The Labyrinth is Alive

Tell me about how the project came about.

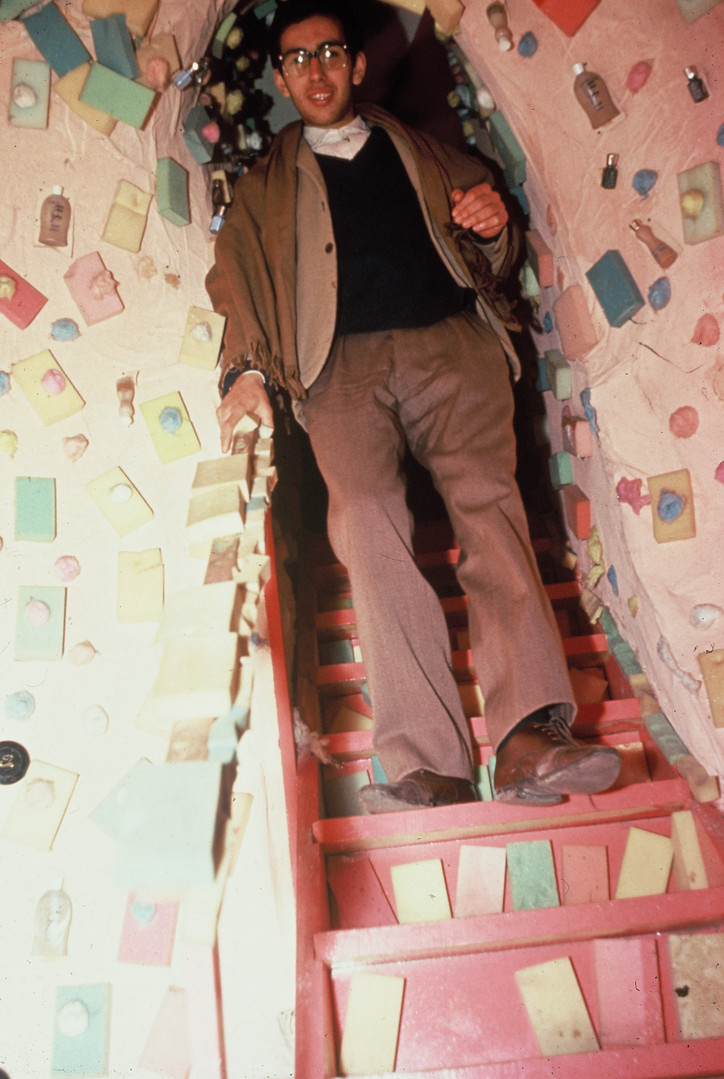

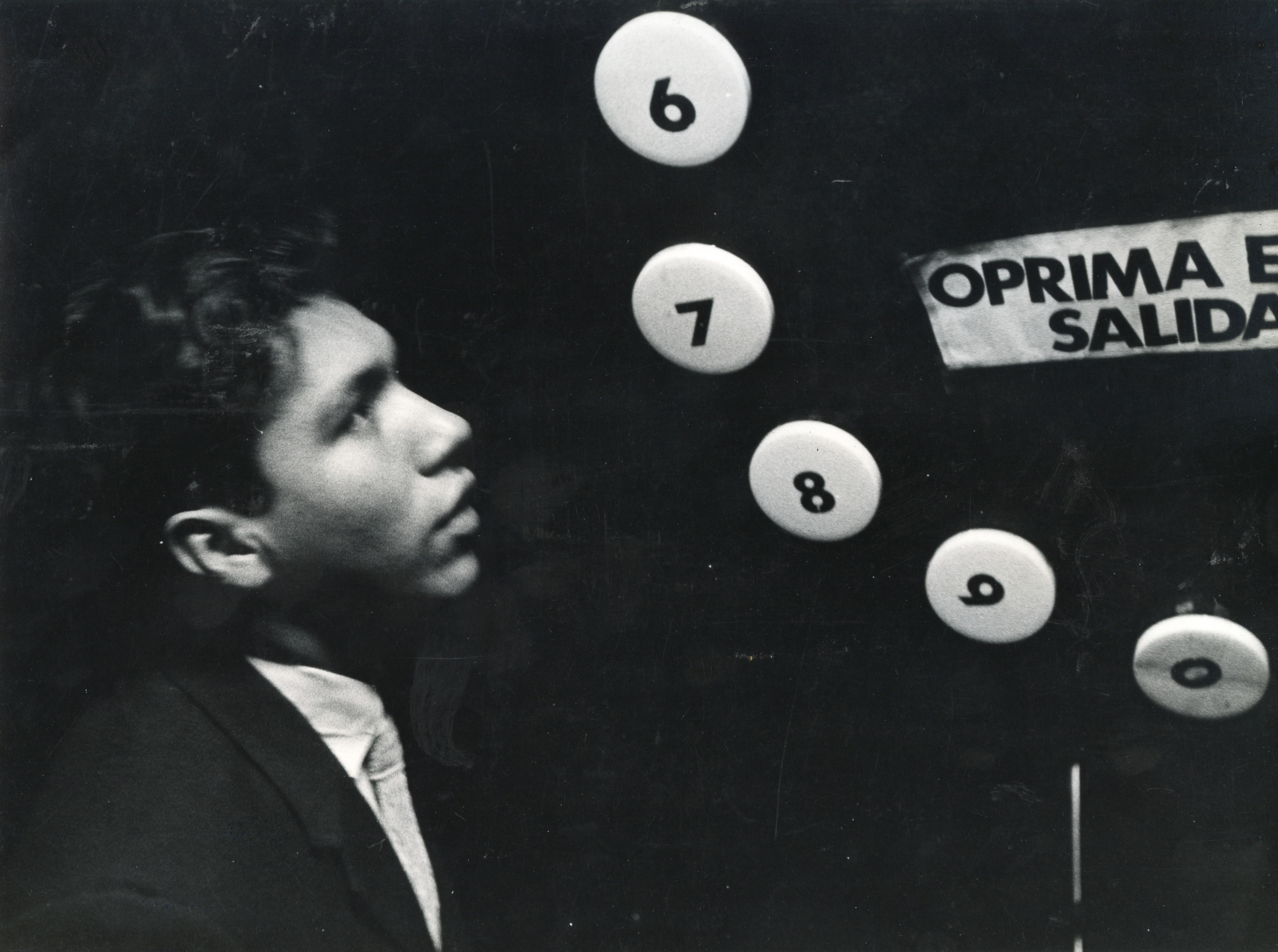

The idea, you see, in the beginning, in 1965 — it started in the 60s, I started art in school and then I dropped out, then went to Paris where I was working with real mattresses from hospitals. And then I started doing like this work, that’s like an environment. What interested me was that people participate in the art, people that live art. So I created in 1963 a piece called The Love Room, that the people had to go inside and had a bed. Then I did another one, because I lived in a big place without bathroom with nothing, and so I thought of a big house with mattresses. Already I was interested in making people enter the piece of art. When I came back to Argentina after spending 3 or 4 years in Paris, a friend of mine was working on something similar that wasn’t necessarily a sculpture. So we were given a big space and we wanted to represent the city of Buenos Aires, that’s why you have the neon representing the movies, the telephone booth was an important element as well — back then we had phone booths. Everything was inspired by the city of Buenos Aires. What I wanted to do was represent the big city.

Is Buenos Aires kind of like a labyrinth?

Not really, no, but I love to make people participate, that they have to select something — they have to think, what do I do, go to the left or go to the right? Because this makes people grow. You are surprised by something that’s around you, and you react.

It is kind of like a little city, in a way, because when you wander through a city you get a little lost.

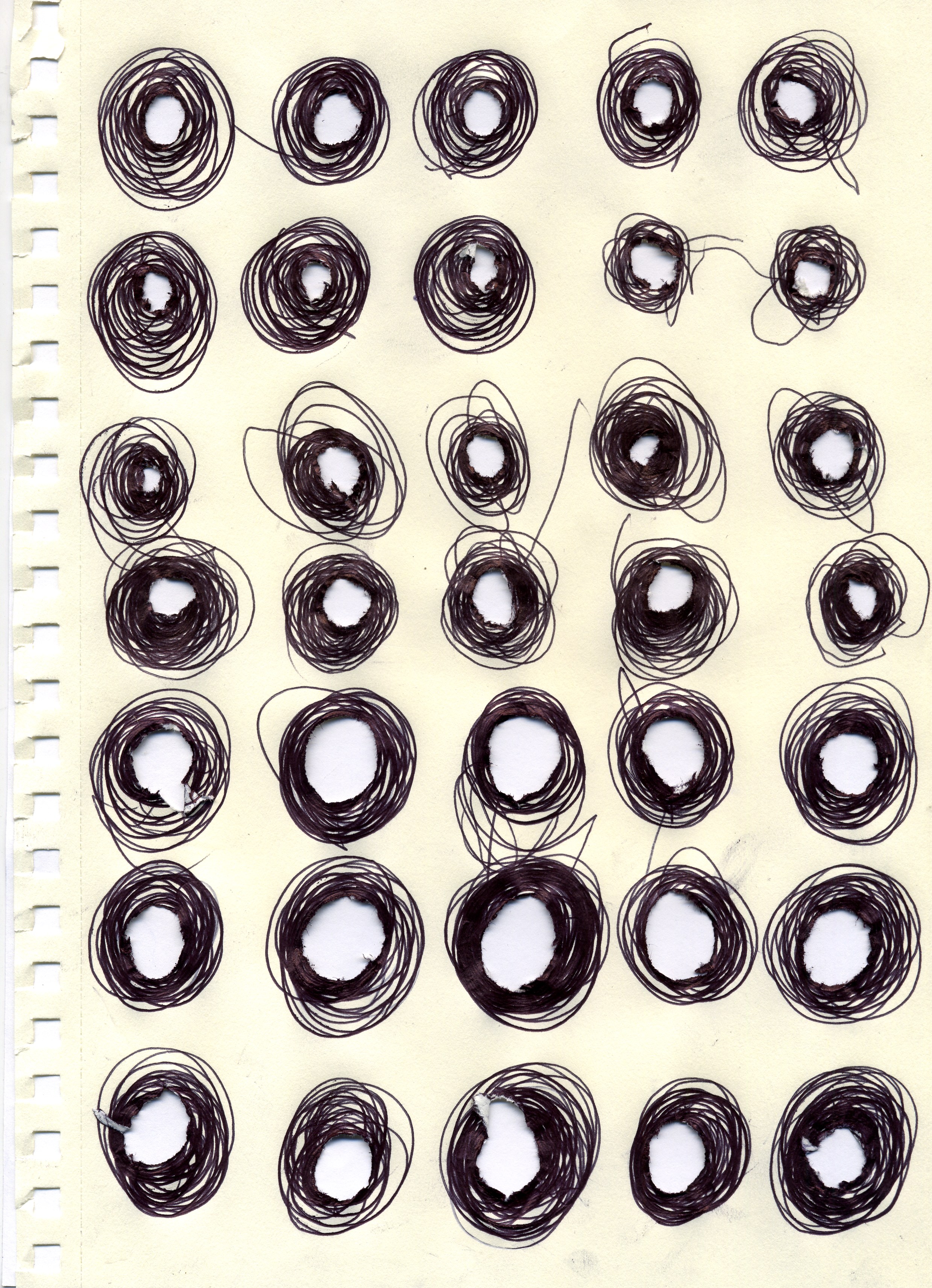

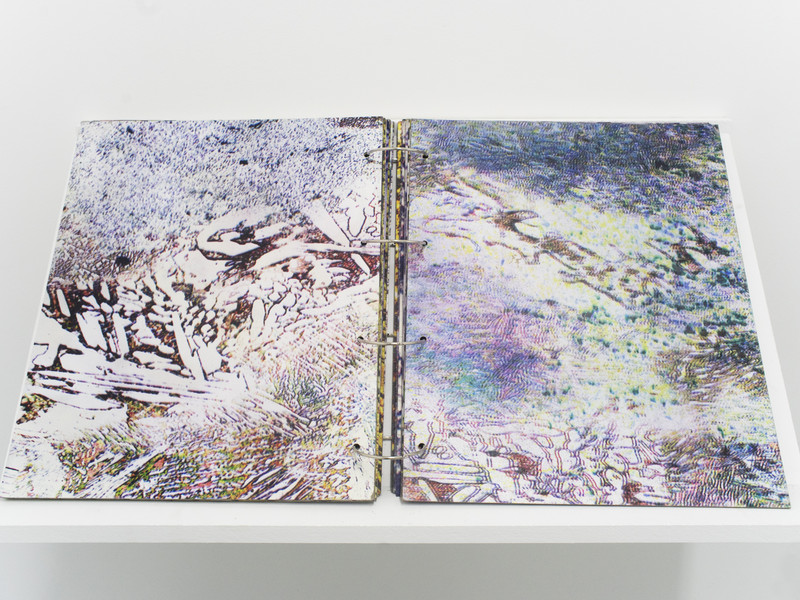

In the beginning in Argentina, the show only lasted 15 days. They closed it and said that we were crazy, but then it was so successful that people who didn’t even know about art would line up for hours just to go in. That’s why in all my work I think about the spectator. When I did the books in the Parthenon (?), it took me three years to collect the books, and then in three days people took all the books. So that’s the idea, to make people work in the art. Everybody is a creator, everybody is an artist. The most creative thing is language, because people talk without thinking. This is the whole idea of what I do — I make a work of art and people react, and they finish my work.

You said that language is the most expressive?

It’s the most creative, because it’s immediate, you don’t have to think about it. It’s the way people express themselves most of the time. When something happens to you, a car accident or something, you don’t know how you’re going to react. So that’s what I’m looking for.

Installations like this remind me of childhood, like a playground or being kind of small.

It’s crazy because originally we had to admit only one person at a time, but now we’re able to admit a lot more.

Do you think a lot of this was happening in the 60s, this kind of artwork?

I believe the 60s was the richest decade in the 20th century, there was conceptual art, pop art, revolutionary movies, the mini skirt, the music — it was such a creative decade. I was twenty years old in the 60s, the energy was just so creative, it changed art history.

Yeah I loved the part where you go through someone’s bedroom, it was so clear that it was the 60s. Do you use performers a lot? I thought that was a really interesting aspect.

Yes. I always use performers — as much as I can. Really, though, the performers are the public. I’ll do a work of art and the public becomes the performers, that is the whole idea.

I actually left without seeing the whole thing because there was a different path that I didn’t take.Is that intentional?

Yes, I love getting lost. There was actually a piece I did in 1995 that was much larger, and people went crazy. It was an actual labyrinth. It was in Buenos Aires for three weeks and then disassembled.

I love the idea of a labyrinth. Have you ever been inside a real labyrinth? Does that even exist?

No, I haven’t, but I like it. I like the idea that people have to choose one way. I love to invent a labyrinth, but I’ve never been to a labyrinth.

Do you have any good stories of being lost?

When I was a young girl, I lived in the mountains in the south of Argentina. I loved the mountains and the forest. I would take a horse and the horse would go his own way and I didn’t know how to get back because there were so many trees and I would get lost.

Were you scared?

Yeah. I didn’t like it.

Do you think that you’re influenced by that?

Maybe. All my life I’ve been inspired by nature, the mountains inspire me, the forest inspires me, the snow. That’s why there’s a refrigerator inside the piece—suddenly you get cold and you are trapped inside a refrigerator, you have all kinds of sensations.

'Marta Minujín: Menesunda Reloaded' is on view through September 29th, 2019 at The New Musuem. Images, all from 1965, are courtesy of the museum.