Long Live Young World

As it turns out, the independently-run festival banks heavily on Rule #1 of Alvin and the Chipmunks’ lore — when I arrive about twenty minutes prior to its advertised 5 PM start time, I’m met with scattered throngs of teen-aged friend groups sprawled out across household sheets, some heads rested on the outlines of Poland Spring bottles in drawstring bags, and others nestled in the withering grass of Brooklyn’s fabled Herbert Von King Park. In front of me, one kid seated next to an ostensible girlfriend is wearing a graphic T-Shirt, the back of which reads “DELIVER ME FROM THIS MORTAL COIL (Obscure Image) FOR THERE IS NOTHING FOR ME HERE.” It’s a sentiment that must be echoed by the tightly-wound modus operandi often inherent to events of this nature: in place of strict seating arrangements, itineraries and clear-cut direction, there is, instead, free will, a wherever-you-can-find-shade seating policy, and a widely-circulated notes-app setlist that many attendees impatiently consult screenshots of between performances. Deliver rules from this mortal coil (obscure image), for there is nothing for them here.

For most of the twenty or so minutes I spend waiting for the show to start, the kind of music a cultured grandpa might cue up on aux is blasting from jumbo speakers stageward — one track is Gang Starr’s “Moment of Truth,” which features old-head-friendly maxims like “Actions have reactions, don't be quick to judge / You may not know the hardships people don't speak of” — and a lanky, beer-toting middle-aged man in a white Minnesota Vikings jersey is strangely glancing back at me with arched eyebrows. Whatever his problem with me may be, it seems to be alleviated when, after a series of hushed phone calls and photos of his surrounding area, he runs towards a woman in the portion of the park exposed to the heat, and, like something straight out of a coming-of-age film, they embrace in the golden hour sunlight. Everything here is strangely, endearingly cinematic, which — as cliche as it sounds — makes the whole function feel a little bit like a weirdly beautiful, hyper-grassroots Woodstock on a budget. This is, perhaps, part of what allows its collectivity-oriented selling point to work so well: just as much as there’s nothing besides vibe-check-passing security guards separating artist from audience, nothing’s separating the audience from itself either, and by the time the music's over, you realize that for most of the show, you and the five or so strangers in your immediate area have been taking turns fanning each other with the plastic contraptions handed out by park volunteers earlier on. (An exercise, I must stress, is incredibly necessary, at least in my case — today is my first day using an insulated water bottle my mom got me, so it pains me to see that when I open it up, all of the ice I put in it this morning is still ice. For further context: I am wearing a predominantly black rugby shirt and Champion sweatpants, with an extra pair of gym shorts underneath.)

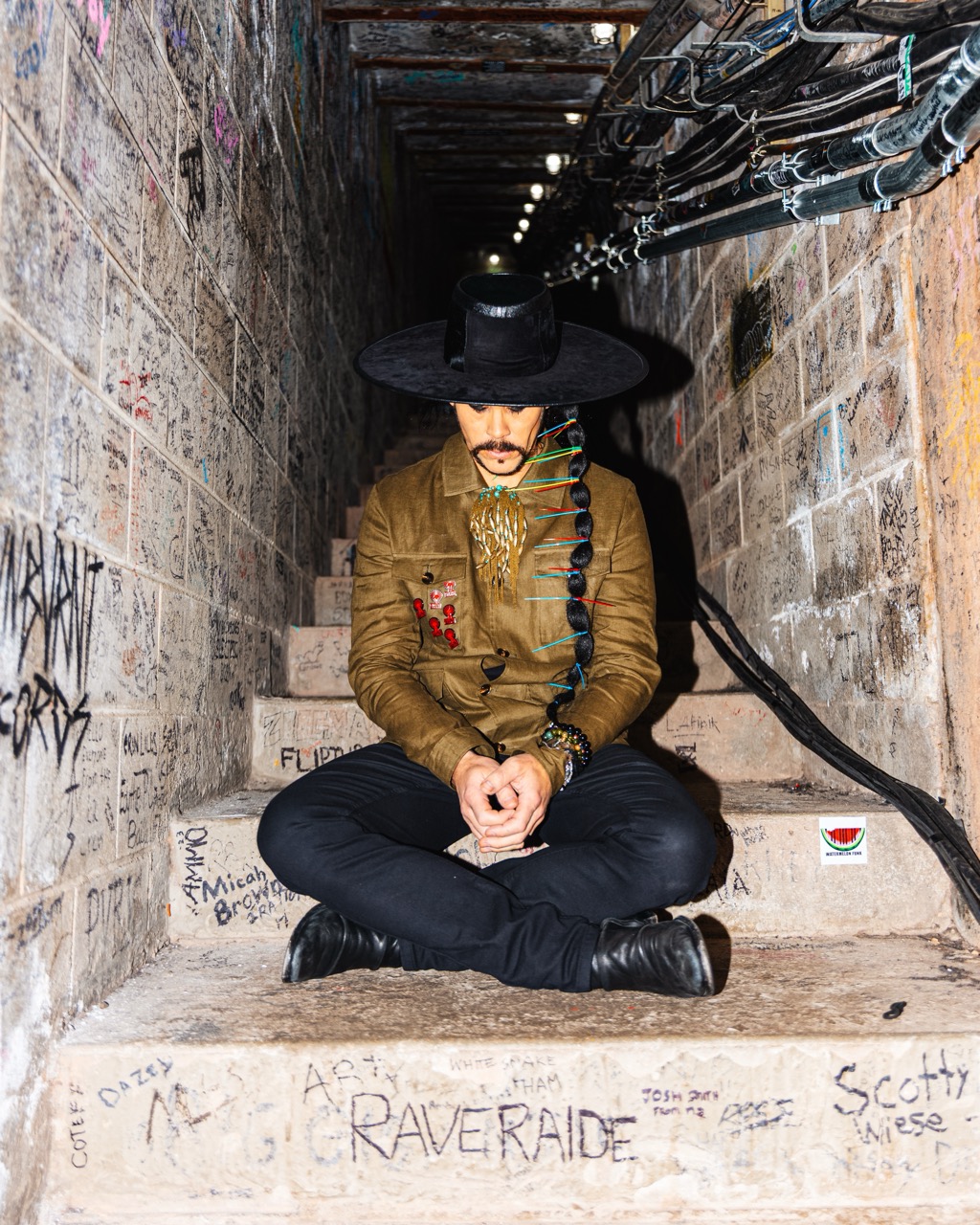

Young World was founded with these kinds of grassroots, community-centric ideas in mind. “I always thought about artists who have the ability to create their own world, and build that from scratch or from nothing,” MIKE told Rolling Stone prior to this year’s installment. “When I think about basically all the artists that are on the bill, it’s people that have created those types of worlds with music and shit, at least to me. [...] I just want people to be allowed to enjoy good shit. You shouldn’t have to pay mad bread for a good experience.” Along with MIKE, tonight’s bill features DJ-slash-producer Laron, gentle-voiced UK spitter Jadasea, avant-garde Brooklyn wordsmith Maassai, the skate-adjacent Soulja Boy-incarnate TisaKorean, the defiant Jamaica-forged MC Junglepussy, and the OG hip-hop storyteller Slick Rick. Among vendor offerings lined up near a set of benches on the park’s side, there’s live screen printing by AINT WET, clothes by RIGHTEOUSPATH2002 and LOVEGAME, and food courtesy of Sol Sips. As crowds of cultured teens and 20-somethings oscillate between the booths and the stage, it’s difficult to distinguish any one reveler, vendor, or friend group from the other. Everyone is at the same level, and MIKE & Company probably wouldn’t have it any other way.

Donning a floppy bucket hat and a gray T-shirt, Laron graces stage a little after 5 PM, at which point — with the help of tonight’s host inviting everyone closer to the stage “so you can all see how pretty I am” — a good portion of the teens laying in the grass by the vendors make a long, smoke-filled pilgrimage to the front of the platform, forming the humble makings of what will soon, over the course of the night, spill out into a massive, undulating swarm. “Young World” applies to everyone here, and this dynamic wastes little time making itself visible. Midway through Laron’s set, an elderly couple drags a pair of green lawn chairs to the front of the head-bopping teenage assemblage, and perches, unbothered, directly behind the barricade. (When they aren’t dancing for the Instagram stories of friendly schoolchildren around them, between sets, they’re pulling out their phones and playing the kinds of Candy Crush spinoffs you see ads for on Twitter.)

It’s a fitting embodiment of the family-oriented approach long prioritized by this corner of New York hip-hop’s underground. The last time I attended something of theirs in-person, it was October, and MIKE was in Nashville for an early stop on his “Small World Big Love” tour. Upon entry, the pair of elderly security guards that checked my ID asked me, with genuine curiosity, who “this group” was. The urge to ask that question was easier to understand once I got inside: in the front row alone, the mixture included smoke-puffing students from local colleges, awkward adults who had traveled solo, and an annoyed-looking father who, between glances at his watch, occasionally reminded his middle school-aged son that “you have to wake up for school tomorrow.” The list of acts (or events, generally speaking) capable of bringing that blend of people into one room, let alone one row, is a short one — and it’s a feat you only achieve when your music can turn fans into family. Both last October and today, the people responsible for this gathering seem to have mastered the formula.

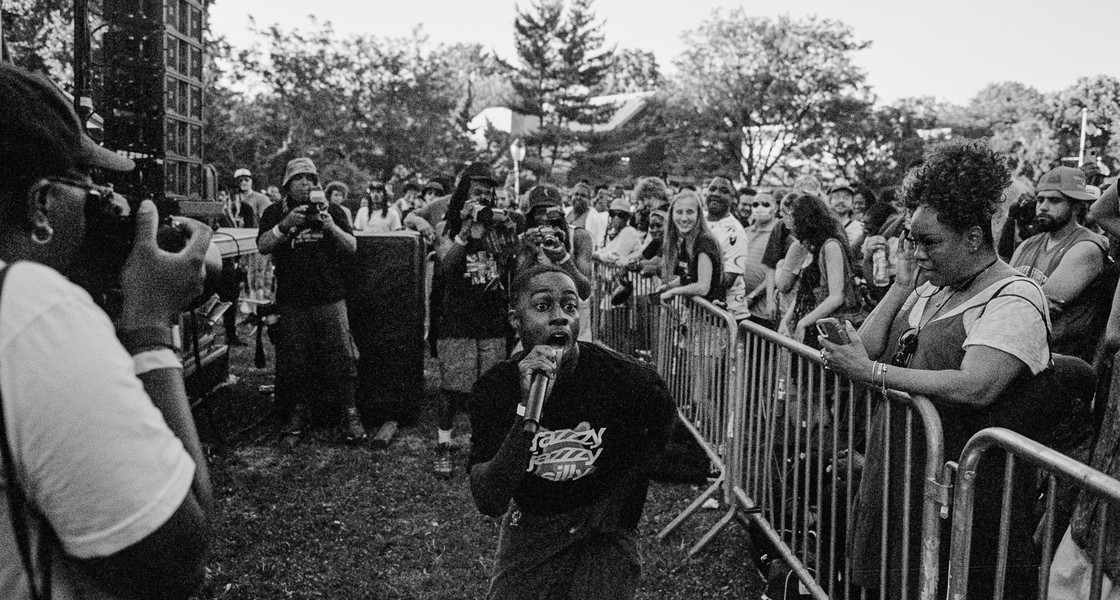

The next performer is summoned via a series of yelped demands from tonight’s host for the audience to shout louder. This doesn’t end up seeming all that necessary, though, because by the time MIKE glides onto the platform alongside his longtime live DJ Taka, the loudest roar of the afternoon has already begun erupting from what is now a significantly larger sea of people on the grass. MIKE’s live act is hinged just as much — if not more so — on highlighting the talent around him, as it is on highlighting the talent he himself has to offer. It feels ritualistic when, in the spoken interludes that carry one song into the next, he breaks into spirited monologues, venturing to thank everyone around him one by one: “My name’s Mike; this is my brother Taka,” he’d start, with rhythmic swagger, pointing a shaky finger back towards the baseball cap-clad mastermind behind him. “Can you guys do me a faaaavvorrrr?” Taka would modulate MIKE’s voice to the point where, with luminous echoes and booming, layered depth, it sounds like that of a disembodied, mythic prophet. “I need y’all to make the most noise for my brother Taka.” The crowd would make the most noise for his brother Taka. “Could you guys do me another faaaavvorrrr? I need y’all to make the most noise for my family in the back.” The crowd would make the most noise for his family in the back. When MIKE raises his arms for the final time, the list of figures he’s thanked includes his manager, every artist on the bill, the vendors, the sound technicians, the lighting technicians (“Come on y’all” he says flatly, when insufficient noise is made for this group. “Can we please get some more noise for the light people.”), and — most often of all — the audience itself. You’re never just applauding MIKE. At the same time that he’s making you love him, he’s making sure you love yourself, and the people around you, too.

After two lyric-heavy masterclasses by Jadasea and Maassai — “I don’t like talking too much, so let’s just get into it,” Maassai fittingly announces, before her sacred, Nas-evocative set begins — TisaKorean greets his raucous crowd with a series of brazen declarations about how “silly” he is, which all serve to operate as both a warning and a trademark. He’s flanked by a dread-headed skateboarder who does kickflips back and forth across stage throughout his performance, a young rapper named Mighty Bay, and an older, cell phone-toting manager-type, who — speaking of “deprecating”— Tisa jokingly instructs to “get the fuck off the stage, man!” The reason for his ousting is an obstruction to the show of some sort, an infraction that seems to be part of a well-oiled skit. “He always do this shit,” Tisa comically groans. “On the count of three, Imma need y’all to yell Fuck you! One. Two. Three.”

“Fuck you!,” Herbert Von King Park collectively shouts, and the man trudges his way off the stage with his head bowed.

TisaKorean’s stage act looks a lot like someone gave a wild-minded fourth grader, midway through about seven different phases, fifteen minutes to answer a narrative writing prompt — If you could have your very own concert, what would it look like? — for extra credit in an English class taught by a progressive old woman who lives in Forest Hills. And, much like that wild-minded fourth grader would imagine, it’s glorious: all between plagued shouts of “Why am I so silly??,” he’s either moonwalking, jumping clean off the stage and within inches of the front row’s bulging eyes, dousing himself with the entire water bottle the aforementioned managerial-type gave him to drink, or demanding that the audience join him in yelling himself hoarse. “Why y’all looking at me like I’m crazy?,” he asks, genuinely perplexed, when he showers himself in Poland Spring. “I just wanted to pour some water on my head.” It’s an endearing microcosm of Tisa’s all-out impetus writ-large: the same way showering himself in water is a natural response to extreme heat, being “silly” is another itch it’s simply in his blood to scratch. If the raucous quasi-moshpit that has formed around me indicates anything, it’s that the “silly” itch is highly contagious… but compared to other contagious things making headlines today, everyone seems beyond content to allow this into their collective bloodstream.

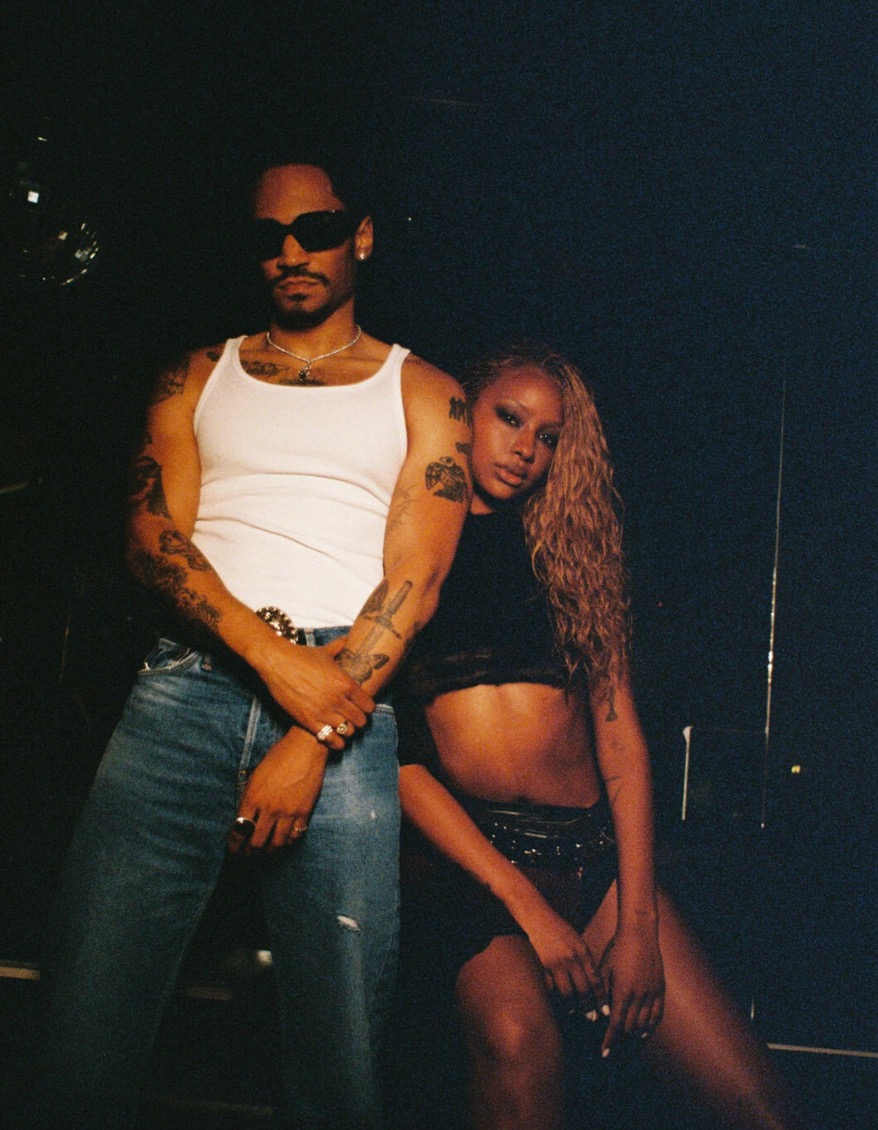

Following a lengthy changeover DJ session by London’s RedLee — it’s necessary to state that, between transitional DJ gigs before and after every act, and the occasional verse during Jadasea’s set, he’s been working overtime today — the next performer to grace the stage is Junglepussy, the Brooklyn MC whose liberating songs of sexual autonomy have fostered a vibrant, militant community of listeners who flock to the music to find empowered versions of themselves. This is perhaps most visibly true when, upon her emergence from backstage, a group of it-girls huddled together in the front let out a shout so crazy that the rapper’s voice, microphone and all, is indiscernible in my already-hazy tape recording. A similar dynamic winds up being the case for most of Jungelpussy’s set, and as the me of the future writes what you are currently reading, he is frantically fast-forwarding and rewinding his audio file from several nights ago, in desperate search of any wise words — of which there were many — spoken by the defiant spitter that he can salvage for inclusion in this overdue article. Below is a list of the perceptible ones he’s able to swipe off of his SD card:

[Spoken to a lame hypothetical ex-boyfriend] “Yo’ big-ass head… Yo’ ashy butt-crack… Who else gon’ twist ya dreads?? I oughta (indiscernible)! You got a nasty attitude… I don’t like the way you treat me. I don’t get horny when you look at me. You wanna know what turns me on? I met this one (indiscernible) motherfucker… (...) his ass took me to the zoo. The zoo? The zoo. Last dude bought me (indiscernible) lingerie, I’m like eewww! I got n***as taking me to see live animals!!”

“You are now in the presence of an empress.”

“I am so honored to be here… shout out to MIKE, shout out to Young World, shout out to my family here in the b- I was boutta say in the building, but we on the lawn like…”

“You think you up next, but bitch, I’m adjacent.”

Junglepussy’s set is one-third PSA, one-third militant ritual, and another third oral essay. Due in part to her performance’s stream-of-consciousness nature, the audience is stirred into a frenzy every time she utters a mantra they can latch onto — an occasion, as you could likely tell from the above transcriptions, that repeats itself often — but, as valiantly as she’s feeding into the crowd’s fanaticism, it’s also somewhat plausible that she’s doing it just as much for herself. When she lurches into her deep, guttural act, it seems like somewhere behind her dark inconspicuous shades and seductive croon, a switch is flipped, and everything inside comes out in an endless deluge, solely interrupted by applause. By the time she’s through, the spell, much like Tisa’s, looks to be infectious.

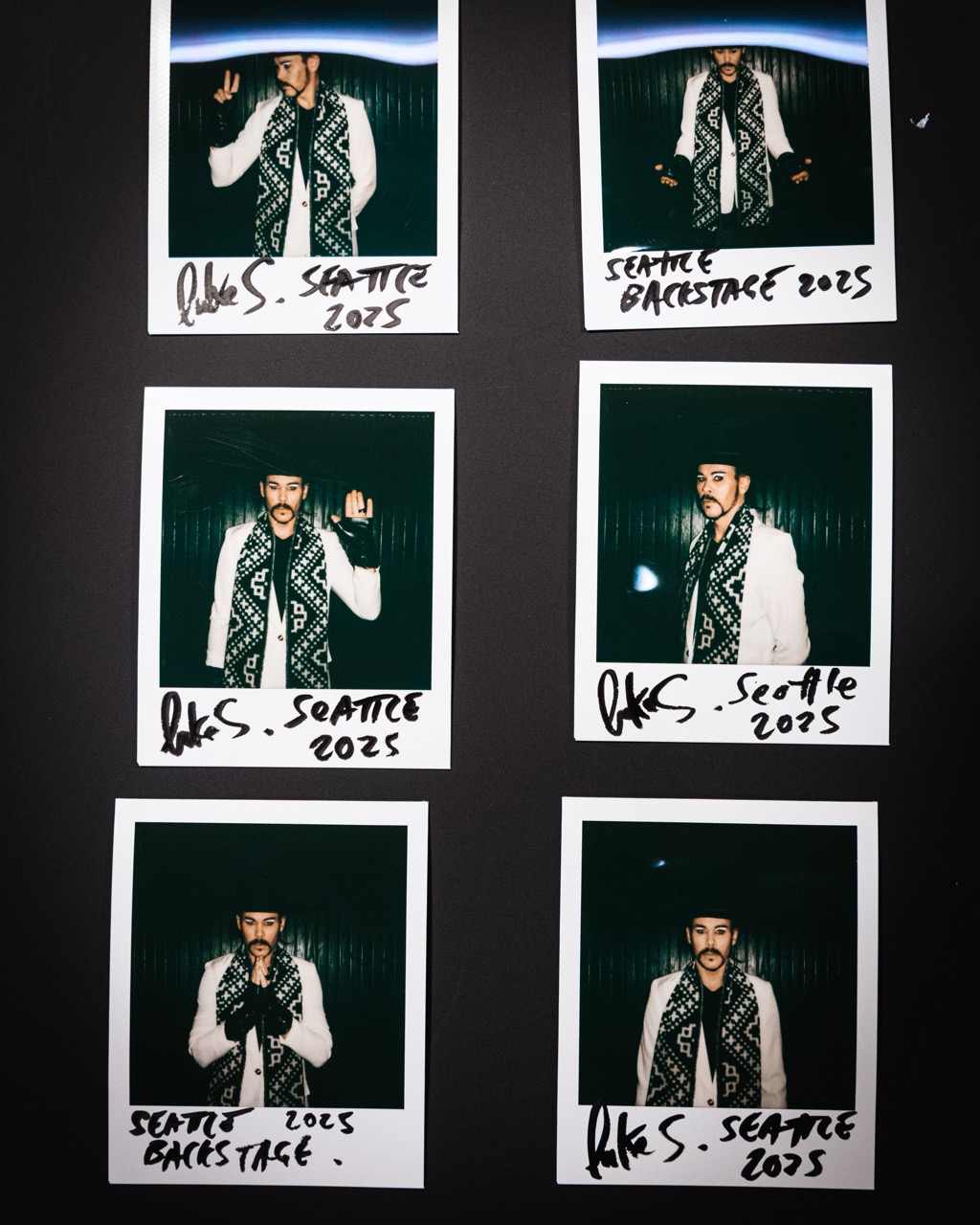

It’s dark out when Slick Rick swag-walks his way out onto the platform, and in the time that spans between this moment and the end of the festival — which is not very long — he exhibits what is, very likely, the most industrial use of about ten or so minutes any of us in the audience has seen from a live act in quite some time. In the minutes immediately following the festival’s closing, Pitchfork’s Alphonse Pierre tweets: “Lmao saw slick Rick get on stage perform 2.5 songs flash his chains and dip exactly what I expected fire.” And he’s right — at this stage in the game, if anyone’s legacy speaks so loudly for them that they don’t have to do much more than have their name printed on a showbill to invigorate thousands, it’s Slick Rick. In the one shaky video I have of his set on my phone, he’s leading a sea of frontward-facing cameras in a spirited “Go Slick Rick, Go Slick Rick, Go!” The thing about it is, aside from these fifteen seconds, I don’t remember anything from when he was on stage. Executed like a true legend: much like the brand of lyrical storytelling he spearheaded in New York’s hip-hop genesis, the only way to experience it is, and was, to be in the moment.

The community-first crux of Young World is personified when, as the legions of cultured teenagers and twenty-somethings file out from the matted grass, some of the acts on the bill are among them. (On my way out, I make eye contact with a perplexed-looking man with an afro in a red T-shirt, only to realize a second later that it’s Jadasea.) After hastily purchasing what I think is a blueberry “Fruit Barrel” drink — four hours later, all of the ice in my water bottle is still ice, and I’ve just spent a majority of the show desperately licking away at the few liquid droplets the insulation let slip — I take a seat on a bench, where I realize that the drink is, in fact, an alcoholic spinoff version of what I initially guessed it was.

Of the voices belonging to various pairs of feet shuffling in front of me, some include a pair of old-heads (maybe the Candy Crush players?) that groan complaints about the brevity of Slick Rick’s set, a stroller-pushing mom flanked by two pesky kids, a group of teenagers who screech through a smoke-infused debrief, and straggling pedestrians on late-night phone calls. It’s another testament to the family-first mission of MIKE & Co: there is no one-size-fits-all demographic valued over the other, and with the door for communal enjoyment open wider than ever, any — and every — one is both allowed, and encouraged, to take part in the moment. Somewhere in the middle of performing “Aww (Zaza),” the earworm smoker’s anthem six tracks deep on his latest LP Disco!, MIKE leads the audience in a spirited call-and-response: “Stuck in the midst of it all… Struggling? Nah.” One of youth’s most effective selling points is the ability to outright reject any implication of the struggle — too young to think about college, too young to think about rent, too young to think about dying — and in this moment, as everyone in Herbert Von King Park turns a collective back towards their problems, the world represented on this fabled patch of grass certainly isn’t old.

Midway through putting off a dreaded 20 minute walk back to the Inwood-207 St Subway station, I am joined on the bench by a group of snazzily-dressed teenagers who, it soon becomes clear, are longtime Instagram friends meeting in person for the first time. Through shy laughter and polite outfit compliments, they awkwardly arrange themselves in the little sitting room they’re afforded — until I leave for the subway so they can have the whole thing — and work through a haphazard plan to tackle their first night as a unit together. From TisaKorean’s silliness to Junglepussy’s spell, every contagious thing besides monkeypox tonight has been carried through autonomy — the same brand of it represented by a newfangled friend group for whom, an hour or so to midnight, the fun is just beginning. Five hours after Young World's sweat-soaked start, the words of the bald record industry figurehead from Alvin and the Chipmunks continue to ring true: the only rule is that there are no rules.