Lucien Smith: A Constant Return

On display at the Parrish Art Museum through January 2021, Lucien chose to feature the paintings to represent his philosophy that “artists don’t need gallery representation to reach the career milestone of an institutional exhibition.” Perhaps easier said than done for an artist that has made more money from his art before turning thirty than most artists will make in their entire lives. However, Lucien has decided to use his power and much of the profit from selling his works to benefit the non-profit he began, Serving the People (STP), an online curatorial platform, “which offers support, programming, and a commission-free sales platform to artists internationally.” STP, still in its earlier stages, aims to bypass the boutique auction house system by allowing artists to independently curate their work on an online platform with no commission costs. STP is a heavy departure from a career of what many critics have described as self-indulged projects of disingenuous grandeur, but for Lucien, it is everything; it is, in his own words, his “Mona Lisa.”

Lucien Smith takes a Zoom call with office to ruminate over the Rain Paintings and discuss the return to an old form as he dedicates his life now to expanding past the world of paint. He’s wearing a gym shirt and a bright pink bandana which he uses as his COVID mask. After a quick, personalized, whispered audio tour of the museum and up-close-and-personal time with the Rain Paintings, Lucien steps into the museum manager's office. He removes the bandana to reveal a charmingly unkempt beard and a bright smile that hardly leaves his face throughout our long conversation. I ask him how much he would like to speak. “I love to talk,” he quips, “so as long as you can take it.”

Lucien reflects on the last few weeks; at the time of our interview, it is mid-August and his show had been open for about a week. He seems overwhelmed with emotion over presenting these aging works, all of which he owns. “I struck a chord, obviously,” he says about the Rain Paintings, “and I think at a very early age, I made a historical body of work.”

Like many other creatives across the arts, Lucien found fame in the early 2010s through an internet followings and by capitalizing on brand culture. “I did my first lookbook for Supreme when I was still a junior in college,” he says, “I did a cover for this Canadian magazine Bad Day Magazine that they shot it in my sophomore studio at Cooper. I was a little showboaty about it, I was proud of it, you know, as anyone would have been.”

Even before the Rain Paintings were close to conception, Lucien was making a stir with his sense for creativity beyond the antiquated systems of the art world, but once his senior show premiered and he was introduced to the life of auction houses and galleries, he held confidence that had both the potential to manipulate as well as to be manipulated by the art world. “I did not know how certain things could hurt my career or not,” he says. “Obviously with any sort of haste for success comes the handful of criticism and outside opinions. And as a young kid, you know, that was just a lot for me to deal with. It quickly became about money and all this other stuff and not about the art.” Imagining myself, or any of my twenty-something artist friends that I consulted before this interview, receiving as much money as Lucien did for his paintings at our age is nothing short of nonsensical.

In many ways, Lucien was deprived of the growth that comes with seeking institutional successes over the career of artistry. “Most artists spend their whole lives, you know, maturing during their work and maturing themselves and then get to a point of recognition,” he says. “I didn't. I wasn't able to have any of that. I wasn't ever able to sit with work and decide if I liked it or not.”

When the Rain Paintings first premiered, they were quickly chastised by the art criticism world as being disingenuous attempts to make fast cash; one major blow to Lucien’s reputation was a piece in Artspace by Walter Robinson where he coined the phrase “Zombie Formalism”: “‘Formalism’ because this art involves a straightforward, reductive, essentialist method of making a painting […] and ‘Zombie’ because it brings back to life the discarded aesthetics of Clement Greenberg, the man who championed Jackson Pollock, Morris Louis, and Frank Stella’s ‘black paintings,’ among other things.” No matter what you, I, or even Lucien may interpret this critical classification to suggest, or even if it was a good or a bad designation at all, art snobs ran with it. “People would come up to me like while I was eating dinner and scream at me and call me a zombie formalist,” he says with a laugh, “People read these art blogs and shit, and then they go out there believing this crap. It was too much for me to deal with.”

Lucien had little time between his experimental, flashy moments in college to being featured on lists, brandished with art world commodified labels, and classified by people who had existed in his new world for longer than he had been alive. “I had sort of lost belief in myself and what I was making,” he says. “So I had a little bit of a breakdown, a meltdown, you know, I wanted to self-destruct because I wanted to destroy the thing that I built, as this sort of façade and dive into some, you know, identity crisis and to figure out like who I was so that I could come back in a moment like this and be much stronger in my foundation and be able to handle criticism.”

To many, going from a hungry art student to international recognition in the elite circles of art curation is a dream, but for Lucien proved to be an unexpected challenge in a lifetime dedication to art. In art school, they teach you how to find ways to make money; no class explains how to handle the stresses of becoming one of the youngest artists in the Whitney biennial. However, Lucien isn’t shy about his participation in the speculative art world nor does he deny his lust for the recognition. “I wanted to be the youngest artist to ever to sell a work in auction over a million,” he says. “A lot of what had happened in my early career was definitely my own doing, don't get me wrong. You know, it was just a little of a, ‘Be careful what you wish for,’ sort of situation. With anything in life, you have to take what you're given and turn it into what it is that you want or need. What I can say is that I've been given a tremendous amount of insight and perspective on something at such a young age that I still now have thirty, forty years ahead of me to create something special, you know, from a, from a unique position.”

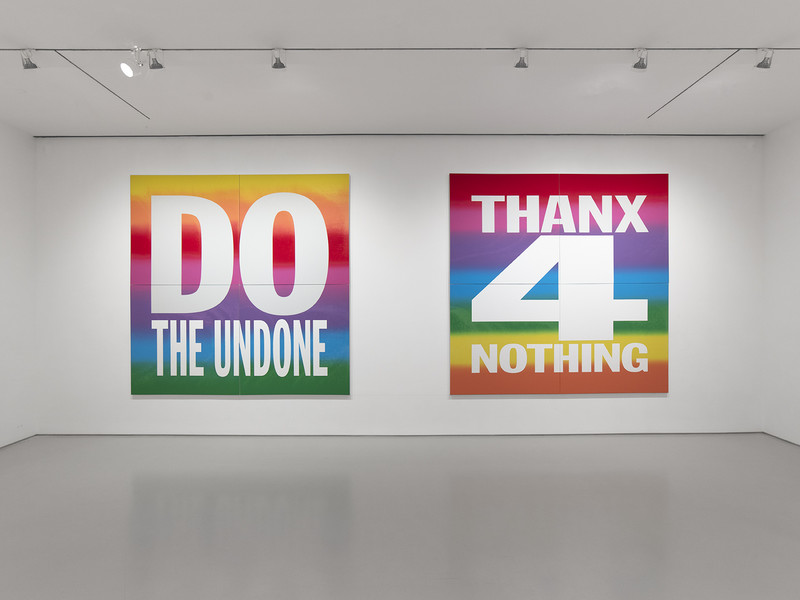

Lucien created the Rain Paintings after deep processing with considered inspirations and mood boards. He describes the paintings as autobiographical, emotional depictions of the feelings he held inside at the point of creation, pulling past works or contemporary inspirations together according to personal synthesis. "I don't just make stuff so that I can make money,” he says. “The art that I make are things that I just want to see out there in the world, little breadcrumbs that I want to leave.”

For Lucien, finally, the work can receive the air and space to be considered outside of the politics of the gallery space and auction system. I think the work deserved the opportunity to be seen outside of a commercial context,” he says. “That's what a museum is. That's what an institution is. It doesn't care about how much money the paintings sell for, it's just about the integrity and the quality of work.”

After many years in the spotlight, in the face of criticism, and as a sort of creative butterfly all over the art and design world, it is a point of healing for Lucien to present the works plainly as paintings from the artist Lucien Smith.

At this point, I mention to Lucien something peculiar that I noticed while researching him: I wasn’t able to find even one article that mentioned his race, and if he found it as peculiar as I did. “I mean, shit, man. I'm glad you brought that up,” he says. “I've been thinking about it a lot, definitely because of what's going on in the world today. I come from a mixed background, you know, my mom is Asian. My dad is African American. I've had to move to so many different schools because of my parents' situation that I was thrown into so many different identities, you know, like going from public school to private school, playing sports, and being more art-oriented. I've always been a chameleon sort of way, adjust to the demographic of my surroundings.”

Lucien speaks on his attempts to address his relationship with his race and the distance he had with it when he was younger. “I'm not proud of that,” he says. “it wasn't that I was a fraud as a kid, but I feel embarrassed, like when I was in Louisiana, why wasn't I just myself, why did I act like I was more into sports than I am, you know? And it was just because at an early age I was moving around so much that I was never really able to form a real identity, you know? Every moment that I finally felt like I was becoming who I was, I would be thrown into another situation. I would get lost and I've kind of carried that with me. I think that is why I have never been able to identify as a person of color, you know?”

Lucien believes that, because of the sort of racial ambiguity he adopted throughout his childhood in his attempts to fit in, he wasn’t restricted to racial expectations. “I've been able to live my life free of some of the stuff that other people who are of color have to go through,” he offers. “I have always tried not to include race in my art because it's not really who I am, you know? I want to make my art and what I'm doing accessible and inviting. I understand that other people want to make theirs as a means to open up a window into their perspective. And there's nothing wrong with that. There are just two different types of ways of creating."

As we are currently living in a time that systemic racism and the ways race pervades through all systems of western capitalism have been brought to the public sphere, Lucien has begun to rethink his place in his art. “Looking back now during all this stuff, I'm starting to wonder if that was the right thing to do, you know? Am I not being true to my roots and my heritage? I'm not making Black art, you know, because I'm not fully Black and I'm not making Filipino art because I’m not fully Filipino. I think about it all the time. I'm not shy or embarrassed or insecure about my ethnicity. I just don't think it defines me. And I think that that has transferred into my work and has allowed people to perceive my work outside of just my identity.”

Lucien points to Black artists like David Hammons, the legendary artist who has been a defining figure in not only postmodern form but in our modern understanding of what is possible in art creation. He acknowledges with respect that artists like Hammons and his attention to race is not only essential to his form but adds to his revolutionary nature. Though, Lucien’s paintings, to Lucien, is about Lucien, and he’s not trying to claim any more than that.

I ask Lucien if he thinks his abstract form and the absence of any overt mentions of race in his paintings have anything to do with his early embrace from the art world, as artists of color, more often than not, are left out of the conversation of transformations of the American canon. Lucien, categorically, does not believe the art world embraced him at all. “I would think of it more like Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader. They’re intertwined but they're always battling one another.”

For someone that has had success as great as his, especially his financial success at such a young age, it’s hard to believe that the art world doesn’t like him. He begins to concede that perhaps there is truth to the assertion that his color-blind attitude toward his art may have affected his success. “I feel much more like an outsider, you know, even though it may not appear that way,” he offers. “I've never felt welcomed. The art world to me is like twenty-five people who I can name, who don't like me very much, you know? It’s hard for me to say.”

I offer that perhaps his choice not to include race in the Rain Paintings in favor of an adherence to abstract expressionism was in a way a rebellion against what the art world expects from an artist of color. Lucien then reconsiders and begins to suggest that he felt uncomfortable bringing his race into his art as he never felt the effects of racism personally enough to justify including it in his artistic expression. “I'd probably get in trouble for this, but I just didn't want to play the ‘Black card.’ It just didn't seem right to me because I didn't grow up with a lot of that.” He is more concerned with issues like poverty or education access, issues that are not exclusive to communities of color. Although, he does stand firm that the art world does not do nearly enough to address economic or racial issues and in many ways perpetuates them. “I've seen the inner workings of the upper echelon,” he says, “and I understand why art is so wealthy or is so speculative because it's the bragging rights. It's the highest you can go. There are cars, there are houses, there's real estate, but then it's like, ‘I own this many Andy Warhols or this many Basquiats, you know?’”

To Lucien, art and politics are intertwined because of the elite’s obsession with high art, and the ignorance that artistic institutions perform only reproduces the inequality in the art market. “I don't take art that seriously,” he says, “and I don't take people in the art world are markets that seriously, but they should be taken seriously because they are involved with people who decide how our lives are run.”

For someone so against the functions of the high art world, it’s somewhat confusing that Lucien has ever been a pariah for the accusations of intentionally making art to be “flipped.” Although Lucien has made a considerable amount of money from his art, his art has at times sold exponentially higher on the secondary market, profits of which go to auction houses. Bearing in mind the confusing relationship Lucien has with this system, both benefitting from it and objectively being exploited by it through the secondary market system, it’s no wonder he began Serving the People. “STP, in other people's words,” he says, “is a creative incubator and digital platform. It was born out of necessity. It was born out of a lot of the lessons and a lot of the shortcomings that I noticed in my field, which is fine arts.”

Though much of Lucien’s creative life has been in the realm of confusion, drama, and controversy, it has born in him a precise and focused revolt against the corrupted art market he was exploited by. “Someone once told me that an expert is someone who makes the most mistakes in a very narrow field. I think as far as art's concerned, I can call myself an expert in some way. The paintings and the stuff that I was making were self-servicing, but I think art can serve a wider demographic. And I feel like my paintings weren't doing that. And so, I wanted to take the knowledge that I had and give it to others and allow them to use me as a platform. And so that became STP.”

He doesn’t view STP as self-servicing in the way his paintings were; he receives that outlet these days through his film work. He has several projects on the way, including a challenging, if not concerning in its nature, film from the perspective of a disabled person. “It's the type of movie where I think a lot of people will walk out of the theater,” he says, gleefully, “but I think that's the point.”

No matter what any of the critics from the past may have written in stone about Lucien, it would be difficult to paint a wide brush against STP and call it formalist in any sense of the word, for its entire purpose is to break down a system. It would be naïve to write STP off as another successful creative attempting a half-baked attempt at charity work. It’s obvious that STP, to Lucien, is a sort of magnum opus; he wants to change the art world and it is what he wants to be remembered for. In his own words, he wants to be a “cultural entrepreneur,” though what exactly that entails is yet to be known. Is it Tumblr 2.0? Is it Craigslist for art? And will it be big enough for such a powerful force like the boutique auction house system even care? It’s yet to be seen. For now, though, one thing has been made clear: the Lucien Smith that first created the Rain Paintings in 2011 is not the same Lucien Smith that has put the same paintings back up on display in 2020. For an artist who achieved fame at such a young age, he will inevitably be engaged with a constant return.

“I’m not coming back into this, in the second phase of my career, or whatever you want to call it, to do the same thing again,” he says. “I’m working on my next trick.”