Metamor-phases

Tell me about your show, In The Eyes of Each, at Faction Art Projects.

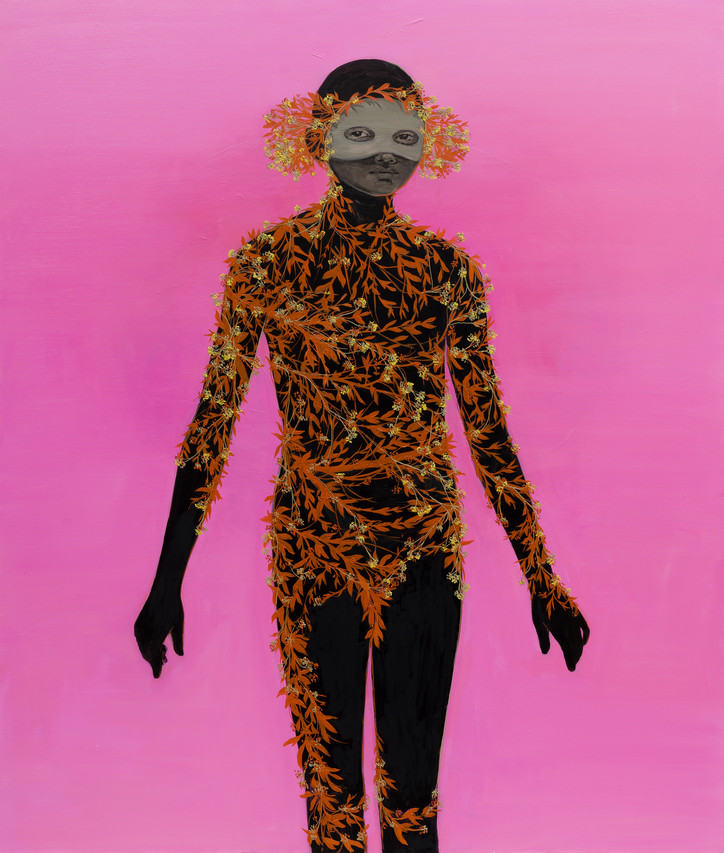

I’m super excited about this forthcoming exhibition because it’s the first big solo show I’ve had in New York and it’s great working with Faction Art Projects—from what I can tell it’s a fantastic space. I’ve been working on a series of paintings for the last two years to prepare this body of work for this exhibition. The work is a connected series of paintings which continue a theme that’s been present in my work for many years, it’s developing that fervor, and talking more about figures that are caught in a transition of self-knowledge and understanding and innocence—they’re transitioning from childhood to adulthood. That’s the overarching theme that’s been embedded in the work for some time, in this particular series of paintings, which is called In the Eyes of Each, it really does begin to explore those themes in connection with nature as well. So, they’re kind of protectors of nature. Each figure has nature within it and scribed across their bodies and through their bodies—they are kind of vessels, containers for nature. They’re acting as sort of time capsules—they have that sense of time held within them.

They’re almost like little goddesses or nymphs.

That’s really interesting that you respond to them in that way because actually, as part of my research—this is connected to historical painting and other historical research—and one of the key elements that I researched was the Apollo and Daphne story.

Is that the one where she turns into a tree?

Exactly! So, the arrows are shot by Eros, and the golden arrow goes to Apollo and that leaves him eternally in love with Daphne, who in turn has been shot by a leaden arrow, which means she’ll never reciprocate that love and because of that she tries to escape him. With her father’s help—she pleads with her father because she cannot escape Apollo’s pursuit—he turns her into a laurel tree, and so forever she remains in that state, she’s forever untouched. I thought that was an extraordinary connection with what I was researching, which is about that transition, about that discovery in oneself and the connection with others, and those formative connections with exploring others at that pivotal point in puberty. So, it really resonated with me in terms of that theme, and visually it was quite extraordinary, because in a lot of visual representations of Apollo and Daphne she has tree roots growing out of her, and branches for arms, and so on.

I love that they have Mickey Mouse ears—they’re almost like animals, too.

That’s quite interesting—I don’t see them that way, those forms for me are kind of an evolution of different references. The mask element, for example, has come through a lot of past paintings where I reference Venetian historical painting, so the idea of hiding or concealing one’s identity, which again resonated with the idea of finding an identity as you’re transitioning from childhood to adulthood—it’s about finding an identity but also about being like your peers, and not wanting to appear different, having that tribal connection. But also, those Venetian masks I’m referencing, the Moretto masks, are held in place by a button or a bead in the mouth. So, if you wore a mask like that, you were rendered speechless—so, this idea of non-communication I found really interesting. The masks and the headdress shapes evolved through drawings and research and references, all sorts of things, Velasquez paintings with those extraordinary shaped wigs and headdresses, and also more contemporary references, like the way young people wear their hair these days, the bumped hair at the side—they almost have that same beautiful silhouette of shapes that I’ve seen in historical paintings.

I think of the modern mask being a presence online—a social media account is a kind of mask. Teenagers are always performing for each other, and in your pictures, it seems like they’re retreating into themselves.

And I think there’s that sense of protection. So, a lot of the aesthetic qualities I’ve used, the decorative qualities, the embellishments, are almost a kind of armor, a sort of protection, maybe a cocoon or something similar.

Do you interact with teenagers a lot?

Well, I’ve had two of my own! So, in a very indirect way, my creative journey has been informed by my personal journey through motherhood, really, and having those connections with both my own children and their friends and peers, and just observing those different stages and how fascinating it is to be up close to that—seeing your own children transition, and the whole breadth of that as a stage in one’s life. We’ve all been there, as adults we connect with that, both for ourselves, and seeing it with others around. And to a greater or lesser degree, people have trickier times than others, but however we’ve navigated that transition, there are always key, pivotal moments that are difficult for us all—and this is what I’m trying to tap into. But also, there’s this sense of wonder and beauty, the youthful element, the innocence of that.

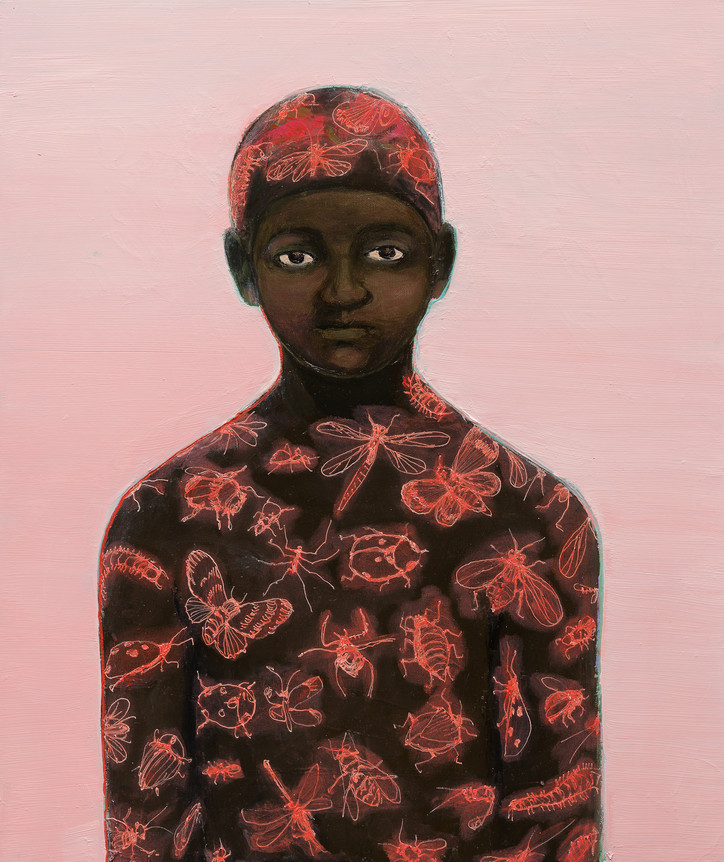

Above: 'Luminous' and 'Golden Arrow.'

It’s such a universal theme. Why do you think we’re drawn to that time, even as adults, because it’s always a subject in film, art, etc. What is it about that time that's so fascinating for us?

It’s very hard to pin it down, but I think it’s because so much happens at that point, you’re at a particular peak, both in terms of your physical manifestation, and very often it’s about the sexual awakening or the innocence—there’s that tipping point between innocence and awareness. I find that really fascinating, that pivotal point. Also, there’s almost an oversensitivity about that as well, we’ve all become hyper-aware of these different stages of puberty—maybe there’s even too much focus on it at one point.

I didn’t even think of the sexual aspect—do you feel there’s a certain sexuality to the paintings?

No, I don’t. They’re more innocent in that regard—they invite the viewer to to reconnect with that innocence, and maybe to reconnect with something simpler, to be at one with things, with nature, in a less complicated way.

So, it’s like they’re not entirely physical.

They’re sort of poised, as well—they’re very still and quiet in their moment.

I love that they’re connected to historical paintings, as well—I feel like people forget about historical painting in their crazy pursuit of weirdness in the art world.

My whole artistic practice is very connected to historical imagery—it’s always been a really important part of the development of my visual language. I think when you’re going through early stages of your creative journey, historical painting is a really important reference—it’s really important to understand what you’re connected to and how your visual language develops from that. For me, that’s key. As a figurative painter, that’s a very important element, this connection to historical imagery—painting and sculpture, as well. It informs the work.

What do you think makes something that references historical painting 'modern?' What pulls it into today?

I suppose it’s not such a literal thing, it’s just so embedded in my practice that those connections and references are very subtle, but if you looked at a Velasquez painting or Rembrandt or Vermeer—Vermeer is one of the painters I constantly revisit. There’s a stillness in a Vermeer painting that I’ve always emotionally connected with, and that’s something that I’ve taken from Vermeer, that sort of caught moment that is quite extraordinary—I’ve held onto that emotional connection that I get from his paintings, and it’s something that subconsciously enters the work. Velasquez has a sense of drama and draftsmanship and real impact—I’ve always wanted that sense of drama, but also color. Color is very important for me—that sort of playfulness with color, those odd combinations of color that bring the work through in an interesting way.

When you say Vermeer, it’s almost like they’re voyeuristic, or caught off-guard.

There’s less that sense of Vermeer and more the sense of being in that same space as that figure—that you’re actually transported to that moment in time and you’re sharing that moment with that figure. It’s like a frozen moment. Even though they’re very small paintings, the space opens up to you, and you are engaging with those paintings, and the physical barrier of paint dissolves and you are there, looking at it in great detail. The detail in Vermeer is like witchcraft—painterly witchcraft.

'In the Eyes of Each' is on view at Faction Art Projects from November 1 through November 25.

Lead image: 'Song of Starlings;' all images courtesy of Faction Art Projects.