"NOTES FOR A POEM ON THE THIRD WORLD (CHAPTER ONE)," 2018

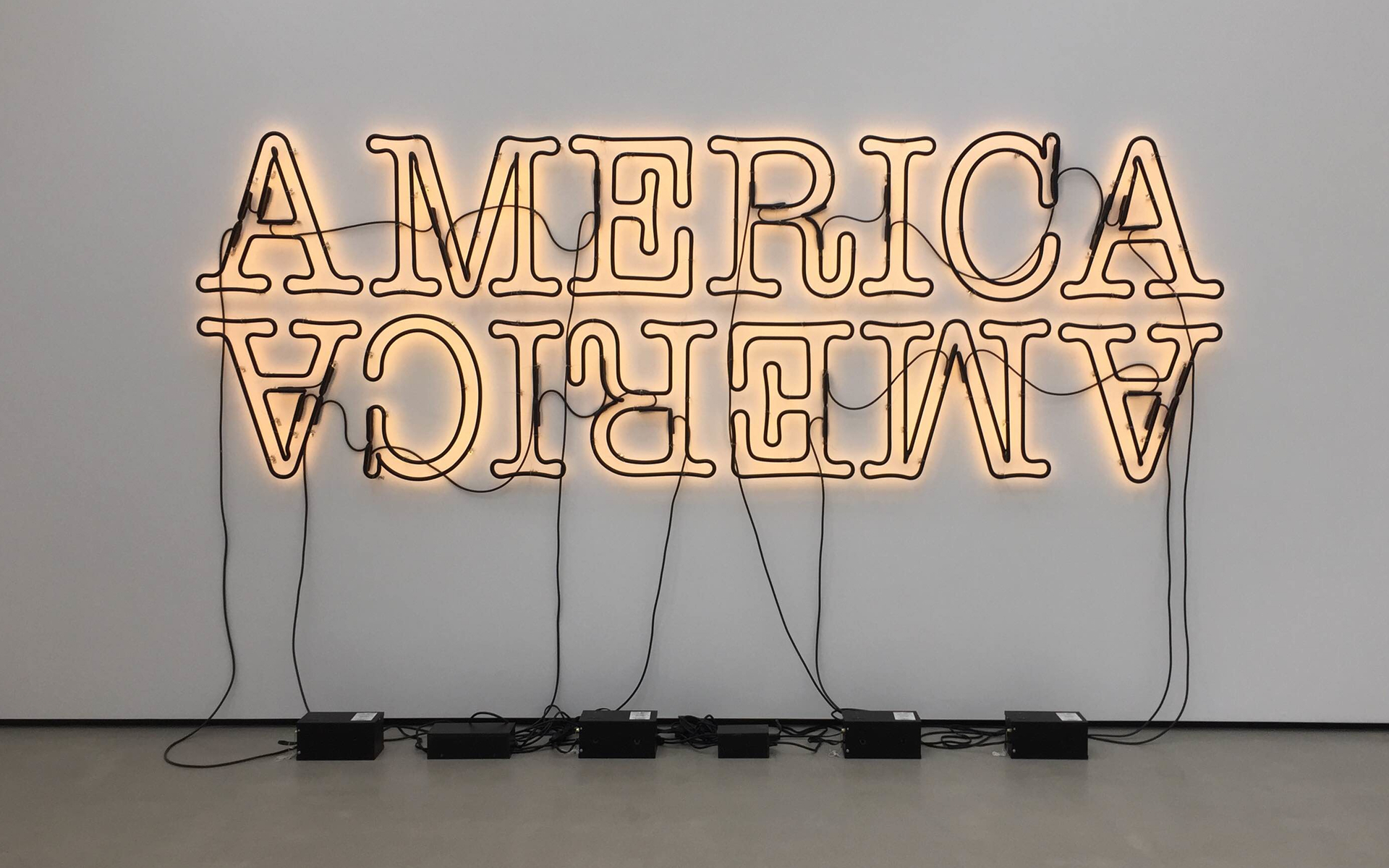

Like most artists, I started out hoping I would have something to “say.” Something spinal enough to make your eyes widen as your neck snaps back from the page. Squirmy enough to make your feet creep inward and pigeon-toed under the table. While in the process of finding my voice, I realized I had become a messenger for someone else, an intravenous therapy administering the claims for some cause or another, writing to tell the stories of those in need as opposed to needing to share something about myself. The work of Black artists is often the work of service to Black stories, as is the case for Glenn Ligon; Our wretched history, discriminating pain, our God rearing hope. As artists and Black men in White America, Ligon and I also share the disorder of a double consciousness. We “stand-in” for our community, whenever we stand out, and we’re perceived as threats to be put down wherever we show up. In both circumstances, the stakes are highly charged, though in the latter the charges are routinely dropped.

"Notes for a Poem on the Third World (Chapter One)," 2018 on view at Regents Projects LA (2019), figures two giant neon hands raised at 84 x 155 inches, mounted on the back wall in the gallery’s second room. Ligon has applied a layer of black paint to the face of the neon tubes, which consequently throws a ‘shadow’ of escaped light back against the wall producing an outer glow. The large-scale sculpture is in fact a trace of Ligon’s actual hands. Their painterly, adolescent line calls up the act of tracing one’s hands as a child when learning how to draw. In this way, he offers no fingerprints to mark his DNA. No major or minor lines of the palm to determine his health, a path his life will take or the depths of his intelligence. No lifeline, headline or heartline for some esoteric palmistry zealot to speculate. What his hands lack in forensics they provide in language. They shout, anxiously, “HANDS UP, DON’T SHOOT!” and in their startled angst give shape to too many wretched bodies that have echoed through the hearts and minds of a vexed diaspora.

These hands are painted black, like me. Raised high against and swallowed up into a vacuum of whiteness, also like me. Like two mirrors set face-to-face to reveal a number of images in infinite, Ligon’s hands draft a domino line of reflections. In his hands I see my own, in my own I see the outstretched hands of a community.

TURBULENCE

"Notes for a Poem on the Third World" is Ligon’s first figurative neon sculpture. In offering this work as a figure, it embodies the formal readings of a painting. By way of analogy, Gregg Bordowitz states in his analysis of a text-based painting by Ligon, "Untitled (I Am a Man)," 1988, “The great challenge a painter must meet is to distill motion into a significant form so that the viewer may sense, feel, and anticipate all the possibilities of motion suggested by the formal elements of the painting. Through line, color, and composition, the artist creates a compelling sense of turbulence, strongly felt by the paintings viewers.” He goes on to describe how “turbulence” is experienced in a third space, a space of thinking and making connections, mediated by our existence before we encounter the work and our relationship to it and the world after we leave it behind.

Applying that logic to "Notes for a Poem on the Third World," my third space draws up the figure of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager who was shot and killed by a white Ferguson, Missouri police officer on August 9, 2014. That shooting mobilized a community into protest, transforming Brown’s show of surrender into a weapon of resistance and a national movement that rallied behind “HANDS UP, DON’T SHOOT.”

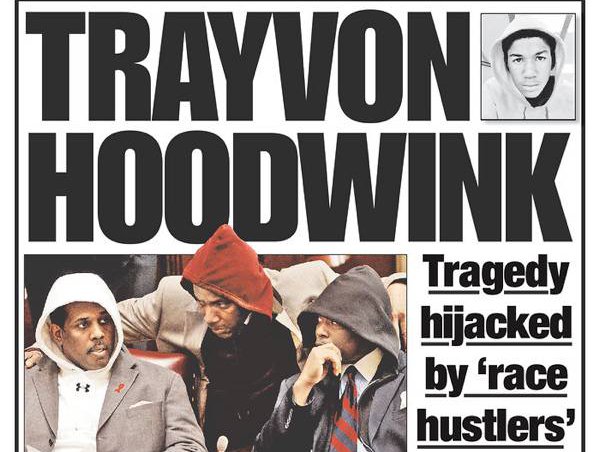

It reminds me of my dad Bill Perkins, then State Senator of New York. His signature fedora replaced by a hooded sweatshirt, flanked by Senator Kevin Parker and Eric Adams, who were also wearing hoodies as they walked into the senate chambers on March 26, 2012. They chose to wear hoodies on that day in solidarity for the family of Trayvon Martin, the 17-year-old who was shot in Florida for wearing “suspicious” clothing. Lampooned on the cover of the New York Post the next day, that photo is framed by text, scandalously, “TRAYVON HOODWINK. TRAGEDY HI-JACKED BY RACE HUSTLERS.”