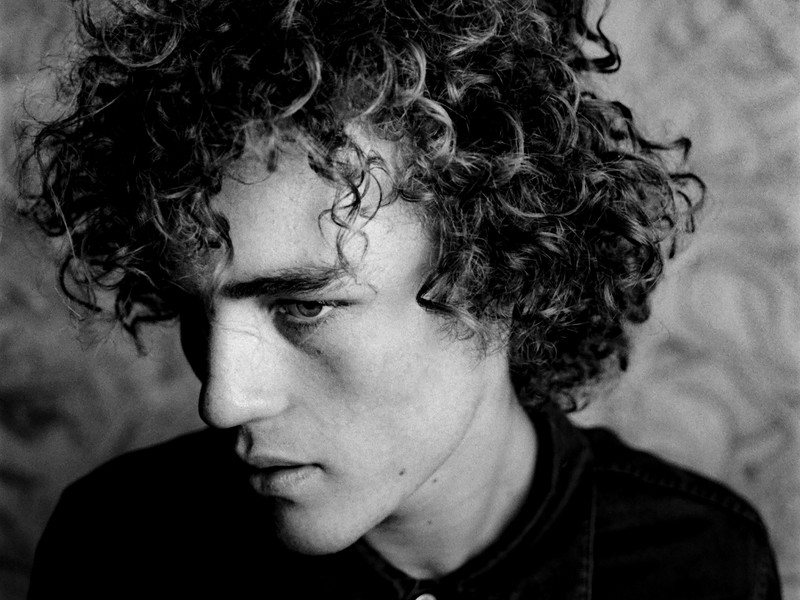

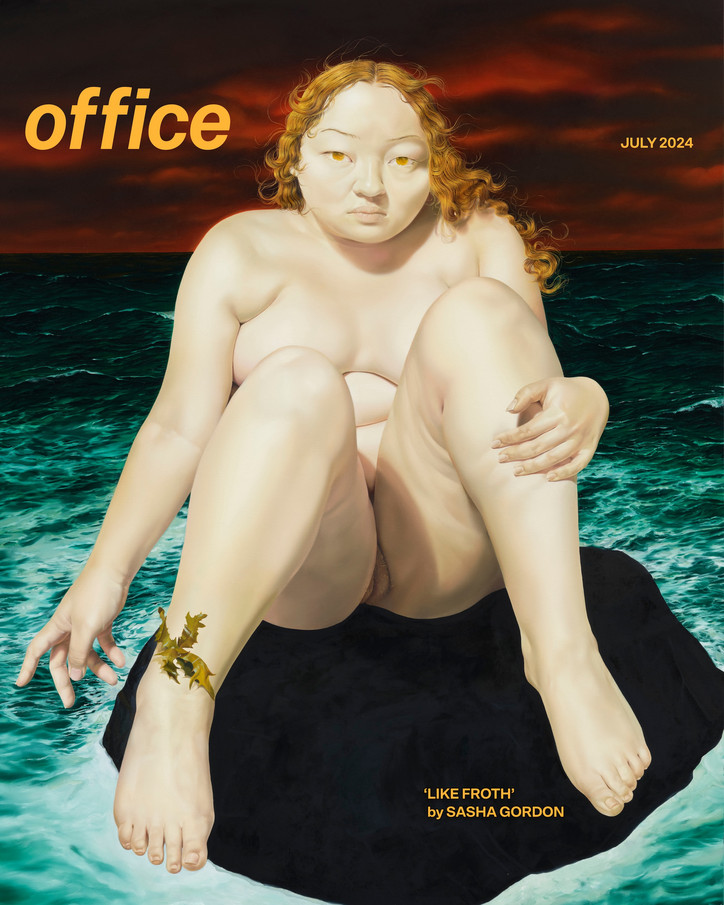

Living in the Limitless: Sasha Gordon

Her debut solo museum exhibition “Surrogate Selves” opened last December at the ICA Miami, merely the latest in a string of solo and group exhibitions she has participated in since graduating from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2020. Few other artists of her generation have managed to achieve what Gordon has, much less so quickly. “People really relate to the paintings,” Gordon says of her success, looking a little dumbfounded. “And, honestly, it's kind of bizarre to me.”

Raised in Somers, New York by a Korean mother and Jewish Polish-American father, Gordon often felt like she didn’t belong in the community around her. “I felt very isolated,” she describes. Finding solace in a series of creative pursuits from crocheting to sewing to fashion design, Gordon would eventually find herself driven by what she calls a “subconscious curiosity” about the medium of paint. By the time she entered high school, she had started to develop a level of technical skill and precision far beyond her years. As she honed her craft at RISD, her works began to catch the eyes of professors and collectors.

Gordon’s singularity lies in the visual language she has been able to develop for herself. In an age where we are all subject to a constant and overwhelming barrage of imagery, Gordon has been able to stand out from the noise. Whether one is familiar with Sasha Gordon's work or not, one can recognize the common language between her paintings the same way one can hear a foreign language and recognize it without speaking it. According to Gordon, she developed that language for herself as she left her hometown and grew into her own independence and selfhood. “I think I was really basing my paintings on how much skill I had,” she says of her earlier work. “In the past few years, I used the skills to translate storytelling and narrative and feeling. I had some great professors [at RISD], and a lot of them were telling me to be looser. I’m a very uptight detailed person and I still am. There’s a way of keeping that but still inventing something new, rather than painting something as realistically or as close to the reference image as possible. There's so much you can do with paint. It’s limitless.”

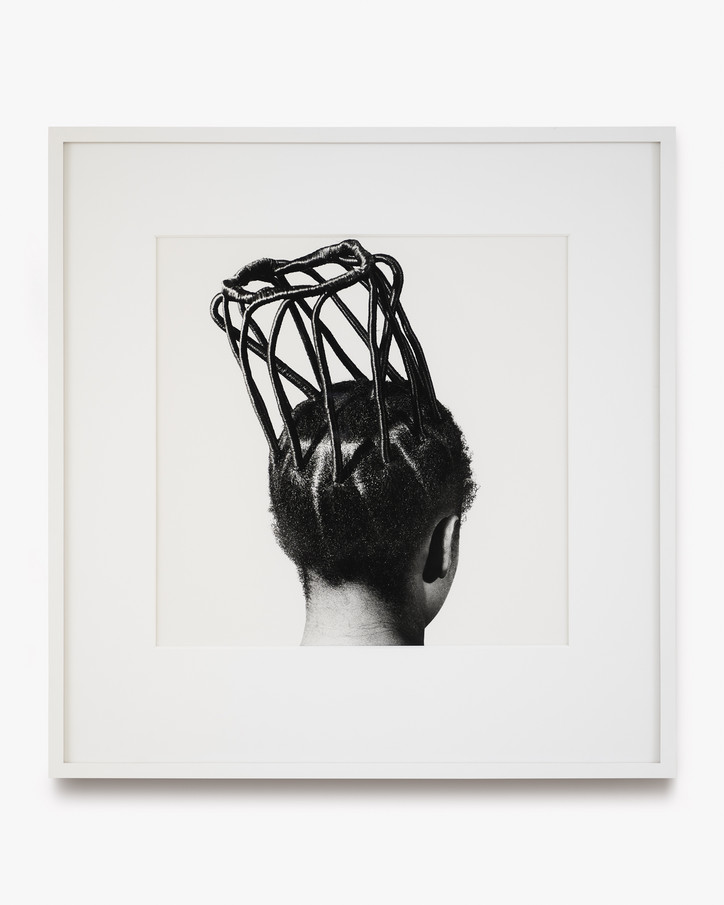

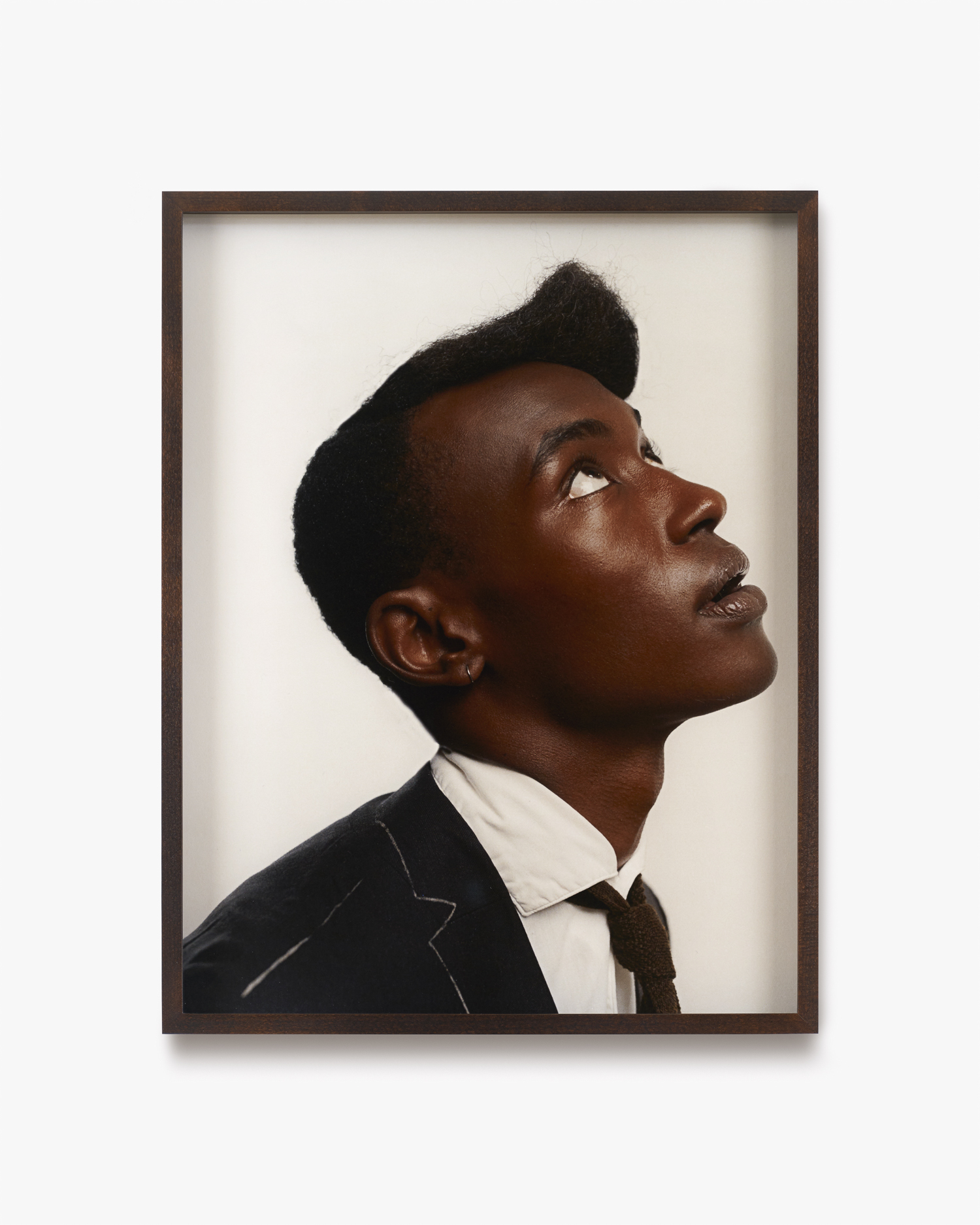

'Something We Said', 2024 'Untitled', 2024

But more compellingly than their technical perfection, Gordon’s paintings are able to evoke the inarticulable and constant discomforts of daily life, emotion, and interaction. “The work is really earnest,” she says, “and that’s because I put whatever I'm thinking out there. I can’t think too much about who’s viewing it.” The effect of her paintings is inextricable from the sense that one gets that Gordon is still painting as though she is alone in her room in Somers, New York. Now that she has had some distance from her childhood, Gordon says she is able to enjoy the scenic nature of her hometown when she visits. “It definitely makes me appreciate my life now a lot more, just because of how alienated I felt growing up,” Gordon says. “I really value my community here [in New York City], and my artist friends.”

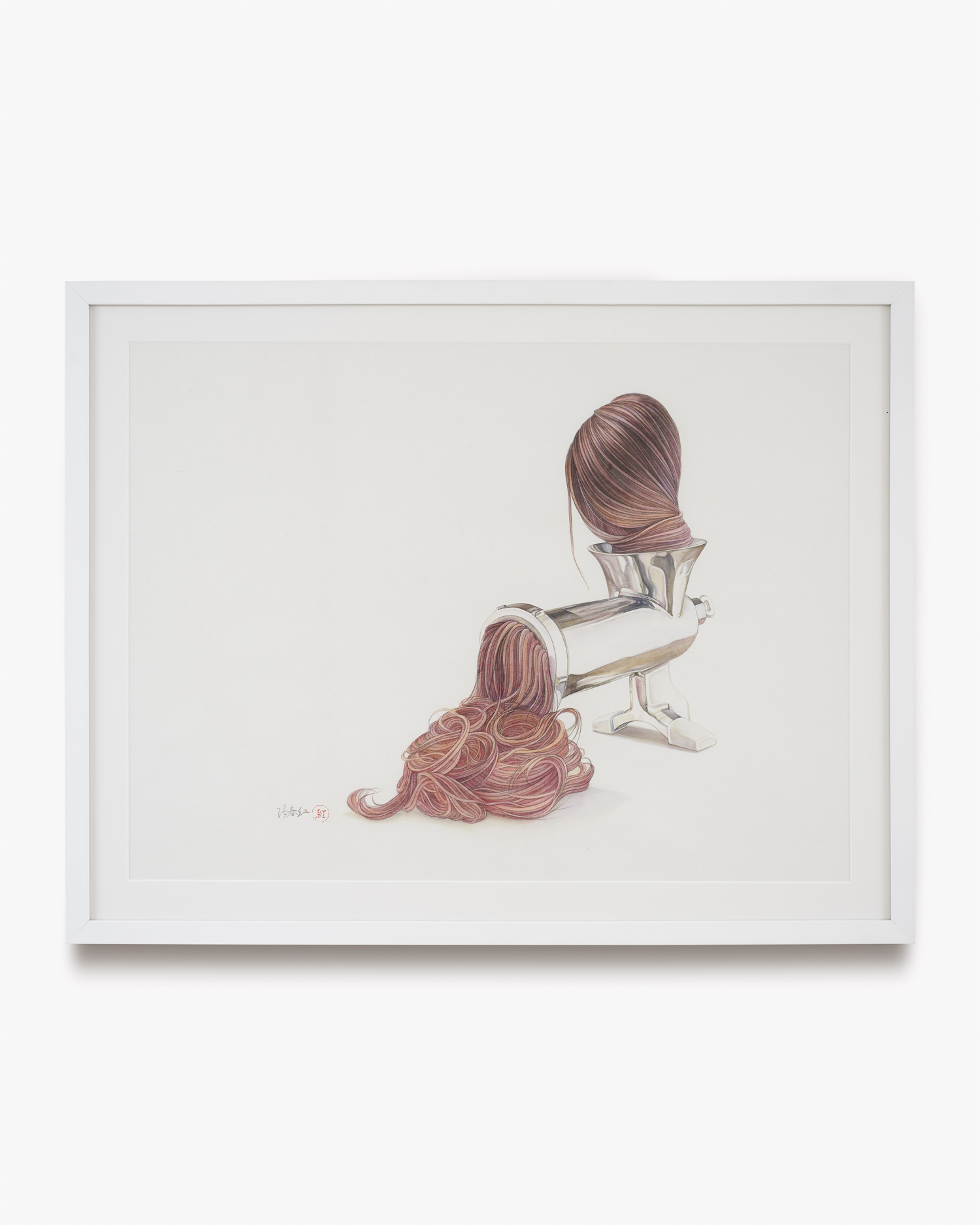

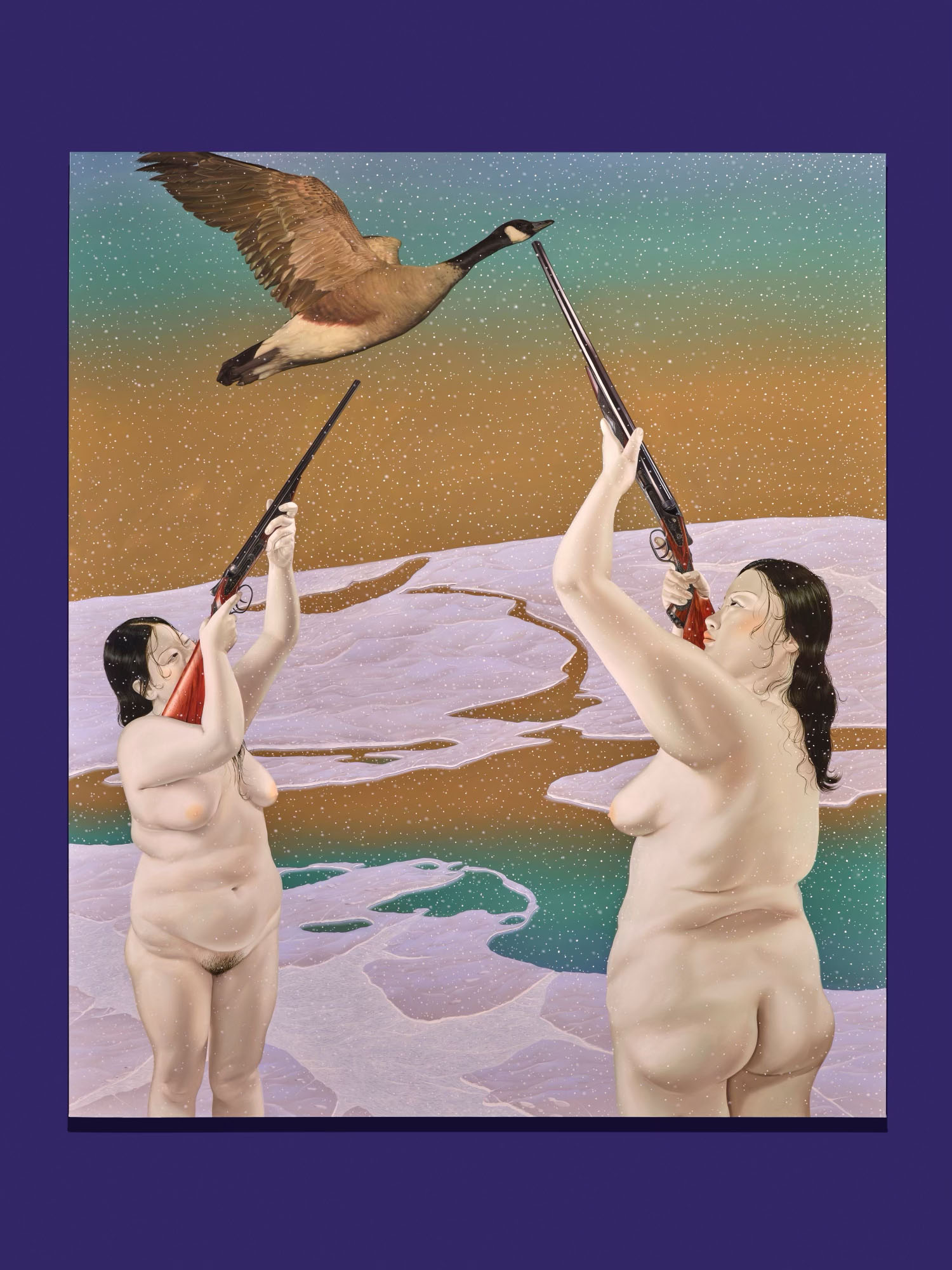

One such artist friend is fellow painter Amanda Ba (b.1998). Both born on the cusp of generation Z and part of what Ba refers to as a “small network” of Asian American figurative painters in New York, Gordon and Ba became close in the last few years but have known of one another through social media for much longer. Ba’s studio is in the same building as Gordon’s, and the proximity of their workspaces allows for hang-outs and informal studio visits with a rare level of frequency.

When Ba walks into the room, she immediately takes note of the plant cutting on the coffee table. “The Pothos grew!” she says, settling into a chair across from Gordon. For the next hour, the two painters trade nuggets of wisdom as they pass yellow American Spirits and a bowl of strawberries between them. We discuss the machinations of the art industry, the influence of their hometowns on their art practices, outsmarting identity politics, and so much more. Read our conversation with Sasha Gordon and Amanda Ba below.

How did you two meet? Did you encounter one another’s work before meeting?

Sasha Gordon— I found you [on Instagram] around the end of high school. One of my old friends showed me Amanda’s work, like “Oh, I think you’d like this girl’s art.”

Amanda Ba— I definitely saw your work online before I ever met you in real life.

SG— In high school, I wasn't familiar with any Asian artists, or any artists of color. Then in college, I did my research, and I saw some established artists that dabbled in really similar stuff as me. But seeing someone my age was just really important; we're both coming up in this kind of confusing art industry and world. And I thought she was so talented.

We didn't meet [in real life] until, like, three or four years ago, because we were both in college.

AB— Yeah. And we were always friendly, it was just sort of this distant observation until we met and got closer.

Before showing in a gallery, I didn’t really have a very concrete sense of how things in the art world operate. I painted progressively more as I got more into my major requirements towards the end of college. I think we were both experimenting with a lot of different styles.

SG— Yeah, we don't paint the same way as we did then. Not at all.

AB— No, not at all. But yeah, I mean, it was sick to see someone doing really well, whose work I identify with. And it was good motivation. Not necessarily competitively, but just motivation; you see someone else's work that you really like, and you're like, oh, I wanna do better.

I think that as we grew up, entering the art world, or just becoming more familiar with it, it became more important to actually make note of other artists’ work. When it comes to Asian figurative painters in New York, we probably know most of them either peripherally or we’re friends with them. It's just a small-ish network.

You both had this experience of entering the art world — to use your word, Sasha, the art industry — at quite a young age, and have experienced a rise in visibility for your work rather quickly. But you’re also both still young, and still growing up. Typically the art is thought to reflect life, but how much do you think the forces of the art industry are also influencing your lives? How much does that then show up again in the work?

SG— I don’t think anyone’s ever asked me this before. I feel like [the influence of the art industry] is pretty constant. I'm having at least a few studio visits a month, and talking to other artists, and seeing galleries, and I try to stay up to date with other painters. And then there’s art fairs.

AB— The fairs are the only thing that resembles an office or work environment.

SG— Yeah, it’s really bizarre not having a set schedule. The art fairs do kind of make a replacement for that, the fairs are when you become social. Otherwise, it’s quite an isolated job.

AB— Scheduling in the art world definitely dictates the pacing and the work-life balance of your year. And for example, my show is set up to coincide with the beginning of the art world season in the fall, and art fairs like [the] Armory Show…

SG— Frieze too, there’s a bunch of art fairs. That’s so true.

AB— And they all happen around the same time as fashion week. If anything, actually, the broader world is always on a school schedule. Everything starts in September.

What about its impact on the pace of your production?

SG— I feel like there hasn't been one show where I’ve had extra work, or finished on time. Almost every due date I've had, I've pushed by at least a week or two.

AB— It’s on us to agree to the deadlines; we decide how much of a workload we can manage within a very long time. And it's bizarre to think about a project that could be a year or more away, and how you're going to keep yourself paced during that time. But there’s nothing else dictating our work time.

If we had time to just chill with paintings and experiment with no deadline — I actually have no conception of what that might be like.

SG— Right. It's so weird also, because you never know how long something is going to take. So I feel like you sometimes have to grind just to be safe.

[The pacing] definitely helps me, personally. I think it pushes me to work in a different way than I'm used to, and I learn a lot from that. I can get super obsessive, and if I didn't have a deadline, I could probably work on one painting for eight months.

Now, I've gotten way more accustomed to the schedule of things, and there are some moments to be expected where the end result might not be exactly how I pictured it.

In the last several years, there has been a massive uptick in fascination and interest with “artists of color” and “marginalized” artists, which has also been coupled with a very exploitative model within the art world that can reduce people to just their marginalized identity. How are you thinking about navigating that in your work now?

SG— I remember a professor I had, who is a Black queer painter, and we were talking about this topic. She was saying that she paints Black figures, but she doesn't feel like she needs to explain it or go into such detail about it, because she just exists as that.

That really struck me, because I was doing more work about identity a few years ago, when I was discovering a lot about myself and was reflecting on my whole childhood experience of growing up in a white community. I think it was important for me to make those paintings, I definitely go back to those paintings a lot, and sometimes I find the paintings I'm working on currently have more to do with identity. But I don't feel like I need to talk about it in every interview or every artist talk.

I think the paintings have more to do with the psychological effects of that experience, not so much being Asian or [asserting] that representation is so important.

AB— I love talking about this topic. I think that what your professor is getting at is, why aren't we ever questioning paintings of white people? Why is it not shocking to paint them? It's a given, it’s not a big deal, and therefore it's omnipresent, but it's not the focal point, right? It's just part of the experience, part of a continuum.

SG— If you paint an Asian person, it’s like, “look at this Asian American painter Amanda Ba!” But would you ever say, “look at this white painter?” because someone painted white subjects?

AB— The natural, intuitive motion is to insert people that look like us into the canon. The goal isn't to, like, recognize Asian people. The goal is to have images of people of color be treated as commonplace.

I don't know if we'll ever get to this point, but if there was a more adequate sense of representation, maybe we would then have the freedom to go and, like, become minimalist sculptors or something.

SG— That would be awesome. [Laughs] I mean, it's cool sometimes when I see artists who don't have any take on identity, and just make beautiful images. That must be nice, to not have these ideas assumed and placed on the work in the way that it happens to us.

AB— It's also about how much responsibility you feel and want to take on, and then want to project out into the world. We totally have every right and reason to say fuck all, and make work that’s maybe even devoid of figures. But I think it's also about complicating identity to a point where it's less easy to explain. You can't just indulge yourself in your own intentions or whatever; you have to be aware of what is always out there.

So how do I outsmart that in some way? Can I make the painting so complicated that they have to think about something else?

You both grew up in places that were not major cities or considered hubs for art, and I’m curious how you think that affected the development of your practice. Had you grown up in New York City, do you think your practice would be different?

AB— I have no idea what it would be like to grow up as a teen in New York. That really perplexes me.

SG— I heard there's almost too much freedom. I can't imagine. I was so sheltered and had very limited resources compared to what I have now living here. I feel like… maybe I wouldn’t have painted?

AB— You might have just been having fun, partying.

SG— I also think being sheltered definitely made me. I had to learn a lot on my own. I didn't have access to what I wanted, which was more of an art scene. So I kind of had to do my own research by myself, and really spend a lot of time practicing the craft and building up that level of skill.

And if I didn't have that transition, from growing up upstate to moving to Rhode Island and then the city, I don't know if I would have come to all these solutions and conclusions of my experiences and my identity. Making this more narrative work — I don't know if that would have happened.

Do you ever have informal critiques with each other?

AB— Every time we see each other is a little bit of an informal crit.

SG— Sometimes I need a second opinion. I don't always take the advice, but I like to hear it. I definitely value what Amanda thinks of my work, so I want to hear her take on things.

AB— Yeah, same. I feel like sometimes I come to you and just ask, like, “what color?”

SG— We'll show each other like artists we like. We're constantly looking at Lisa Yuskavage’s work together — you can tell when we were starting a painting, and we pulled up Lisa’s website.

AB— Painting, at least the way we paint, is harder to critique and then go back in and change something drastic. But we are catching each other at stages where there’s actually a decision tree, a fork in the road: this way or that way.

SG— In college, critiques were our main way to get to talk about the work and run ideas through people. It was an adjustment to move to the city during COVID and not have anyone see my work or get to talk about it. And it's nice to have studio visits, to be in the same building with Amanda — we call it school, it almost feels like camp or something.

AB— We hang out as friends, but if we're hanging out in our studios, the work is always peripheral. You know, I think your studio is the only other studio I see so consistently, like multiple times a week, steps and steps of progress, talking to each other about color palettes, and compositions.

SG— Yeah, it's really nice. We can visit each other and it makes us realize there's like a bigger world out there than just our studios.

AB— Friendly competition is so helpful to me, too. It's just like, wow, this person made something amazing, and I want to make something better. The speed of the art world makes you feel this way, but it's not this limited set of ranked spots. The goal should be to expand. When I see someone make a really great painting, I'm like, fuck, I wanna go back and make a really great painting.

SG— I remember we were talking once about some artist, and we were both, like, almost jealous of them. We were really critical of their work, but I think it's because we were so moved by their skill and technique. It's so cool to like, keep in touch with all these people, and see what they're up to — to motivate each other with each other.

Sasha, a while ago, you said that you were curious to see what the work would look like if you weren't showing. Have you had a long enough period to actually get to see that? If you did, how do you feel that the work has changed?

SG— I don't think I have. There was the first show I had, I had like a year and a half, and that was actually kind of challenging. It was during COVID, so pretty much no outside opinions, or advice. Recently, it's been like I’ll have a show and then I’ll have 5-7 months ‘til the next, and I don’t really have time to… I think I said I wanted to make “ugly” paintings.

AB— What about this one? I feel like this is the only one. [Points to a painting on the wall]

SG— That’s true, this is the only one I did because I was a month into dating my partner and it was a present. And that was fun! I feel like it's looser and smaller and there's no expectation.

I constantly want to make better work, and I feel like I've set up a certain standard for all my paintings having insane detail and huge scale and new innovative ideas. It has been hard to do, but every now and then I get a chance to try to make something weird. I don't have to show it or display it, I just keep them. I definitely want at some point to have a full year to just make stuff with no goal of showing any of it.

I actually will be going to Italy in October for a residency, so hopefully I can do some more exploration then. I went to Rome once to study abroad, and I also changed a lot during that period. I think being away from the city, and other artists and friends, it just inspires this freedom to fuck around.