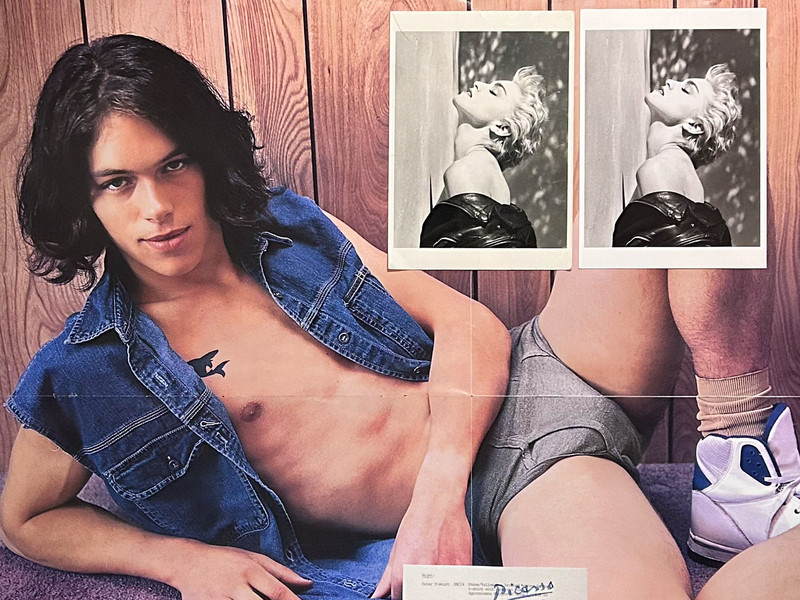

The Joy of Sex

Partial undress in required to enter The Meeting, where a pile of shoes greets visitors, as Bennett has installed a white wall-to-wall shag carpet in the apartment’s living room to accompany what is presumably the gallerist’s furniture: a grey mid-century couch, a stack of art books, and a circular white coffee table on which The Joy of Sex is displayed for visitors to peruse—all so aptly suited not only to the era of the book’s publication but to the form and function of Bennett’s work. After taking off your own shoes and sliding across the soft carpet in socks, you’ll find yourself caught in the reflection of eight mirrors, each etched with a drawing inspired by the publication’s illustrations.

Given the content of the drawings, their re-presentation as mirrors—particularly the largest of the group which pictures a couple copulating on the floor in front of a full length mirror—recalls a view one might encounter in a bedroom outfitted with mirrored sliding closet doors. I used to think that such fixtures were the epitome of a tacky aspirational middle class, installed in apartment buildings with dirty beige carpeting and linoleum countertops for people deprived of good taste or self respect.

A mirror in this context seemed, to me, equivalent to Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation apartment building in Firminy where highly streamlined spaces for an efficient existence proved widely out of touch for the low income demographic that they were built for. Excess belongings, veritable garbage, piled up on the balconies when the individuals that inhabited this modernist building couldn’t afford or maintain the curated lifestyle and Platonic ideal that Le Corbusier believed would simplify their economic and domestic lives.

Mirrored doors, across from one’s bed, seemed to perpetuate the same false promise. Instead of picturing a refined existence, and an effortlessly, permanently sexy self, these doors would inevitably reflect back at the individual the overflowing stuff of their unmanicured existence—piles of clothes, unhoused makeup and toiletries, a stray condom wrapper—and the various bodily experiences that we deny experiencing, even to ourselves.

But I recently stayed in a beautiful apartment, admittedly beyond my means, that had mirrored closet doors across from the bed—and there is now nothing I enjoy more. Bennett’s work only serves to compound this realization. His drawings, like The Joy of Sex, outline various positions and are titled accordingly: frontal, hand work, matrimonial, breasts. While none are remotely surprising—I’m sure any and all teenagers have encountered far more explicit content—they are, simply put, satisfying: bestowing upon the viewer the opportunity to see into the private lives and behaviors of other people, to take stock of what was once societally believed to push the boundaries of “normal” fetishization.

On opposite walls a series of three and four sequences unfold across the mirrors, one picturing a man on top largely obscuring the woman beneath, and concluding, somewhat unexpectedly, given the rather, let’s say, tame nature of the positions, in bondage; and the other chronicling the woman’s “hand work.” Her eyes are at first closed, but in the final image as she rides her partner, his hands on her breasts, she makes eye contact not with him but with us, the onlooker. It is this moment, and this sequence, more than the others, that engenders a visceral experience.

Many female friends have recounted to me an out of body experience during sex, whereby it is not so much their partner but themselves that they fantasize about. At the opening, which proved ripe for admissions of both exceptional and traumatic sexual experiences, a friend recounted an encounter with a too short, excessively hairy man in a hotel room with a mirror on every surface including the ceiling. When I inquired how this could have possibly been “some of the best sex of her life” given her description of the man and decor, she clarified “I only watched myself.”

A sexual experience, any experience, in front of a mirror becomes a performance, in much the same way that an experience in front of a camera becomes a performance, irregardless of an audience. The photographic documentation of Bennett’s exhibition that pictures a frontal view of the works includes a reflection of the camera on a tripod such that it simultaneously becomes an avatar for the voyeur and a threat of your own capture as a participant.

Despite the absence of the camera in the moment of viewing, we anticipate its existence, not only evidenced by our own instinct to take a picture, but by our bodies, which intuitively alter their behaviors to account for the voyeur’s eye. Echoing this phenomenon, the press release sites Jean-Paul Sartre’s “Being and Nothingness,” wherein the author describes the realization that he is being watched while looking through a keyhole at a couple having sex: “When I am aware that someone else is watching me, I experience a transformation. I am no longer simply a being-in-the-world, freely exploring the environment; I am now a being-for-others. I feel myself pinned down by their gaze, transformed from subject to object, as though their perception of me has defined me.” I would extrapolate this for the present to say that we know we are always being watched and, in a culture that privileges images over experiences, we intuitively perform for the phantom camera.

In the second episode of Sex and the City, Carrie’s artist friend, Barkley takes the most pride not in his paintings but the nonconsensual videos he records of his sexual exploits with models. Carrie, and most people, find the practice horrifying, Samantha finds it thrilling and endeavors for the rest of the episode to sleep with him so that she might too be secretly recorded and thus validated as “as beautiful as any model.” She makes it into bed with Barkley, but when she remarks about the absence of a camera, he says he only tapes models, though eventually consents to make an exception. So as the little red light turns on, Samantha turns her attention to the camera and makes eye contact with us, the viewer.

Samantha’s performance—like my friend’s and, I would assume, that of most women—is not so much for men, but for herself. The men are there, yes, we need them to complete the fantasy, but ultimately we are most turned on by ourselves. The anticipation and desire for one’s own image encapsulated by this scene seems like the logical evolution of Lacan’s mirror stage, which asserts that around six months old a child can first recognize themselves as an object in a mirror as opposed to fragmented collection of experiences. The ensuing self-alienation unlocks a libidinal desire. It is, you could say, objects rather than subjects that turn us on. Samatha is most compelled by her own objectification, so is my friend, and, admittedly, so am I.

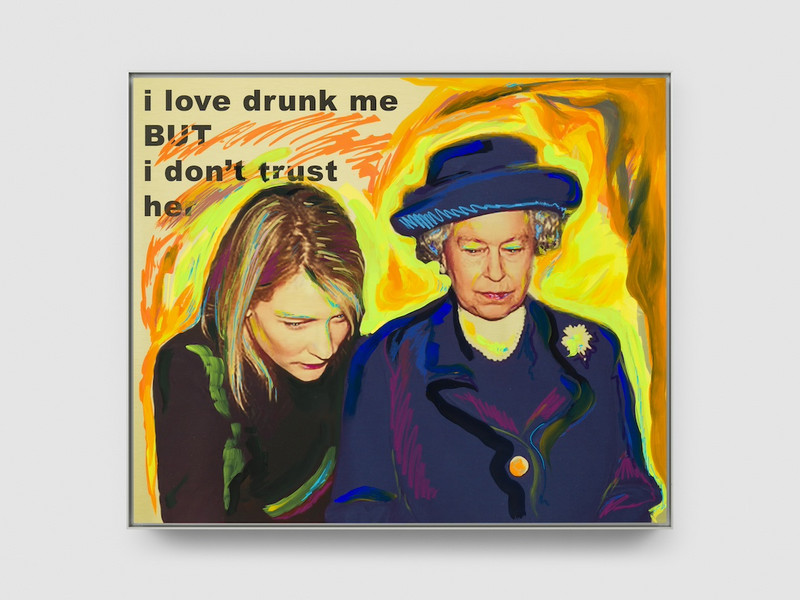

Bennett has explored a similar binary prior in a video titled Subjects and Objects (2022) wherein found footage chronicles a wide range of instances in which people have developed emotional attachments to objects: falling in love and, even, expressing a desire to make love to them. While he examines in particular the affective presence we project onto objects and their ensuing double ontology as both inanimate stuff and pseudo-sentient characters, when considered in conjunction with Lacan’s mirror stage and the fact that we must all confront our own objecthood, the emotional attachment to objects exhibited by the individuals in Bennett’s video becomes far less surprising or abnormal. In many ways their attachments are no different than our own—we all love objects.

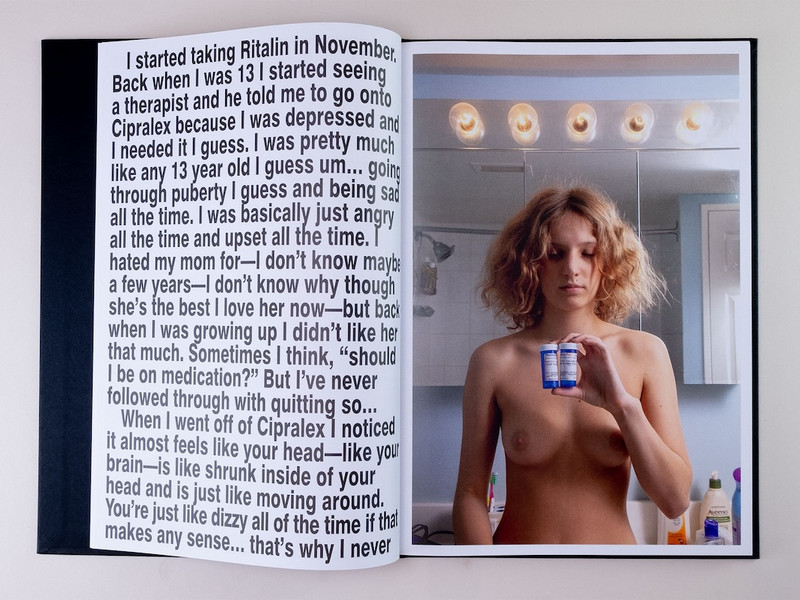

If The Joy of Sex was once evidence of a sexual revolution, it seems almost fitting, whether intentional or not, that Bennett chose some of the most tame illustrations at his disposal. A reflection perhaps of our present, as author and former sex worker Charlotte Shane writes in a recent essay in ArtReview that "We may dwell in a pervert’s paradise," referring to the proliferation of content at our disposal: OnlyFans accounts, dating apps like Feeld and Grindr, endless free porn, "but no one invokes the specter of sexual revolution or utopia, not anymore. We venture few dreams for the future, erotic or otherwise." What was once explicit may now be banal, but that doesn't mean that we live in a more sexually liberated world: Shane chronicles the criminalization and curtailing of sexual and reproductive rights as well as the personal and activist responses to these trends that increasingly take the form of abstinence and, in the case of the 4B movement, swearing off men altogether.

My own sexual fantasies are politically incorrect. But while men might welcome this, women recoil, so I have become loath to share such thoughts openly and am by extension a participant in our collective self-censorship. Bennett's work may be further evidence of this inward turn: the sex we have is more often than not with ourselves and our reflections, whether that be in the blacks of your computer screen while on PornHub, or the mirror across from your bed. What he provides though, via his doubly ontological gambit—that reprises a device for introspection as one of public performance and consumption—is a prompt and maybe, even, an invitation.