Love Is All You Need

LOVEISENOUGH, whose work has been featured in Vogue, Architectural Digest, T Magazine, and more, has always been something of an enigma. Their identity eschews eponymous branding for a dreamlike title that calls to mind a line from a letter or a film script more than the title of a design firm.

And this is exactly what Daye had in mind when she first named it: “I’ve always felt so comforted behind a pseudonym like LOVEISENOUGH, because it's less of a brand and more of just a message. But it's not even original: It's from a poem by William Morris. So it's kind of invisible. It's like borrowing someone else's identity in a way.”

“Love is Enough” by William Morris

Love is enough: though the World be a-waning,

And the woods have no voice but the voice of complaining,

Though the sky be too dark for dim eyes to discover

The gold-cups and daisies fair blooming thereunder,

Though the hills be held shadows, and the sea a dark wonder

And this day draw a veil over all deeds pass'd over,

Yet their hands shall not tremble, their feet shall not falter;

The void shall not weary, the fear shall not alter

These lips and these eyes of the loved and the lover.

This kind of sentiment — that design can be driven by a message — isn’t new, at least in the context of design history. Highly influential historical institutions like Archizoom Associati and the Bauhaus have always been driven by a message or a feeling: larger ideas like “Superarchitecture” (Archizoom) or “Functionalism” (Bauhaus) guided their work and can be seen to this day in their enduring legacies.

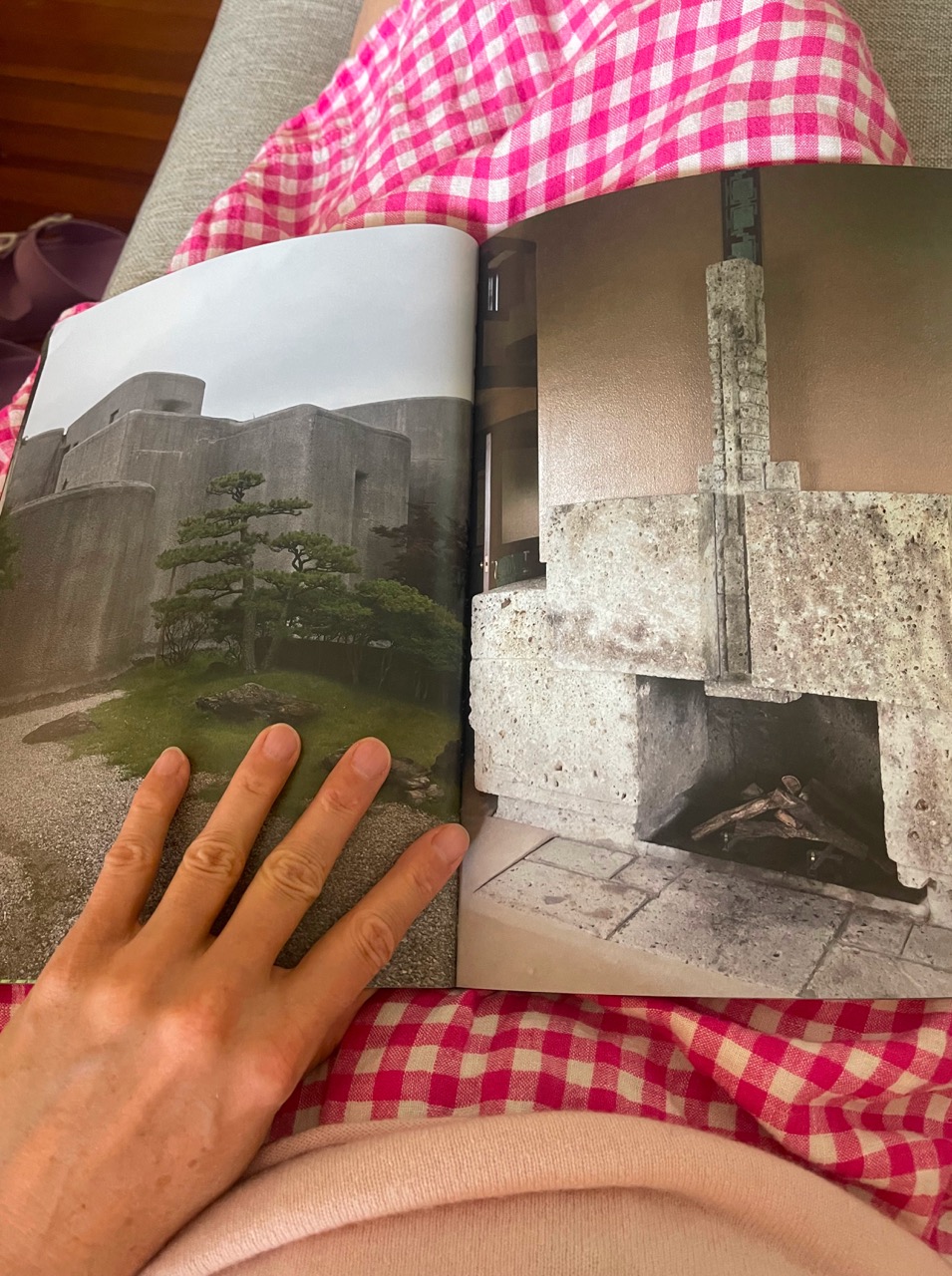

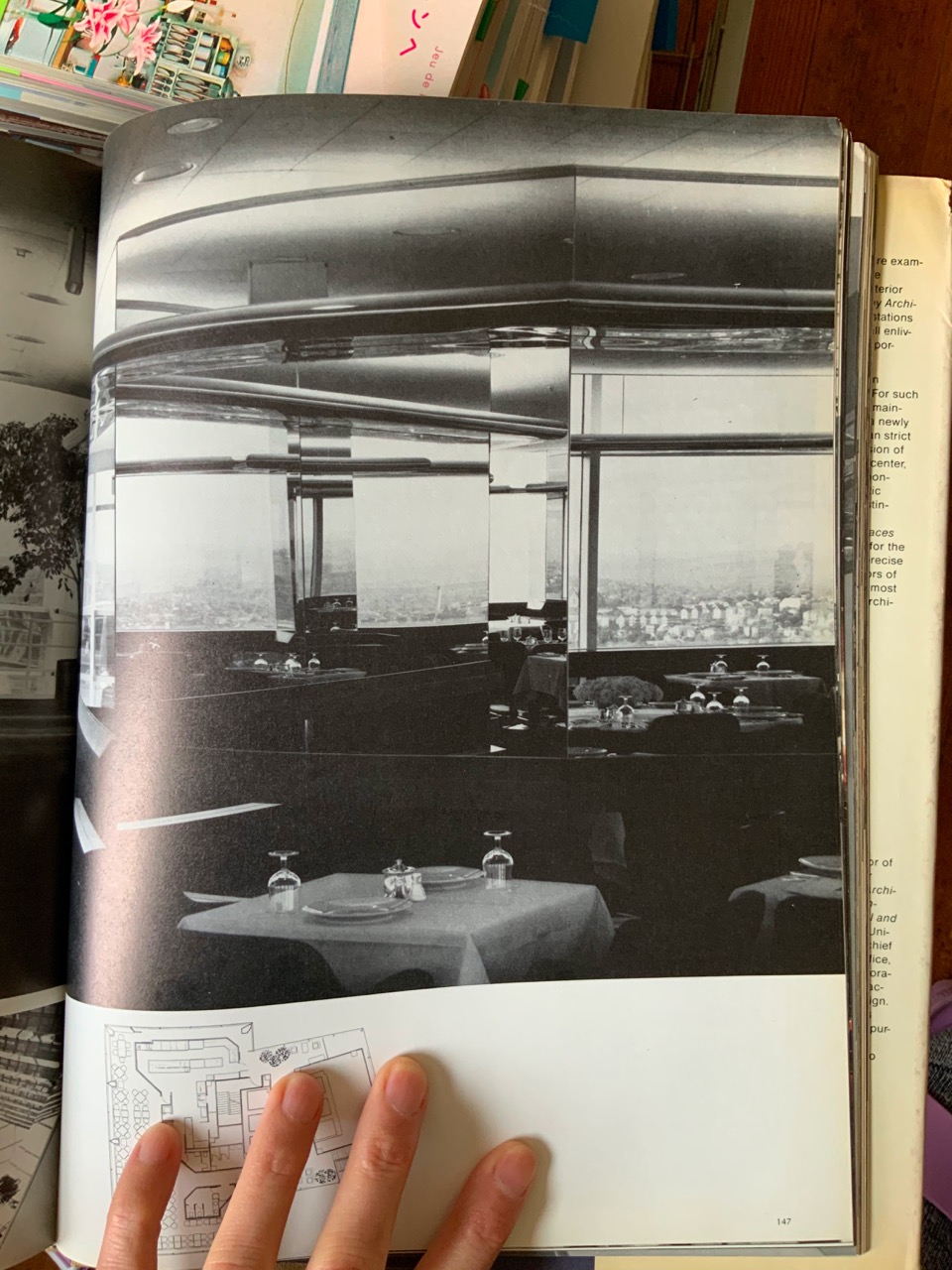

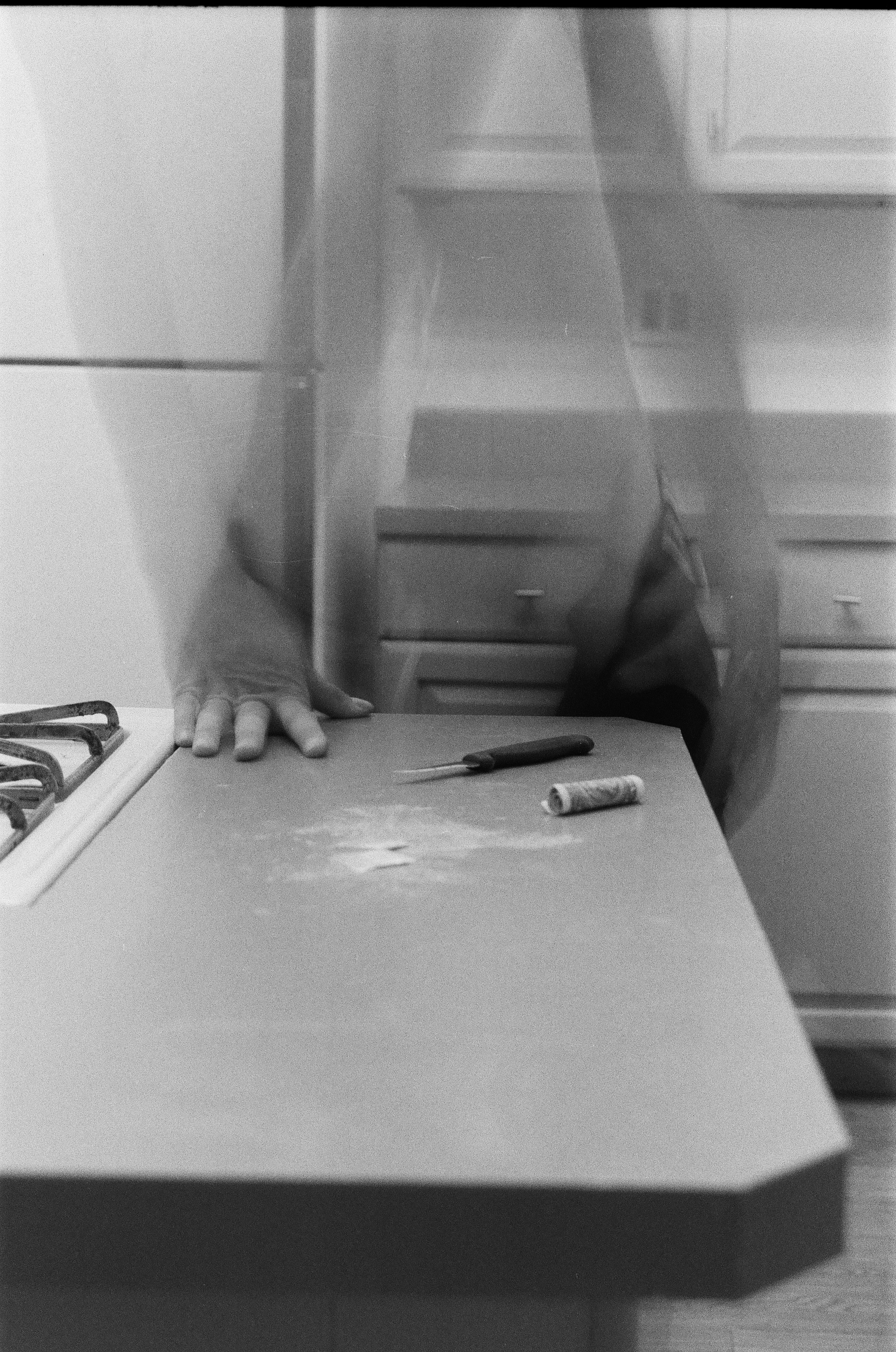

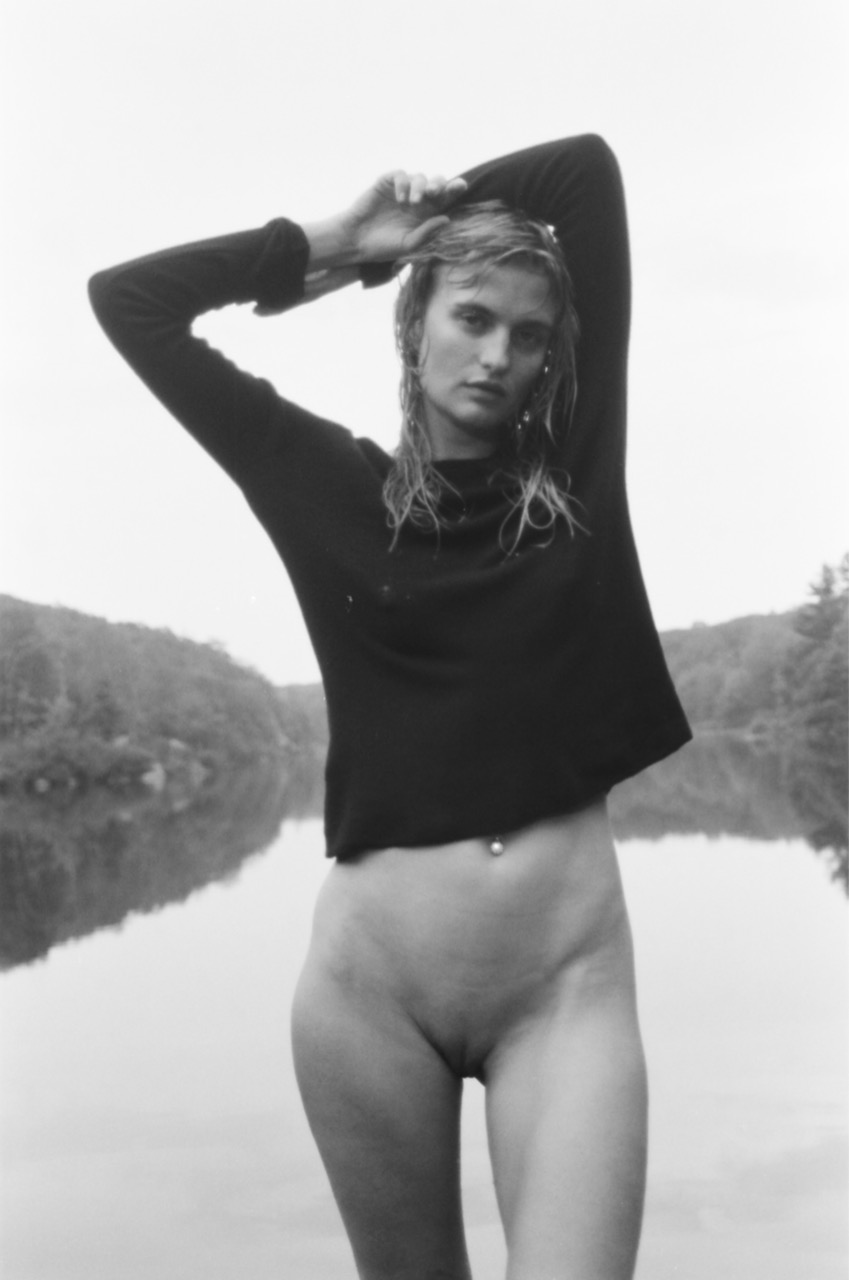

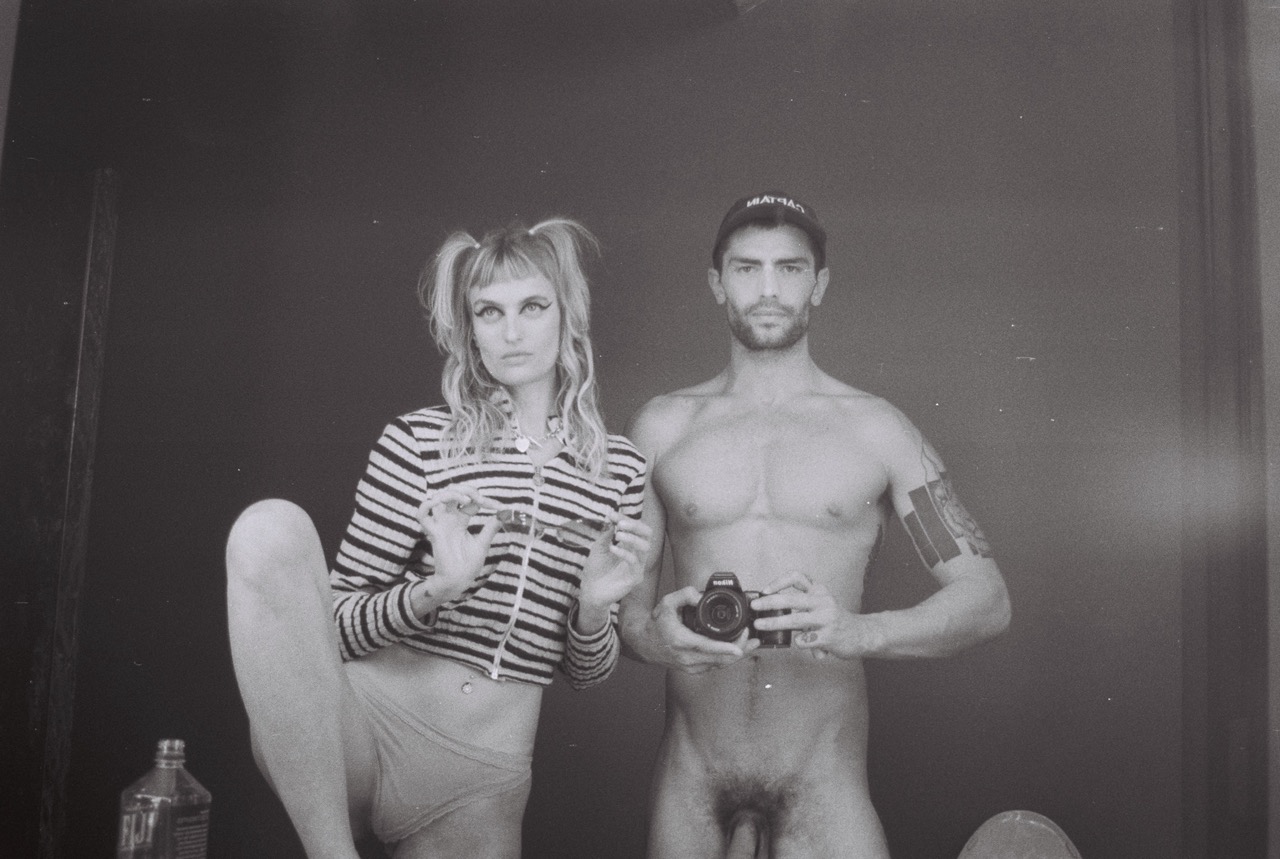

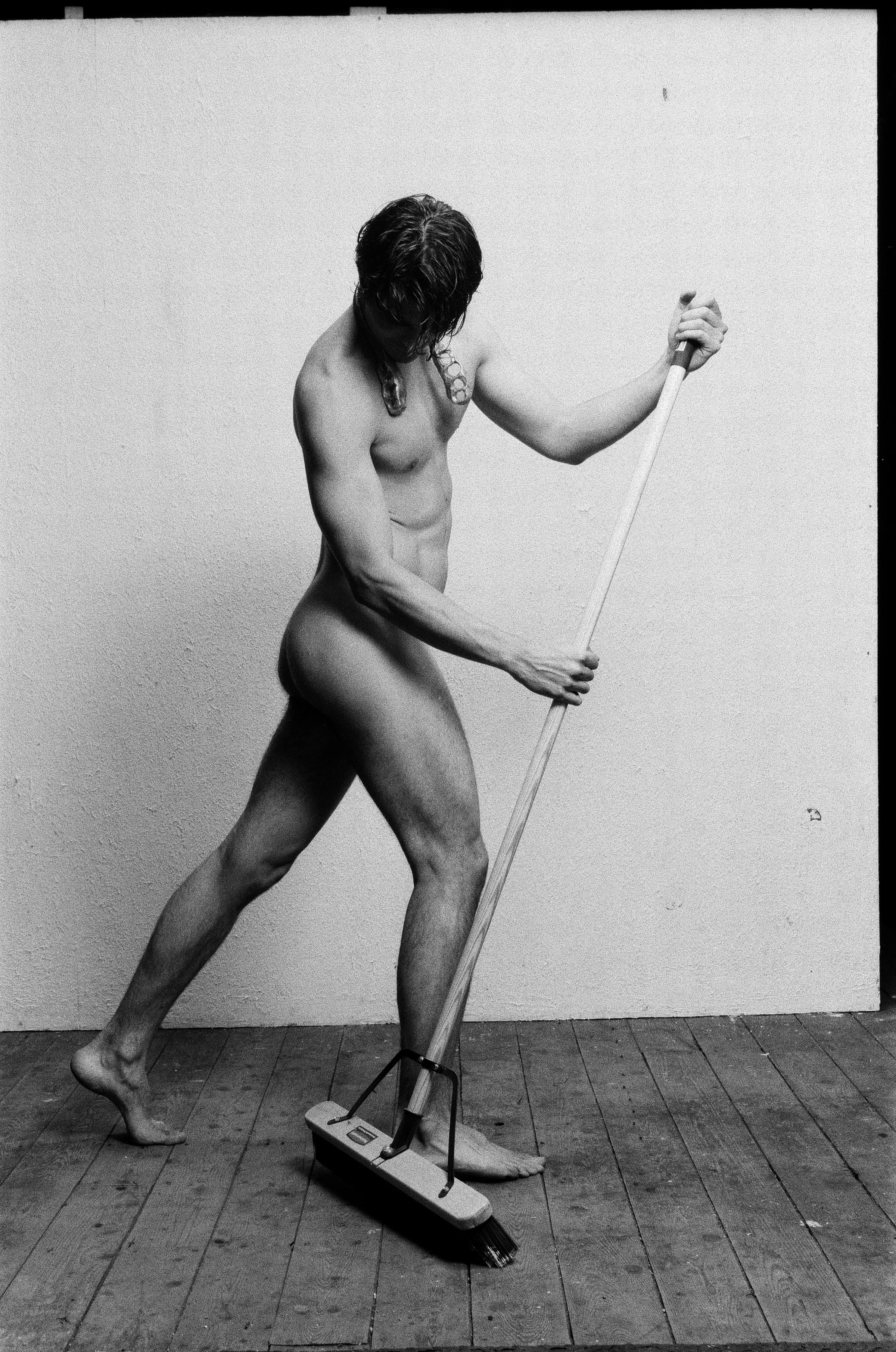

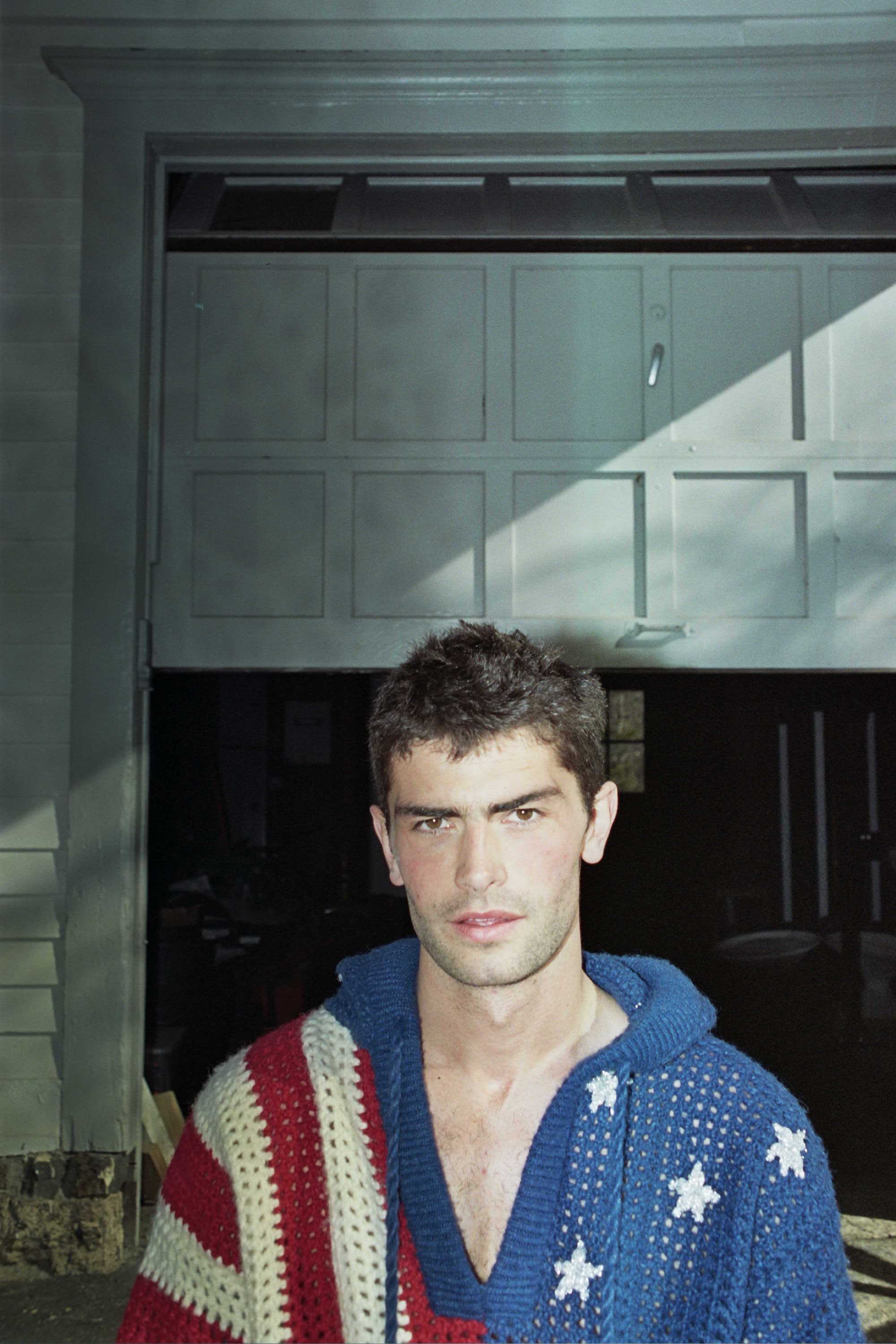

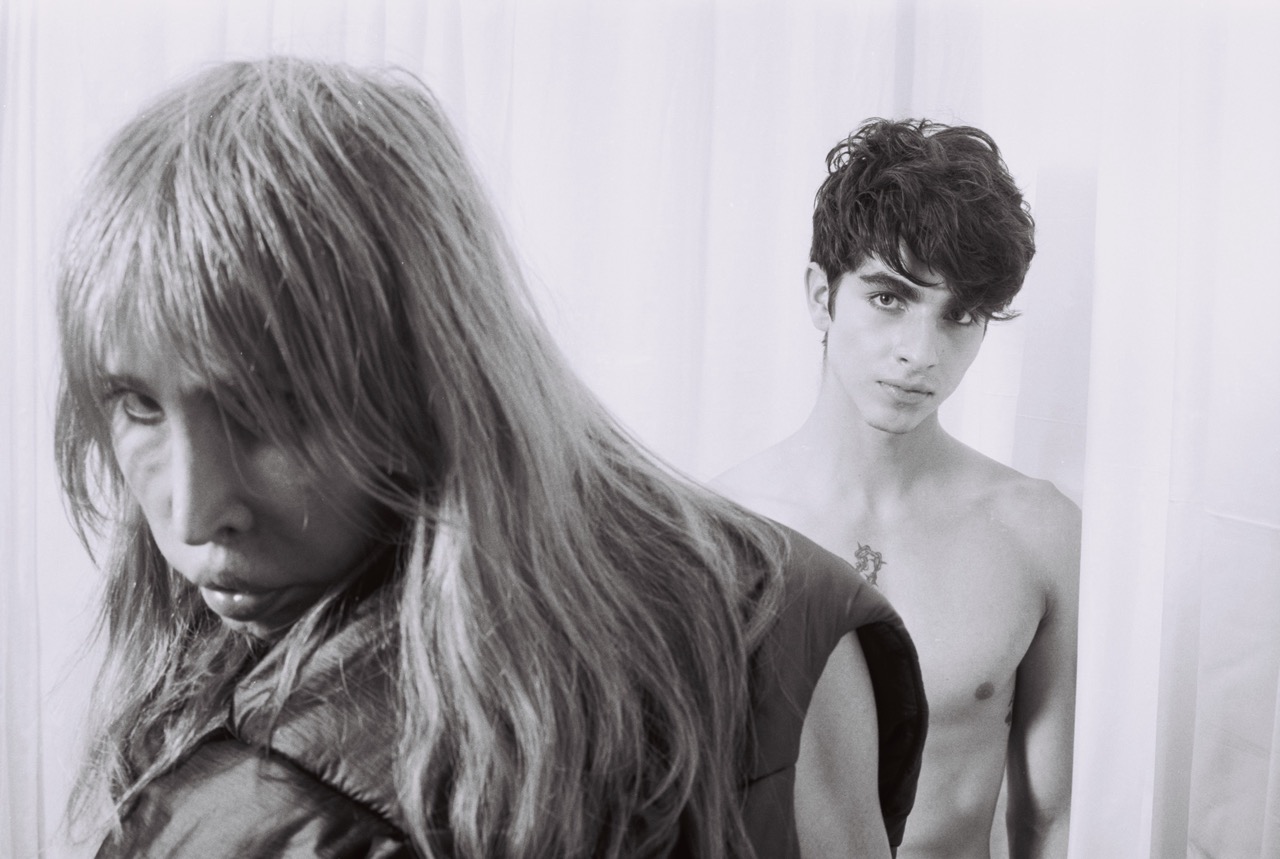

New York residence by LOVE IS ENOUGH — Photos by Marco Galloway

At its heart, design is the embodiment of an abstract concept. Its true magic lies in its ability to crystallize an idea, transforming it into a tangible entity designed for daily life.

But what is this message — this idea of “love is enough”? For Daye, it seems to come down to a generosity of spirit: an orientation toward creating design that embraces the human experience and isn’t afraid to grow alongside it. One look at the studio’s work and you can see this in action: terrazzo made from discarded brick that recycles history into something new, walls that embrace their natural roughness and form myriad shadows when the light hits, wood that reveals its age like a badge of honor.

Texture in its own right is a sign of humanity, as Daye tells it. In the age of “aesthetic”, creating spaces that are meant to be experienced firsthand is something bordering revolutionary.

“If we just think about the human body, in 3D space, and all our sensory aspects of how we perceive space, you get to a deeper intuition: what feels right or wrong or what is right or wrong,” shares Daye. “These instincts have been built over hundreds of thousands of years … and that's what makes someone like Gaetano Pesce’s work [special] — and [the work of] many of our other peers and friends who are making things that are not so much in the realm of like conventional tastes, but have this textural element: you look at it and you want to touch it.”

“I remember teaching at Pratt and one of the students at the end of the semester was like, ‘You know that you pick up every sample and smell it?’ And I was like, ‘Oh my god, I do do that.’”

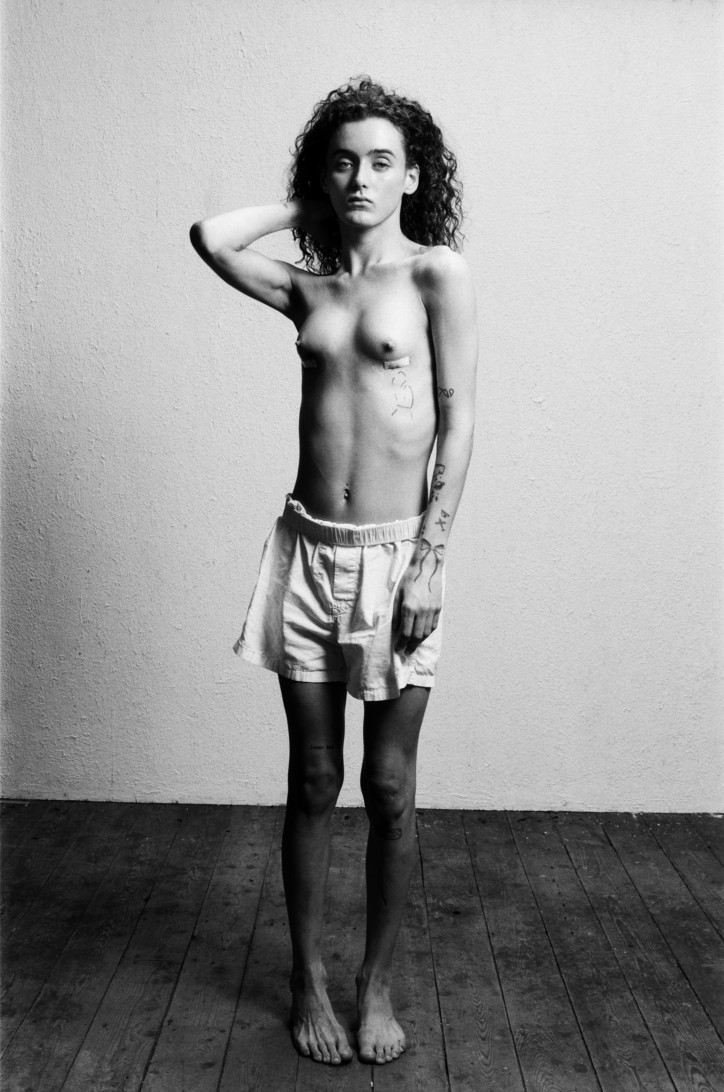

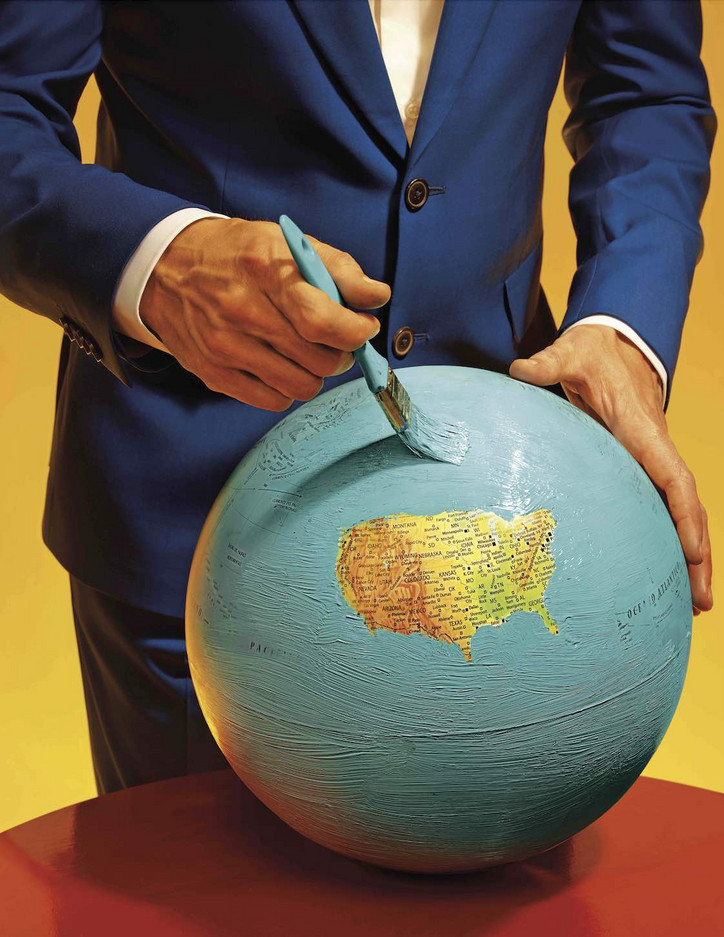

For the designer, this level of personality in design transcends even the physical. The integration of identity as a core design principle is of high value for Daye, who views our unique self-conceptions and histories as integral to good design. “There’s so much diversity in the world — I wish there was more identity expressed in design. We could bring in so many influences if we didn't just default to the white male European [style], like just Corbusier."

At the end of the day, it comes down to challenging the status quo: having a growth mindset rather than a fixed one. And same goes for the studio itself as they undergo a kind of rebrand. “[We’re trying to] make it reflect more of the spirit [of “love is enough”]. I had made it all very cryptic when I started the studio — now we’re ready to turn a little more outwards, to be more apparently open.” For Daye and the studio, this has looked like sharing a wide range of influences on social media. But as far as the name goes, she still values the message-driven aspect of their identity. “I want to have myself for myself, and not be a commodity. It feels almost sacred to hold [my name] back.”

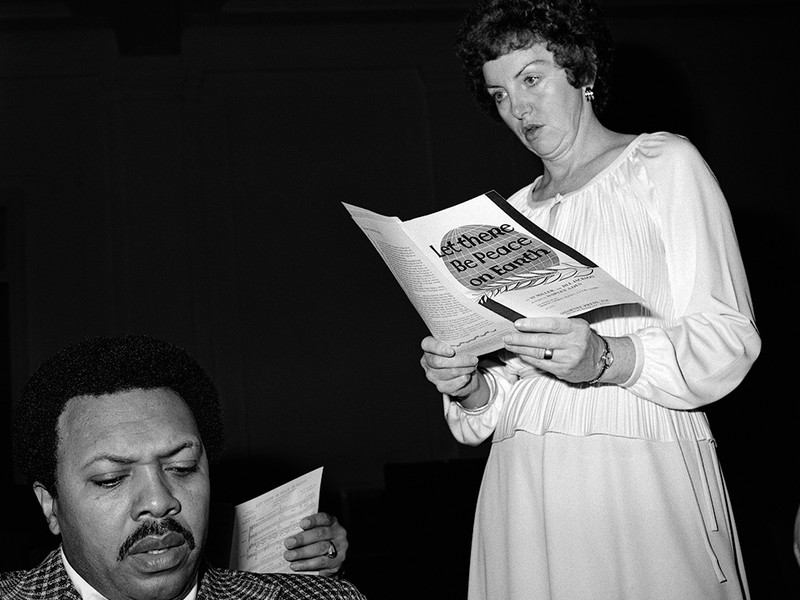

Hers is a sentiment shared by many. In the midst of all the fluff, there is a very real influx of very authentic design expression, both online and off. Design exhibitions here in New York are just as likely to take place in a Navy Yard workshop or Bushwick loft as they are in a Chelsea gallery. One of our twenty cover stars for this issue was the icon Gaetano Pesce himself. Young furniture makers find themselves invited to fashion shows and downtown parties, and makers eagerly share their DIYs on social media and beyond. The energy is infectious — the future is full of promise.

And the key to it all? Always trying something new. As Daye wisely put it, “Hey, what if I broke that rule?”