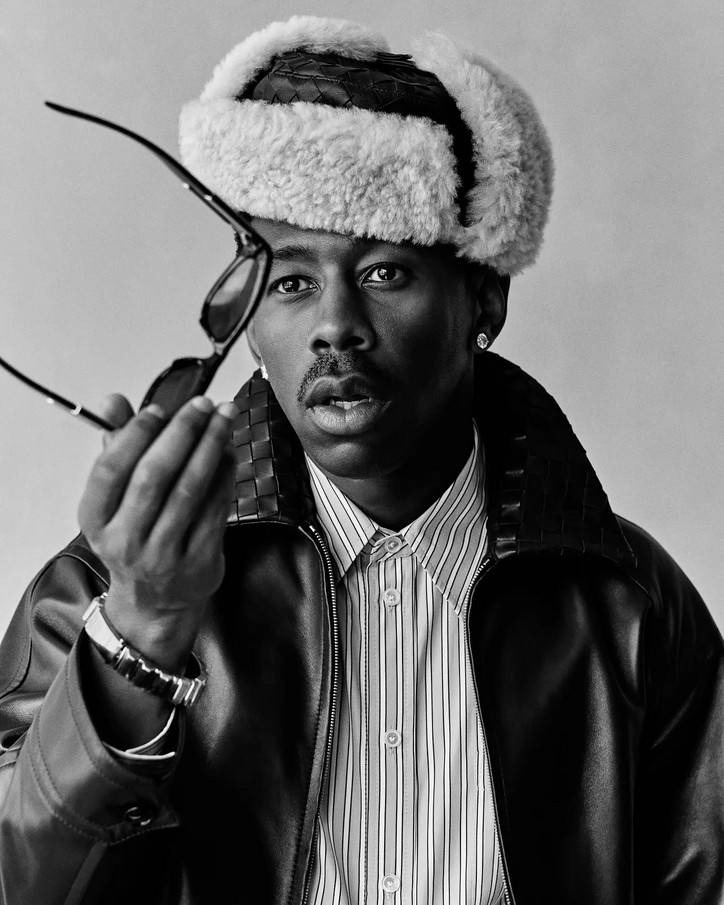

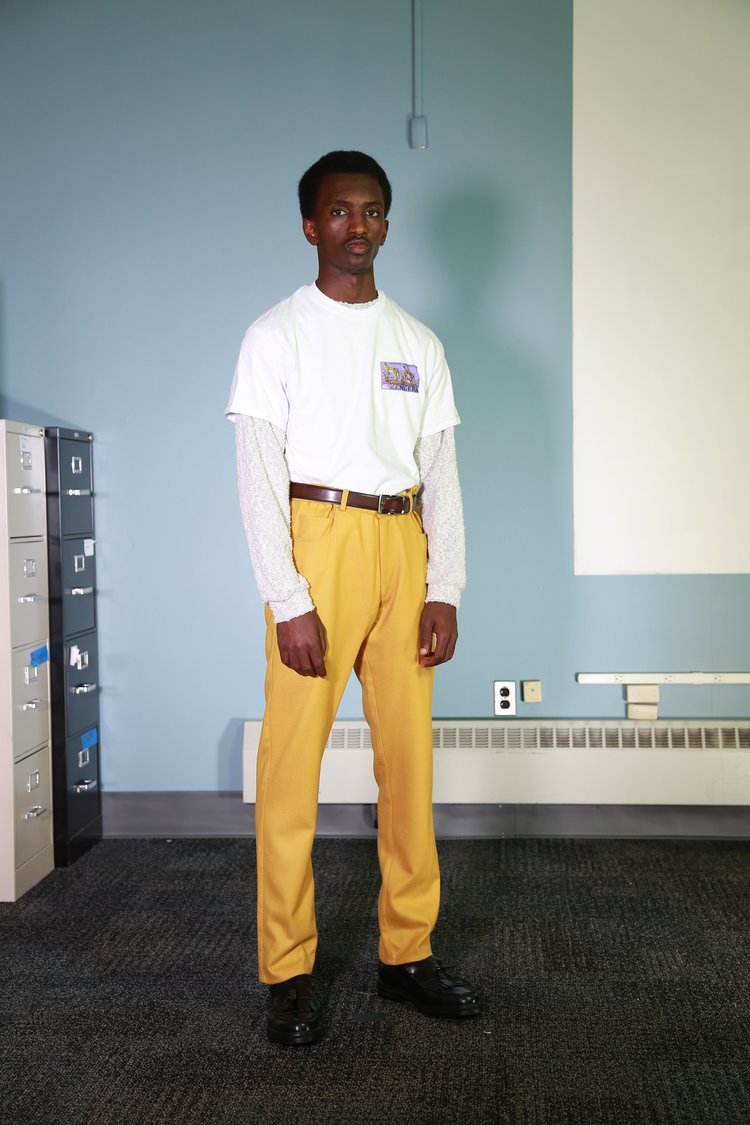

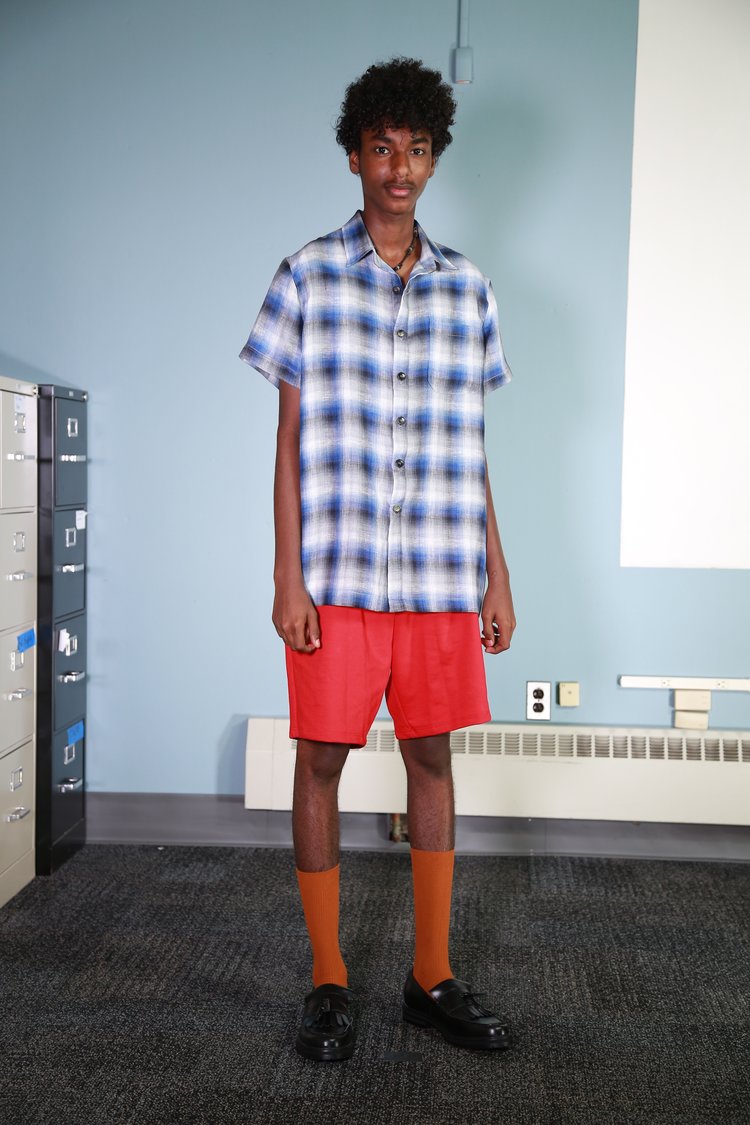

Head of State+

office met him at the Public Hotel to talk about his upcoming collection, his upbringing in Nigeria and what it’s like to be the fashion world’s kid brother.

He had just come from a whirlwind afternoon showing his sketches to makers in SoHo. He was working out the specifics of his upcoming collection: dimensions, pocket sizes, inseam width. “It’s the boring part, but the really important part,” he tells me. “These details determine how the clothes will hang, and can make the difference between a well made piece and a shoddy one.”

Abijako was hesitant to share details of his upcoming collection; since his shows are so in-depth and almost theatrical, he wants to save the major message for the audience. There were more than a few times that he almost spilled the beans before saying, “Wait, I wanna save that for the show!” Fashion Week spoilers aside, Taofeek had a lot to share with us about his feelings regarding what “mastery” means, on post-colonial politics and the social function of being a fashion designer.

So, tell me about your new collection.

I don’t wanna give it away!

It’s a secret?

It’s so secretive! But I’m debuting my next collection in February 2019 during Fashion Week and it's my second runway show. I personally think it’s my biggest yet and my best yet. I’ve been looking—oh my god—I’ve been looking so forward to it. And I just can’t give it away!

Okay, okay, can we talk about your previous runway show then? I feel like your shows are almost like performance art. Would you consider it that?

Yeah, in a way. It’s funny, I was recently talking to someone about the upcoming collection because we’re already discussing the casting and production, and I don’t want someone to come to my show and feel like, ‘Oh it’s just a fashion show.’ I want you to have the same feeling you have when you go to the theater and see either a documentary or a movie about a very important subject, and when you go back home you go on your laptop and look more into it. I try so hard not to do too much explaining during the show, and even though it’s all about telling the story, it’s still, in a way, subtle—it can’t be like an obvious story. I want the audience to do as much research as the designer.

So, you’re like, ‘This is your homework.’

Yeah, pretty much. You go to the show and I go, ‘This is your homework.’ Any outsider who hasn’t been through that kind of situation, especially a lot of Americans, their job is to go home, open up their laptop and research the impact the actions of our country are having on people from the other side of the world. And I hope that’s the feeling a lot of people have leaving, especially my next show, which I think is super important, not only to me, but also to my family, and the people that are represented in the show. Oh my god, I feel like I’m gonna give it away! I’m slowly giving it away!

Do you see there being a narrative that links each of your collections together?

Yeah. And that narrative is my narrative. It feels like I’m writing a book and that book is my life—the people I’ve surrounded myself with, the culture I grew up in, the social issues and political issues I witnessed back in Nigeria. So, in a way, the first runway show is the first chapter to an infinite page book. Each collection is a development of the previous collection.

I believe as designers, we’re not just designing clothes, we’re starting conversations. Either we start a conversation or we continue a conversation, so the reason why I consider it an infinite page book is, after I’m done with what I’m doing, there will be someone else continuing that story.

I’ve read some of your interviews and you talk about being in conversation with previous artists—specifically West African artists from the ‘60s and ‘70s. Would you consider that part of the book too, or something that you kind of build off of in a different way?

I never grew up in the ‘60s, I never grew up in the ‘70s, although speaking to people who lived in that time period, it’s very similar to what I experienced growing up in Nigeria. When I reference West African contemporary photographers from the ‘70s, like Malick Sidibe, Saydou Keita, and Oumar Ly, I relate to the characters in the picture. Looking at the characters and how they not only express their confidence, but the way they also translate Western culture, Western clothing and all of that, there’s a deeper political aspect to it. The West comes into Africa, colonizes Africa, and deprives most people of their culture. And speaking specifically about Nigeria, post-independence, there’s this huge scene of people taking Western culture and twisting it. In a way, it’s like reverse—like, ‘You come here and deprive us of our culture, well we take your culture and look, we can do it so much better.’

But at the same time, if you go to Nigeria, if you go to any part of Africa, the culture is still there. The traditions, the ethnic groups. The Nigerian music industry is a perfect representation of this. A lot of the artists are getting inspiration from hip-hop, getting inspiration from R&B, although they’re still making it their own—the originality is still there. And I think, if that applies in the music industry in Nigeria, and in the movie industry in Nigeria, it can apply anywhere, in any industry. Being an African and being part of the diaspora, I have to not only represent my own cultural background, but at the same time, stick to my original story of me moving to the Western world and my translation of the Western world.

So, you have this really deep message and really important political story to tell. How does that impact the way you view the rest of the fashion world? Obviously, not all designers are trying to create clothes with a radical message. Is that frustrating for you?

No. At the end of the day, it’s all about making clothes. We’re not firefighters, we’re not doctors—all we do is make clothes. Although we have the opportunity to tell any story we want, not all designers have to tell a story.

There are three [kinds of] people in the industry: people who just design clothes, and those people are just as revolutionary as the other two people. The other two people are people who start a story or a narrative, and the last person is someone who continues and furthers that narrative. I respect all of them, but the designers I relate to more, I don’t consider them fashion designers, I consider them storytellers. I consider them authors. And I say this with pride and with confidence: I don’t consider myself a fashion designer. I’m not a fashion designer. I have a story to tell, and fashion just happens to be another medium to express that.

If I want to tell that story, if I want to tell a story of that intensity, it has to be as pure—as raw and as honest as the person who’s been through that situation tells it. I don’t want it to come off as me explaining someone else’s life story, or me explaining what someone else has been through.

How do you get to that level of honesty?

It comes from researching as much as possible. Once you’ve consumed as much information as possible, you yourself become the information. Everything I put out there has to be subconscious and it has to be natural. It can’t be forceful—I can’t wake up in the morning and go, ‘I want to tell this story.’

Even the idea for my next show, it’s based off conversation, off research. A lot of the best art I’ve seen or come across—the artist doesn’t explain, although the story is there. The way you translate it would be very different than the way I translate it, although there’s one similar thing under it, and that’s the original story.

So, who are the designers that stoke your feelings?

Feeling is a personal thing. Just because I see a designer and I don’t feel, doesn’t mean that another person doesn’t feel that either. A handful of artists have made me feel or still make me feel. I consider those people the greatest of all time. And the majority of them actually are outside of fashion. With music, Fela Kuti is someone I grew up listening to my entire life and I still do. I listen to a Fela song and I look at myself in the mirror and go, ‘I haven’t contributed anything to this world.’ I haven’t achieved my full potential. If someone like Fela could tell his story as pure and as raw as possible, without any fear, what’s stopping me and everyone from doing that? So, Fela makes me feel, and I’ll continue to talk about him, and I’ll continue to pay tribute to him as long as possible.

I would say as a storyteller, you’ve done your job [if you get] one person to feel. That’s all you need. And that one person could be you, yourself, as the artist. The satisfaction of the creator is just as important as the satisfaction of the consumer. Everything in society is set up to appease and appeal and it’s all about consumer satisfaction—if you don’t satisfy the consumer you’ve failed. The creator’s satisfaction is just as important, and to me, I think it’s more important than the consumer. Fela isn’t about being commercial. Fela isn’t about mass appeal. He was anti-establishment. It would be a disservice to Fela to continue his reputation, but flip it and make it more commercial—it has to be as pure as possible.

Feeling it is when you look at it ,you get the exact same feeling as looking at yourself from an outside perspective. It’s a reflection of you. And I think that will be the end of my—the moment I feel, you know that quote, feeling one with nature? But instead of nature, feeling at one with my culture. Feeling at one with my upbringing. There was a significance to the way my parents talked to me, the things they made me do when I was a kid. I thought, ‘You guys are so annoying,’ but now I look back on it and I wish I could go back to Nigeria and do it all over again, looking at things a bit differently. My whole life, I think I will continue to pursue that experience again.

How do people respond to you when they see that you’re really young? Do you feel like you’re kind of a little kid in the industry?

Even if people see me as a little kid in the industry, I don’t mind it. Yes, people look at me as this kid, trying to find his way, but so is everyone else. We all have so much to learn. Even when I’m 40, I still want people to look at my work the same way they look at it when I’m 20. When I’m 60, I’m still that little kid. I want you to keep seeing potential for as long as possible. There’s no point of ‘I’ve learned it all.’ The world is billions of years old—that’s a lot of information from different generations. So, we all are still little kids.

There’s a Da Vinci quote—I don’t know if it’s real, but it pretty much said, ‘I’ve offended God and mankind for not fulfilling my best work, or my best potential, and leaving that behind.’ The way we look at Da Vinci, he’s someone who has mastered his craft. But the way he looks at himself is, ‘I haven’t fulfilled that.’ I don’t think anyone would ever get to the point where they have. If someone comes up to you and brags about how they’ve mastered something, they’re kidding themselves. You can’t master anything. You can’t master design. We’re all students, and life is the teacher. We need to get rid of the idea of someone who’s mastered their craft. Yes, experience is very important, but experience doesn’t mean you’re a master of something. Experience just means you’ve seen more and done more. What I’ve also noticed is the sense of maturity differs based on culture, and a 10-year-old Nigerian has seen a lot more and has as much maturity than a lot of 25-year-olds in America. And again, it’s all about what you’re exposed to. I grew up very poor, with 10 people [living] in one room. That one room was our kitchen, our living room, our bedroom—that one room is everything. Growing up in that, and also the political turmoil back home, the corruption, being exposed to all that—it forces you not only to mature faster, but also see the world in a different way. There’s one saying that a lot of Nigerians and Lagotians say: ‘If you can survive in Lagos, and if you can make it in Lagos, you can make it anywhere in the world.’

What have been the toughest lessons you’ve learned so far in fashion? Or the most unexpected?

The way a lot of people look at fashion from the outside, people think about the glamour, the runway, the models. But it’s much more than that. No one sees the struggle of the designer and no one sees the 10,000 hours that have been put in. But now it’s a whole other perspective, and that’s been a tough adjustment. Just figuring out, ‘Hey this shit is real life,’ and real life punches you in the face, and you have to get up 10 times stronger. And there’s still bigger obstacles down the road. It’s all about breaking down every wall that comes along the way.

Are there any frontiers that you want to move towards, new things that you want to try, new markets or industries, that you’re curious about?

Architecture. If I ever go back to school, it won’t be fashion, it will be architecture. Any time I see an architect I’m like, ‘Wow. You guys are really it.’ They live in the future more than anyone. It’s insane. I remember when I was in high school we went on a field trip to RPI and I visited the architecture side of things. Those guys are amazing. Imagine spending so much time being physically in the present, but your mind has to be consistently in the future. It’s just insane and I’m just fascinated by that—I want to walk in their shoes some day. That’s where design is very honest, because it serves a function.

Besides the upcoming show, what’s next for Head of State+?

I’m currently looking around for galleries in the city to do a months-long exhibition to further the narrative [of the next runway show]. I want everyone to see it. I want everyone to experience it. Clothing, art installations, paintings that I’ve been working on, video documentaries, and a documentary I’m working on with my friend. Pretty much, you know, the full visual experience.

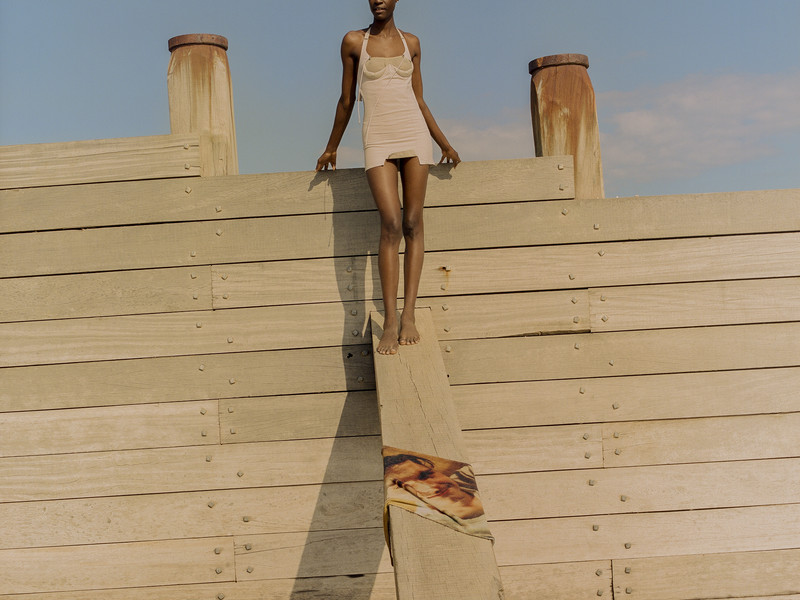

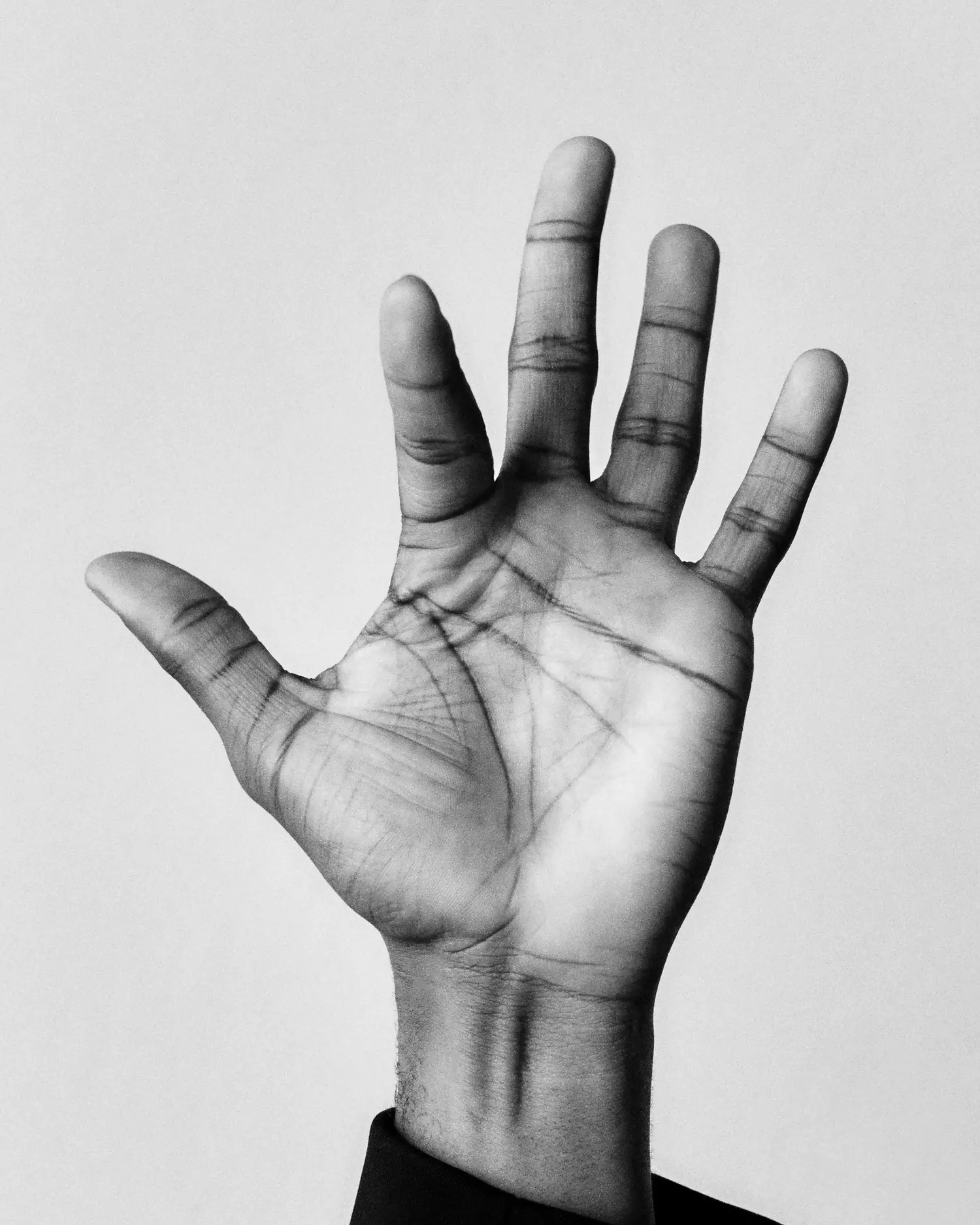

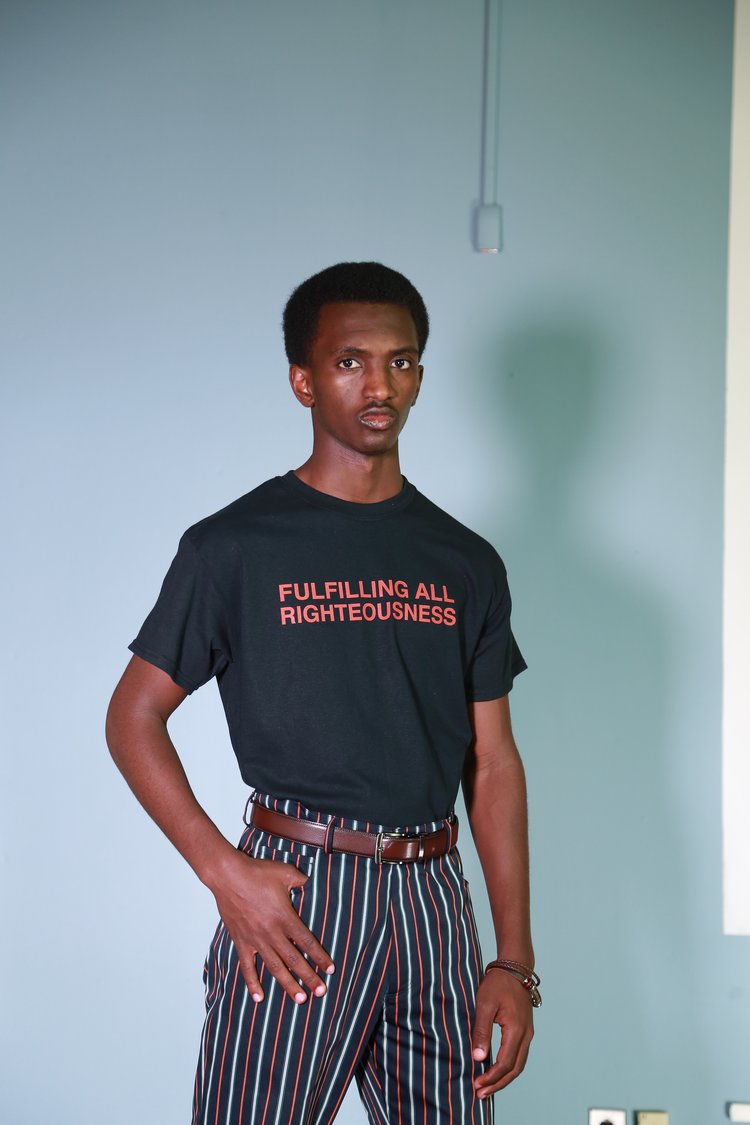

Photos from Head of State+'s 'Fulfilling All Righteousness' collection by Aden Suchak; courtesy of the brand.