MAVI's Life of Service

In the time it took the 24-year-old Charlotte rapper to record this album, the third of his career, he struggled with finding the right name for it. On the day of its last recording session, MAVI enjoyed a card game with a girl he often played with. She asked him to sign the card on the top of the deck, so he did. “MAVI is in New York working on his untitled album,” she then wrote on the card. “I'm going to keep these for your shadowbox,” she added after. Ding ding ding.

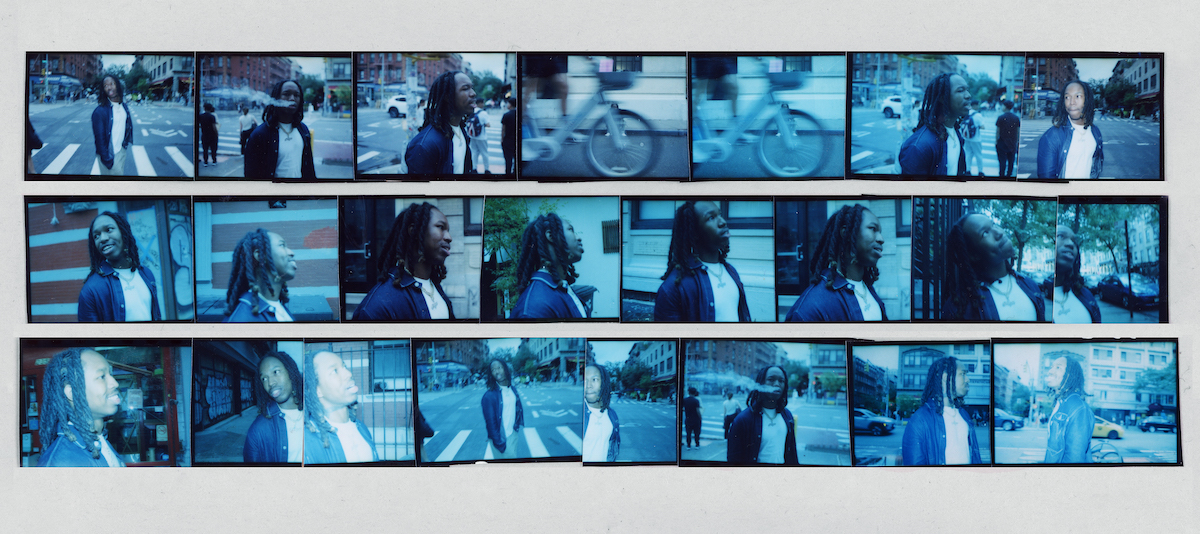

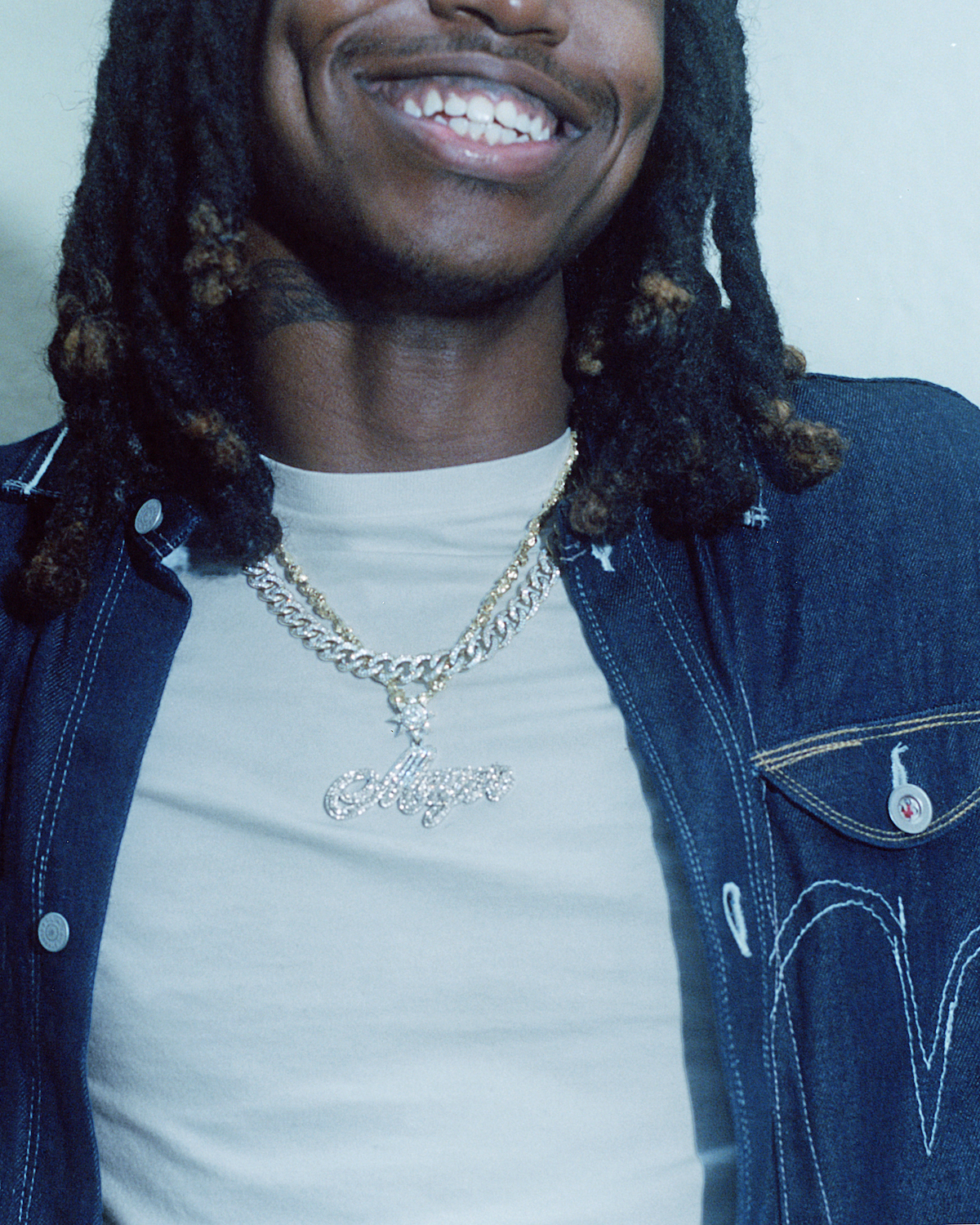

As MAVI now sits across from me outside of MUD, an earthy cafe in the East Village, his voice cuts through sounds of clinking glass and neighboring dialogues, illuminating a watershed moment for the most methodical piece he’s ever worked on. “When she said that, it was like, ‘That's exactly what I've been making,’” he muses. “I've been putting all of these different failures and triumphs and experiences into this fuckin’ 3D frame for people to play with.”

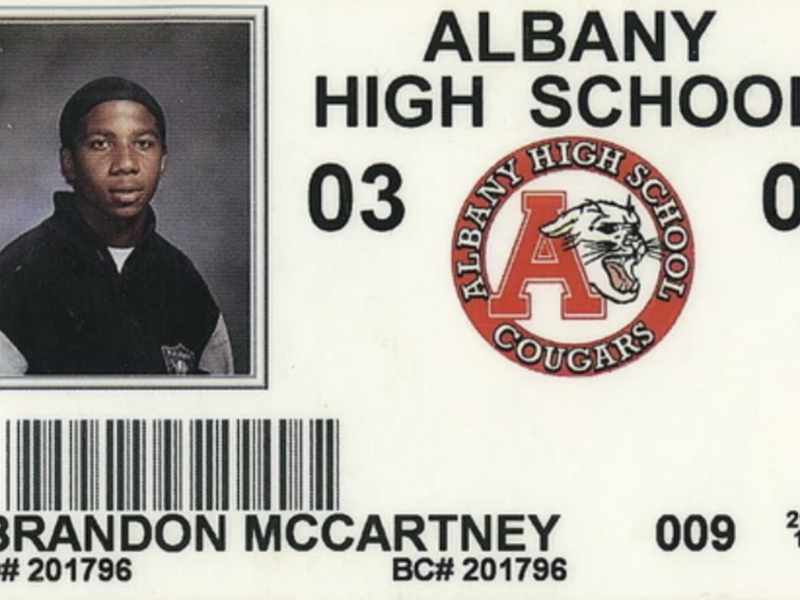

MAVI is patient and measured with his words despite Manhattan’s incessant racket, never really raising his voice until the conversation opens up to shared laughs and colloquialisms. Even then he remains even-keeled. When he's not contextualizing his music, he paints pictures of his future away from it: One day he’ll jumpstart his nonprofit and give out free laptops to kids in Charlotte. One day he’ll teach biology where he once attended high school. One day he’ll be revered for much more than the words he’s spoken into a mic (even though he plans to keep rapping 'til he's dead). Among other things, MAVI opens up to office about his appetite for literature, the friendships he's built through music, and the process behind shadowbox.

Olivier Lafontant— How do you feel like this new album is a continuation of you processing the interpersonal struggles you’ve gone through?

MAVI— I think for this one, I was making the songs because of a lot of chaos happening in my life at one time. And I was making the songs to document what was happening so I could try to map out the lesson or the message of all these events in my life. And so that became the backbone of the album, the path that was drawn through [me] being pulled in so many different directions.

Something that’s a common theme in your work, especially this time around, is how meticulous and artful your rollouts are. I've seen the art pieces that you’ve been posting on your Instagram, for example. How do you feel like the visual components serve as companions to the music?

I wanted to craft a language — like an aesthetic language. So things being carefully arranged, things being voyeuristic throughout the album, me speaking from a removed perspective about myself; these are all things that I wanted to visually express through shots in the music videos or things like the tracklist or the tour poster. And then also because I'm talking about things that are cyclical — addiction, love and loss, transformation — I wanted to display it in a systematic way. And then also being really tactile: The album cover is a platinum/palladium print and it was mastered on tape. Adding a degree of physicality to everything, [like] having an incense that comes with the vinyl [has been important]. These songs are all things that happened to me those days that I made them, and then over time they’ve become like a photo album.

What do you hope to accomplish with this record?

I want people to make this record their own, feel humanized through it, and humanize me through it. And I want people to stand in front of the painting, even if they don't read the placard, even if they don't buy the painting. Just stand in front of it and feel moved. Because I think moving people is the one thing nobody in music marketing or music strategy really thinks about. It's like, how do we take this music, whatever the music is, and then get people to move as a result of it?

Could you describe a transformative experience that's happened since the release of your last album that's helped inform this one?

Oh, man. I’ve had a lot of transformative events the last week. I've bought a house since the last album. I broke up with the subject of the last album, got with somebody else, and broke up with them. One transformative event has probably been going to Paris, going to their modern art museum, and really understanding [that] I was overthinking art. Me thinking I was not informed enough to understand art prevented my access to being moved and building relationships with artists and art, on the visual side. So I removed that barrier, and that's when I really started to take in design and digital art as something I can understand, play with, and leverage.

Was working on this album the first time you had that much of an influence on the artistic side of things?

Definitely. A hundred percent.

Something that really sticks out to me is when an artist like you is so poignant about the vulnerable experiences a normal person may be ashamed to display on a pulpit. How do you accept that? Does that weigh on you while you’re performing?

When I first started rapping I didn’t want my mom to know I was rapping. And not because rapping is something she would not want me to do, but because of how I was rapping about my own life. And that there were things that I felt empowered by sharing with millions of strangers that I was afraid to share with my mom in that same naked way. So I definitely have run-ins with my own vulnerability in ways that are not just a super warm hug all the time. But I think it's worth it for me because it helps me understand myself. I can rap something that I can't intellectualize and then draw meaning from the rap song. So it's therapeutic, cathartic, whatever. You know?

I definitely feel like because you take that role in your music, the listeners take in what you give out and it helps them contextualize what they go through. Do you feel an obligation to do that, or is it just a natural outcome?

I don't think I feel an obligation to it because that would make me eventually grow to resent doing it and resent the listener [as well]. And I don't think it's something that's necessarily natural to do either, because it's more traditional in rap music to write about stuff that makes you feel cool. But what I think it is is a kindness on my part, like a loving act. That's how I think about it. I need my listeners. Even if it's one of them or two of them, I need them. And because I need them, I will allow them to use me and my story to better love themselves. I think I can go to heaven off that.

Speaking from personal experience, Let the Sun Talk was an album that I played a lot during quarantine. I feel like having that level of companionship, even if it’s through somebody you don’t know, is a crutch.

Right! We’re friends! And that's the thing about Let the Sun Talk that makes it special, even beyond anything in the music, is the context. So just being there for people when it’s relevant is also a part of the mandate for me to [do this], you know? To be there at the right time in the right way.

On shadowbox, you only have one feature on the record. How intentional is it for you to give yourself as much space as you do when it comes to tracklisting and putting out your own work?

I’ve never had a rap feature in my entire career. I kinda don’t know how to make songs with — well, I know how to make songs for people. You can give me the space and I can give you something really great.

Even “EL TORO,” [Earl Sweatshirt and I] made that separately. Like Ovrkast sent us both the beat and we both sent in a verse on the same night. And [Earl] was like, “Yeah, we're doing this.” I don't really know how to rap with other people that well. One thing I want to really do, I wanna do a “friends tape” 'cause I have so many rap friends, and we have so many songs. Because even when we think about [James] Baldwin or just art in general, the community that art established is almost cooler than the art itself. Like there's this photo, I think it's like Basquiat, Grace Jones, [Keith Haring], and like Fela [Kuti] or some shit. That shit is hard. Just that everybody's art is in communication with each other's art is one of the most rewarding parts of learning art history. So I’m definitely trying to get better at that. I think there’s one person who’s ever outrapped me on a song, and that’s MESSIAH! He’s my final boss. But other than that I don’t think it’s happened.

Not even Earl?

What you think?

I do love your verse on “EL TORO” so I mean…

Okay, thank you. But also I don’t think he would ever try to kill me [on a track] though. Me and him it’s like… You know how Darth Vader at the end of Star Wars with Luke, he kind of let himself die, forreal? [Laughs] On some torch-passing shit? The nigga be on some torch-passing shit. But I really do want him to try to beat me. With him specifically, the song where he tries to beat me up and I try to beat him up back, that would be the Earl Sweatshirt/MAVI song to come out on my shit.

What does the context have to be for y'all to get to that point?

I don’t know bro! I don’t think our relationship lends itself to that. And that's part of the thing too, like, think about it like this: Do you know me and MIKE have rapped together one time? It was the first day we ever met each other, we was at Sage [Elsesser]’s house. Me and MIKE never even came close to making a song after that. But it’s ‘cause I really love these niggas. I go out to eat with them, we do other things. We ain’t even establish our relationship in the studio.

Isn't it strange that the common thread is the music though? Do y'all ever talk about that?

[Earl] kinda impressed upon us the importance of us being leaders. We building individual castles in this kingdom. Sometimes we be having a lot of shit going on. Like me and MIKE just did our first show ever in London. That shit was cracking. I’m kinda saving [the collaborations] for myself now. It’ll be historical. It’s like if DOOM had a Madlib beat on Operation Doomsday, maybe Madvillainy wouldn’t have hit so hard.

You’ve mentioned before how it’s really important for you as a rapper to keep reading books. What are your favorite things to pick apart from the literature that you read and apply to the music that you write?

I really like descriptiveness and detail. I was reading Sun Ra’s biography a while ago and it had a whole paragraph about this jazz nigga named Fletcher Henderson, whose music I don’t particularly like, but reading about him in the way they wrote it had me so intrigued. I want to know exactly what these songs that niggas is referencing sound like. That enriches my reading experience. It's like Harry Potter: they had the fuckin’ butterbeer shit. I had to have that shit.

On God, I wanted that shit so bad!

I had it! It’s fire! [Laughs] That feels so good! I love things that bring me into the world of the book.

There's a level of satisfaction that I get from reading a description of something that I didn't have words for prior to reading that.

Right! That’s all I wanna do as a songwriter.

Lastly, you speak a lot about the importance of your proximity to blackness, both physically and in terms of your family lineage. Can you go into detail about your attachment to your ancestry and how that informs how you carry yourself?

One thing about this album is it's rather churchy. “the sky is quiet,” “drunk prayer,” “open waters” . . . This idea of wanting to be cleansed in the water and the blood to be made new. I use the religiosity [from within] the tradition in my family to tell that story. I ain't pay my fuckin’ [Ancestry.com] subscription, but I've been making [family] trees, and I got up to like 1855, pre-slavery. My family, they're from South Carolina which is a huge slave port, but also damn near the closest thing we got to where black people sit still forever. When I was at the show in London, there was these pretty ass Ethiopian girls. And they came up to me and one of them was like, “Aw, your show was so good! Where are you from?” I'm like, “Yeah, I'm from Charlotte, but my family from South Carolina.” And she was like, “No, where are you really from? Like where in Africa?” I'm like, “I don't know.” You know what she told me?

What?

She said, “You should really try to figure that out.” [Laughs]