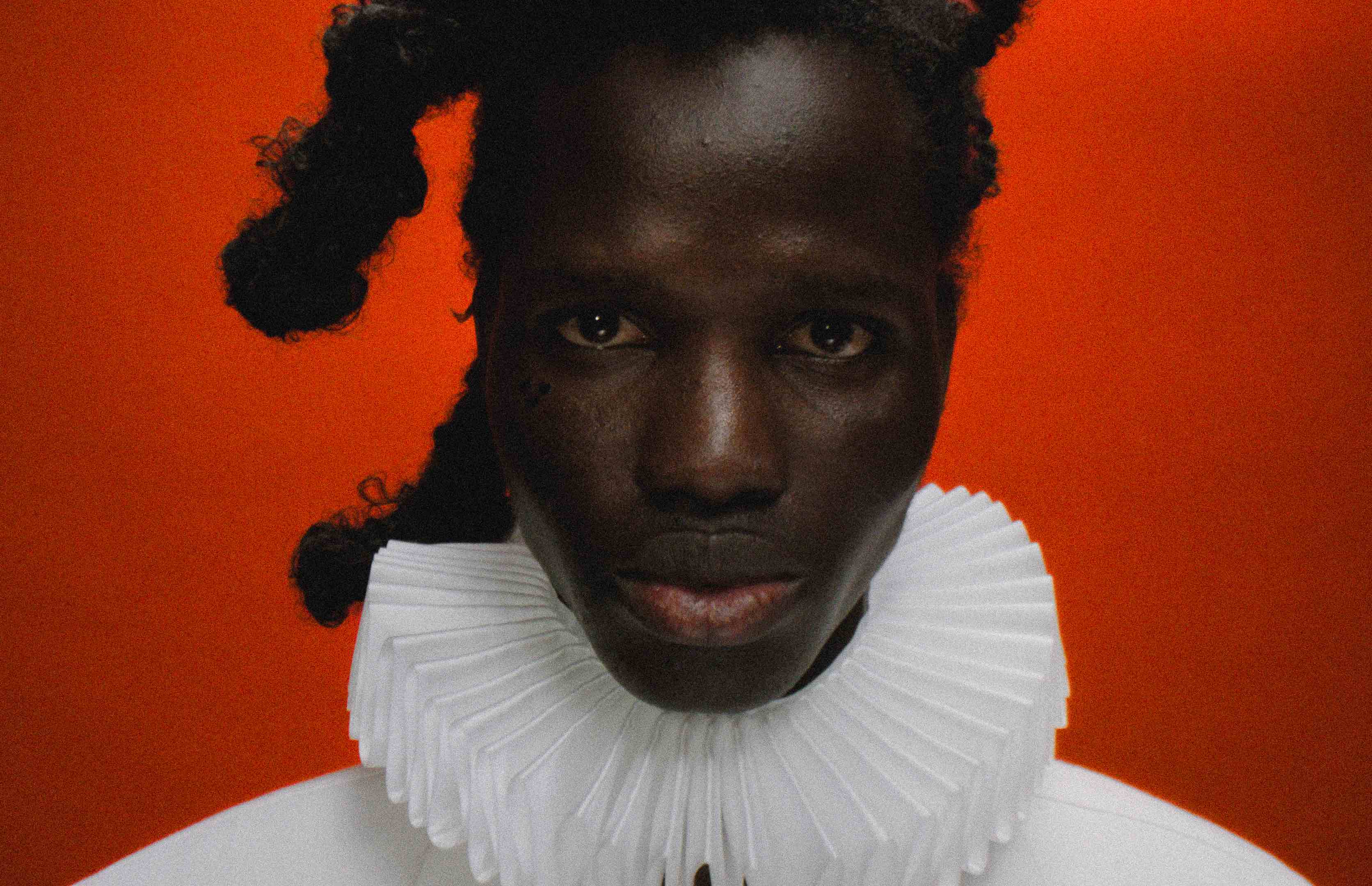

Investigate with Derrick Adams

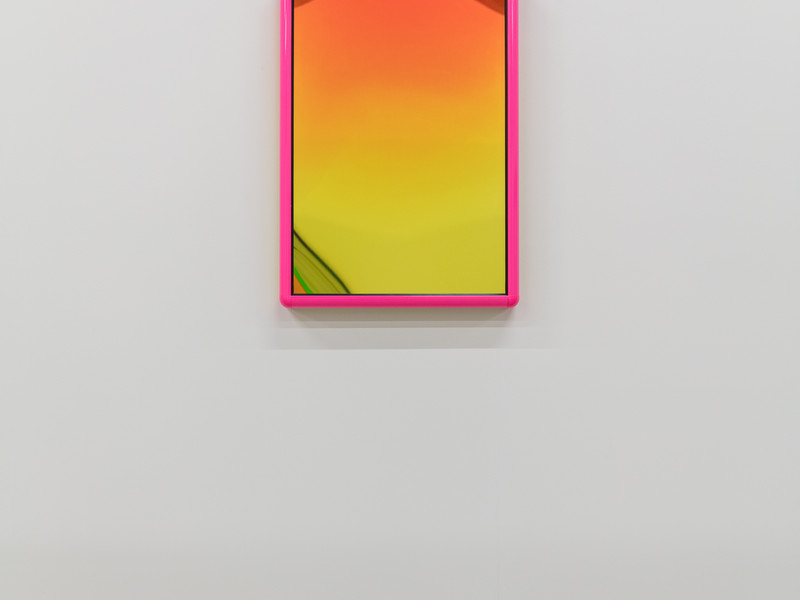

Reminiscent of Jeff Koons's "Celebration' series, Fun Time Unicorns is inspired by Children's toys and blow-up balloon animals. The iconic Unicorn, represented in the interactive sculpture, is a continuation of the artist's celebrated Floater series, more specifically the piece Floater 80 (Self-Portrait). The floater series features Black people relaxing and enjoying leisurely moments atop inflatable pool floats in residential swimming pools. The black unicorn figure was birthed from this series, then manifested into a life-size pool float, and eventually into its current iteration as Funtime Unicorns.

The unveiling of this sculpture at Rockefeller Center coincides with the launching of the artist's Edition business and an accompanying website where consumers can purchase editions of the artist's work directly from his studio. As the sole owner of this business, Adams is taking control of his product. The Funtime Unicorn's edition will be similar to the sculpture in Channel Gardens and will be released as an edition of 30, with 10 AP. With this endeavor, Adams is exploring avenues outside of the gallery models to engage collectors and fans of his practice and continue to expand his footprint in an ever-transforming art market.

Emann Odufu - Nowadays, a lot of artists are talking about showcasing black people in leisure as a form of protest. This is a concept I came to through engaging with your work. The first time I saw your work in person was the Floater Series, which showed at Project For Empty Space in Newark, NJ, in 2016.

Then I met you a couple of months afterward in Philly, touring the public art installation "In Search of the Truth" when you were doing a mural for Philly Mural Arts. This past year, I've been writing and interviewing various artists, some of whom have taken great inspiration from your work, specifically this idea of celebrating black leisure and play as a revolutionary act. So, I'm curious about how this concept of leisure and play became a focal point in your practice and what were some of the things that inspired you to pursue this concept.

Derrick Adams - Probably starting in 2010, ideas around this subject matter and theme came into a more refined voice. It came from a desire to see a certain level of normalcy depicted in black life in art. I was interested in how I could play a role in establishing that visual narrative through my creative output. I was looking around at the overall landscape of what was being made by black artists and the conversations surrounding the work of my peers and what they were interested in. I was thinking about my position as an artist and what I could offer through my perspective of looking at black culture in a way that was not as easily accessible at first glance. When you think about leisure or the idea of normalcy or relaxation, that doesn't always trigger such a visceral response as images of protest or politics.

Images not showing black people pushing against something or depicting "the struggle" automatically refers to the idea that it may not be political. Because what I decided to create was not a dominant visual voice at the time, I felt compelled to go in that direction because I felt that it should be more of a prominent conversation within contemporary art. Especially looking at the younger generation and how to position them to be prepared to deal with society on their terms. I was thinking about what the black people I know do daily and what that would look like in art. As a black community, we have always been involved in protests or some level of socio-political unrest and challenges. I think it's important for creative people to look at those struggles and present that to the world. Still, I also believe there is a place to broaden and even complicate Blackness's narrative by introducing other ways of looking at us.

As Americans, we can't help but be part of this idea of the American dream. You work, then you enjoy the benefits of it. That could mean a vacation or some level of reset. Those things as a Black person are amplified even more as a political position. So my constant motivation in my studio is how to present these things that are not very difficult to conjure up and that I find through looking around me and tapping into my community. I tap into it through understanding the people around me and all they have contributed and received from black culture. I'm constantly thinking about putting that into the world and giving the future generation the option to look at art from that perspective.

EO - I read somewhere that the Floater series was partly inspired by photographs of MLK and Coretta Scott King on vacation in Jamaica. Why were these photos so significant to you?

DA - I just started thinking about political figures like MLK, Malcolm X, Coretta Scott King, and Betty Shabazz. I started thinking about them as individuals, mothers, fathers, or brothers and sisters. I started thinking about the things they did between the struggles and the protests. Through research, I began uncovering images of Malcolm with swim trunks and then of MLK and his wife on vacation in Jamaica.

These are not images presented at the top of any Google search of these public figures. So that automatically motivated me to dig deeper. To know that these individuals, who are considered the pioneers of civil rights and who made major sacrifices for us, also had moments of reset and Relaxation while still being incredibly important figures. This cemented everything I think about when I think about the importance of representing people at leisure. It is a significant way of looking at the multidimensionality of black people.

EO - You mentioned that a lot of your work is inspired by your experiences and the people you've met. I read that your first gig was being a teacher at an elementary school, even before you went to Pratt. Do you think that experience of working with children translated into the formation of your practice?

DA - Yeah, of course; I think being an educator - because I also teach at Brooklyn College now - makes you aware of the systematic structure of learning. You understand things from a very fundamental position. You start being aware of what's in the textbooks, the illustrations, and how current the publication is. You're presenting these things to young minds at a very particular time when these are their introductions into American culture. These things also sparked a lot of my interests and direction in art making because I realized that you could redirect and reroute various conversations that spawn from visual language and visual iconography as an artist. Especially if you think about how you want people to view themselves or the community around them. So, teaching gave me a sense of how people see, or the way people understand, based on access or lack of access to images or cultures that will help advance their understanding on a broader level.

As a visual artist, there are things that I want to see as a black person in the world when I go to exhibitions at a museum or a gallery. There are images of Black people in certain settings that appeal more to me. When you think about figurative works containing the black figure, it is more about imagination. It's about really imagining a place where you are in charge and where you are the primary subject, and where you can create any illusion of reality that you want, and this is where you can do it. Maybe this reality you're conjuring up could be happening somewhere, and it could be influential in some ways through your imagination. Putting it in the world might make things exist in a way you envision just by putting it out there. Visual art overall is such a tool of higher learning. The way it operates, you don't even know you're learning. It puts seeds in your head in your brain that grow into other ways of looking at yourself and looking at people you encounter and people who may or may not understand the reference points that you may be putting in the world as an artist.

EO - Can you elaborate on this symbol of the Unicorn in your work, specifically its connection to the Floater series?

DA - A lot of my work has evolved out of ideas that spawn from other ideas. That's how I work. I don't want to overthink the outcome. The Unicorn figure came from a continuous process within the Floaters series when I was first working off images of actual floats. I would buy them from the store and use them in drawings. So, it was more about accuracy and capturing the absurdity of the objects you could buy. I didn't want to make a float because it was more about using the commercialism of what is attached to the actual images in context with the figures. As I started working through it more, I realized that with the direction the work was going, the idea of fantasy became more of a possibility. This is because I was drawing these cartoonish objects. One day I was making a white Unicorn float, and I just said this Unicorn is not even real, so why does it have to be white. It's a mythological or even made-up image. No one has ever seen one, so why is it white? Why can't it be something else? So, the black Unicorn came out of the idea of just seeing something one way and having the ability as an artist to change the narrative simply by changing the color tone. That slight change brought in this idea of politicizing the Unicorn itself just by changing the color of the Unicorn from white to black.

Eventually, I realized that the Unicorn could operate in many different iterations. First, it was a small sculpture, and now it's a spring ride. I think it's almost become a branding thing for me, as a way of reflecting who I am or what I believe in. The Black Unicorn became a symbol of Blackness as a very magical and mystical thing with many mysteries intertwined with what you perceive it to be. The Black Unicorn is very freeing for me to use repeatedly in many ways because I feel like it's more of a declaration for me as a maker, and so I'm always thinking about ways to incorporate it in different forms.

EO - As you know, I went out to the unveiling of Funtime Unicorn at Rockefeller Center and was able to experience the spring rider firsthand. I was very impressed with it. However, this is also the launch of your editions business. To me, I see a connection to Jeff Koons in his Celebration series, specifically the usage of blow-up balloon animals as a source image. I'm curious whether this is something that you were thinking about as you were conceptualizing this edition of Fun time Unicorns.

DA - You cannot overlook the contributions of Jeff Koons, specifically the way he has manipulated objects to appear light which are heavy, and his examination of the American fixation with consumerism and identity politics as it relates to a consumer object. He examines who that object is made for and how it operates within society and in a public space. His public works always have a level of fun and excitement, which I am personally interested in as an artist. However, when I'm making something and putting it into the world, I do expect to have some level of response or engagement with the audience because I'm putting something in a public space.

EO - I'm curious about what factors in the art world, or even personally, led you to decide to start your Editions business at this moment.

DA - I saw it as a perfect time because there are so many ideas that I've had on my list of projects that I want to accomplish. The editions business being one. I like the idea of transforming my ideas into paintings and into things I make that are wearable. Things that I can transform from work on walls to something that people can engage with physically, like a toy or playground equipment. I like to think about accessibility as an approach to engaging with my work. So, whenever I have an opportunity to make an edition, more than one person can have it. More than one person can engage with it. I feel like that's a part of my practice and equally beneficial to me as a maker.

EO - So, I know from prior conversations that community is at the center of your practice, which, to me, is fantastic. I've heard you have a couple of nonprofit organizations you started in Baltimore. Can you tell me a bit more about those organizations?

DA - I believe in community and making art more accessible in many ways. About three or four years ago, I became interested in establishing some nonprofit organizations in Baltimore that relate to ideas surrounding my work. Leisure is one of them, and archiving is one of my interests when making a body of work. So I established the Charm City Cultural Cultivation, a nonprofit organization with three sub-organizations.

One is the Last Resort Residency is a reset, leisure, and social engagement space with a residency component and studios. It is a space for black creators and visual art, literary, culinary, and other forms of creative output to be invited here for a month to experience a space for creativity, community, and social engagement. We hope to launch it next year at some point. We're still establishing the structure for it.

The Black Box, my digital database, is another organization focused on helping the citizens of Baltimore archive their data that family photos, or objects that can be transformed into digital files that will be stored in the database. This is something that we won't own. We will just be the gatekeepers of the data. It's also a space for artists who have done work within the black community around digitizing archive material can have open discussions and workshops with communities that help them understand the importance of archiving, how to access it, and how to share it. The programs will focus on bringing people to the space and creating a community surrounding the database that will have ownership in some way of its direction.

Zora's Den is another organization I started in Baltimore, a Black women writer's circle. They publish anthologies every two years. They just published the second issue, Ironside. Zora's Den is also a workshop format where women come together and edit their writings. Then, they have readings, and they publish their writing.