I See Myself in You

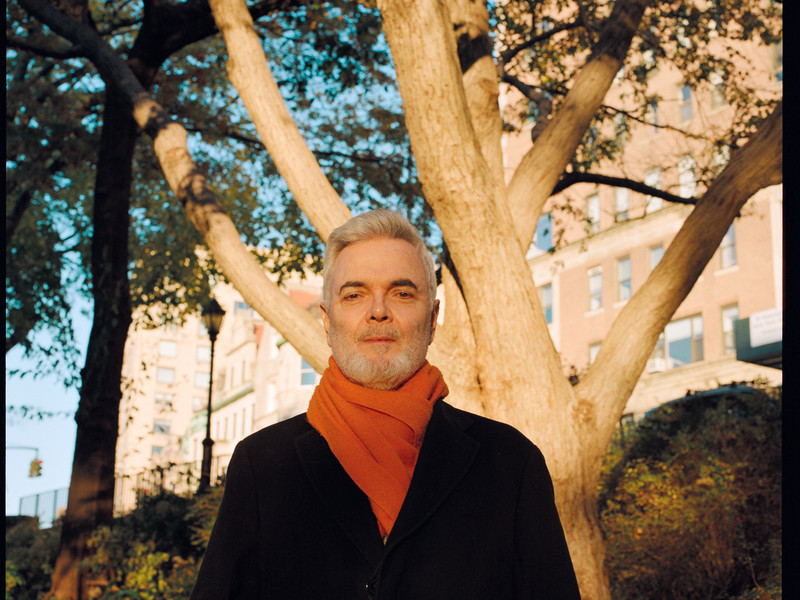

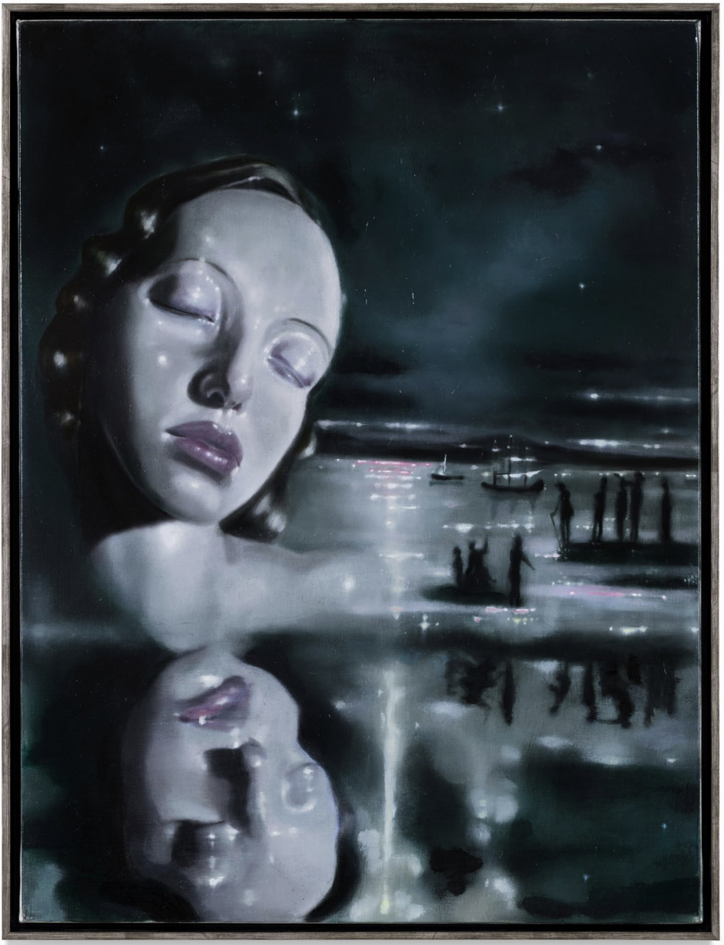

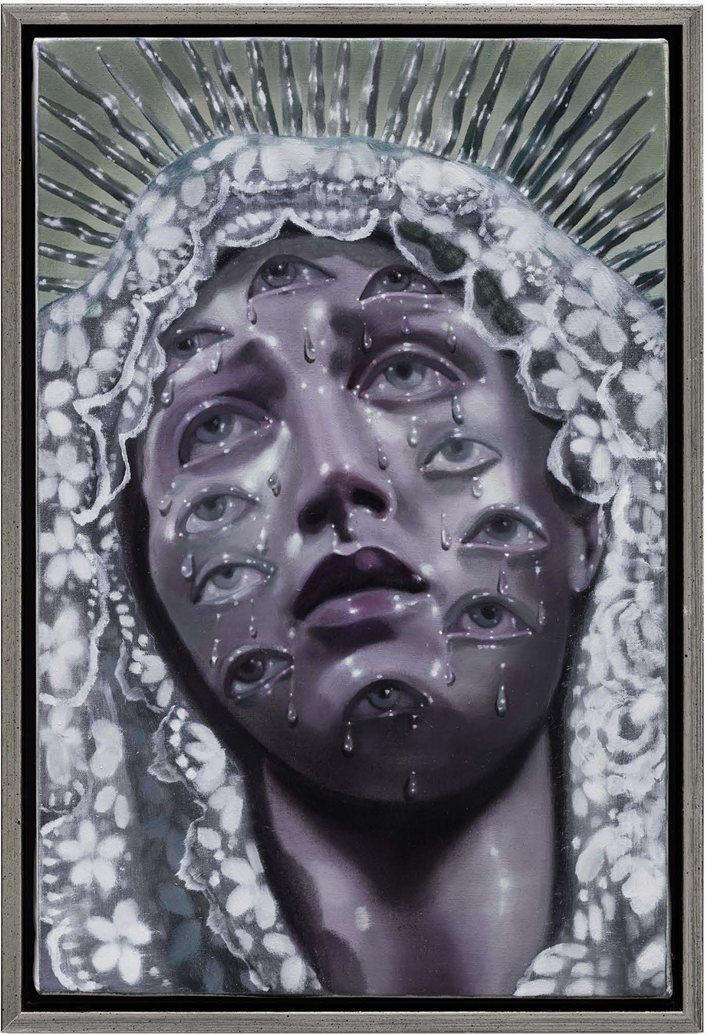

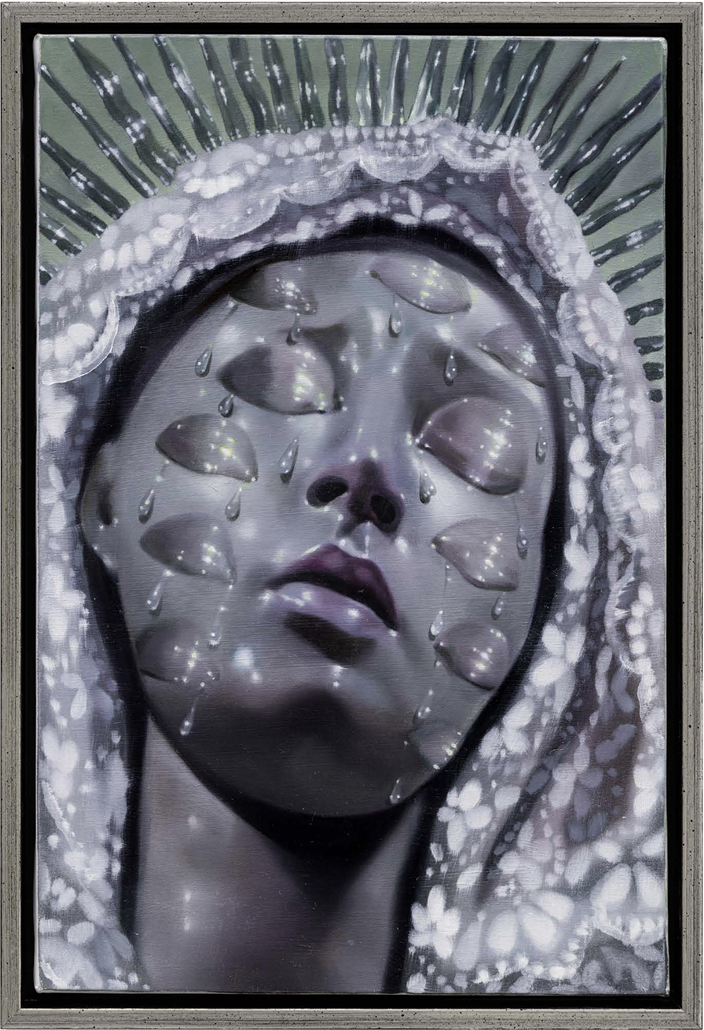

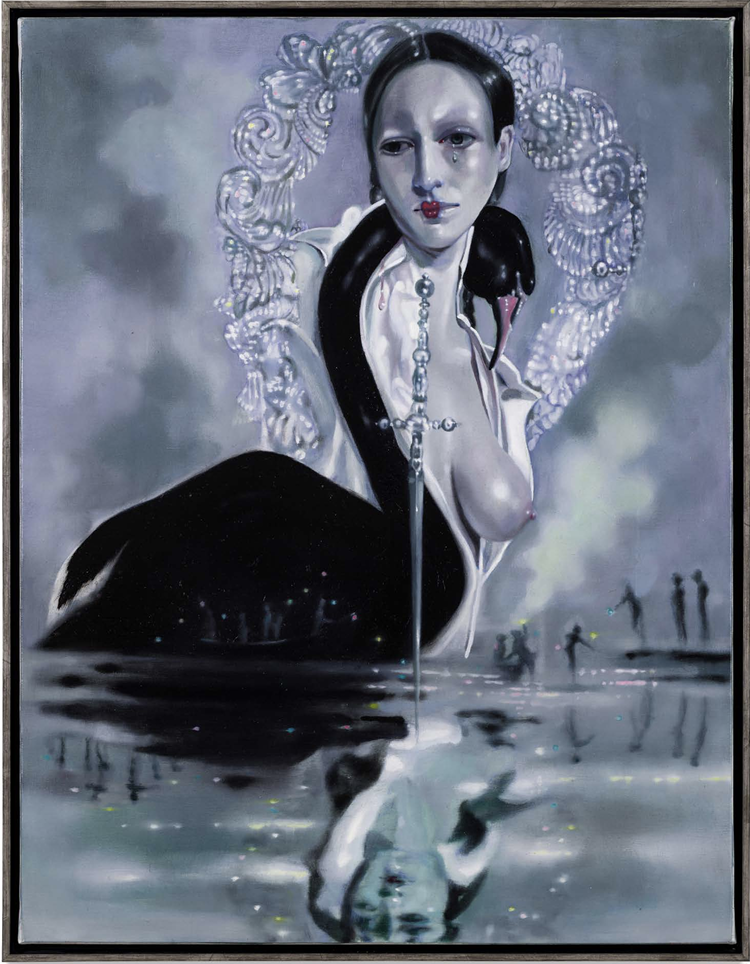

office stopped by Cruz’s studio to talk about inspiration, their identity, and how all of this manifests into an explosion of color on their canvasses. Cruz’s current exhibition Days Later, Down River is now showing at Monique Meloche Gallery.

As your work is heavily rooted in your Filipino identity, what are some aspects of your heritage or upbringing that you aim to share with your audiences — perhaps intricacies that the general public does not know about your culture?

I try not to think about what people will think of the work, but some of the things that I find exciting when I'm making the work — and I hope that comes through in the work — are some of the more spiritual things that I'm learning about these days. I think now that I know the history, which took me a little while to learn, I'm starting to learn deeper concepts. I have a mentor who's like my auntie. She lives in Queens and teaches me about Filipino spirituality. She's the best. There's this idea I always reference that means 'I see myself in you' or 'I see myself in the other,' so we really have this shared connection. Sometimes going through the archives feels really intense. So I think having that kind of protection is special. There were all these stories when I was growing up about magical amulets and how they would protect you. I just love those kind of stories.

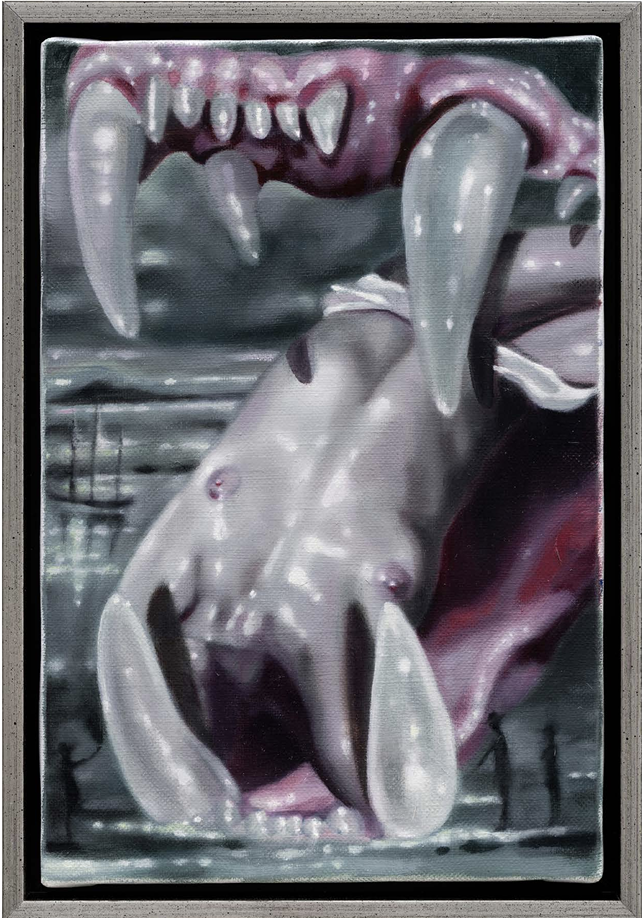

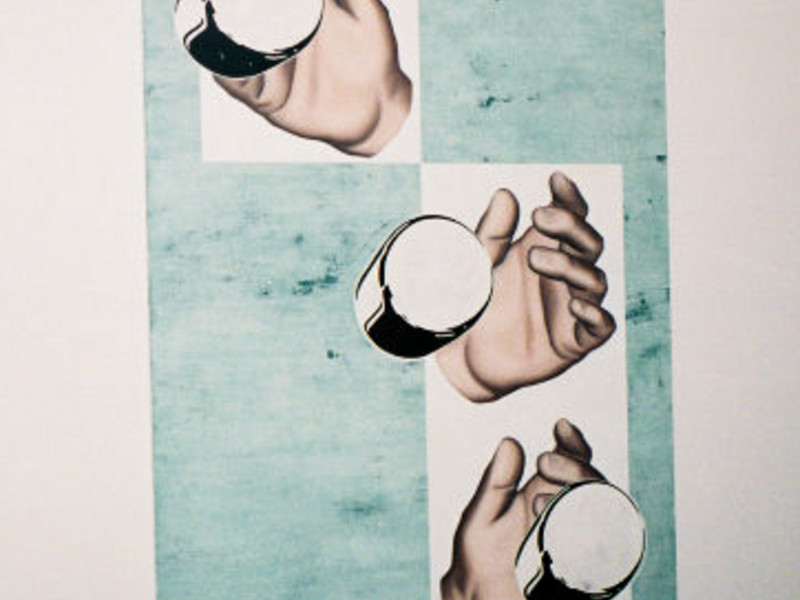

I have an altar in my studio as well. This is a talisman that my auntie gave me called a "kamay" plant, and kamay means hand. I think there's something deeper than what we have been taught — at least for me, about my culture. A lot of those stories have been somewhat buried or attempted to be erased. So for me, that's what I feel like these paintings uncover in the process of looking at these images and in the process of talking to other people who have experiences from these locations. In the artistic process and the painting process, I don't quite know where it's going to go, but when it goes from a photograph to a painting or to a sculpture, something changes. Something becomes revealed and I don't know if I can verbalize what that is, but I think it's special.

I think there's something really interesting that you touched on. You discuss how these ideologies and spiritualist thinking are things that you weren't super immersed in until you started doing this research and going through the archives. And then I have to imagine that there are a lot of other people who aren't super familiar with that history and these backstories. It's really interesting to see your work and to see that it is so deeply inspired by these archival photos, but then you are also marrying it with colors that are so vibrant. It's meshing this world with that spiritual world that you talk about. And you're adding information to these old photos that we don't get from just looking at them. What originally sparked your interest in the visual arts in general?

I got into art through photography. I took a black-and-white photography class in high school and my dad gave me a camera. He was into photography when he was younger so I picked it up as well. I had a pretty awesome photo teacher — Mr. Mantis. Learning from him was the first time that it blew my mind to look at a photograph. At first, you're like, 'Oh yeah, it's three dudes.' But then the longer we looked and talked about it, all of this background suddenly appeared. It was actually a photo about the notion of exclusivity. So just looking at an image and then deriving meaning that's so much deeper than what you're met with at first sight — that really got me into what I do now.

I know that family is a big influence of yours, but in what other ways do you feel like they inform the work that you do every day?

The reason I became interested in family photographs was because I lost my mom when I was a teenager. So it really came from a place of grief and longing. And sadness and curiosity. I was so young when she died that I literally was just curious about who she was, where she grew up, and what her life was like. She wasn't there to tell me anymore so that sparked my initial interest in the family archive. But the person who was still around was my grandma — my dad's mom. I was interested in memory and the possibility of recreating a memory. So that was kind of how I became immersed in the family archive and talking to my grandma. I asked her so many questions — why did they come? What was it like when you first got here? So I really just had a curiosity about what their experiences were like moving from the Philippines to the middle of America in Ohio.

I do it for my family. I recently heard this person speak who was a first-generation child of immigrants and he was saying that in his family, there were a lot of creative people but they didn't pursue it or they weren't able to do so professionally. And I feel like my interests are also related to that, you know? I've been able to study art and that means a lot to me. I had a painting in the Smithsonian at the National Portrait Gallery, and it was of my grandma. And I was like, 'Dude, Lola's in the Smithsonian!' At first, it didn't really hit me, but then when I went to go see it, I was like, 'Oh, this is about them.' It's not about me as an artist, but it was about this little old lady who lived in the middle of Ohio, volunteered at her church, and made a life for her family. And then she got to be in the American Portrait Gallery. It started to make me think, 'Wait, are we an American story? What does that even mean?' But it was definitely a moment where I felt the bigger picture.

It's a beautiful moment and you get to share it with them. Whenever I talk to artists, there's this recurring talking point of how creatively fulfilling it is to be able to do this as your job. But I think it goes one step further when you get to share it with someone.

I just thought that I was going to be making paintings of my great aunties on their farm in the Philippines forever, and no one was gonna care. That question kept coming up when I first started working with this subject matter. I kept thinking, 'Who's gonna care about this?' It's so personal that I didn't think anyone would care. Which is a sad thought, but, really, it was the refrain all the time. And then I was like, 'You know what? This is what I'm interested in. This is what I'm going to make paintings about. And if I never show anything and people never see it, then I'm happy in my studio painting my great aunties.’ But now, that's different. I don't have that refrain anymore because so many people, Filipino or not, are like, 'Oh, this reminds me of my family.' I had a good friend who told me, 'You're doing the ancestors well.' And I didn't really grow up in the Philippines, but this is where I ended up.

That personal element is what made me so enamored with your work. It's interesting that that was the one thing that you were unsure of because that is the exact reason why I was intrigued. We talked about the way that your family informs your work. In what other ways do you feel your own identity manifests in your work? Or is that something that you step back and choose to withhold in your artistry? Looking at your work now, in person, it seems like you don't aim to insert yourself into the works. Are you just the messenger?

I very much feel like I'm the messenger here. It's a funny question about identity because I feel like as an artist, I ask whatever higher power there is or the bigger picture what wants to be seen or who wants to be painted. I'll literally be like, 'Okay, what do you want me to do today?' I feel like if I'm in it at all, it's my hand and the way that I construct things or choose colors. I'm there in the way that I make figures. So I guess in terms of identity, it's like, yeah, you could identify that this is one of my paintings or sculptures. But beyond that, I don't know. I think that's enough of me in there.

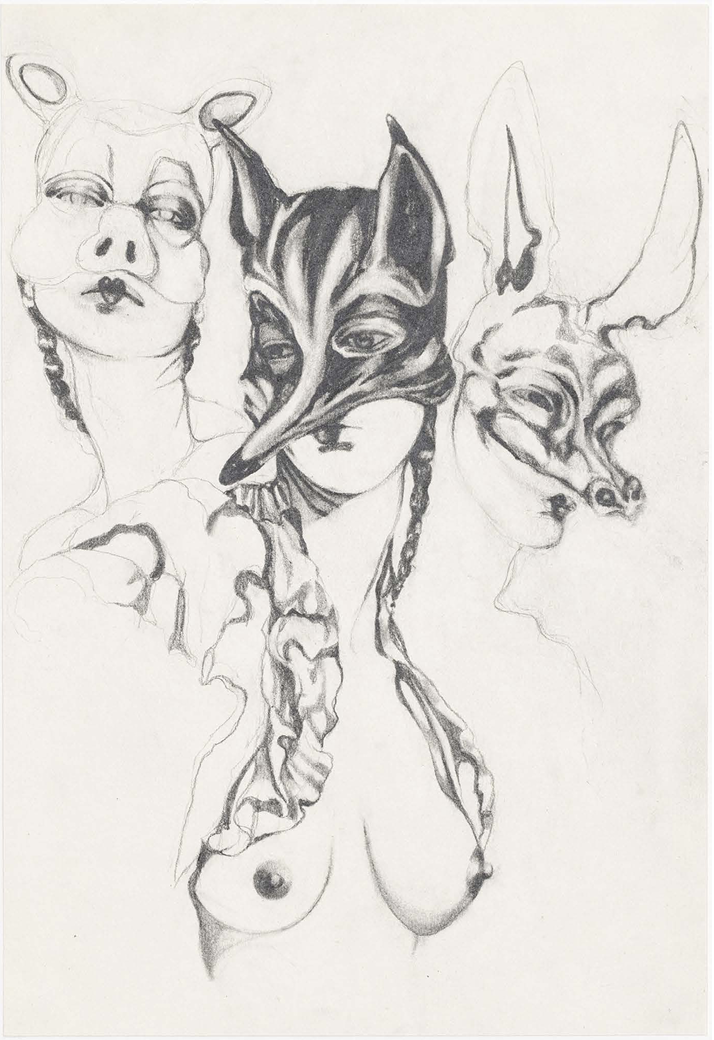

Which is super valid. A lot of artists just want to be the vessel that's bringing these things forth. On the note of color and figure, there's a kind of surrealist, magical element to a lot of your works. Why do you make the color — or even technical — choices that you do?

Color is the best. Sometimes with the big paintings, I'll literally start with a color palette. I think about color as a way to create space. So a lot of the choices that I'm making are to orient the viewer. You can use color to make the space seem like it's receding, or vice versa. And then color combinations enhance the way that that space is working. But as you can see, I work on black paper. It's actually a tan-colored paper, but I use a black gesso instead of a white gesso to start with. So it kind of allows the colors to sit on the paper in a different way. And I think part of that choice is maybe that the material that I'm working with comes from a dark and violent past. A lot of the photos I reference call to notions of colonialism. But then I also think about alluding to different realms. So the colors in a different realm might look different than the way we see color here. I always think about that scene in “Black Panther” where we meet the ancestors and they see colors in a totally different way.

I love that. Through your work, you have learned so much about your culture. But through this use of color and space, you kind of revitalize these scenes in a more contemporary and alluring way. Why do you think it's important to both preserve your cultural heritage, but also present it in this novel way for people who may not be as familiar with the historical references?

I was mentored by the late painter, Denyse Thomasos, who was a very amazing artist. She was an incredible painter but she was a conceptual artist as well. So the paintings weren't just expressive marks, she also did so much research. And it's evident in the work, you know? So I was taught to be an artist that is research-based. She told me, 'You need to become the expert on your work.' I guess what I'm trying to say is the work has to be based in something, and for me, that takes me spending weeks looking through empirical information. It can be very damaging, but also very joyful. Many of the spaces that house these artifacts or these objects are incredible. If I hadn't spent time in those places, I wouldn't have learned what I've learned. And I think being in those spaces, it does something to your body. I definitely feel like a different person after spending time there.

But at the same time, it has allowed me to connect with these objects and it's allowed me to touch them and to transfer energy. Sometimes there are objects that are in those archives that have retained their power through opacity. And that's something that I think about a lot too — we can't know it all. It's a very Western thing, to think that we have to know everything. So for me, it's important to do the research and have those grounding experiences, but at the end of the day, I don't have all the answers and I am exploring these concepts in the same way my audiences may be too. But in terms of presenting my work this way, it's about bridging my upbringing, the oral histories, and my knowledge of our culture. I can't say that I'm an expert on any of that stuff, but presenting it in this way is an opportunity for conversation or for shared knowledge to come up.

The current exhibition is titled Days Later, Down River. What does that title signify to you and why did you choose to label it in that way?

For me, titles are always the last thing that happens. I see the form of the show and then that usually helps me to think of titles. But I do make lists of things when I'm reading and I see something. A lot of the titles come from a special letter that my grandma wrote for me or poems that I've read and short stories. Days Later, Down River is kind of dark and actually came from an article I read about a mountain that somebody died on and they found the body days later, down river. I tend to choose titles that have a pretty open-ended or diverse meaning. It just seemed to kind of work with the show. I find that ambiguity really beautiful.

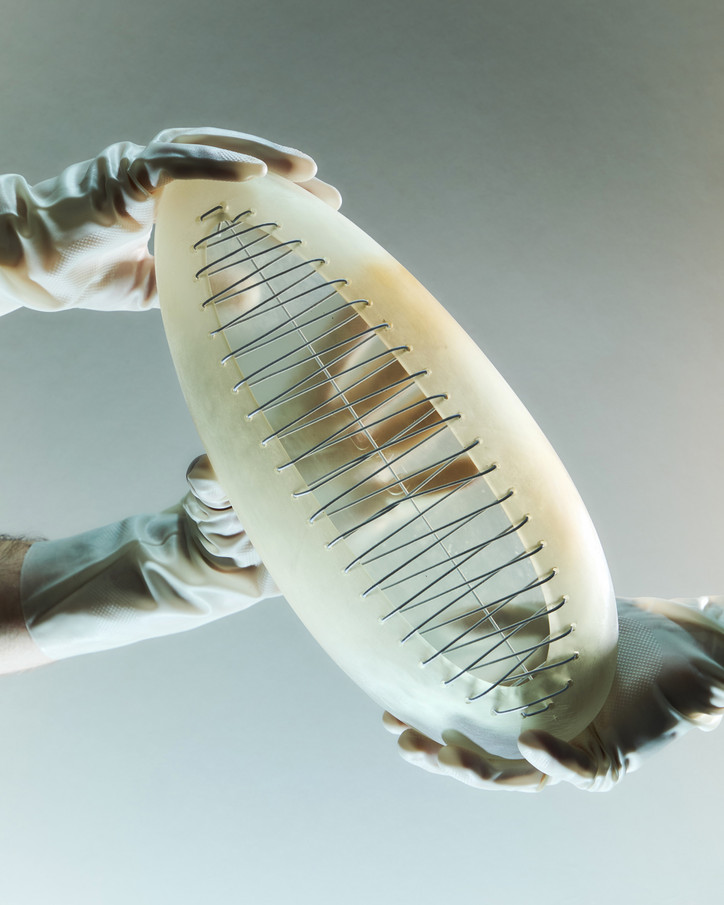

The hero piece of the exhibit is a traditional “banig” loaned to you by the University of Michigan, which is home to the largest collection of colonial artifacts from the Philippines in the world. Why was it important to you to include this object in your show and how do you hope audiences understand it in relation to your paintings?

I'll admit that that front room was a wild card. I knew that I wanted to do some kind of installation in there. I think my intention in bringing the banig into the show was literally to take a piece from the archive out and bring it into a new context. I think about my sculptures as guardians of the banig. I think a lot of people didn't even realize what they were looking at. So I thought hopefully that would spark some curiosity. And I also just think that the object itself has a lot of its own innate energy and presence. So I just wanted to give that a spotlight because when we were looking at a lot of the objects in the space where they're housed, it felt very clinical. That banig, in particular, had been folded for who knows how long and it took three of us to unfold it. The care that was going into all of these archival objects was very moving to me. I was thinking about it as an object to facilitate connection or gathering. It was a way to pay respect to the people who these items were taken from.

I feel that your work will continue to inform itself and the more you learn about your ancestral history, that will add another element to all of it as well. But how do you hope that your work evolves over time as your research does?

I like that question. It reminds me of another mentor of mine who taught me about how to dream. They would say, 'Just close your eyes and think about what you want in five years.' Honestly, I hope my work looks different in five years. I love when I'm surprised by my work and that only happens in the process of showing up every day and doing something new each day. And I hope that my work is surprising to other people. I really hope that it changes because that's so exciting to me. Being lost was the guiding force for this work.

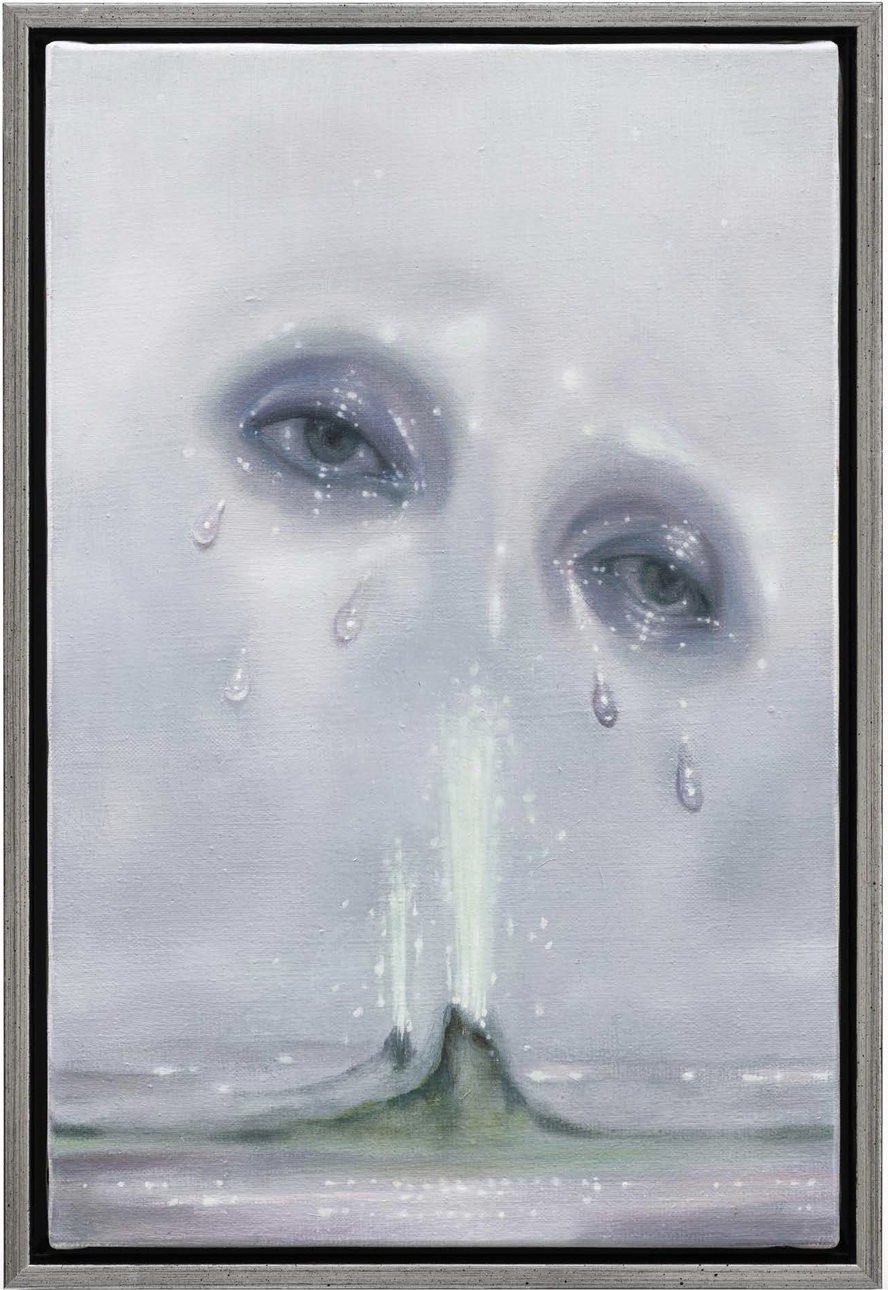

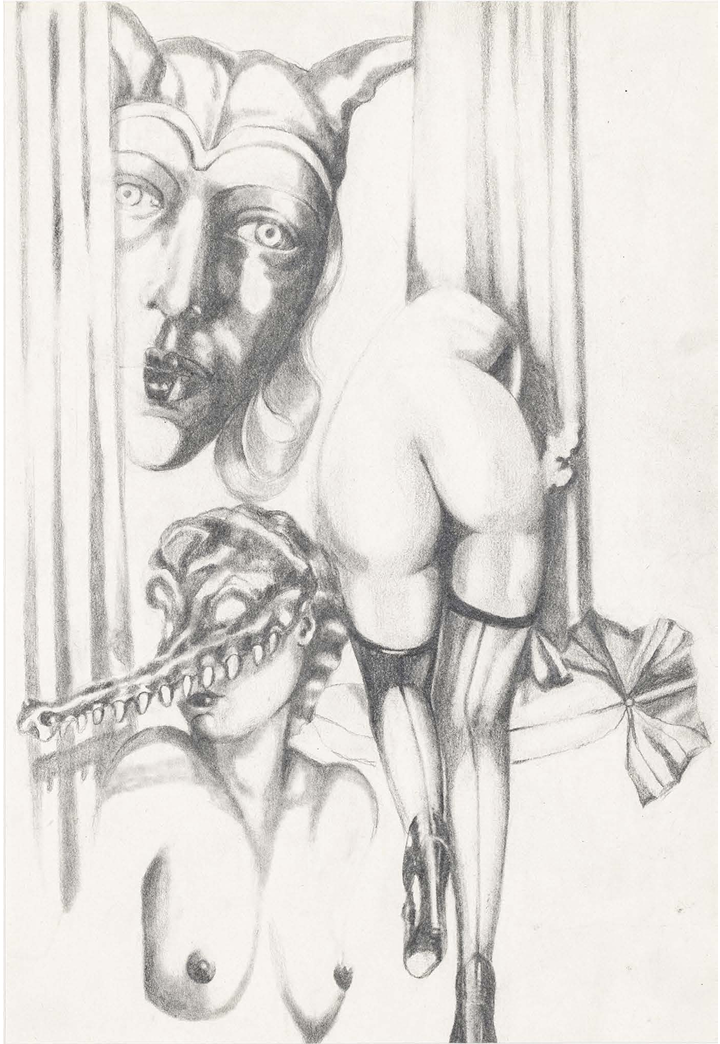

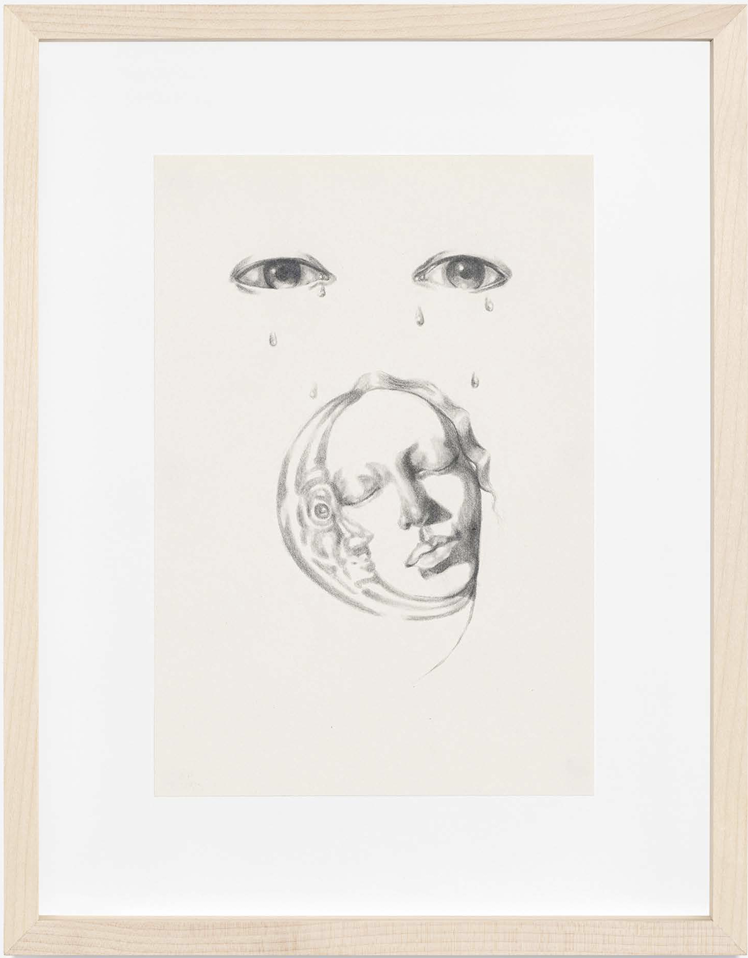

Paintings in Descending Order: The Sleeping Mountain (Cover), Days Later, Down River, It Was Said They Could See Each Others Memories