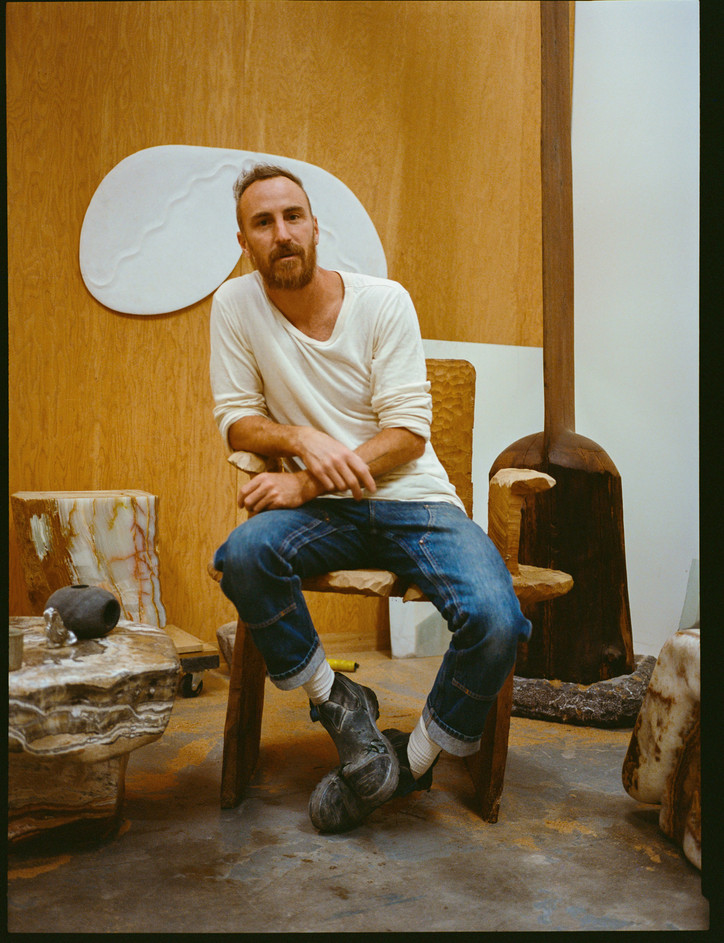

Ian Collings

What made you decide move from New York to Ojai?

It happened gradually. I began spending more time in nature after I met my wife, who had a homestead in the heart of the rainforest in Costa Rica. The contrast between New York City and the jungle—moving from one kind of wildness to another— just became strikingly tangible, and immersing myself in the rainforest rewired my perspective on the world and what I wanted from life. I found myself drawn to spending more time in nature and less in the structured, urban landscapes that once felt so central. When we had our daughter, it became clear that we wanted to leave the city.

Did that transition coincide with your shift from making furniture to sculpture?

For me, the goal was always sculpture. I've just been on a path of realizing that attraction. I love making things and being in an emergent creative process. Whether I’m making furniture or sculpture, I’m coming from the same conceptual and philosophical orientation. It’s like being a musician—someone might play different instruments, but their core artistic vision remains the same.

One key distinction, though, is that a piece of furniture crystallizes into a fixed form, whereas a sculpture keeps evolving in how it’s perceived and experienced.

This thought is very interesting. Could you elaborate further?

I think there's like a need for humans to define and understand things. The sooner we can crystallize something into a solid idea, the more comfortable we feel because we understand it. For example, there’s the idea of “chair-ness”. If someone recognizes a chair, in that moment, the idea of “chair-ness” collapses into something that they understand. But sculpture doesn't necessarily collapse or crystallize in the same way. That, for me, creates room for metaphysical ideas, the sculpture becomes something to play with in order to have a conversation about our relationship to other things.

What is the main conceptual drive that shapes your creative process?

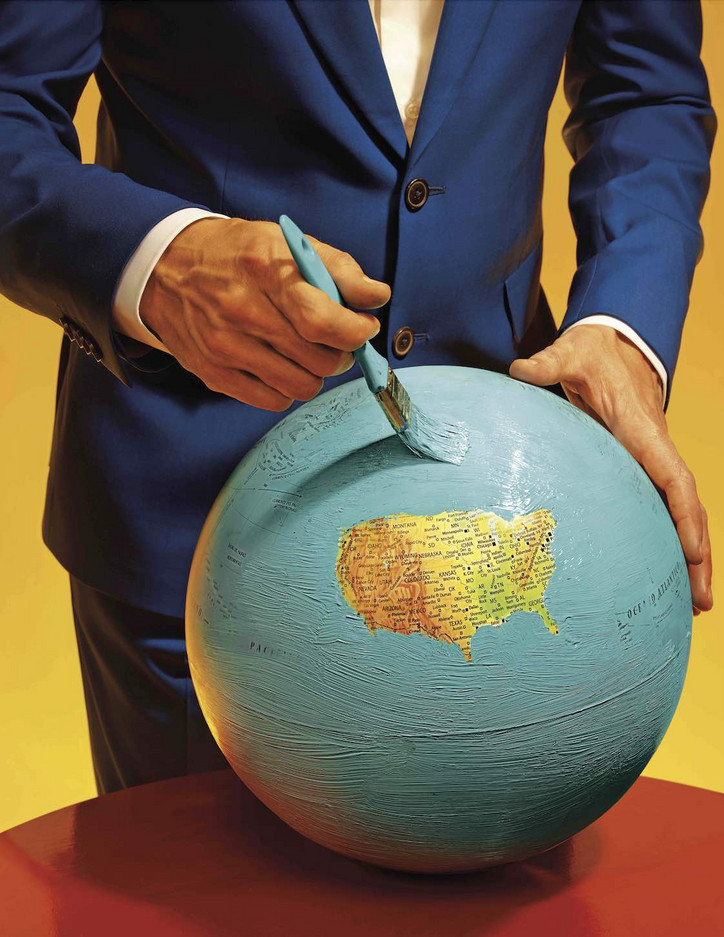

I’m deeply interested in dislocating our human-centric sense of importance. We often perceive the world as though everything—metal, air, and the structures we build—is a human construct, existing solely for our use. This perspective shapes our relationship with the world in a way that feels inherently toxic. It has led us to a point where things seem to be falling apart—and, in many ways, they are.

We tend to see everything through a human-centered lens, viewing materials and places as resources rather than entities with which we can form relationships. But when we truly engage with a place or material, our attitude shifts. And we realize that we are here together, more as a collaboration than a hierarchy. This non-human-centric perspective is central to my work. When I approach the materials I work with, I am drawn to natural elements because they feel alive to me, and it's a conversation that takes place.

Can you give us an example to explain this experience of working with the material?

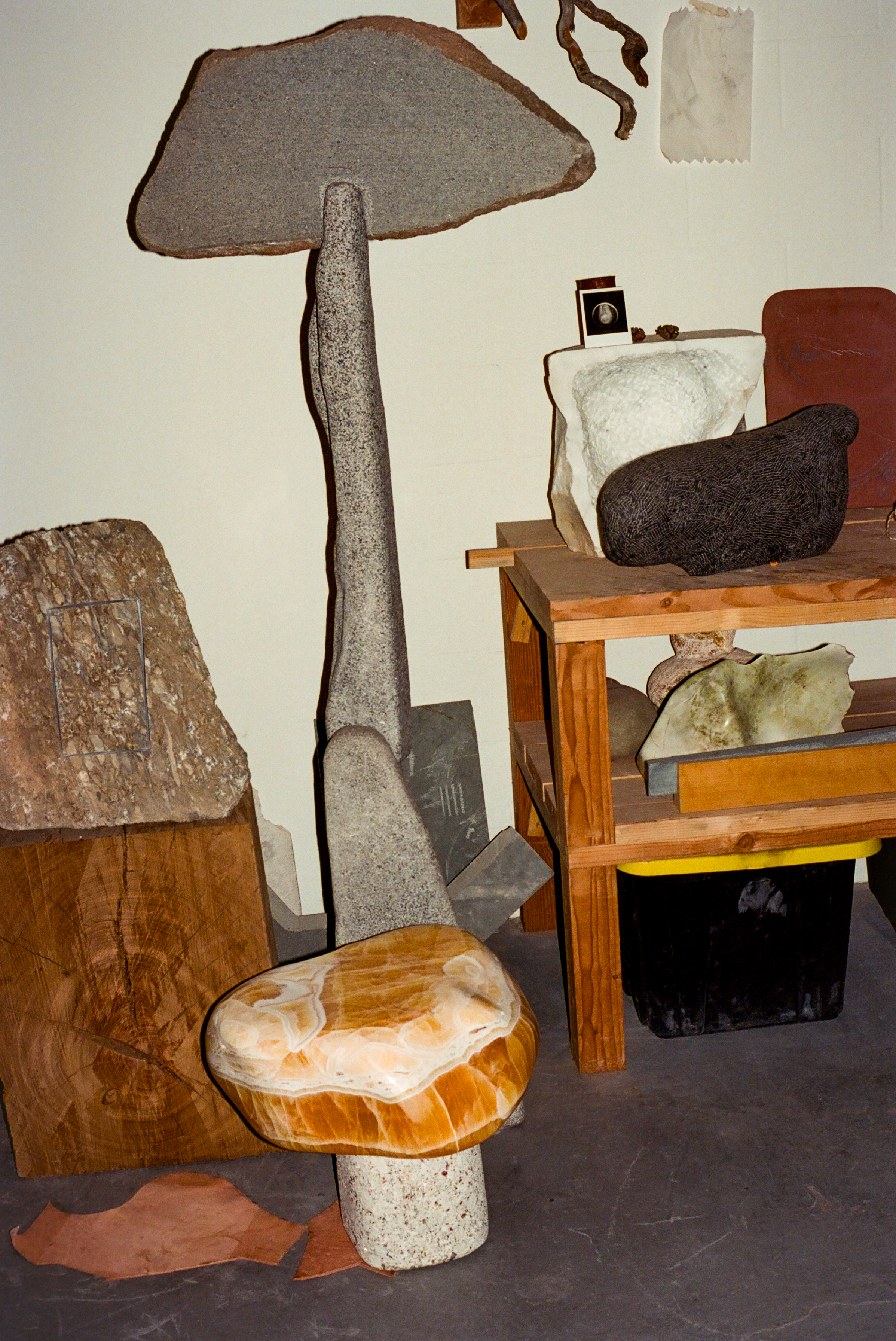

Like stone, it's an ancient material—they’re like images of time. They’re constantly transforming. So the shape of any rock is temporary in that context. The mountain is slowly coming apart, turning back into silt and sand. And I’m just sort of on that journey with it—shape-shifting, expressing together in that moment, which is itself temporary. And that, in itself, feels really dislocated—like to try to find, like locate myself within this like vast abstraction of time.

What you just said reminds me of something Louis Kahn once wrote—when he asked a brick, 'What do you want, brick?' and the brick answered him back.

I love that. That’s so close to me and my process that I literally ask the rock, 'What do you want to be?' I feel like I’m in service to rocks, too—like they’re the higher form of consciousness. They hold energy, matter, information, and structure over vast periods of time, while we’re just these fast burners.

What is the direct feeling of working with stone?

Working with stone feels like I want to impose my will on it. But instead of resisting and going into a different way, it just laughs at me. It’s like, ‘Yeah, you silly human—you use all your energy to pound me into sand, but I’ll just become rock again.’ That’s a different way of teaching. I use every ounce of energy to carve stone, because it's so difficult and so hard. And then, i'm exhausted, yet the stone remains. It's like I use all of my energy, resources, and reserves to try to realize my idea as though it's so important. Then I realized that it's not important. And what's important is the process and the appreciation and the dialogue.

Sometimes I find a stone that already feels beautiful to me. And there's so little that I could do to improve upon that stone, and it just encourages me to do less.

Do you usually work alone, or do you enjoy collaborating and discussing ideas with other people?

I: My practice is very individual, but I don't think i've ever worked alone in the way I collaborate with the rocks, the trees, and the spaces I inhabit. But I do love collaboration and one thing I’ve been trying to do more is utilizing the amazing new technologies to build on the storytelling and context behind my work. Like last summer, I loaded up a truck with all my sculptures, took a film crew out into nature, and placed them back where I found them, capturing it all on video. That’s been an interesting way to bring things full circle in sharing my work.

Have you considered about making a site specific work or like a land art?

I: I think about it all the time. I am really waiting for those opportunities to work with the land in a more intentional way, like creating earth works or moving more in that direction.