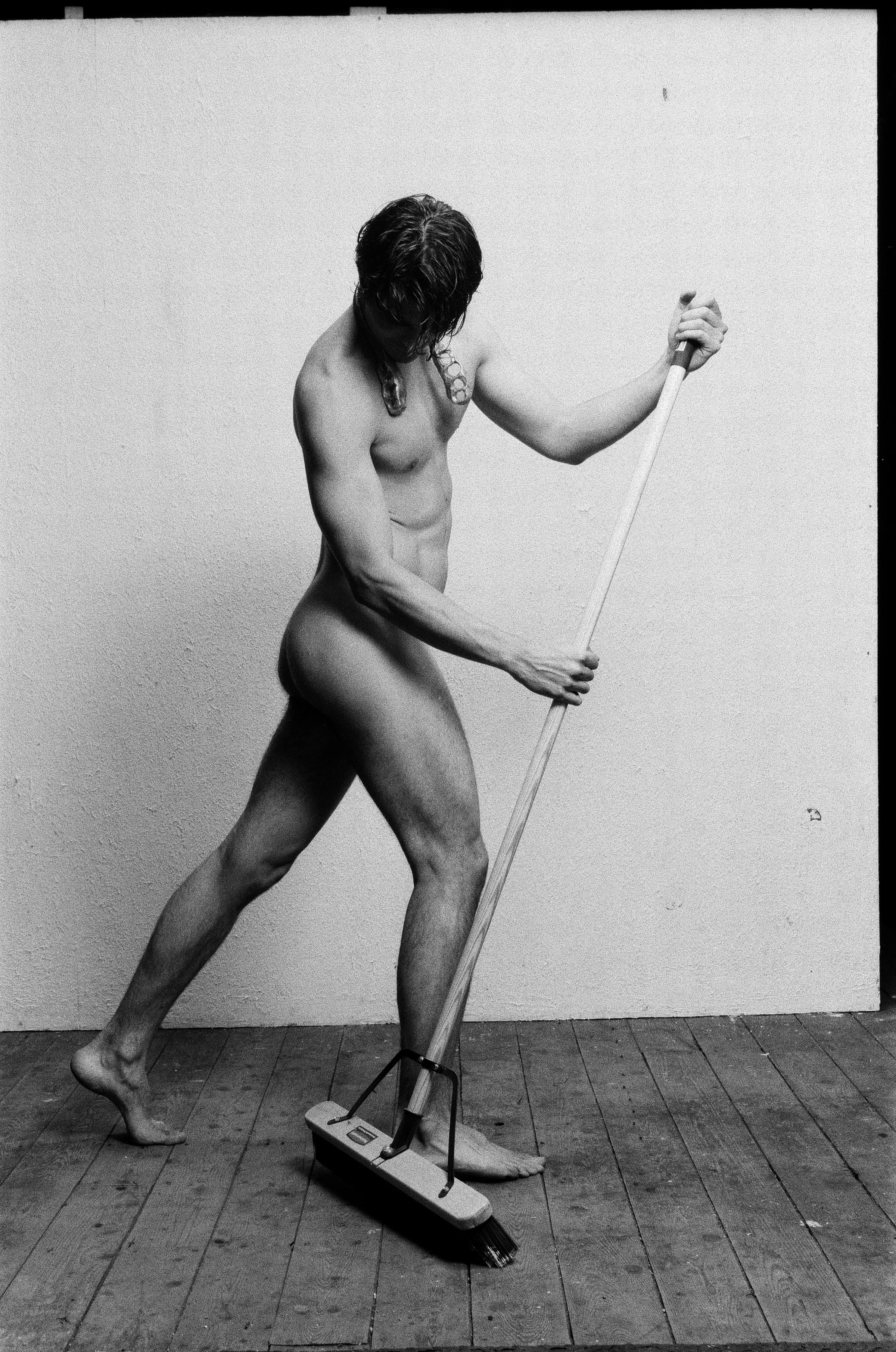

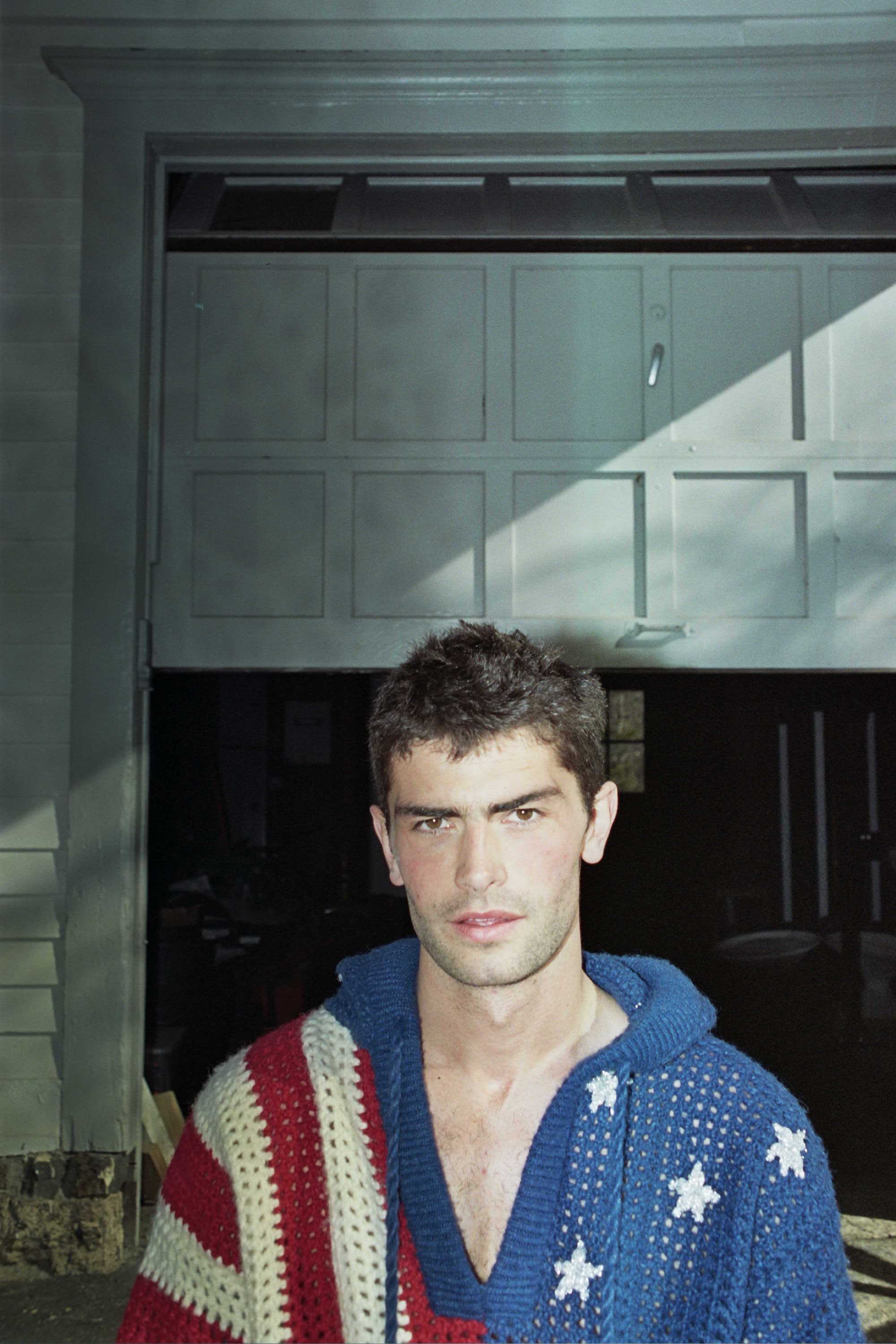

Above: 'Joel Osteen (Jessie Pierrot) part 2' and 'Joel Osteen (Jessie Pierrot) part 1' film stills.

Tell me about your work.

I’m a multimedia artist, but I primarily work with video and video installation, and Holy Fools is definitely the biggest project I’ve ever made, both in terms of the actual size and duration, but also in terms of how long it took me to plan this, to shoot it, to edit it, to get it to its final stage in the gallery. So, it’s the most work I’ve ever put into something. It’s also the first time I’ve ever worked with a real budget, which I think is very important for specifically video artists, because, at least in the way that I work, I have a lot more crossover with cinema or film than I do with video art, and you have to take a lot of those things into consideration in terms of production when trying to make something that functions within the film world. I had never had access to that before this project. So, I do kind of consider this the first project that I’ve made that’s really what I wanted to make, because I didn’t have those kinds of limitations to work around like I had with all the projects I had done prior.

Were you doing film before?

I’ve always considered myself an artist, but since I was 18—since I started in college—I’ve always worked with video, but I had never had access to certain types of collaborators or equipment that I had dreamt of having access to in order to make the scale of project that I wanted it to be. It’s not that having money, or having the right equipment, or the nicest camera, or the most elaborate lighting makes a project 'good,' but I do think it makes it very hard to express exactly what you want to express, as a video artist, when you don’t have access to all the tools that you want, unlike if you are a painter or sculptor—there are less variables that you have to consider.

I was just thinking that—a paintbrush and paint are no big deal, but all these things you’re talking about, like light, sound, actors…

Transportation for the actors, costume, makeup, property insurance, location—it adds up. But I felt that I could be as ambitious, or as creative as I wanted to be.

How did you manage to secure this windfall?

Banging my head against the wall for six months! I tried every avenue I could think of, and this isn’t really something you’re taught in art school: how to go about getting money besides going on to nyfa.org and applying for grants—most of those grants have a lot of specifications, location or age or the actual subject matter of the work, or they’re very small grants, which would be helpful for someone who works in another medium a lot more than it would help me. So, I ended up getting help from three different individuals—three patrons, essentially.

But I’ve diverted from the original question, which is to tell you about the project—the project is a reinterpretation of Bruce Nauman’s 1987 piece, ‘Clown Torture.' I had never seen the full piece when I got the idea for my own. It started as a little bit of a joke between a curator friend and I—we would share clips from YouTube of ‘Clown Torture,’ and we would also share tweets from a Twitter account called Clown Torture, which just tweeted lines from the never-ending riddle that a clown in ‘Clown Torture’ recites on loop, and in passing, as a joke, this friend said that I should make my own version. I jumped on it very quickly. This led to us going to the Art Institute in Chicago to the archives, which is where ‘Clown Torture’ is held—it wasn’t on view anywhere then like it is now at MoMA.

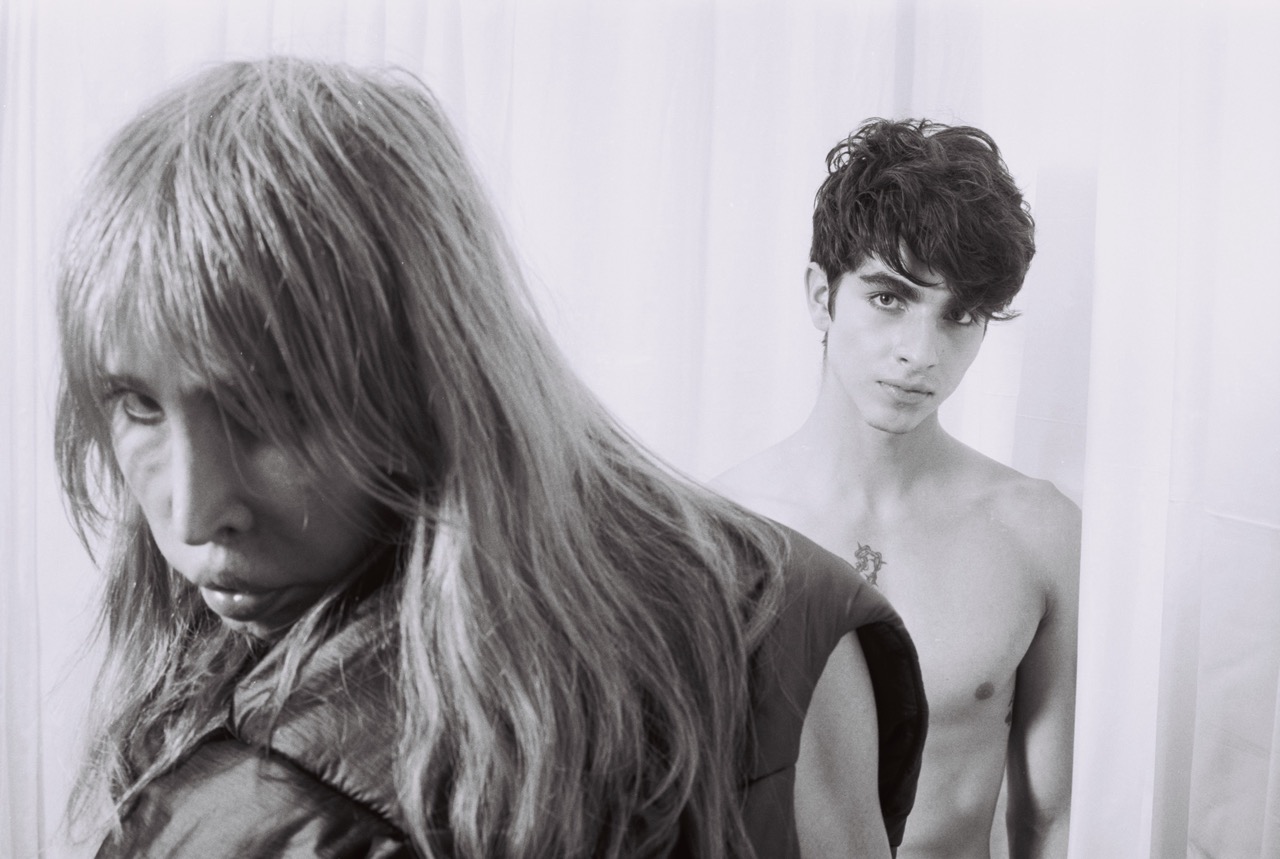

Above: 'Door (Jessie Pierrot)' and 'The Tyger (Rachel Auguste)' film stills.

So, it’s kind of a coincidence that MoMA is showing it now.

It is a coincidence, but my show being timed with the opening isn’t a coincidence—that was important to me, to have Holy Fools up at the same time as Disappearing Acts, the Nauman retrospective, because I wanted to, one, give viewers the opportunity to compare and contrast the works; two, I thought it would be potentially good press for my show; and three, I didn’t want to look too derivative or as though his retrospective had inspired my idea, which might have been how it seemed had I gone with a gallery or a show date which would have been long after the retrospective ended.

At the Art Institute of Chicago, I looked at all of the DVDs, all of the interactions that they had access to with Nauman and his makeup artists, the reviews that had come out the first time ‘Clown Torture’ premiered, original installation layouts, negatives—basically everything that’s out there that’s not on the internet was there.

Something really resonated with me about the idea of self-inflicted torture, which is the premise of ‘Clown Torture’—it felt, in a way, like an analogy to the art-making process—very masochistic and tedious. I also felt, at that time, in my practice, I’d been over-complicating a lot of projects I was working on—none of them were going in the right direction and I felt like this provided me with a simple formula I could follow, but contextualize to fit my own narrative. Even though ‘Clown Torture’ is abrasive and chaotic, when you look all the individual pieces, it’s actually pretty simple. It felt like a nice guidebook to use in order to make something different, something that references the original, but doesn't regurgitate what Nauman already did.

I chose to make the main focus of my project childhood trauma. Thinking about this idea of self-inflicted torture, I wanted to go a little bit deeper and make it personal for my performers—I wanted it to be, in a way, real torture that the viewer was watching and in a way participating in. So, I gave my performers a writing exercise where I asked them to share painful or traumatic childhood memories with me, and those writing entries served as my jumping-off point for scene building. So, the actions they do in their scenes are abstracted versions of the stories that they shared with me. Some of them quite literally reflect that and others seem potentially unrelated, but it was personal for the performers. There were multiple reasons I chose to do this, but one of the most significant reasons was to experiment with this as a form of exposure therapy: to see if, by having them repeat this in a real-time loop—so, unlike Nauman’s, it’s not a 30-second segment that’s played on loop, I have them perform a real-time repetition for up to 32 minutes—the idea is that it potentially releases some of the pain they have associated with this memory, with this story.

I liked the use of things from history—classicism, the William Blake poem—I was immediately in love with that. It was cool how you pulled from all these different sources. How did you end up landing on William Blake?

Well, I will preface this by saying that I made a promise to my performers that I would never share the sources for these scenes, but I do think I can divulge some things without referencing what they shared with me explicitly. With something like ‘The Tyger’ by William Blake, at least in a lot of prep schools, that poem is something that you’re forced to memorize and recite for the class, recite for your peers, the teacher, and then thinking about the meaning of the poem, the tiger and the sheep, the predator and the prey—I just think that relates to the whole basis of the project—the childhood trauma, a child being forced into a situation of prey, and whatever happened to them, whoever did it being the predator, whether that is a relative, or a friend, or a chance encounter that, for whatever reason, scarred them.

You said that you wanted to experiment with the idea of exposure therapy—do you feel like it worked? Did they react?

Well, it’s hard for me to really speak for the other three performers’ experience.

Oh—did you perform in it?

One of them, yes. Mine is the one with ‘The Magic Flute’ music, the lip-syncing and then the watching tv, which is a scene from Bergman’s The Magic Flute. But I think just the act of writing about something that you might have suppressed, or something that bothers you, provides you with a kind of release, and then knowing that whatever you’re performing is directly related to that, and then still choosing to participate, can also provide you with a certain amount of strength or power over something that happened to you when you were in a position of no power, when you were a child, when you had no autonomy, no independence and you’re just stuck in whatever situation you were in. I think there’s something about that that aids in a certain reclaiming of what was lost.

But that's also just one element of the project. The other element is about the viewer—it wasn’t just about what was happening on the screen, I was also interested in who is watching it, and I was thinking a lot about rubber-necking or Schadenfreude.

Remind me, Schadenfreude is when you enjoy someone else’s pain?

Yeah, Schadenfreude and rubber-necking are a little different—rubber-necking is when you know something terrible is happening but you’re unable to look away, like the phenomenon of seeing a car crash and wanting to watch.

Above: 'The Magice Flute (Ondine Pierrot)' and 'Woman (Rachel Auguste)' film stills.

I definitely experienced that with your show—I weirdly couldn’t tear myself away, and I had places to be.

I’m happy to hear that, because I’m kind of of the belief that everyone, to a certain extent, experiences this perverse, voyeuristic sensation, and that we all possess this gross curiosity, and are drawn to things that we know are bad, but wind up feeling guilty about wanting to watch. In regular life, you have people watching horror films, liking to watch the demise of celebrities, things like that.

Even just the news—the only things reported are bad things.

And then you almost want something even crazier to happen. I don’t think everybody is aware of this tendency in themselves—I think judgment can be passed very quickly on people who have a kind of fascination or interest or are intrigued by these things that are… inappropriate or impolite. So, I wanted to make the viewer aware of this in themselves, that they are a part of this project, that by watching this you are participating, that this performer is here for your entertainment, even though you know that whatever they’re doing is painful for them.

Well, it’s kind of the idea of the clown, in general.

A clown makes a fool of themselves so people can laugh.

Have you ever seen a really funny clown? Or have you only seen them in the context of horror?

I don’t think clowns are funny, but I haven’t always seen It either when I look at them—I’ve seen them as a child at birthday parties.

I went to an old school circus when I was a kid, and there was this really funny clown—and this was before I came across all the horror movies [about clowns]. So, I have a fondness for them in a way—when done well they can be pretty funny, especially when you’re a kid.

Of course, and I think that’s why I chose to have two different kinds of clowns—I don’t know if you remember the video, but there are two Auguste clowns, which look more like birthday party clowns, and their scenes were a little bit more lighthearted. There was Eileen Auguste, where she sang ‘Maybe,’ and she read the book upside down and scratched her ass and all those things, and then there’s Rachel Auguste who recites ‘The Tyger’ in a bunch of funny voices and gets dressed. Then there are two Pierrot clowns, which are more morose and melancholic—that was my clown and the scenes in the church, and the one with the door. I wanted to have a diversity of behavior in order to not really hit the viewer over the head with, 'Oh this is sad, this is bad,' and also to essentially represent the differences in how we all process and deal with trauma. Not everybody reacts in the expected melancholic way to bad things—some people make jokes. Think about comedians—they turn their trauma into comedy; they turn their pain into laughs.

'Holy Fools' will be on view through February 3.

Bruce Nauman's 'Disappearing Acts' is on view at MoMA through February 18, and at MoMA PS1 through February 25.

All images courtesy of Rubber Factory.