SOL Abandons All Indoctrination

SOL’s resume similarly defies facile categorization; at 19, she co-founded a feminist media company called The Meteor under the direction of former Glamour and Self editor-in-chief Cindi Lieve, for which she served as Multimedia Editor; and as a strategist, she has overseen internal research and international marketing campaigns for companies like Spotify and PBS. She has directed, edited and been featured by publications such as Teen Vogue, Audible, TED, Harper’s Bazaar, and The Hollywood Reporter, and her lectures and writings often channel her personal experiences as a Black woman and a political organizer.

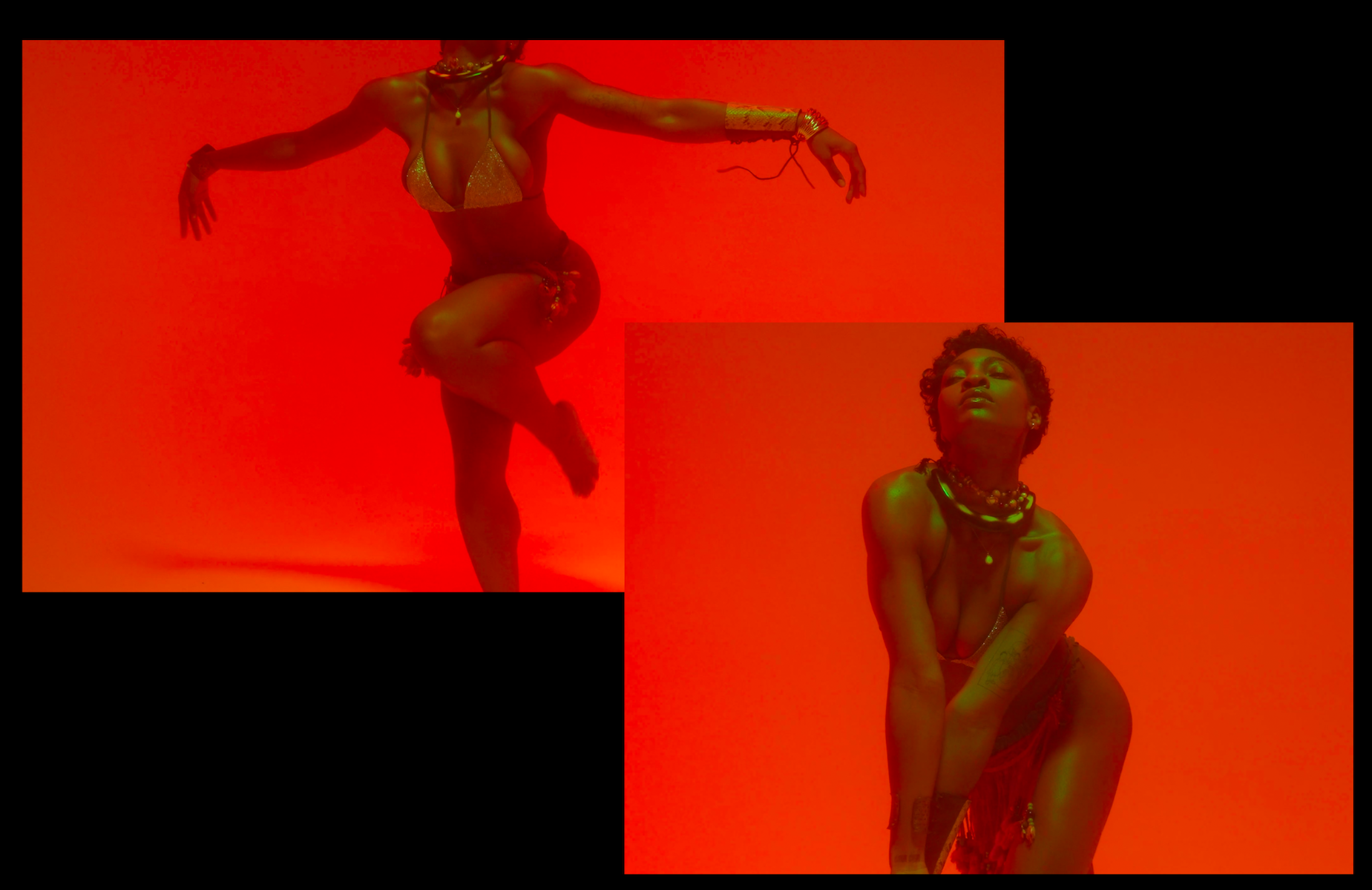

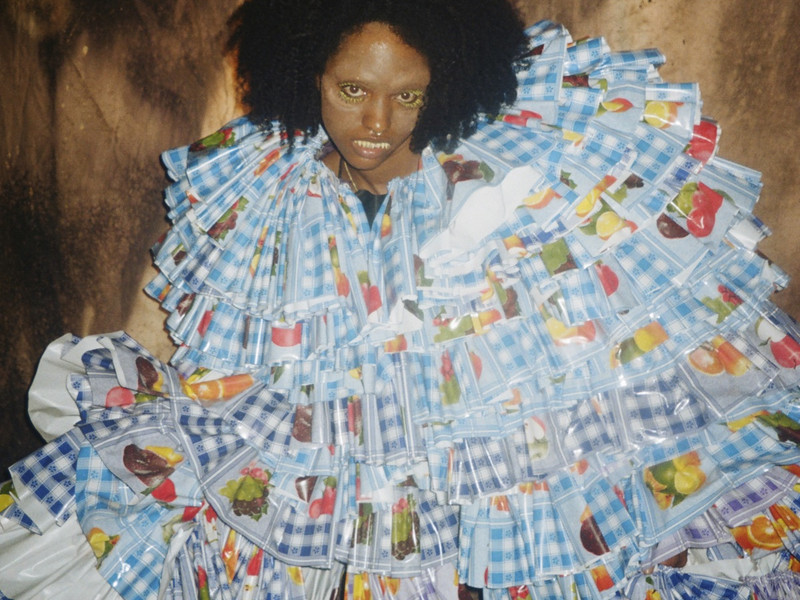

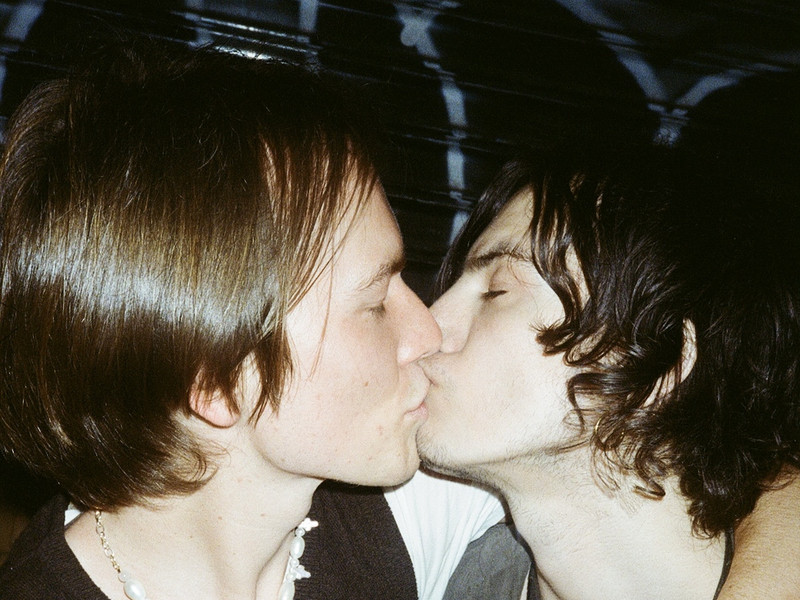

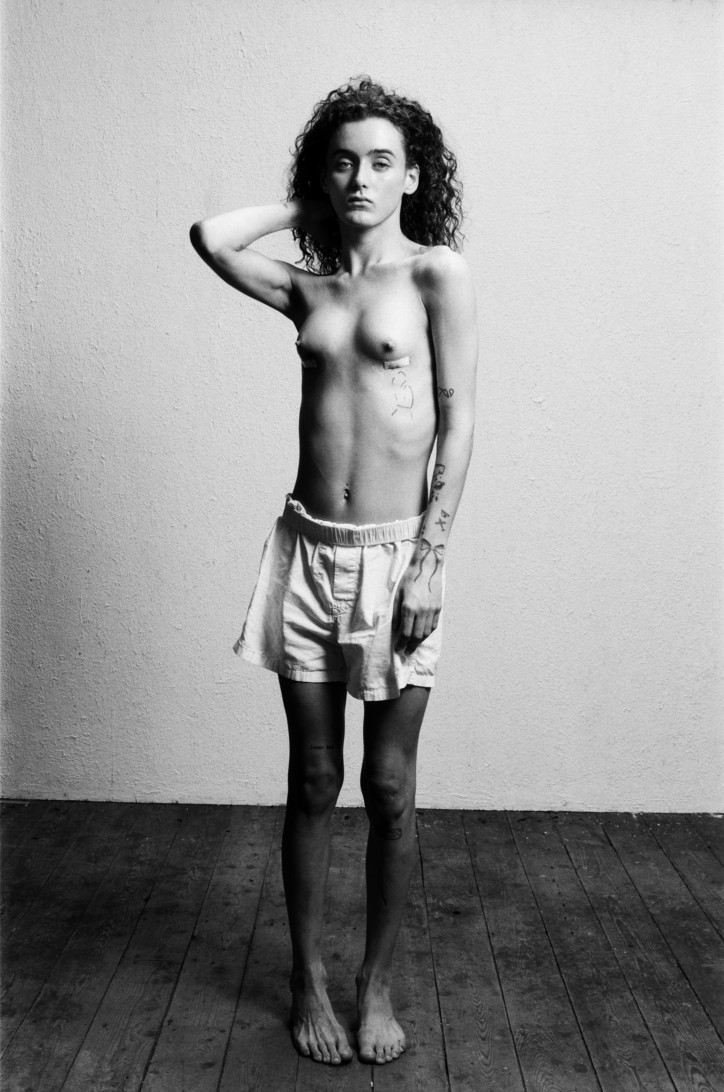

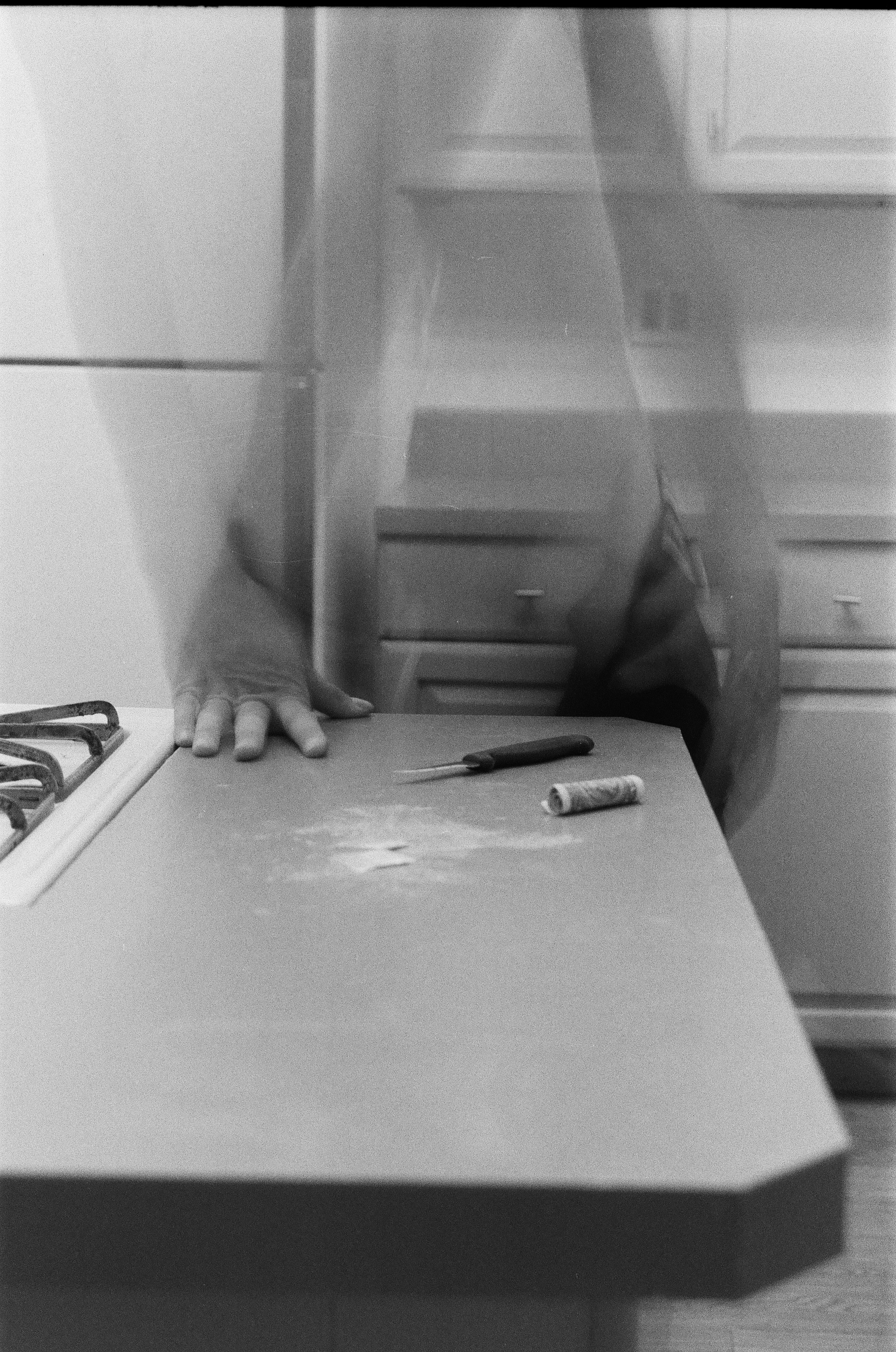

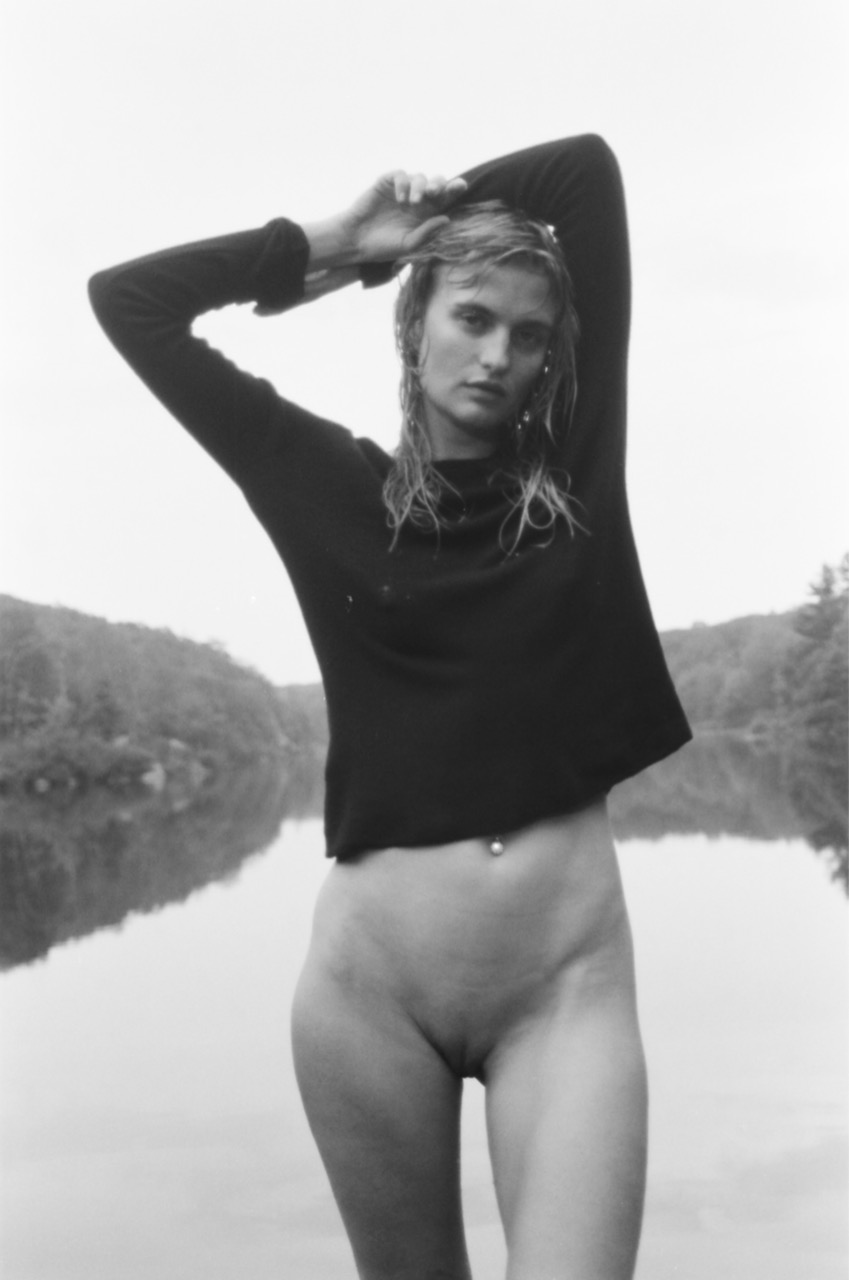

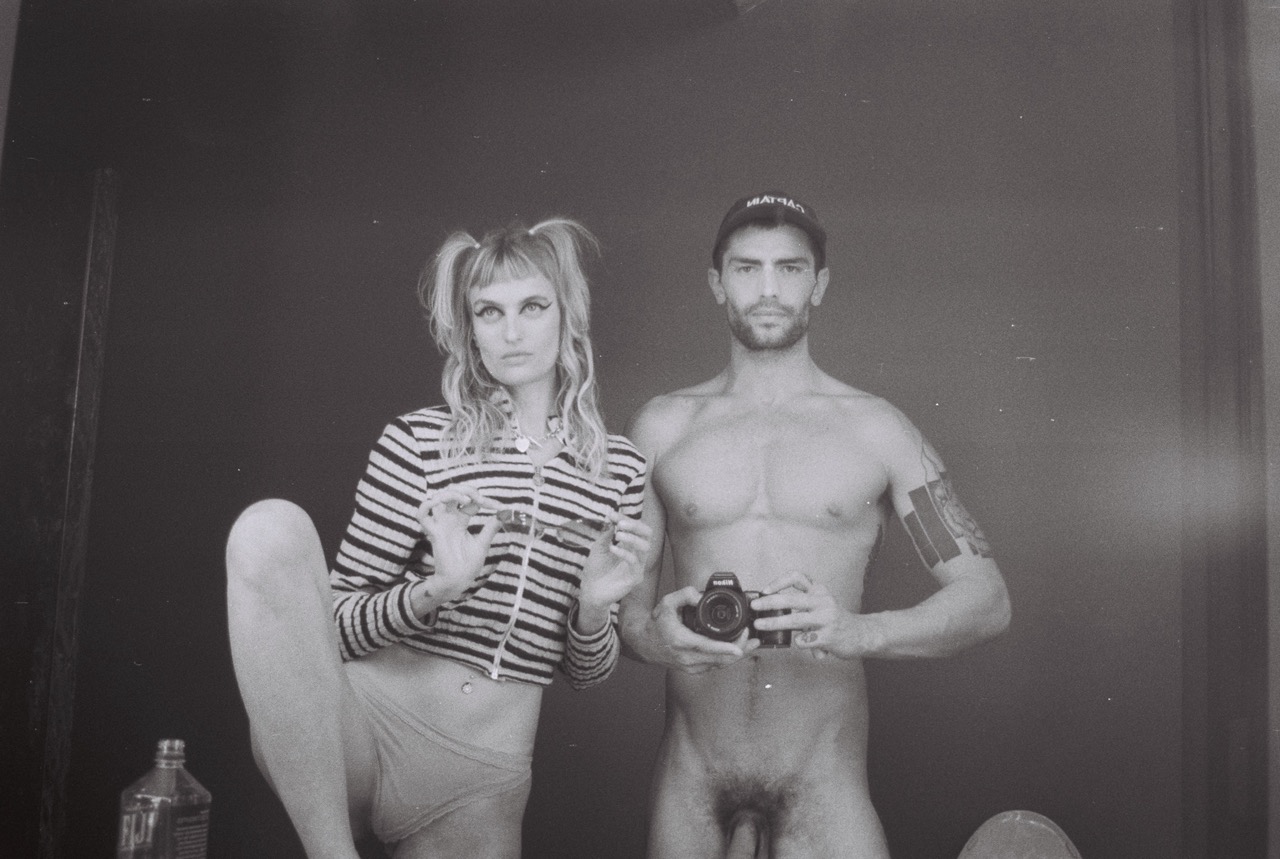

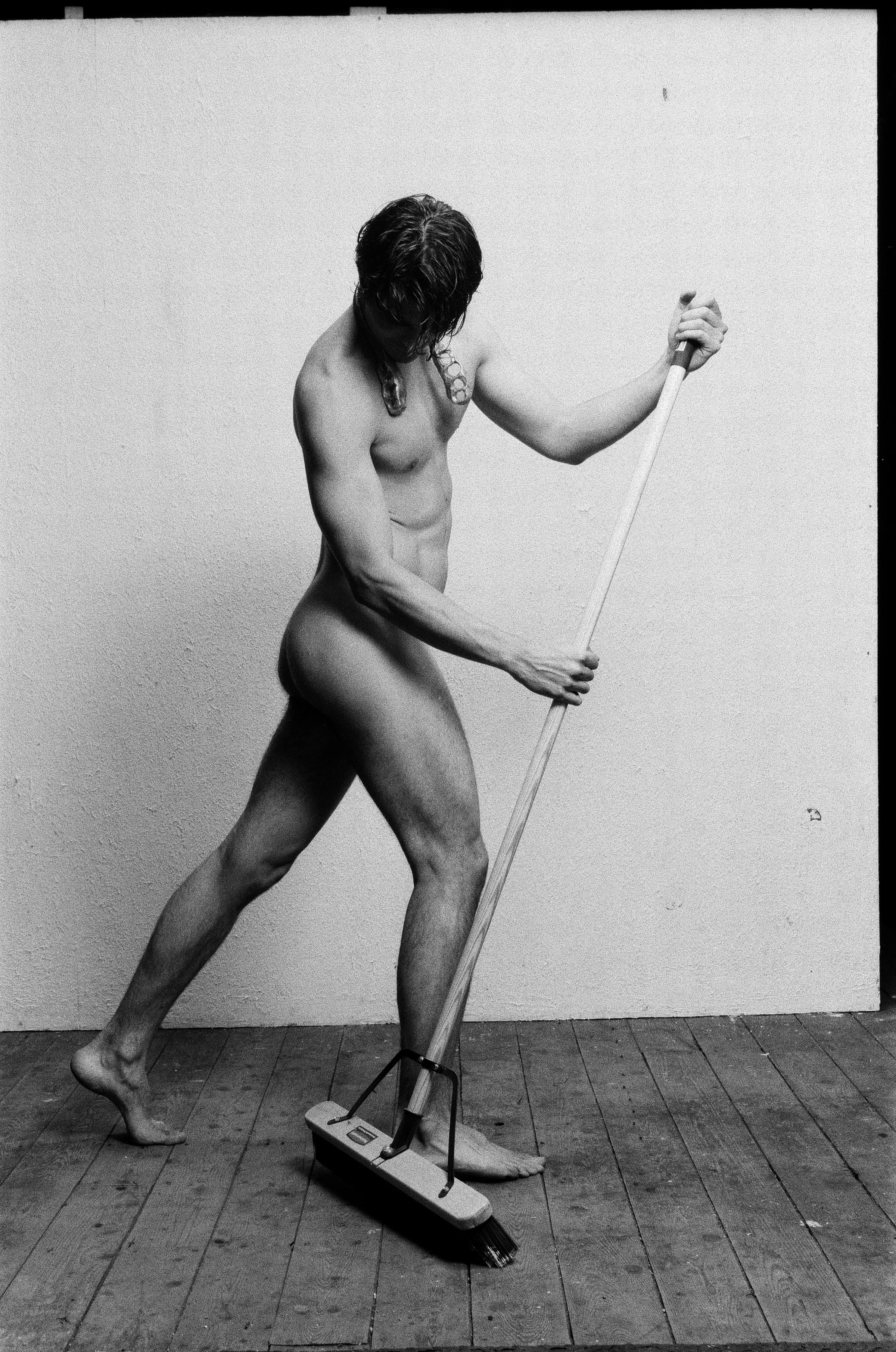

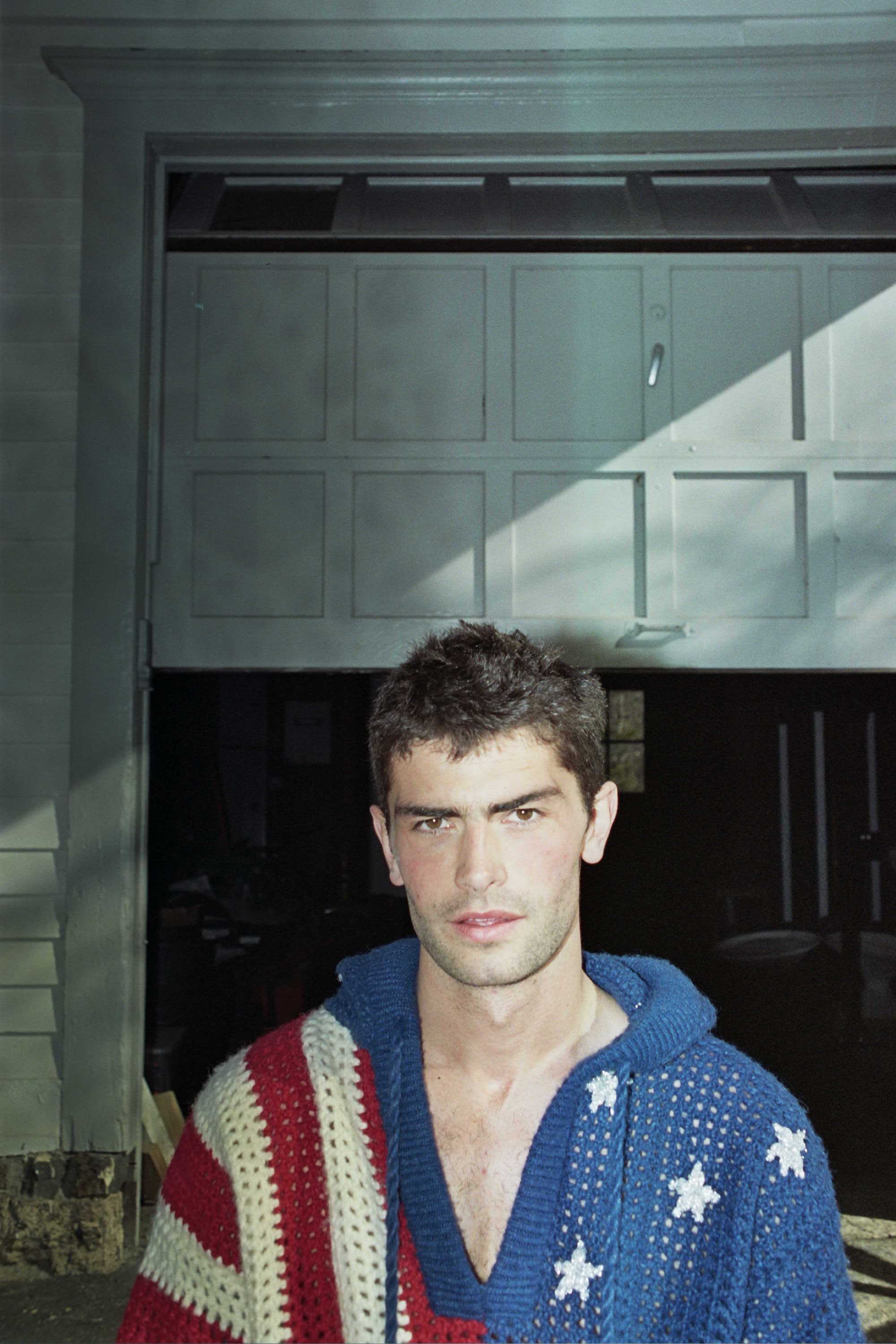

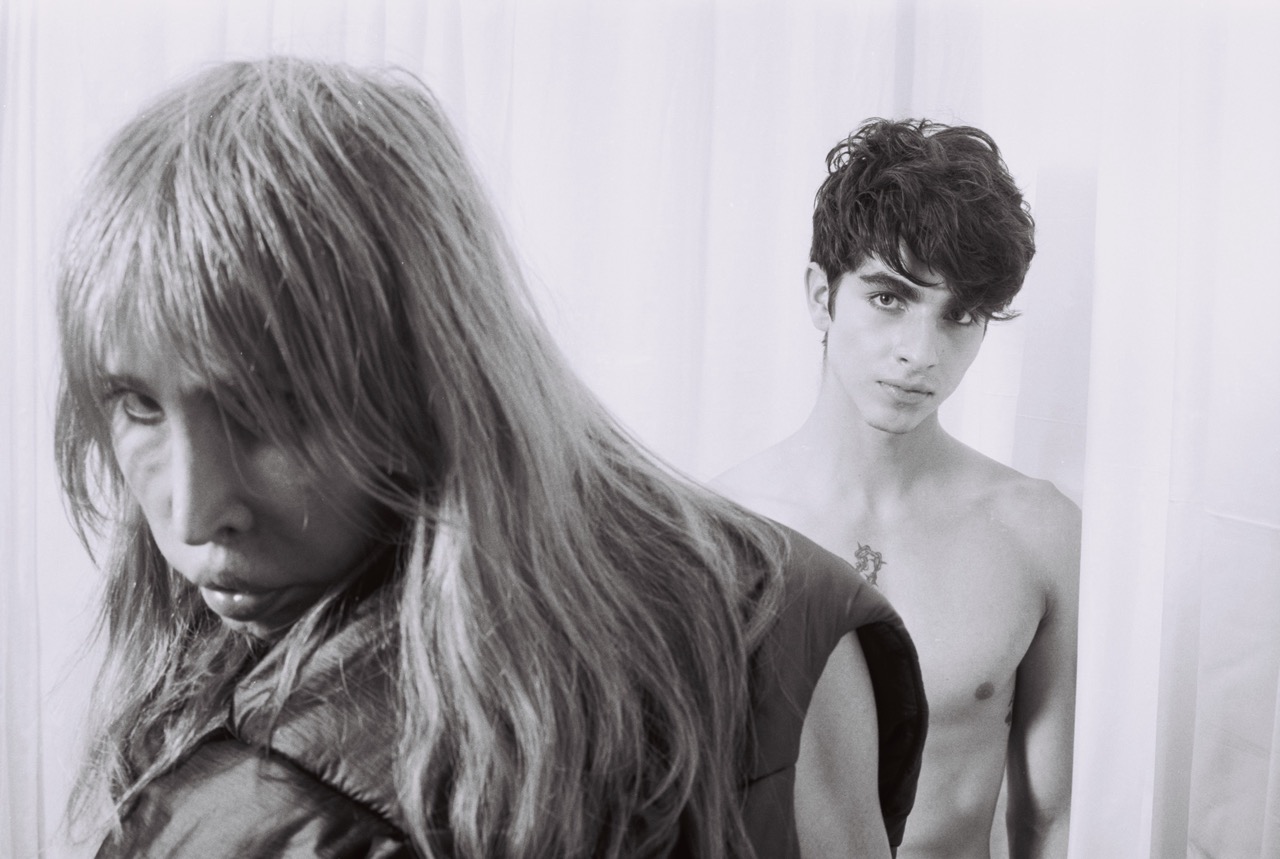

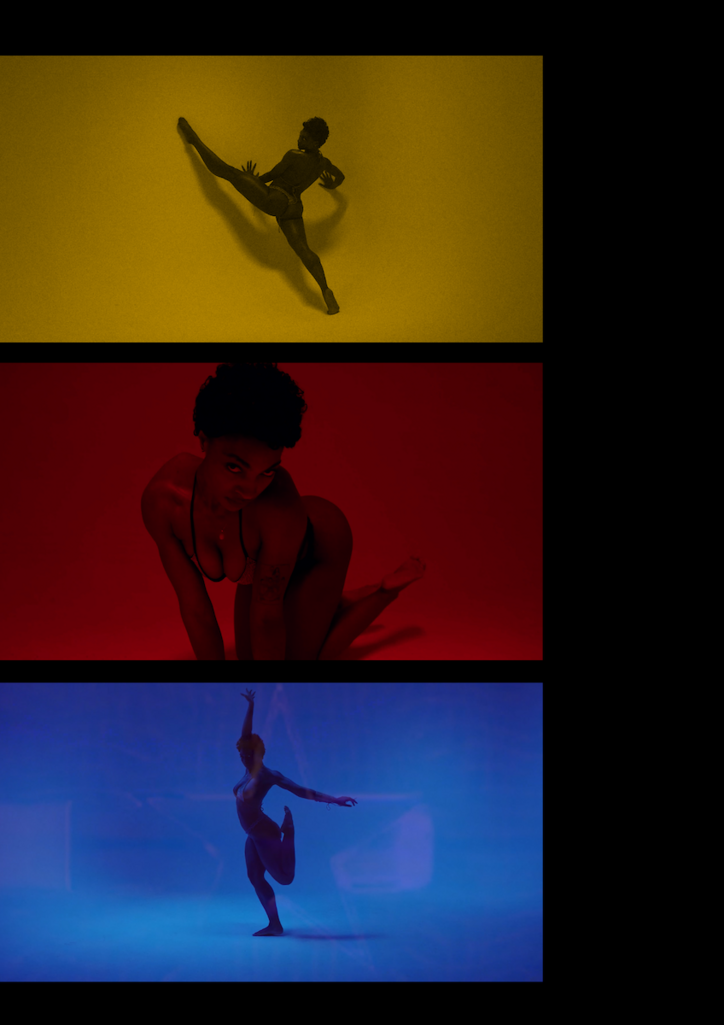

Her latest video project “DRUM GO,” shown in the stills accompanying this interview, is an entirely improvised homage to Black diasporic dance, set to an instrumental by Toro Y Moi. “DRUM GO” complicates mainstream portrayals of Black female sexuality as deviant and low-brow, “paying homage to black eroticism's cultural prominance dating back to ancient African cosmology” through the visual language of fast-cut viral social media clips and 20th century video vixens. “I’m stripping away the last form of branding from being so heavily institutionalized in my thinking and in my creativity, which is essentially the repression of sexuality” SOL says. “I've had my intelligence constantly undermined — there's a humility and a modesty that is imposed upon you as a woman. I’d become ashamed of my sex appeal as I pursued higher education and more prestigious, sophisticated spaces. This is a renunciation of that shame.”

SOL joined office over Zoom to discuss fun as evidence of freedom, abandoning the rules of her training, and why she calls herself a theorist. Read our conversation below.

In the last year or two, you took a step back from working in media to focus more on your art practice, both within your dance and your other mediums. What led you to making that decision? Now that your focus is there, how has the relationship evolved between your more tangible art practice and your other work, like speaking engagements and producing?

I am someone who is a student by nature. I really prefer to just get into the weeds and understand things on a technical and theoretical scale. So even though I had gone to performing art school my entire life, and then continued to train professionally and tour as a dancer by the time I was a senior in high school, I started to become interested in filmmaking when I transferred to Harvard from Middlebury. I abandoned the degree I was already pursuing. I started to study film because I wanted to know it in a more robust way, and I didn't want to have to self-teach in something that is super technical. I was always working within artistic mediums very closely because I was in school for them, but I was also working professionally to make money.

I hadn't honed my clarity of what I wanted to say to the world when I started working in media. There was sort of an intersection of my work with activism and my academic theoretical work, but I created this boundary between them in which I was working administratively within media rather than creatively. It was corporatized, so I just used it as a training ground. I got to a place where I'd established myself as a facilitator, established myself within media production, and my strategy work of finding ways to mobilize messaging was proving very effective, so I was getting work in that arena. Financially, the constraints aren't the same for me as they once were. And with that, I was like, ‘I’m ready to show what I actually care about.’

I'm ready to abandon all of the indoctrination of all of my training. There's a super major taboo that says you can only dance until your body gives out when you turn 30, and you can't do anything else if you want to dance. I was told all the time, “you can't go to college if you're going to be a dancer,” from the time I was six years old. It was like, “If you're really good, you're going to apprentice with a company, and then you're gonna get picked up and you're gonna tour and that's going to be your life.”

I just don’t agree with these concessions of having to bound myself in these ways. And so I tried to maintain my training and my facility, which is how it's referred to in dance, as well as possible throughout college. Once I graduated, I was ready to dance again, to dance professionally — and I didn’t give a fuck what anybody said, because my body is in the condition to do it. What I found even more miraculous is that my movement quality and style, which is particular to each dancer, had completely morphed in the absence of being in traditional training spaces. Because I was just out in the world, I don't know the influences that were enacting on my body, but they were changing the way that I moved. Despite having a very rigid classical background, I took to improvisational movement and blending genres and interweaving things and dancing to different scores than what you would traditionally see the movements I was doing paired with. This new nebulous practice just opened up for me. Once I felt more confident in it, I began to share it, and then I began to find work as a dancer.

Tell me about this upcoming lecture. What will you be speaking about? What have you spoken about in the past?

This upcoming week, I'm visiting a class that is focused on feminist joy. When I first attended Middlebury, I was studying gender, sexuality and feminist studies, along with history and international politics. I was preparing to create my own major there.This class was created as a response to the symposium last year that I was one of the lecturers for. I'm coming during their unit where they're studying eroticism; they're reading Audre Lorde’s Uses of the Erotic the week that I come, and then the keynote talk I'm doing is called “Deviant and Defiant Love: Paths to Self Fulfillment.” I’ll discuss the ways that rebels, freaks, and outcasts have been the catalyzers of major social and cultural transformations, and participants will reflect on nature as a diagram for cultivating self love and receive tools for overcoming insecurity in pursuit of their greatest potential.

Last year, one talk was called “Fun as Freedom: Alternative Proxies for Feminist Coalition Building,” and another was called “Blood Bound,” that was talking about my organizing work prior to going into media, which was in feminist menstruation activism and anti-poverty work.

For “Fun as Freedom,” though they wanted me initially to discuss my work in media, being the youngest co-founder of this media company with all these mavens, I actually decided to frame the talk around how I abandoned the convention of young professional ambition. The genesis of it was that I had gone through a period in my senior year at Harvard, where I was working full time — I was producing for TED, I took over the guest host role for Brittany Packnet Cunningham on her podcast that I was also a producer on because she was on maternity leave, I was on panels and doing a speaking circuit with one of my co-founders. I was working more than I'd ever worked while I was finishing my senior year. I was also going through a really, really, really hard breakup. I was going crazy. It felt like a really pivotal moment in my life, but I couldn’t really express it because there was an expectation of professionalism that I didn’t want to breach and topple my success thus far.

But something told me I needed to go in the exact opposite direction of my fear. And so I dyed my hair blonde, and I changed my Instagram name to “prettybadass.” I started to throw parties and started to literally introduce people to psychedelics in a really organized manner. I created a punk collective called “Sookie Sookie.” I was so afraid of destroying this one persona of myself that I realized it was critical that I do exactly that, otherwise I would be imprisoned. And so I did the speaking circuit with my bleached blonde hair. I was doing break dancing at this point. There was a lot going on. [Laughs]

But it made me recognize that fun is such an organic sensation. You're either having fun or you're not, and you know it when you feel it. I recognized that in a sense, fun is actually a really good indicator of if you're free, because you can't engender the feeling of fun while you're stressed or anxious or sad or afraid. Even if it's just the intermediary sensation in between these other anxieties, fun is not a comorbidity of stress and sadness. It is the absence of it.

I was doing prison abolitionist work, from the time I worked as a clerk in the public defender's office in Baltimore on their felony division, to my time organizing with Black and Pink, to my independent work. At one point we were doing noise rallies outside of Brooklyn [Metropolitan Detention Center], banging on pots and pans to let the people inside know that we were there for them. That was all it was, and it was fun. During the queer liberation parade during COVID, which wasn't supposed to happen but did anyway, I was photographed by the New York Times dancing — literally me twerking in the street. I've come to realize that this through-line of how I organized and how I went about building coalitions was not based on just collective suffering, but rather wanting to model what liberation looks like even within the confines of these oppressive matrixes.

For this upcoming talk, they came to me and said, ‘this is the unit, what do you think about it?’ And I think that my ministry has really just become rebellion and self sovereignty. Not looking to do these things en masse, but starting with an emancipatory view of yourself. What do you really want? Who are you really, what is your nature? That's why nature is the diagram for autonomy —things in nature operate just as they are, they're not being governed by anything other than how they operate, and everything seems to function.

For many years, you did your work relatively behind the scenes, and now you’re very consciously emerging into the spotlight. What caused that shift for you?

There is a very minimal digital footprint of so much of what I've done largely because I remained off of social media for much of my young adulthood. I needed a certain degree of privacy to change and become and experiment without having to be beholden to what I was saying or thinking or feeling.

It's interesting to be reaching a place in my career in which I am so present in the spaces I've aspired to be in, but there's this next leg of what I want to do. I want to reach people and I want to connect with people. I don't feel like I'm in a cocoon of self development anymore, in which I need to be hidden or feel that I don't want to be on the record. I've cultivated my perspective and my voice clearly enough that I'm OK with even the faults and the errors being documented. I want for my gifts and my talents to be recognized, as well as to be able to honor the people who've poured into me and helped establish my career up until this point for me to have the liberties to create the ways that I do with the people that I do. I'm not gonna retreat again until it is that I've attained the shit that I want.

I think you might be the youngest person I've ever heard call themselves a theorist. What does the self-label mean to you, and how do you find that framework helpful?

I wrestle with it because it's not sexy. [Laughs] I'm always sort of teetering a line of over-intellectualization and accessibility, and I don't mean this in terms of language because I am constantly telling people that the foremost critical thinkers in Black theoretical, sociological, and anthropological space were formerly enslaved people. I repeat that notion of accessibility not to mean the thoughts are too lofty, but rather that the label has been so co-opted and made insular to academia, when the most profound theorists I've met came from the hood, every single time. The most profound ideas come from my uncles, they come from my childhood friends, they come from people that are not traditionally educated. That’s why this is a label that I do take pride in, though I understand how it can be alienating. There are people who still understand that their experiences are the raw material of collective understanding. We're at a stage of modernity, where there's so much in recirculation, it feels like everything has been said, every perspective has been seen. I think a lot of people concede to the place of repetition and emulation — we see it in fashion and media, not just with trend cycles, but literally people replicating exact photo shoots. That is a form of becoming motorized, and I resist that.

I think I have perspectives to contribute to the canon. We've never lived at this time. Everything is unprecedented in that way. I'm seeking to make meaning or discover meaning, and to extricate myself from the shame that I may say something wrong — or I may say something new, which is also quite terrifying. In the beginning of Alice Walker's book In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens, she actually quotes Van Gogh, who said that he was struggling from a scarcity of models. I feel that for myself, as well. I want to canonize my thoughts and my experiences for people who are like me. I feel like there is something revelatory to our individual experiences, and I'm authoring mine.