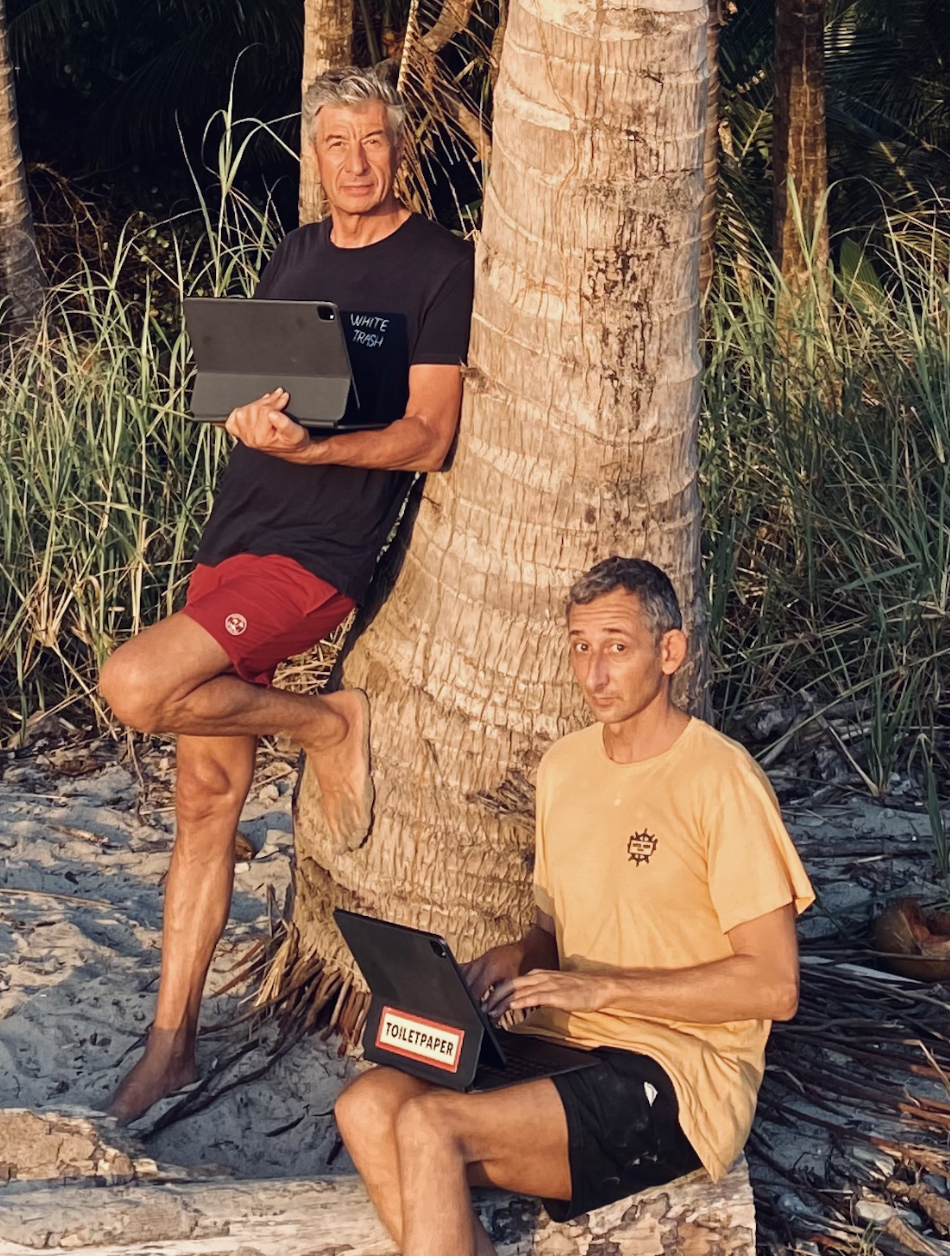

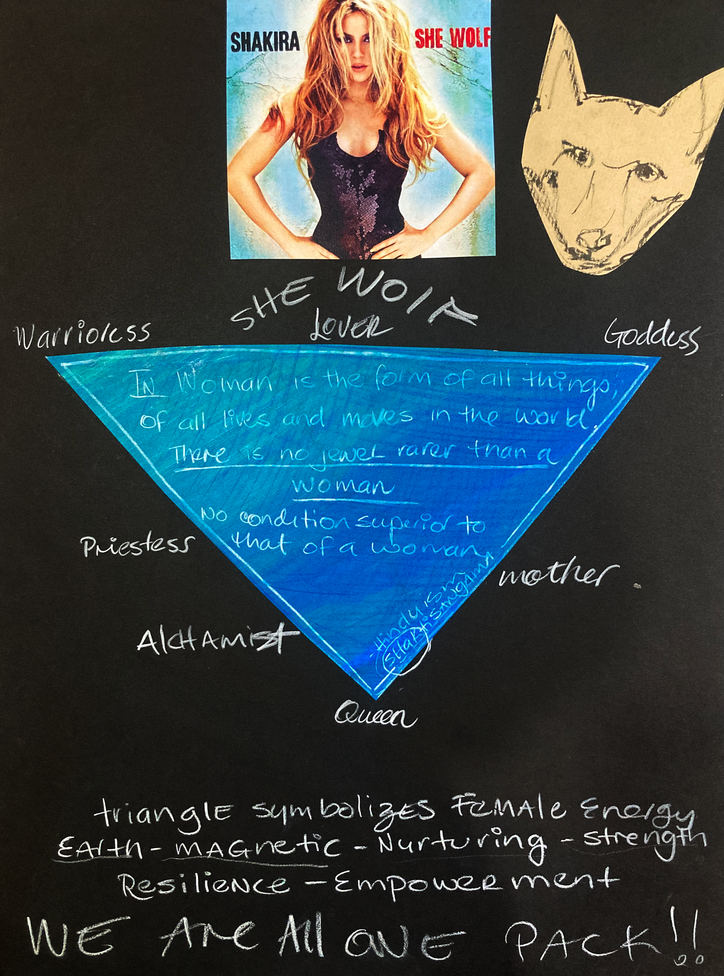

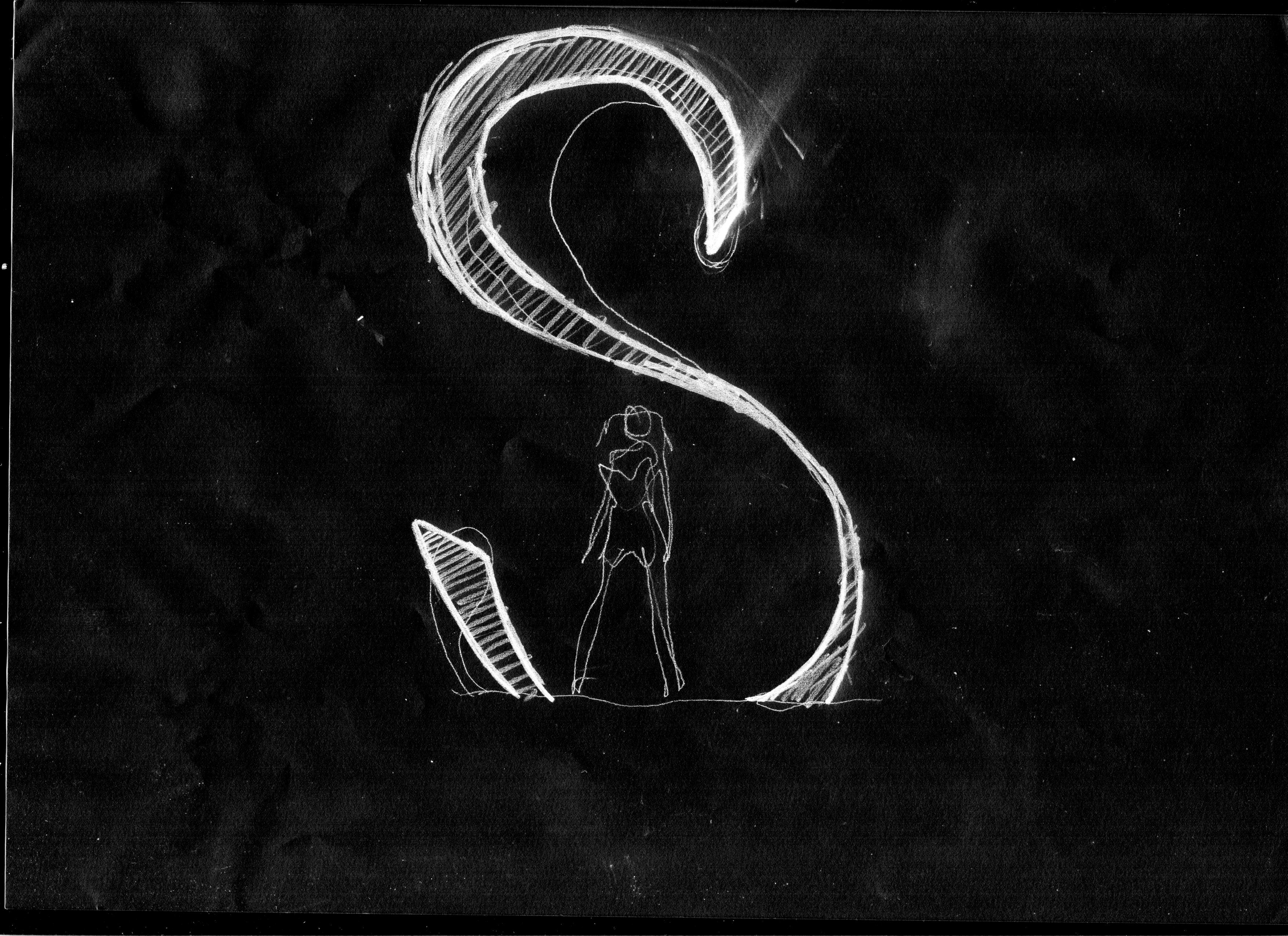

Maximilian Schubert's Doubles

Learn more about Doubles in our exclusive interview with Schubert below, and pay a virtual visit to the exhibition here. It's also on view at 120 Walker Street until May 30. And in tandem with the show, Schubert, Off Paradise, and Hassla are releasing a book that takes viewers behind the scenes of the latest exhibition on Tuesday, April 7 for $30. Named after the show, the book will include "Virus, Imposter, Infiltrator: Recent work by Maximilian Schubert, with a visitation by Felix Gonzalez-Torres," an essay from writer Randy Kennedy. If you're interested in purchasing, contact the gallery at paradise@offparadise.com or visit Hassla.

Why Doubles?

The title of the exhibition was initially referring to the double nature of much of the work, the contradictions embedded in the objects. When the work by Felix Gonzalez-Torres came into the picture, the exhibition title took on an extended meaning.

I read that you prefer to work in windowless studios alone. What role does solitude play in your creative process?

The space an artist works in invariably influences the work that's made there. I have two spaces in Brooklyn, one of those spaces does indeed have windows, but I don’t believe I’ve ever opened the blinds except for the window that houses an exhaust fan. Being alone is a great way for me to work through ideas, and out of necessity, it's become the way I construct the work as well.

Do you work in silence?

I think I’m similar to most artists in that I have music or podcasts or audiobooks playing much of the time while working. The silence comes after they’ve ended.

What overarching themes present themselves in this exhibition if any?

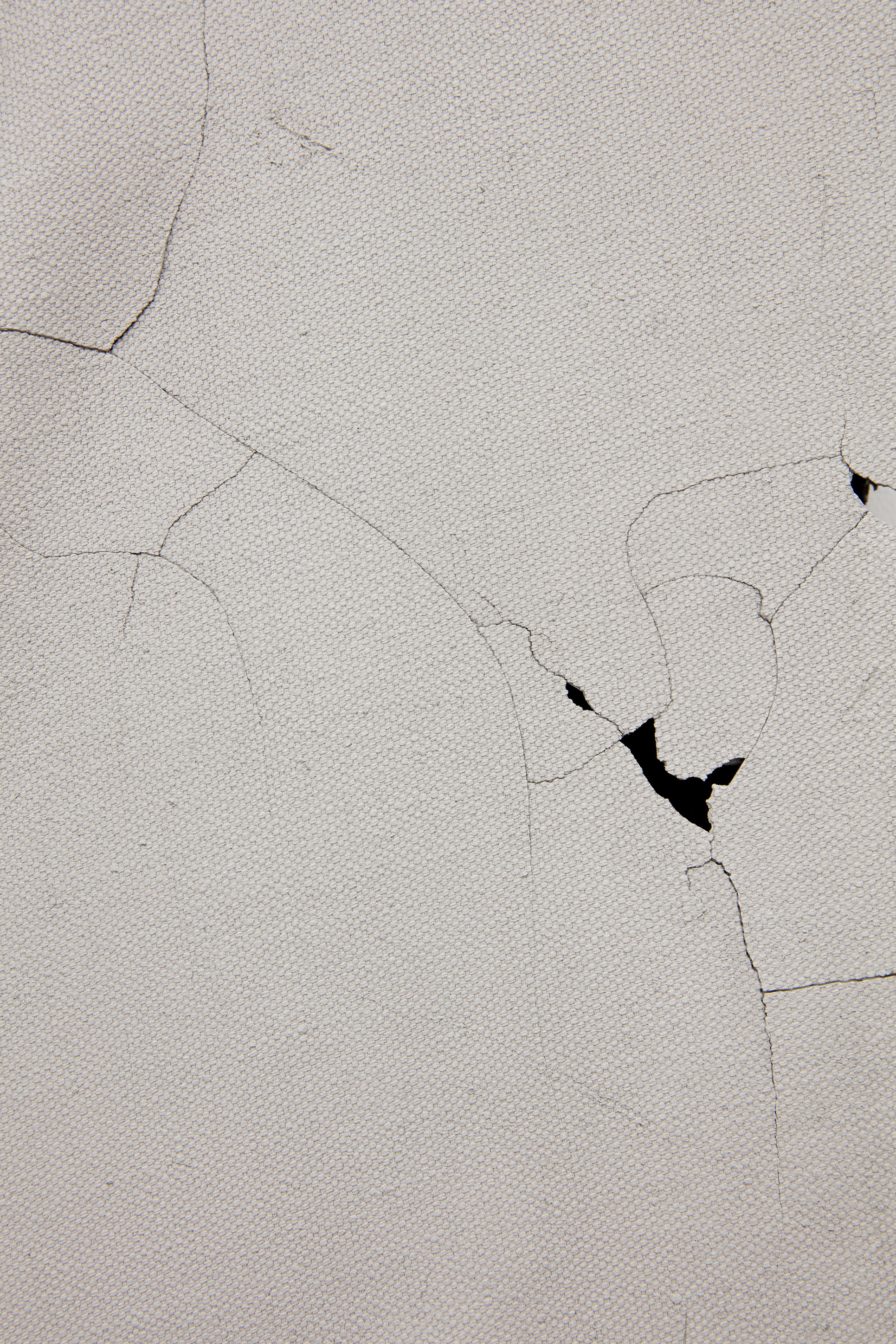

I think the theme that will be evident to a lot of viewers, at least initially, is the genre-bending of much of the work—the fugue state between painting and sculpture—especially the Untitled (fracture) pieces. I think the nature of the works—their objecthood—is something I can take for granted as their maker. But it's there for an audience to discover. Ultimately, I’m always trying to create a kind of tone or feeling that is highly specific to each show, an overall feeling you can recall when you reflect on being there.

You were loaned a fully sanctioned Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ work for your studio while you worked on your project. Can you describe the piece that was delivered to your studio?

Yes. The work was “Untitled” (March 5th) #2, 1991. The work is two lightbulbs, hung at a fairly high distance from the floor. The cords are knotted around a nail and the bulbs hang from this point, and the two plugs drape down to the floor and are plugged into the nearest outlet.

How long was the non-public public loan for? What were the exact conditions associated with the loan?

The loan was for a few weeks in February leading up to the show. The conditions of the loan were of course highly specific, but despite the specificity, there are a lot of choices one can make when installing the actual work. I was struck by how much was left up to me, and I realized there is an amazing amount of trust built into the work.

Do you feel like Felix’s work is fused into the identity of your work due to its presence in your studio? Did you find specific moments where its presence really influenced you? If so, can you describe those particular moments?

I think Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ work and oeuvre is fused into the history of art and will remain so probably forever. I can remember my first encounters with his work as a young artist, and it completely changed the way I thought about art. Of course, one needs their own approach and voice, but you carry these other perspectives with you, and his particular position has always been a touchstone.

As for what it's like to work around something like “Untitled” (March 5th), #2, it was in one moment something completely profound, and at another, simply an additional light source. I was always aware of it, because it gave off a warm light that contrasted with the colder overhead fluorescent lighting. The painting process in my studio requires the light be extremely consistent, so I had to make some adjustments while working. But beyond the practical stuff, there were of course moments where I sat back and just looked at the piece, just experienced it in a way that I couldn’t if it had been in a museum or gallery.

You mentioned that the unique stipulations for the loan were in line with Felix’s view on violating boundaries between public and private spaces. Is that something your work touches upon as well?

My work can never be both public and private like Felix Gonzalez-Torres’; the generosity and the true public nature of so much of his work I don’t think can ever be replicated. I hope my work is generous in that it gives one more than we generally tend to expect from art, but any decent artist hopes that. Art is obviously, above all, a thing of the mind, and there is a place where everyone sees the same objects, and then there is the experience they take with them, which is never the same. If you take a piece of candy away from a Gonzalez-Torres' pile, you’re really taking away, above all, an idea. I think a lot about how my work might live in the mind, outside of the gallery, which is ultimately where it lives most of the time.

Can you speak to your process of working with various materials like cloth/fabric versus metal?

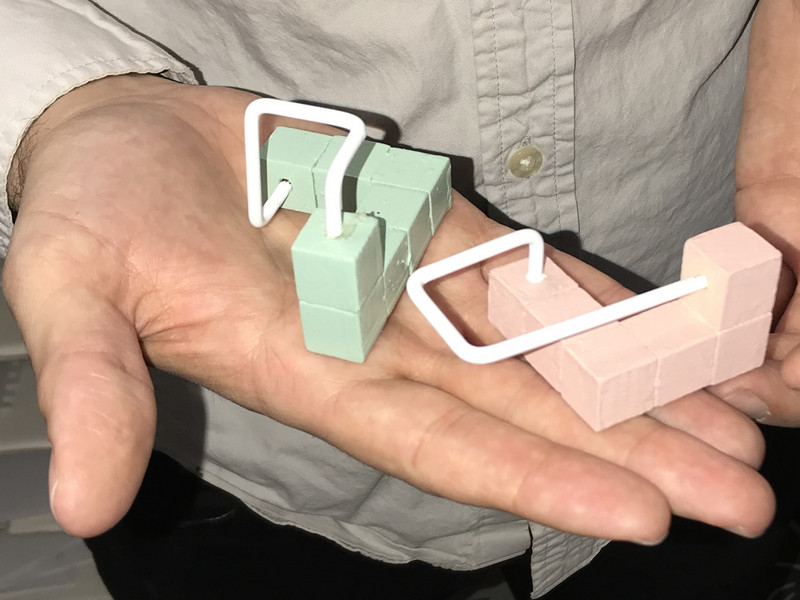

Each body of work has its own specific needs, and material choices are made based on those needs. Prior to this show, I had been working primarily with brass, bronze and copper, and anything that went on those paintings had to be made of the same materials, and the forms had to be suitable to those materials.

For Doubles, there are two works made from cast sterling silver, which was something new for me. The works are modeled after clay slabs I use in my studio, and I really wanted the small fingerprints and texture of the clay to register, and sterling silver is great at capturing this detail.

The works where linen or canvas begins as the basis for the painting, those works share the same straightforward, thousand-year-old sculptural process as the metal works. The cloth is not cloth, but painted polyurethane, so there is this added step of painting which is critical, where even the staples on the cast need to be painted silver. But I guess all of those ancient Greek and Roman statues were once upon a time painted too. I generally don’t enjoy the actual process of anything I make, in whichever material, but I also don’t come to the studio looking to enjoy myself. I let the ideas tell me how I should work in whichever material.

Can you speak to your beginnings as a sculptural artist?

I came to sculpture after a lot of painting and drawing, and also film and video. In art school, the sculpture department seemed to have so few constraints—you could make anything, you could make a painting or a video if you wanted. This was not the status of the other departments. So I went there to be free, in a sense. But eventually, I felt like I needed some of those constraints, and a rectangle on the wall—a painting—certainly offered that. I took the sculpture there.

What do you want to evoke within your viewers when they come to view the exhibition?

I’m not sure I can answer that. The show provides something like the raw materials for an experience. There is a particular density to the show, so there are a lot of possibilities when you visit, and the viewer can find something they need, something they might not get elsewhere.

Can you tell us a little bit about the book (Virus, Imposter, Infiltrator: Recent work by Maximilian Schubert, with a visitation by Felix Gonzalez-Torres) that is being published in conjunction with the show? How did that come about?

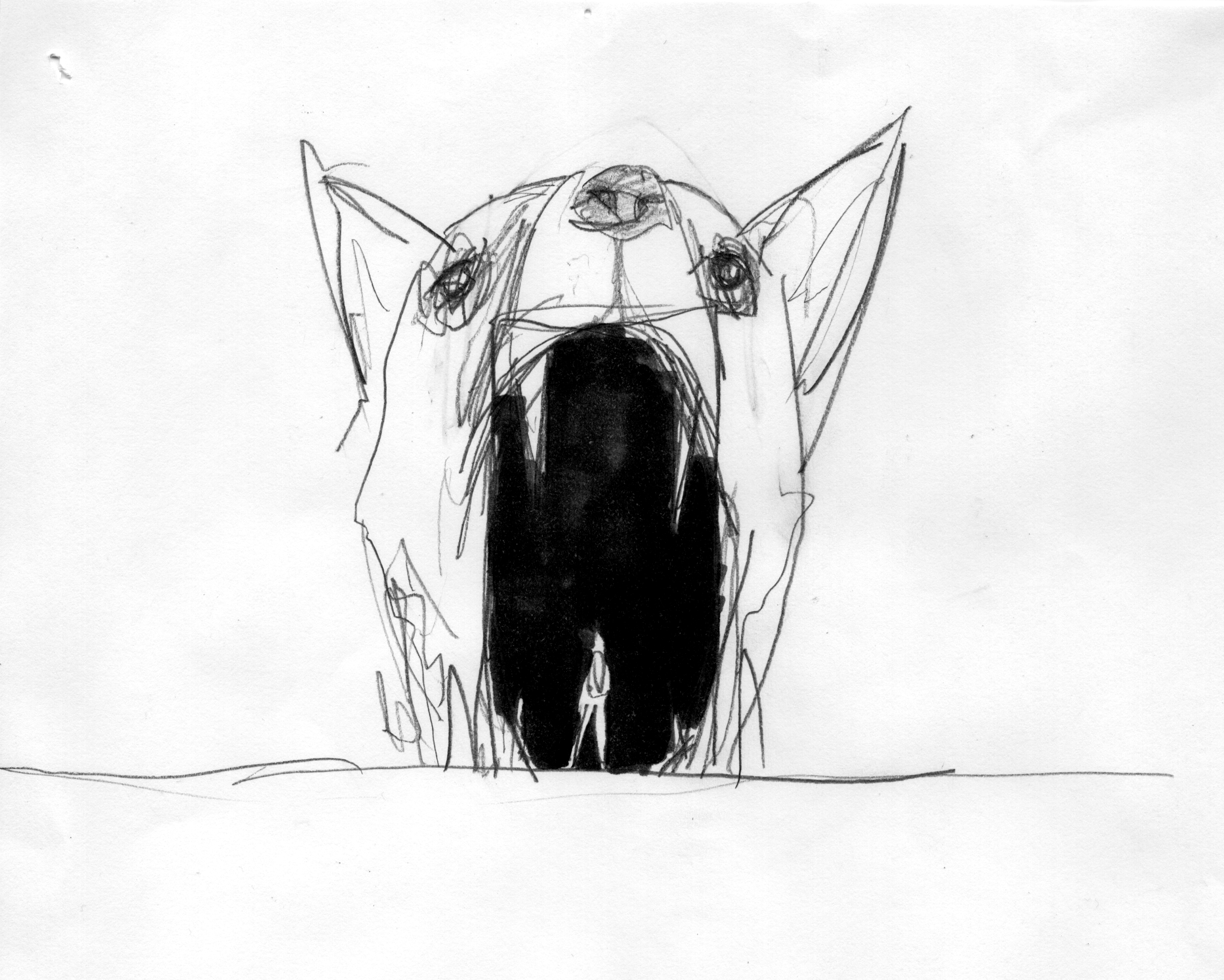

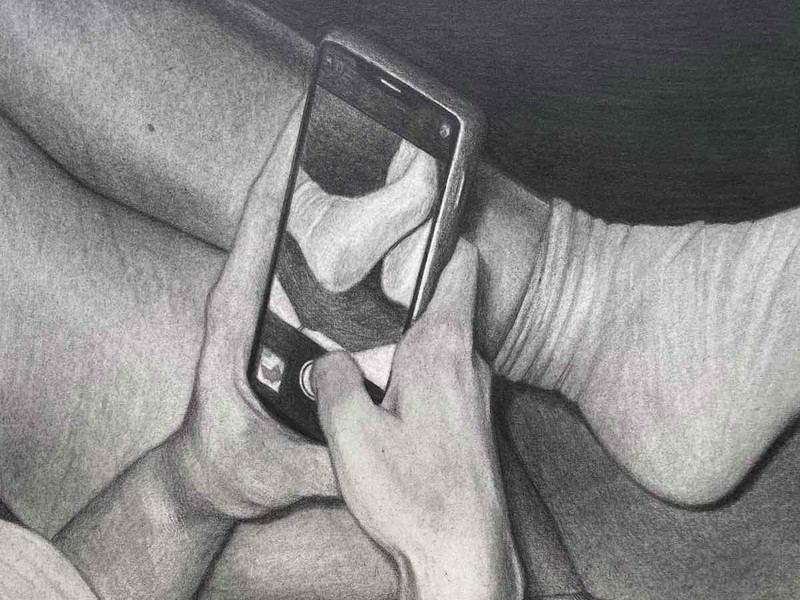

The book came out of discussions with Natacha Polaert, the founder of Off Paradise. I had mentioned I was thinking of making a book about the experience of making a show. I had a particular approach that I wanted—the quality of film was important, what you wouldn't see was important—and we worked through the ideas and brought the photographer, Kevin Brady, onto the project. After shooting a bit, we brought the images to Hassla, who agreed to publish it. Then the Felix Gonzalez-Torres work came into the picture, and Randy Kennedy was up for doing the essay. So you have this idea of doing something special, and then other people come into the picture and make it better than you could have imagined, and the result is really beautiful.

You stated that the book and exhibition are perhaps one of the most collaborative efforts you have ever been a part of. When you began this project, did you have any intentions of bringing such a deep level of collaboration into it?

A show always requires some level of real collaboration, but it really depends on the personalities involved. I’m fine working on a project alone, and then delivering on the deadline. However, this show, and with the book, I talked more about art with more people than I have for any other project. Collaborating on something, especially with several people, you really just feel your way through it, and hopefully it's natural and goes smoothly. Then there was the presence of the Felix Gonzalez-Torres work, and the idea that there is a whole art history with you in the studio when you make things, that you are always collaborating with whether or not you’re aware of it in the moment. Even with the doors shut and the blinds drawn, you can never say you’re ever really on your own in there.