Knowing the Past Only Informs Our Future

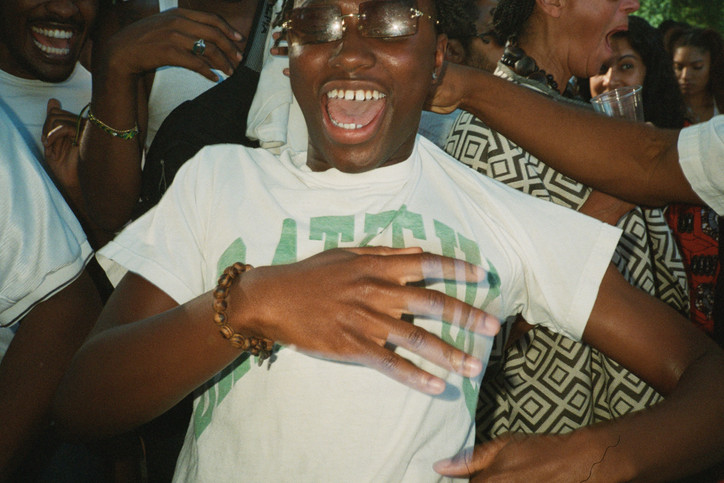

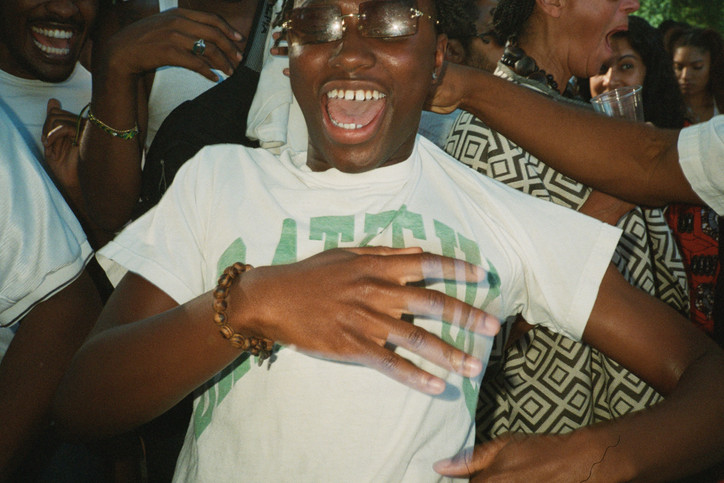

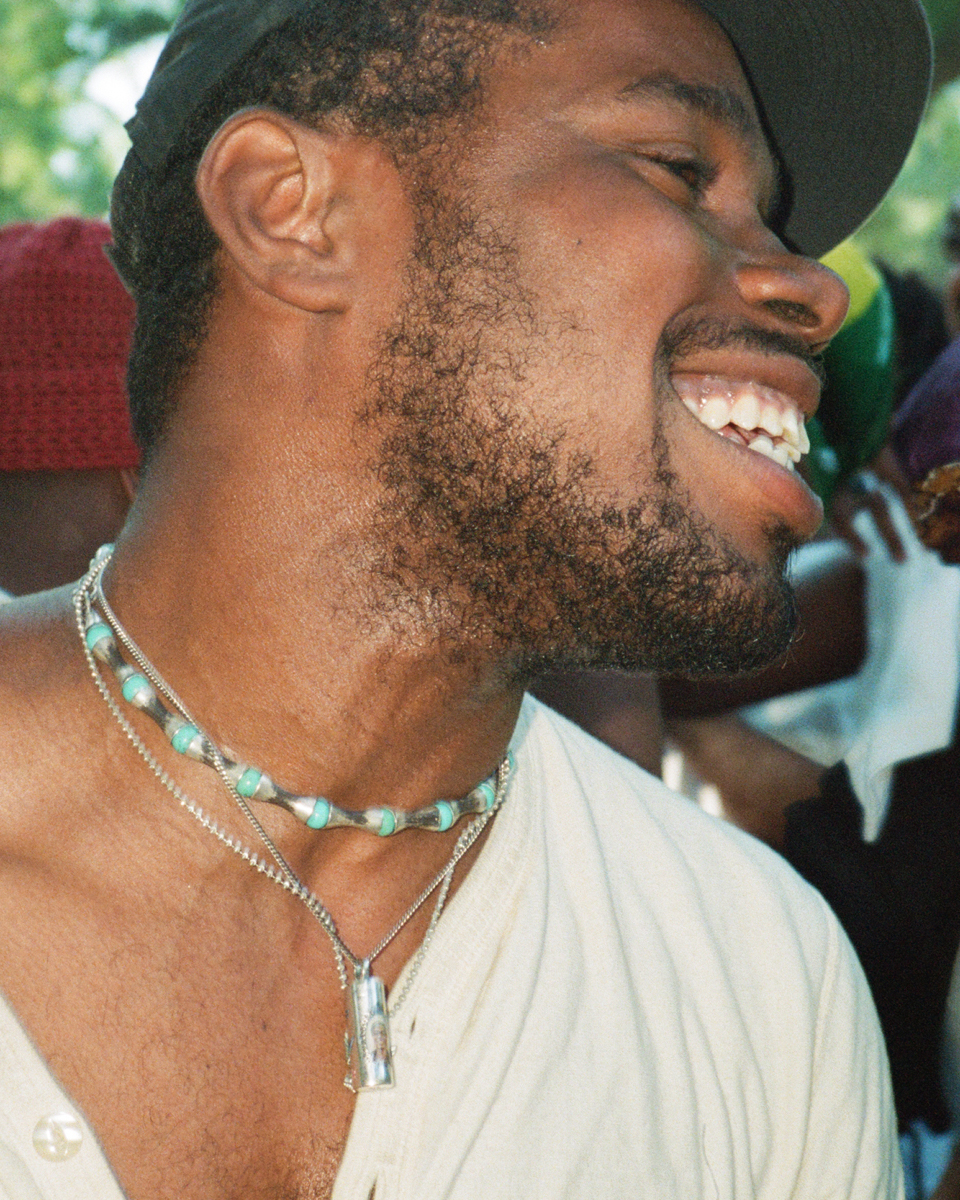

These images were taken in Fort Greene Park, Brooklyn, NY on the June 19th, 2022 in celebration of JUNETEENTH.

Stay informed on our latest news!

These images were taken in Fort Greene Park, Brooklyn, NY on the June 19th, 2022 in celebration of JUNETEENTH.

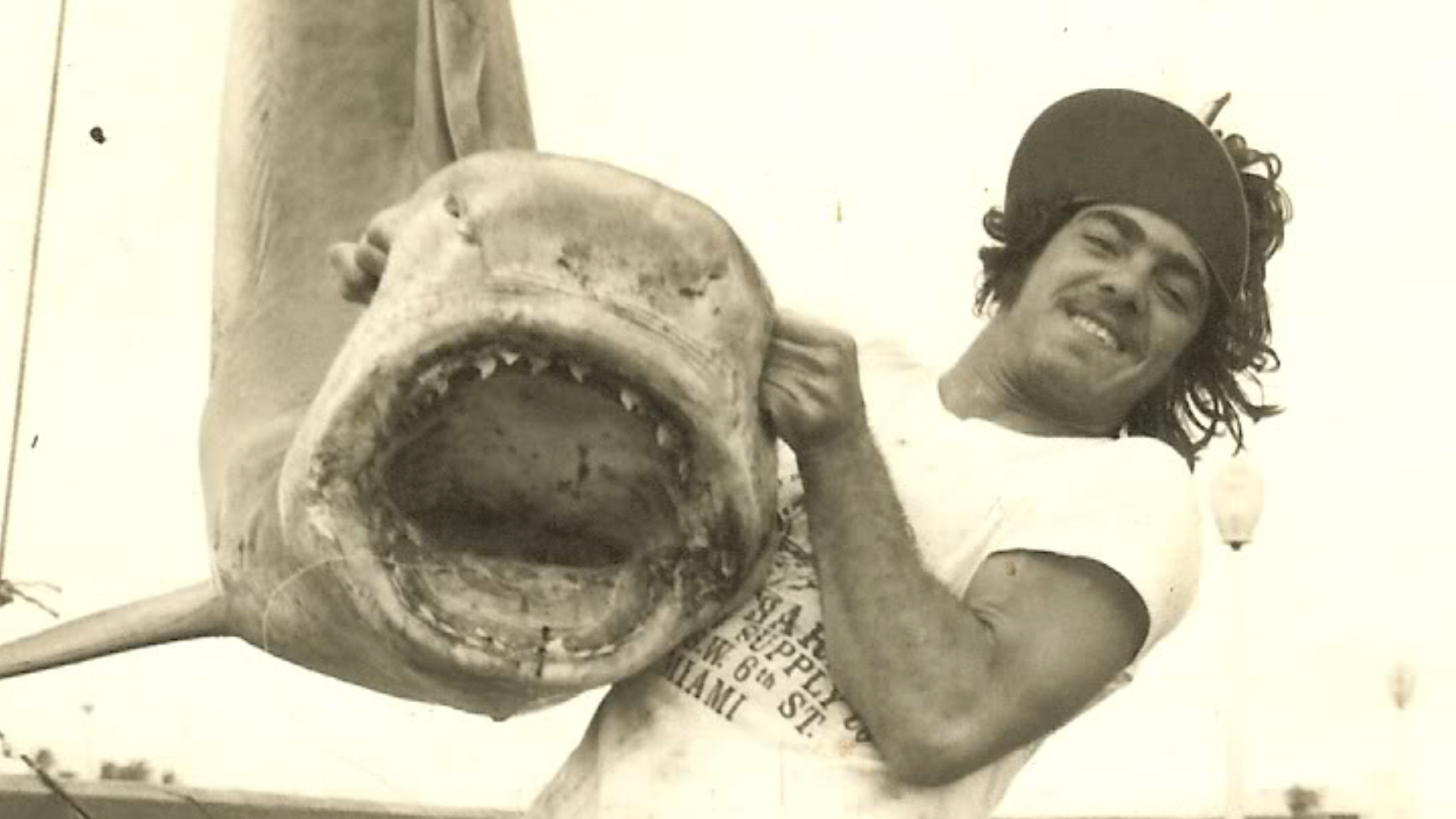

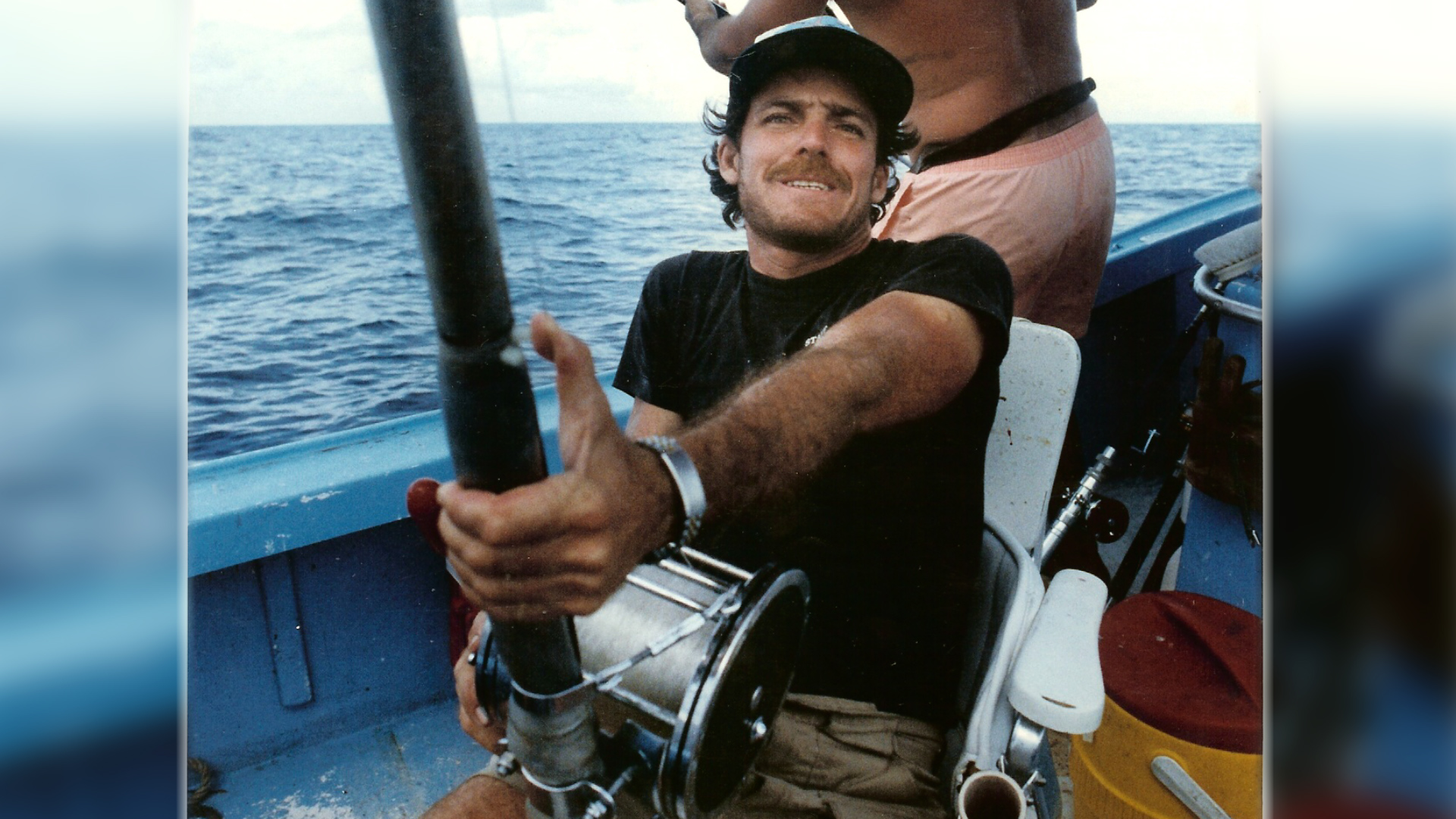

There’s also Shannon “Seaweed” Bustamante Jr., who grew up fishing alongside Rene and his father Shannon “Seaweed” Bustamante. During interviews, he’s seen sitting next to his own son, Dante. We cut between Jimbo, Seaweed Jr., and other locals who knew Rene, who knew South Beach, pictured alongside archival footage of Rene catching and swimming with sharks, interspersed with interviews from local reporters. Shark fishing, or sharking, as a sport, is not something people are generally familiar enough with to think that it would have its own Michael Jordan. But for those who knew him, like Jimbo, Rene was Michael. “I’ve taught a lot of kids, and they become good,” he says, back on the pier, the spitting image of a salty and seasoned sharker. “They become better than me. And Rene was one of them. [He] became one of the greatest shark fisherman in the United States,” Hammer says on the pier. “He proved it every day… he died proving it.”

I grew up in Miami. I attended Marjory Stoneman Douglas Elementary School, named after the journalist turned asexual environmental crusader, and then I went to Miami Dade College for film for two semesters before dropping out. That’s where I met Robbie Ramos, somewhat embarrassingly. The short I made during the first semester somehow made it to the Miami Film Festival student competition. Possessed by the delusions of grandeur that come with being a writer and the God complex of a 21-year-old, you would have thought I was on the red carpet of Cannes the way I acted like my shit didn’t stink. I got wasted at the open bar reception at The Standard on opening night off a pitcher of sangria and tequila shots. I left halfway through Jason Reitman’s “Tully” at the Olympia Theater in Downtown, but it didn’t matter to me. The only thing that mattered to me was the Cinemaslam, the student film screening the next morning.

It was at the Tower Theater in the heart of Little Havana on Calle Ocho. No part of me expected to win. Everyone else was showing thesis projects, but my film was done as part of Film Production 1, which meant we didn’t use sound equipment and couldn’t leave campus. It was exactly what you’d expect in a student film screening. The film that stood out belonged to Robbie and his producer Pedro Gomez. It was the short film version of what became their feature documentary, South Beach Shark Club. I was blown away. I’ve since found that it’s rare to feel that in a theater during a screening.To think something a peer of yours has made isn’t just interesting or technically sound, but also so fucking cool, is special.

South Beach Shark Club won Cinemaslam, of course. Immediately afterward, I went up to congratulate them. To me, they were rock stars who just killed a set. I befriended them. And for the rest of that weekend, the three of us partied like the college students we were. It’s a tradition we’ve more or less continued anytime the three of us find ourselves in some stuffy ‘Miami filmmaker’ this-or-that, which happens more often than you’d think. Between us is a type of kinship, a mutual sense of being an outsider.

When I moved back to Florida, I hit up Pedro and asked if he and Robbie could take me fishing to write about the South Beach Shark Club. They said yes. On this particular Tuesday, it was 86 degrees and blazing hot — but still, not yet humid. A perfect Miami day. We weren’t sure if we’d be able to catch anything, but nevertheless, I’d finally get a feel for what they’d been doing for the last six years.

I. The South Beach Pier Rats

South Beach Shark Club as a documentary is broken down structurally in chapters, like all old fables. It’s a fitting device, because Miami is ultimately a place built on myth.

If you stay on South Beach long enough, you’ll find yourself stepping into a time warp where nothing is new and nothing is old. Miami’s history is in a temporal space trapped in a haunted Art Deco hotel. No one is from there — even myself, who’s from here. A multi-generational family like the Bustamantes is rare. That transient nature adds to the myth, though; it could be 2024 or 1974, and yet it’s still a place where the Latin American and Caribbean political diaspora, the Jewish, Russian, and European emigres, beach hippy weirdos and junkies, artists, and misfits alike swelter together. By mid-June, those who've been crazy enough to make Miami home are desperate enough to escape their suffocating reality of swamp humidity, discovering refuge by haunting the nightclubs of Collins Avenue by the Art Deco Motels, milling about like wispy tipsy ghosts.

After sunset, when everyone else leaves the beach, drunk and pink, a different group of strange characters come out to play. Despite her changing nature, there are points of focus in South Beach that remain unmoving through all the burn and blur. Mac’s Deuce, open since 1926, and owned and operated by Mac Klein from 1964 until his death in 2016, is one. Joe’s Stone Crab, open seasonally since 1913, is another. Those points of focus are all interwoven into the tapestry of the beach’s history, its legacy. Along the sand at night, there lives those who subsist on those excesses and revel in the thrills the beach has to offer: the shark fishers.

Rene De Dios caught his first shark when he was fifteen, in 1971. Not long after, in 1973, the film rights for an unreleased novel by a man named Peter Benchley were sold to Universal Pictures. That novel, Jaws, came out in 1974. Steven Spielberg’s beloved adaptation came out the next summer, in 1975.

After that, fear and fascination with sharks became monocultural. Shark fishing competitions began to take place along the coast, by either land or boat. De Dios, depicted in his early twenties, had assembled a crew nicknamed “The South Beach Pier Rats.” Together, as displayed through the documentary's archival footage, they dominated those tournaments throughout the late seventies up until the mid eighties.

This period ended semi-abruptly in part due to the influx of Cuban immigrants with the Mariel Boatlift in 1980, which, among other factors, induced rising crime rates in South Beach. As the documentary explains, the pier where Rene and South Beach Pier Rats competed went into disarray, and was demolished in 1984.

Tuesday, May 7th, 6:05PM:

It usually takes about four hours to drive south from Central Florida to Miami on I-75. Robbie picks me up in a minivan on 14th and Collins, with Pedro riding shotgun. Robbie is already barefoot, and the two of them are railing cigs and gleefully blasting Jim Croce as we make our way. It’s golden hour and I’m laying on the floor in the backseat, letting the breeze hit me.

Once we park on 30th and Collins, we stop to get some supplies, before heading down to meet up with Seaweed Jr. We go to the mini mart for 3 six-packs of Stella Artois and a couple of packs of yellow American Spirit cigarettes, all the supplies we needed for a day spent attempting to do something objectively silly: catch some sharks.

II. The Great Shark Hunt

The second act of the South Beach Shark Club documentary begins in the present with the narration of our very own Seaweed Jr. He passionately discusses the importance of keeping the legacy of his father and Rene alive. On an overcast day, he’s filmed alongside his son, Dante. Off the bridge, they hook a small reef shark.

Back in 1984, the demolition of the South Beach Pier forced Rene and the South Beach Pier Rats to fishing start from bridges. Like rats, they subsisted because they could adapt. Still, the wave of shark fascination had peaked. Younger competitors were few and far between, and there were less competitions due to the rise of animal rights activism (shark fishers in this time did not practice catch and release). This loss darkened Rene with frustrations. Despite this downturn in his culture, in the 1990s, Rene was said to have caught a great white shark off the shore of the Bahamas. This would’ve been the fishing maestro’s first great white, and as the myth goes, the weight of the shark caused the boat to begin to capsize. The captain is said to have wanted to cut the line and save the boat, but Rene apparently threatened to kill him if he did. The boat sank. Rene supposedly didn’t retain the great white. We’re shown press clippings about a boat sinking in the Bahamas due to a shark. Did it happen? Captain Louie, interviewed in the doc, was with him.

He says it happened. It’s certainly one hell of a story.

Tuesday, May 7th, 7:13 PM:

We joined Seaweed Jr on the beach off 36th. He is accompanied by his son Dante’s youth football league, the "Shores Spartans" — for whom Seaweed Jr is the assistant coach — and their families, as well as other fish enthusiasts. They’re setting these huge gauged fishing rods in the sand. It’s supposed to take a while, and we don’t even know if we’re going to catch anything, try as we might. Part of the reason it took several years for the feature film to get made, they tell, me, was the slim chance of catching a shark on schedule for production in a place that rains 70% of the year.

Robbie, growing up on the beach, learned to shark fish himself from his father and uncle Jorge — who recently passed away and was also featured in the documentary. He met Rene when he was growing up in Florida, as well as Captain Louie, the head of the Shark Club and the captain who witnessed the Great White Incident. As Robbie recounts, he and his uncle Jorge were on a fishing trip, sleeping on the bed of his pickup truck for three days. They stumbled upon the kindred spirit Captain Louie, who let them sleep in his RV. Three days turned into a weeklong excursion, and on one particular night, Robbie remembers Captain Louie convincing his uncle, who didn’t smoke weed regularly, to have a joint with them. Captain Louie and Jorge got high and were in great spirits recounting old stories about Rene, transcendent fables that were cinematic in scope and danger. “That’s when I knew it was a movie,” he said. Afterwards, Robbie did some digging on the internet, dove into some rabbit holes, and unearthed some leads.

In 2014, at a Miami Dade College screenwriting class, Robbie met Cuban born Pedro Gomez. They went for beers after class and Robbie showed Pedro footage of Rene. Pedro was immediately enthralled by the story, and the pair started hitting up the Wolfson Archives to find old media on South Beach history and fishing.

Back on the beach, I question Robbie on the likelihood of us nailing the big game, and how the beach here compared to others. “On a normal beach, there’s a trough,” Robbie says, which is a long, narrow dip in the shoreline. Miami Beach doesn’t have one. “This is all fake beach. The beach actually starts over there where the sand is. We buried a coral reef here in Miami Beach. Well, the municipal government of Miami Beach did without anyone’s permission. The reef is right here, underneath the ground.” He points down to our toes, half hidden in the sand.

They bring out the kayak. Someone gets in and paddles out to drop the bait. In the distance, there’s a battleship. It’s a dystopic omen on the horizon of an otherwise beautiful day at the beach. Robbie tells me it’s for Memorial Day. The kayaker returns unable to drop the bait. Seaweed Jr goes next. He paddles out past the wave break, seemingly towards the giant battleship on a kayak, as Dante and the Spartans play in the Shallow. Such is the tedious process of shark fishing.

III. Legacy of the Mentor

Eventually, Jimbo started to mentor him, like he did with Rene. If he hadn’t, as he says in an interview on screen documentary, it would have been easy for him to gravitate to a life of crime. This was the era of Cocaine Cowboys and gang activity in South Florida. Seaweed Jr. explains how the South Beach Posse became a persistent presence in the neighborhood. A newscaster in archival footage describes this era of South Florida as a teenage war zone. The version of the man Seaweed Jr. describes that he could have been is a far cry for the man he is today, an admirable father, and coach, a mentor.

In 2003, Rene and Jimbo went fishing in Key West. Rene had a minor stroke and was taken to the hospital. Rene asked Jimbo to take him out of the hospital against the doctor’s request. Rene and Jimbo went back to the Seven Mile Bridge. He caught a shark. Rene died a few days later. Such is the legend.

South Beach Shark Club tells us Rene De Dios is unmatched in shark fishing excellence, this irrational, wearisome, glory filled sport. Unlike Rene, who wanted to be the best, Jimbo wanted to fish. He wanted others to fish. I watch a turtle swim next to him as he paddles to drop bait.

The filmmakers reminded us that legends depend on legacy. It’s why the South Beach Pier Rats moved to bridges after the pier was demolished. It’s why when the shark fishers come out these days, they catch to release. Legacies adapt to persist through change.

Tuesday, May 7th, 8:00PM:

“So basically…. When I hook big sharks, these kids, my football team… I’ll put in low gear and the skinniest eighty pound kid could reel in a thousand pound shark with no problem.” Seaweed Jr. explains. This is because he uses a rod from the 70’s, a technological marvel that comes with two gears and sounds like a car engine due to its complex mechanics.

Robbie and Shannon share stories about growing up on South Beach, about hanging out by the Marina, about…

Click. Click. Click.

Something! Is it a shark? There's a palpable excitement coursing through everyone. Seaweed Jr. thinks it’s definitely a shark. “I’m calling a small hammer,” he says. Because of the low gear, Seaweed lets all the kids take turns at reeling it in.

It wasn’t a hammerhead, as Shannon thought. It was a small blacktip shark. He came ashore with black marbled eyes, a hook in his mouth, wiggling around and fighting like hell. We all move back while the sharkers try to get a hold of him. “Yo!” Seaweed calls out to me. “You got your camera?” He gathers his football team to flank him as he holds down the black tip, still writhing in the sand. I snap the photo. “Move back!” The kids scatter as Seaweed Jr. drags the shark into the water with him, past the current, releasing him back into the sea.

A perfect catch and release.

“Those kids are going to feel so fucking cool tomorrow in school. Like, yeah, I saw a guy catch a shark last night!” Robbie says. He’s right. Everyone there that night has a story to tell.

What is your ideal office?

Any space filled with natural light and positive people.

What is the greatest object you own?

My passport.

Do you have any rituals?

I drink English Breakfast tea and a matcha latte every single morning.

Is there a superstition that your family passes down through generations?

Superstitions passed down from my family all contain items that I have in my home. A cross at my entry, an evil eye on the wall, my grandmother's rosary kept in my bedroom (which I wore around my neck when I had my daughter).

What’s the last thing in your search bar?

Searching for vintage furniture.

Do you have a lucky number?

I gravitate toward anything with a "5" in it.

If you could have a dinner party with three people, dead or alive, who would they be?

Princess Diana, Martha Stewart, Dolly Parton.

What is the ideal setting for stargazing?

Being by the sea and staring up at a beautiful night sky. Grand Cayman has particularly stunning nights to stargaze.

What role does art play in your life?

Art is a huge part of my life with work and personally. I studied contemporary art and it has played a big role in creating interiors, working with artists for residencies and also something in general I enjoy for my personal spaces.

What’s something you hope to learn in the next year?

I want to learn to speak Italian this year. It has been a dream my entire life.

Now in their late 60s, my parents are still writing, navigating an increasingly unrecognizable media landscape. The remaining magazines they freelance for have smaller budgets, and book advances are typically a fraction of what they once were, making it harder to eke out a living as a full-time writer.

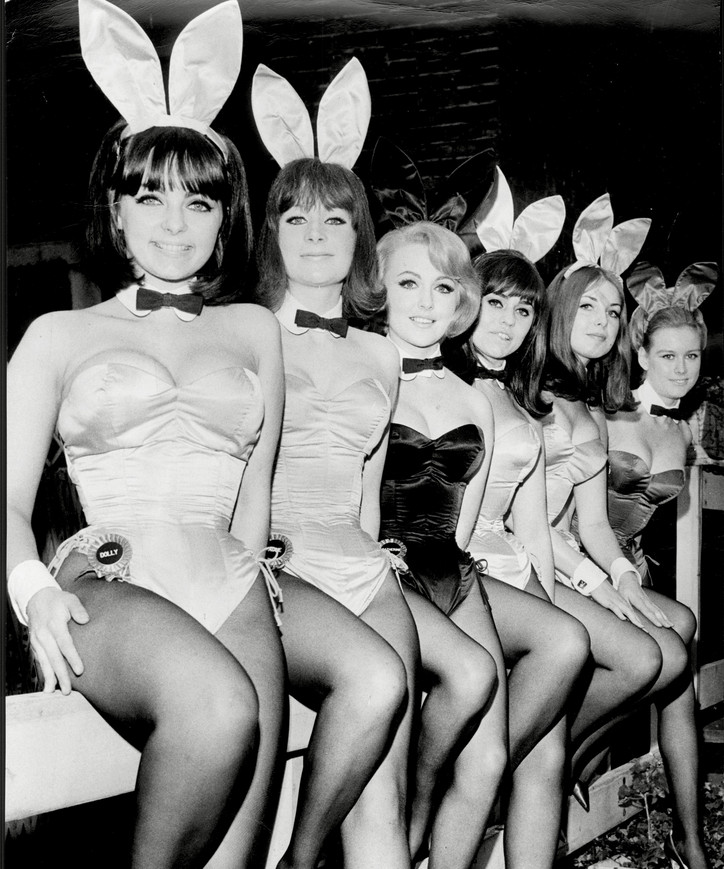

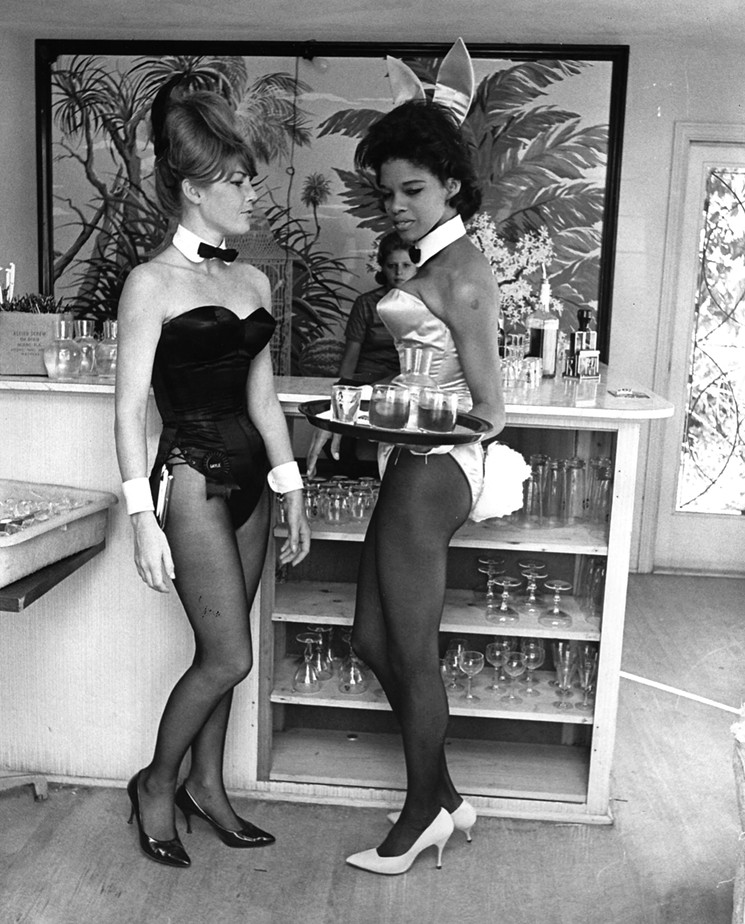

While Playboy remains an influential brand, its business model has changed too: in 2020, new CEO Ben Kohn announced that like so many other publications, the magazine would be shuttering its print editions and move entirely online. That same year, it became a public company, trading on the NASDAQ exchange as “PLBY.”

From its inception in 1953, Hugh Hefner steered Playboy into a brand that represented many different things to different people. Some saw it as a roadmap towards an aspirational lifestyle; to others it was an emblem of free speech and expression; to still others it represented all that was wrong with modern heterosexual culture and was a symbol of the exploitation of women under patriarchy.

However people felt about Playboy, its journalism was always central to its cultural relevance: where else could you get an in-depth interview with Martin Luther King Jr. (1965) or Palestinian political leader Yasser Arafat (1988) and read fiction by Joyce Carol Oates (1970), all alongside centerfolds starring the likes of Marilyn Monroe (1953), Anna Nicole Smith (1992), and Dita Von Teese (2002)?

To see a publication with such an extensive history shutter its print magazine in 2020 felt like a real loss.

Since then, I’d been mulling over a new angle for Playboy. Is there a way to revive the magazine and be financially soluble? Can the magazine retain its core tenets while expanding inclusion along the axes of race and gender? I had some ideas for a path forward, so I set up a meeting earlier this year with Playboy CEO Ben Kohn, who I had been indirectly introduced to (more on that here).

Before our meeting, I had poured over all of Playboy’s publicly available financial records and had a working idea of where the company stood. At the restaurant in Brentwood, Kohn ordered a stack of pancakes and spent the hour regurgitating one liners I had heard him say in countless interviews. (“The brand is popular among the Gen Z crowd…”) But I knew that Playboy was in debt and that its stock was down. From personal experience, I knew that Gen Z didn’t really register the brand as "cool," and that the cheap clothes they license with PacSun weren’t anything I’d ever wear.

Ben — who has a background in private equity — didn’t seem to share in my enthusiasm about the value of resuscitating the magazine. Instead, he talked about the digital platform Playboy Club, which is comparable to a thoroughly unexceptional version of OnlyFans.

In the past, Kohn has stated that Playboy is “the one platform that has a true brand that stands behind it.” But the brand was built on journalism. Once you sacrifice that, what’s left?

‘I read Playboy for the articles’ was a common refrain to justify buying the magazine. The subtext is that a person must create an excuse in order to consume pornography. But the double movement of the phrase was always dependent on the veracity of the claim that one could reasonably read Playboy for the articles. Remove the journalism and fast forward to a cultural moment when pornography is more readily available and less taboo, and there’s really nothing special about a Playboy devoid of journalism.

Nothing came out of my meeting with Kohn, so I decided to stop pursuing the old Playboy and to write about it instead. I started at the very beginning, by calling my mother. I asked if she could send me some photos from her Playboy days, and maybe a few quotes about what her and my Dad think of the fate of the company.

My plan for the article at the time was simple: a couple paragraphs up top introducing my parents’ former roles at Playboy for context, launch into a discussion of the company at present, wrap up with a call to arms about saving journalism, etc. Over and out in a tight 2500 words. Almost immediately, I sensed hesitation. “Is office a real magazine, or is it online?” my mom asked.

Her next question regarded the scope of my article. Would it reference my prior work as an escort? If so, she had a “hard line” about being involved. Given that I hadn’t started writing yet, I responded that I couldn’t guarantee what would be covered, but that escorting didn’t seem directly relevant to the piece and that it likely wouldn’t be discussed.

That didn’t seem to assuage her concern. The next day, I woke up to an email in which my parents declined to give a comment for the article. Their explicit reasoning was a preference for digital privacy in the age of social media. Implicitly, however, was the implication that print media is somehow more reputable than online publications, and that public association with ‘sex work’ made them uncomfortable.

I am so grateful to have two parents who love me deeply, and their approval means so much to me; I couldn’t help feeling this as rejection of me as both a writer and a person. It felt ironic that a part of my life regarding sexuality and labor was off-limits as a condition for their involvement, since I was ostensibly writing an article whose subject was their own former workplace at a men’s lifestyle magazine known for its centerfolds of nude and semi-nude models. Furthermore, the distinction between print and online media privacy felt arbitrary: my mother wrote a memoir about her life in 2005 (the year after Facebook debuted) in which I — as a toddler — am discussed. Why is digital space perceived as more exposed, when similar disclosures of personal information happen across both mediums?

Ultimately, Playboy’s failure to make an effective transition from print to digital journalism doesn’t indicate that good reporting doesn’t happen in online spaces. It just means that writers have to work harder to find them, to make them themselves, and to sometimes waste their time at meetings with corporate CEOs just to ultimately arrive at publication of their work elsewhere.

I believe in the transformative power of good writing. I believe in free sexual expression. For better or for worse, this is the state of Playboy in 2024, the state of journalism, and the state of my family.

Will it always be this way?

"a child of Playboy"

photos courtesy of the author