Means of Production

The warehouse, home to Sheerly Touch-Ya and Shisanwu LLC, are both headed by artist and Lunch Hour member Serena Chang—the former being her family’s first American enterprise upon migrating from Taiwan, the latter being her sculpture fabrication studio. On May 18th, within the context of these entities — charged by layered histories of artistic labor, material culture, fashion commerce, migration, and manufacturing technology — Means of Production opened the Sheerly Touch-Ya warehouse to the public for the first time in its history. The night of performances from a slew of artists, activists, and creatives was just the beginning of an ambitious eight-week exhibition run, which included an art workers’ town hall on June 8th, and an upcoming film program Out of Circulation organized by third Lunch Hour member Lily Jue Sheng on June 29th.

Behind an industrial metal door with vinyl lettering “SHIS NWU” (the “A” has fallen off), I slip into the Sheerly Touch-Ya warehouse on opening day, the entryway opening into a tiered industrial space full of palettes, plywood, pipes, and metal scaffolding. A thrilling slippage between what is an art object and what is warehouse environs sets in: is an open bag of sweeping compound a work of art? Maybe. The open book on a worktable, or the spectacles on a styrofoam block, with twigs for arms? Probably. Artworks tucked between boxes of hosiery, left unannounced on the concrete floor, or strung up on the rungs of industrial pallet shelves offer an invigorating disorientation.

Works in the show are not clearly demarcated from warehouse supplies — echoing the thesis of the project, which brings focus to the hazy lines between precarious and acknowledged, waged and unwaged labor. To this point, Linh explains, “Our subversive decision to present artworks in a warehouse, rather than a white cube or museum, challenges conventional notions of art and authority. It raises questions about what constitutes art and who has the power to define or value it. This setting infused our project with humor, playfulness, and a sense of freedom — elements that artists and art workers rarely experience today.”

Around 5pm, a group of performance artists begin to wander the entry room with intention, winding small handheld radios while an audience gathers. Performer and choreographer Anh Vo’s Common Fetish calls on a wide list of citations including “Vietnamese possession rituals, Communist propaganda, Nicki Minaj, Jacques Derrida, Christina Sharpe, Thich Nhat Hanh,” among others. At times evocative of a Buddhist chant, a Catholic prayer, a rodeo speech, or a pledge of allegiance, the performers Anh Vo, Kristel Baldoz, Kris Lee, and Nile Harris engage in a call and response. “I am a hole for you to penetrate,” they speak in unison while transitioning from floating independently to a ritual circle. As the procession of performers and audience members trickle deeper into the warehouse, down a dark aisle of boxed stockings, Ethan Philbrick plays the cello in deep bellows and sharp picks. Some clothes are removed and the script becomes darker. Movements become less rhythmic, more rattling, more haunted. The push and pull of performers and bodies, in both possession and dispossession, signals to the interpenetrating nature of the sexual, the spiritual, the psychic, the political, and the somatic all at once.

Artist and writer Amy Ching-Yan Lam then begins a live reading of seven large printed posters lining a hallway near the warehouse entrance, with words based on conversations she has had over the past seven months with herself and others. Equipped with a laser pointer and microphone, Lam reads off “Top 20 reasons why I’m not withdrawing my work or participating in a boycott against Israel or other corporations, organizations, or states that are complicit in the ongoing genocide of Palestinians” in a biting, flat delivery, one of the stated “reasons” being “WHY ARE YOU ATTACKING ME?” Shooting through bullet points, Lam ends on the posters, “Top reasons why I let these beliefs poison my solidarity with Palestinians,” the only reason listed: “I don’t know.” “Top reasons why I don’t know” — “There’s no good reason.” It feels like an apt answer to many contemporary questions we are mulling over.

Deeper within the warehouse, Erik Nilson activates his work Oothecean Stanchion by climbing on top of the pallet shelving unit housing his textured, all-white tableaux of wood, plaster, stuffed stockings, and HDPE shavings. Descending into the work, Nilson begins pulling a chain rig, hoisting a large section of a tree upwards, breaking apart from the chalky installation. Nilson tinkers with piezoelectric microphones, amplifying the clinking and clanking of chains into a feedback of electronic drone, punctuated by the wailing of a small amp on the other side of the unit. He mans a drill augmented with a white branch, twirling and kicking up shavings, finally mixing concrete and water into the mold of a white tree stump. As a sculptor and fabricator, Nilson’s performance echoes his professional work, laying bare the residues of material transformation.

In the back of the warehouse, artist vinacringe enters nude, standing behind stockings stretched across the metal scaffolding of a pallet shelf. A high pitch soundscape falls to a low pulsing hum, transitioning to a breathy narration as vinacringe ties stockings taut across their body. “You have gifted me a wound in the shape of the world,” the audio whispers. In a frantic catharsis, they cut through the stockings on them and the scaffold with a large knife, and on their knees, they send out a yell to release themselves from the performance.

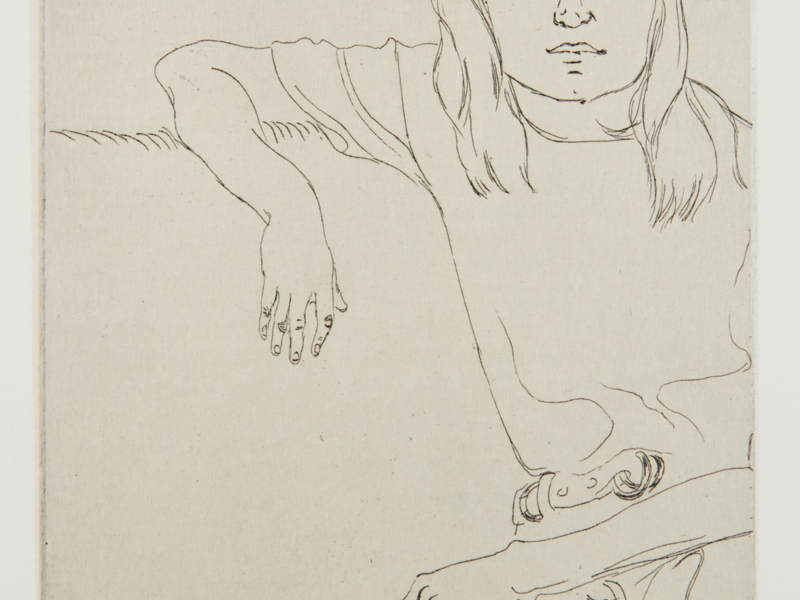

Finally the crowd makes its way to Tianyi Sun’s work Dream Skin (Sheerly) consisting of reclaimed windows from the warehouse, referencing Chinese folding screens (or pingfeng), collaged with Sheerly packaging and hosiery. In a site-specific reading, Sun reflects on stages of production, the working body, and the hidden nature of creative labor, peppered with Mandarin.

Tianyi Sun, Dream Skin (Sheerly), 2024, photography by Tallulah Schwartz

With the conclusion of the performances, we free-wander the dark alleys of pantyhose boxes, soaking in the sense of discovery. The works, too many to name, each address the show’s themes in subtle or oblique ways. Tra My Nguyen’s diaphanous textile-silicone figures, collaged with Sheerly tights, converging realms. silicone dreams, reference histories of Asian garment manufacturing, and especially forms of labor exploitation therein. Especially considering Balenciaga’s recent plagiarism of their master’s thesis, Nguyen’s suspended sculptures summon issues of authorship and the appropriation of creative labor, especially that of BIPOC artists and designers, as well as the opacity of foreign manufacturing to American consumers writ large.

Serena articulates this intersection well: “Means of Production for me, was to engage the conversation around labor. How labor is often deflected onto others (intentionally or not) within our capitalist society. In the setting of the hosiery warehouse and sculpture fabrication, the opposing worlds of mass production and unique sculpture fabrication is the ideal setting to address this conversation. In this age of globalization where labor is hidden and objects can be ordered and delivered the next day, our collective understanding of labor has become so obscured.”

Most crucially, Means of Production offers a refreshing model for exhibition organizing and curatorial method. Really, you could call it a non-framework — built around site-specificity and free-form engagement with it, full creative agency, collective organizing, and a generosity of resources. Every artist who applied to the open call, Lunch Hour tells me, was accepted. The show’s loose concept — applicable to all — allowed for multifarious interpretations. The curators’ and Shisanwu’s volunteer effort fundraising from the public as well as their pocket money largely made the project possible. In Lily's own words, "...so much [funding] is tied up with weapons manufacturers, the non-profit industrial complex, predatory real estate, the state, and mega corporations. It made sense to experiment by self-organizing collectively and in a big way, since that’s how labor power is organized, right?"

The biennial-scale Means of Production ironically feels minimally produced, which is perhaps entirely in line with its mission. In the time of W.A.G.E. for cultural work and growing consciousness of the tentacular ways in which racial capitalism constitutes our contemporary world, the project’s unstructured nature seems perhaps the most congruous response to such questions: in a contemporary capitalist work-relation, how does immaterial labor become economized? How does art and the self become commodified? Are these actually the same question, repackaged?