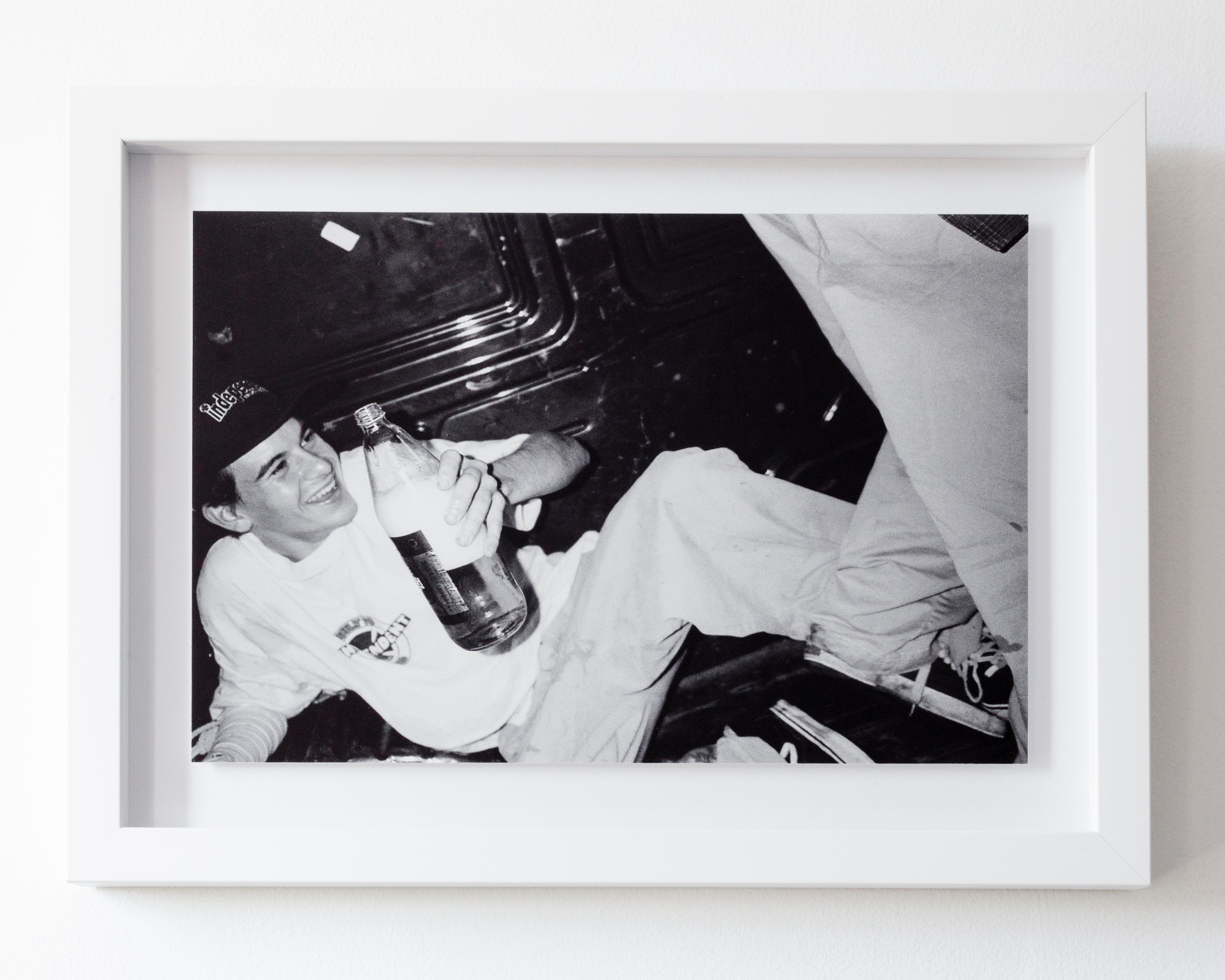

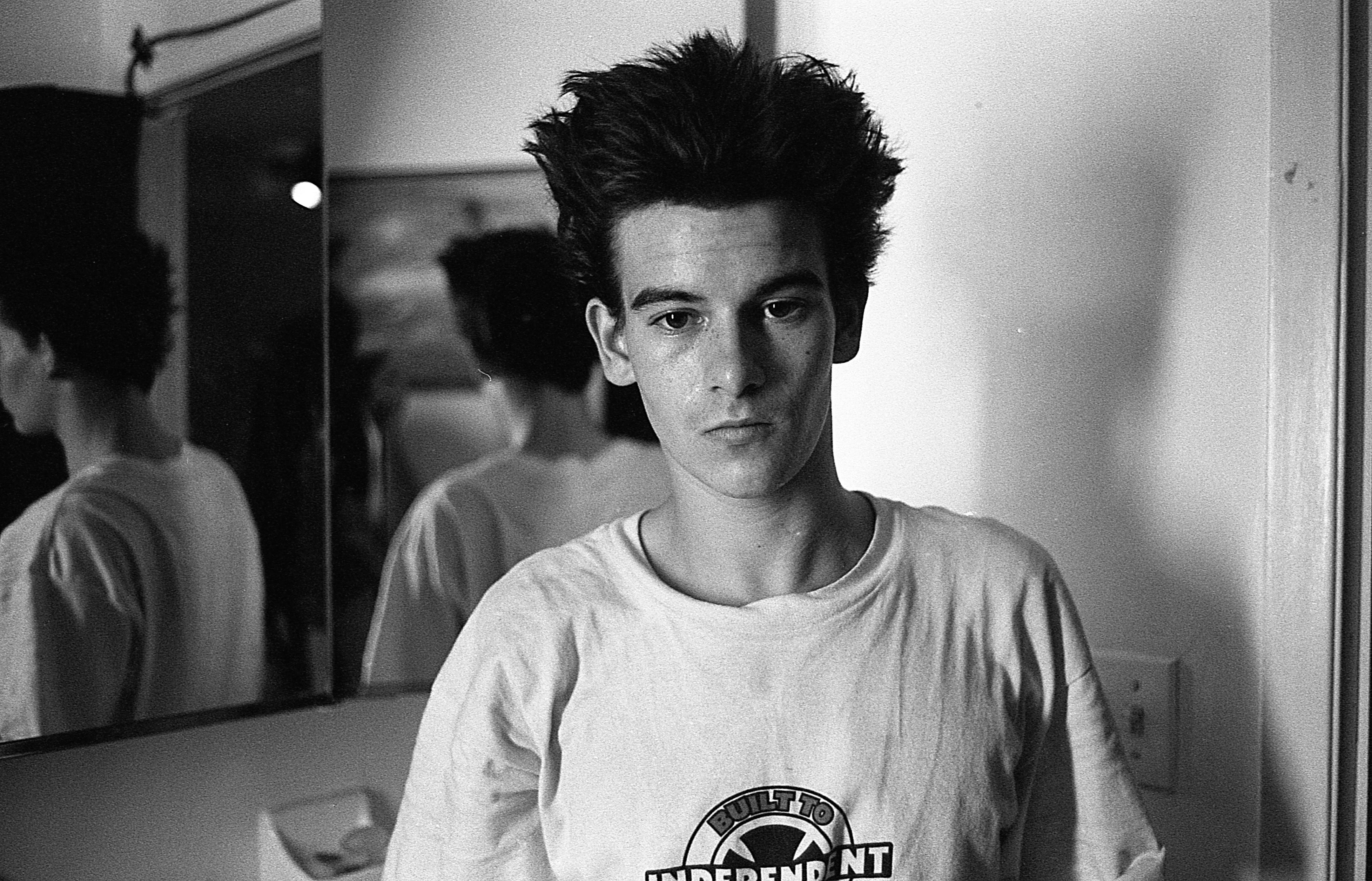

There’s this intimacy you get with design. I can tell you the width and thickness of the handrail at City Hall in Philadelphia. I can tell you what the granite on the ledges of Love Park felt like. I can recall the color, texture, the height and the seam on the granite, the rhythm of the bricks under your feet, all that. You just register all this on a subconscious level before you even know what the word “design” is. I had no idea what architecture and design were when I was growing up. Nobody told me.

It’s a more intimate knowledge, actually being on the surface and trying to figure out how to maneuver it.

It’s so much more intimate because you’re on it. Especially for me, growing up in a city like Boston, you’re on it winter, spring, summer, fall. I know what the temperature of that ledge is in August vs. January. I don’t know that there’s another way to get to know architecture as well. It’s the things that humans touch — not the fiftieth floor, but the ground floor. I don’t think there’s a better way to study architecture than skating. It’s the art of crafting the human experience with space. All the best skate spots are the result of great spatial thought.

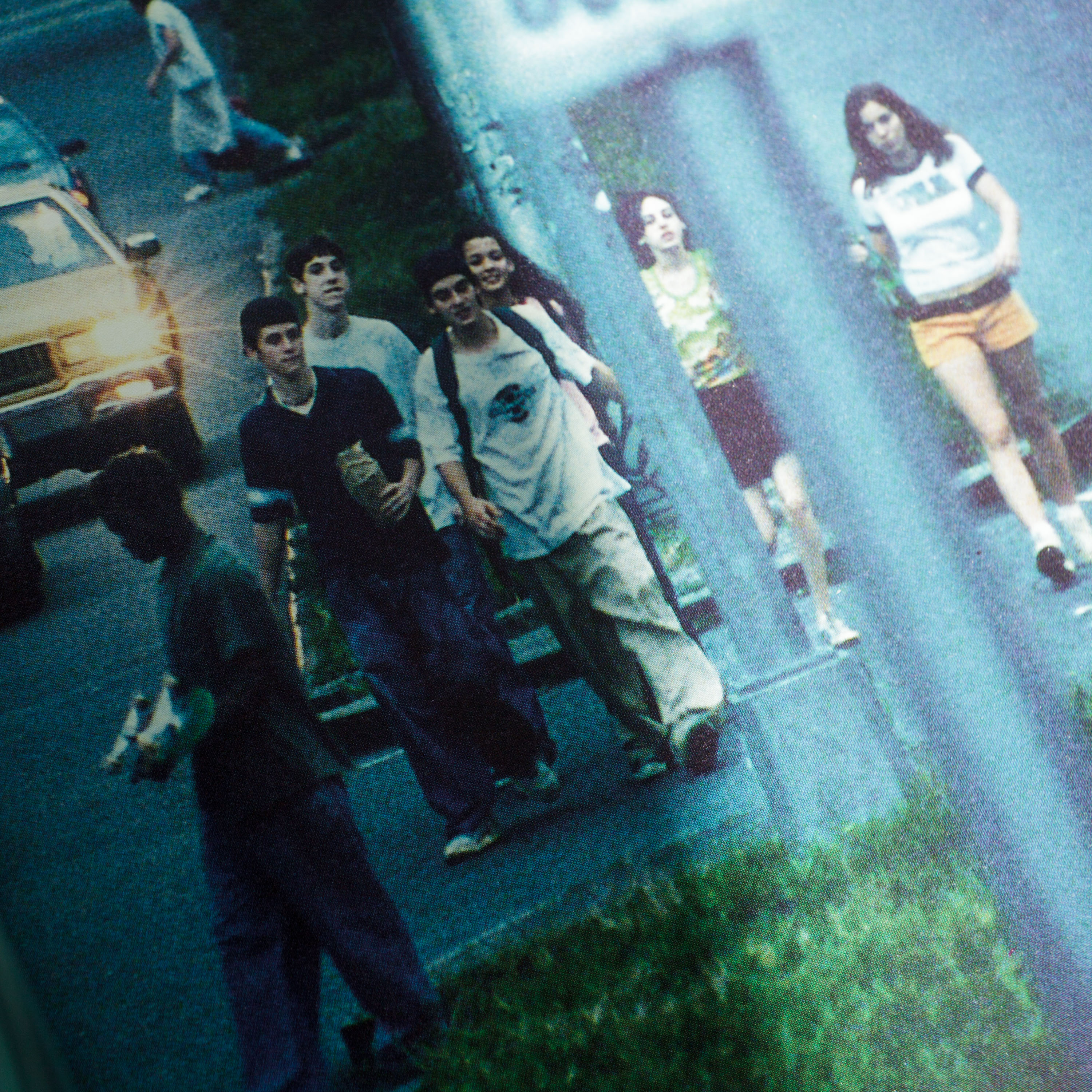

Lawrence Halprin, who designed Embarcadero, his wife Anna Halprin was a choreographer — she’s amazing. They talked about architecture as choreography, and they would do these choreographed schedules: 8am have your coffee and sit on the bench, 9am walk into the building, etc. They would choreograph their spaces. And I think he might’ve been fascinated with the way that Embarcadero became a hotbed for street skating in the 90s, and was really the petri dish where the culture grew. The architect of Love Park, the architect of Brooklyn Banks, these guys are part of that second wave modernism — they’re the people who would’ve studied under Louis Kahn– that’s the way that the plazas in streetskating were born. They kind of go hand in hand.

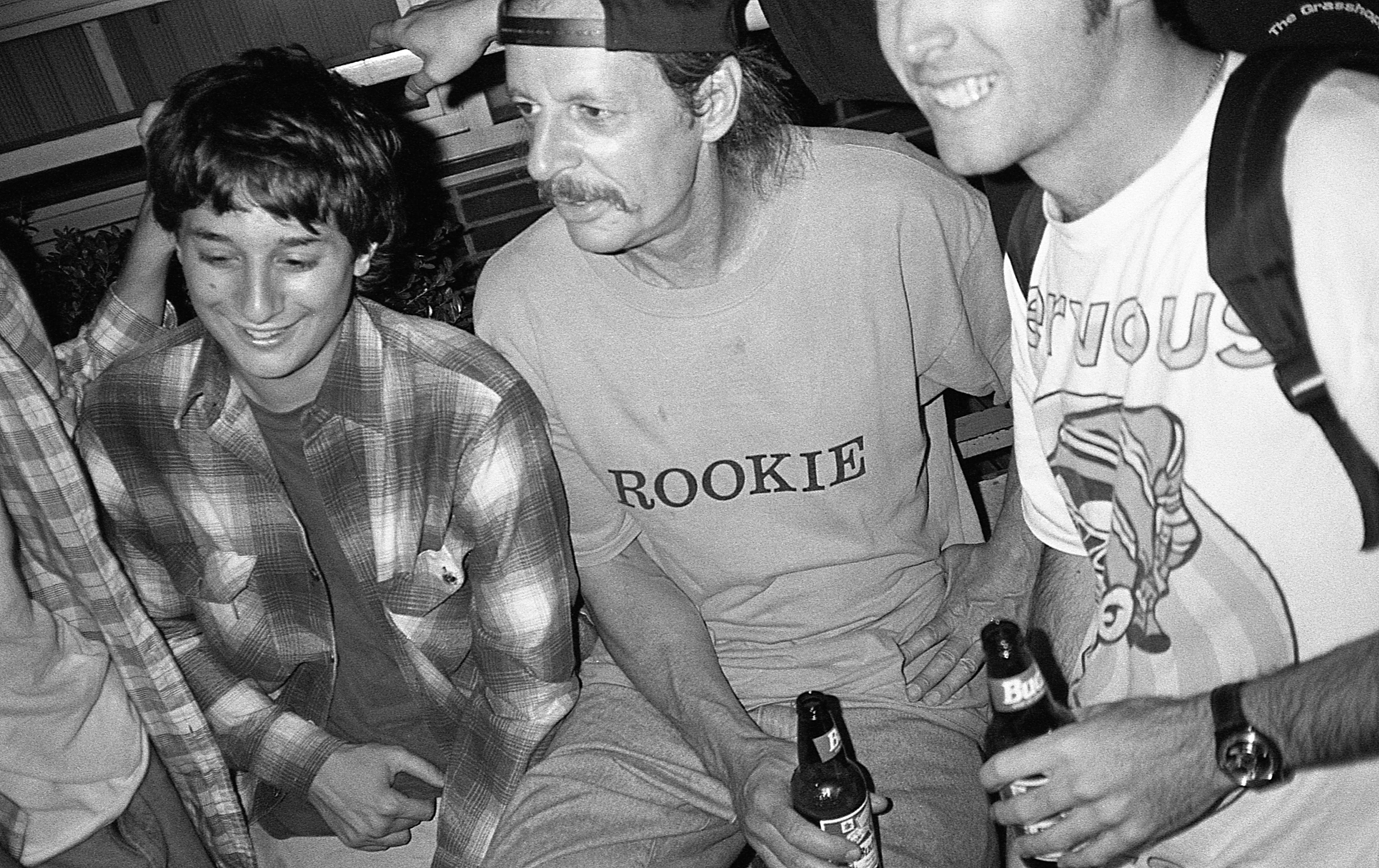

Which is interesting because not a lot of people consider skateboarding in relation to art, to architecture, to design — maybe not until very recently. Because, you know, there’s a history of delinquency being attached to skateboarding, which is true to an extent, but people don’t see the intention and the art behind it — that it’s more than going and trashing some place.

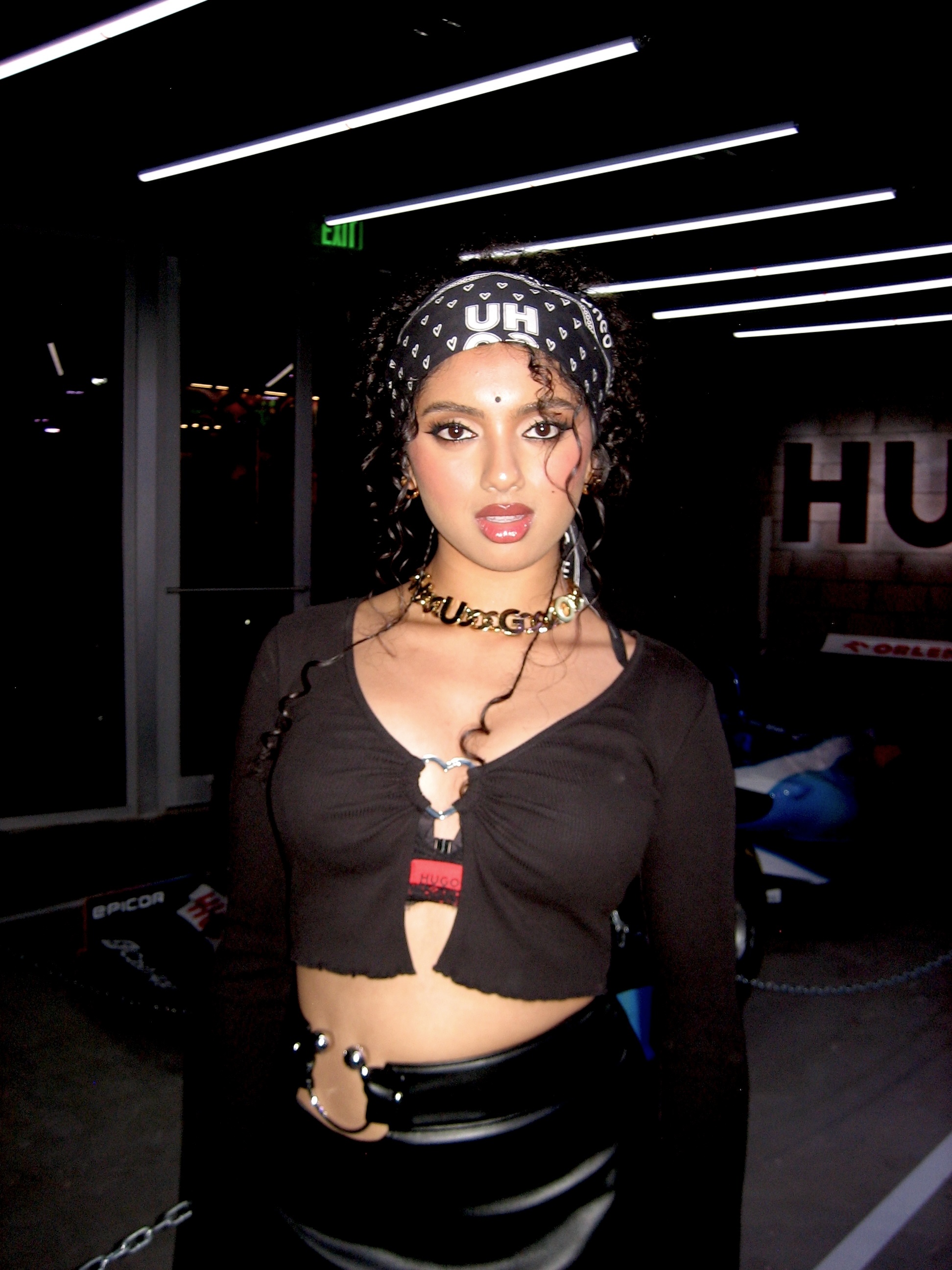

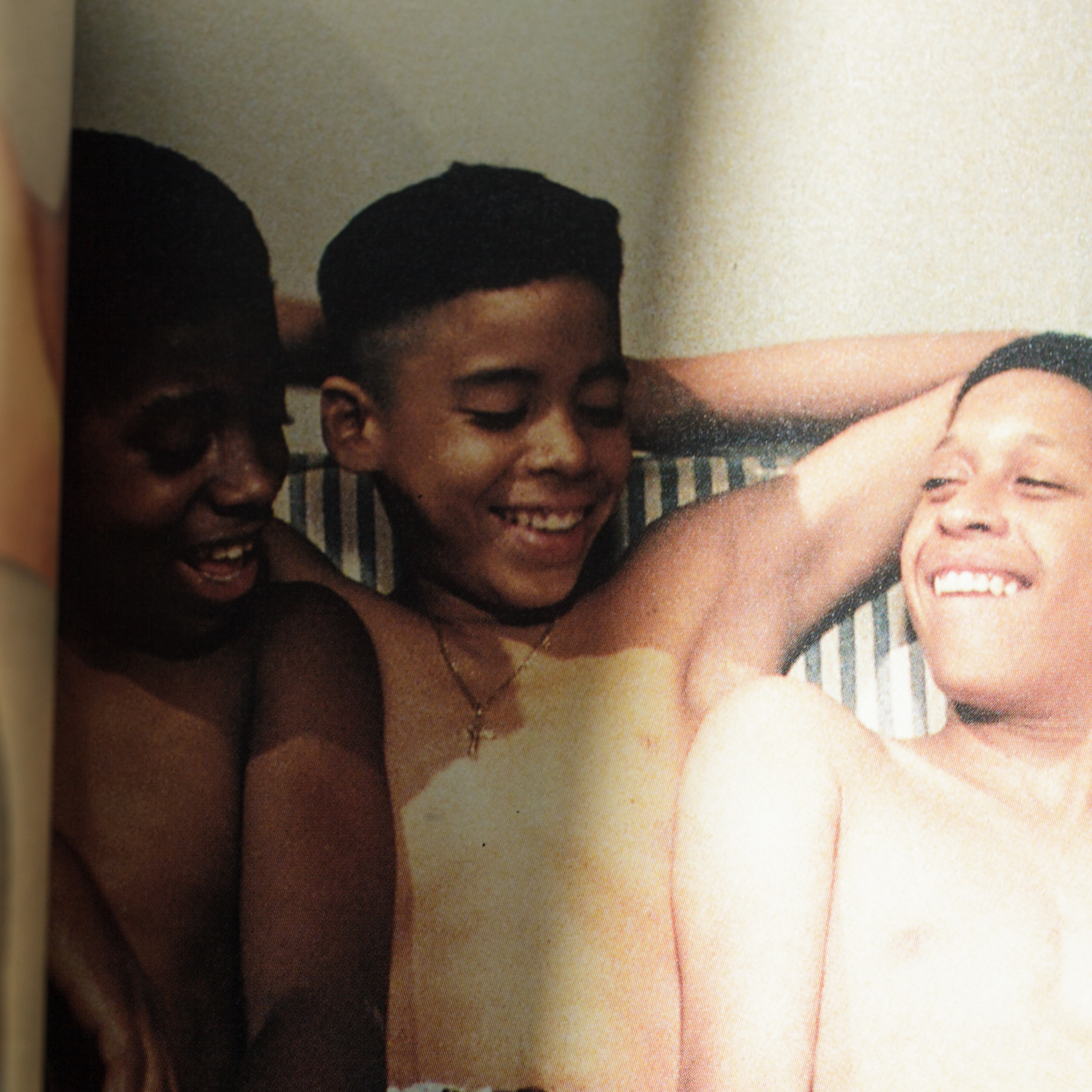

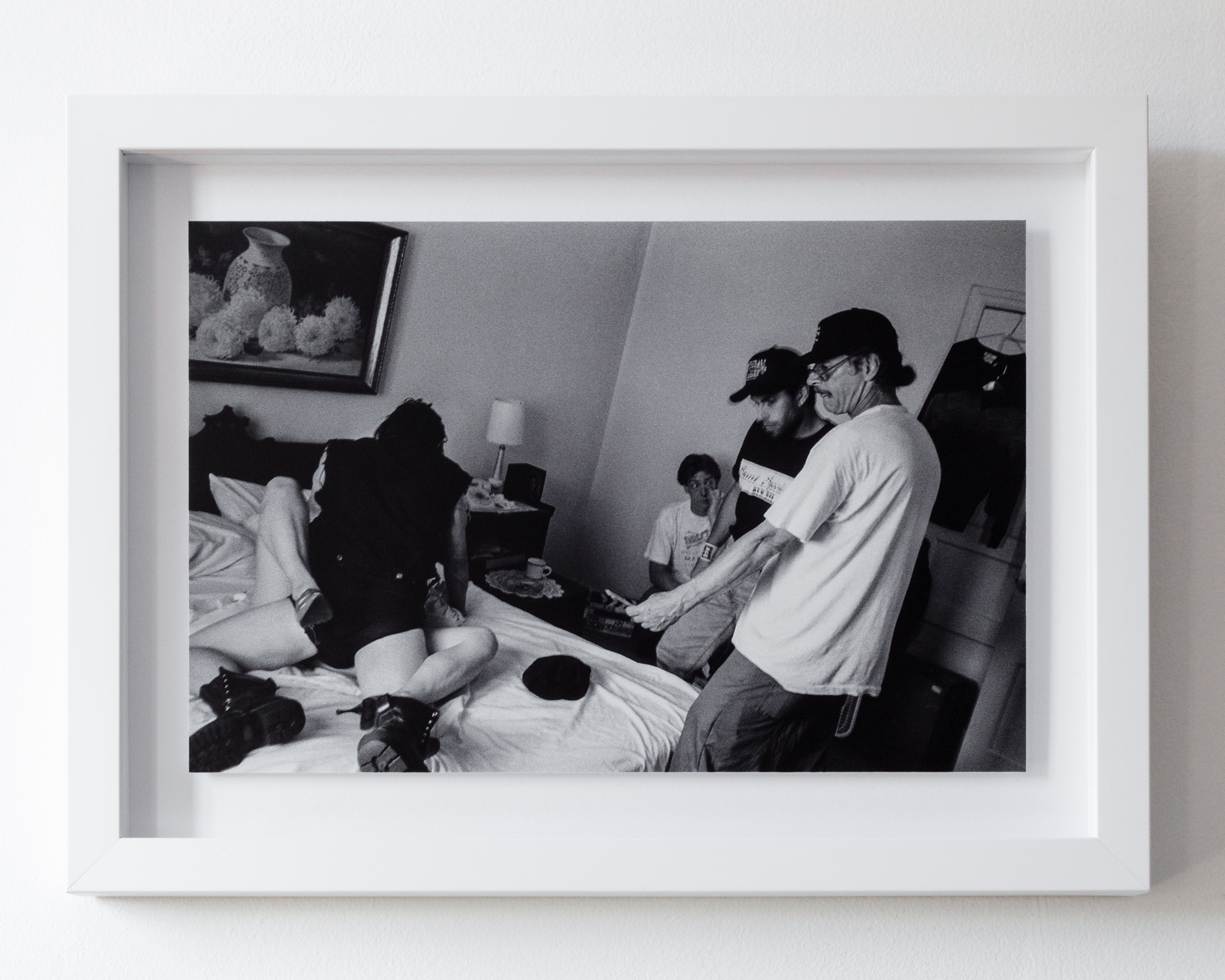

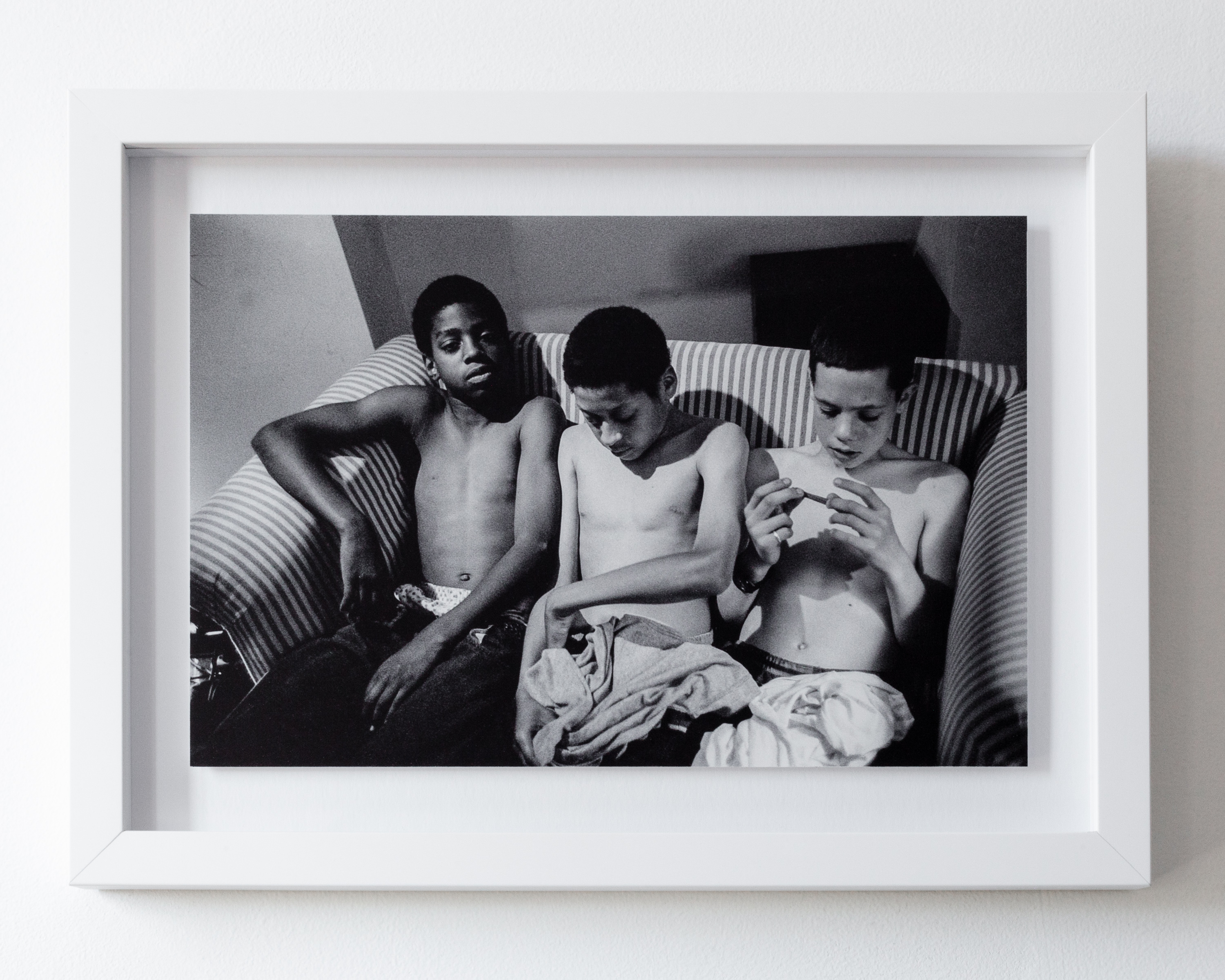

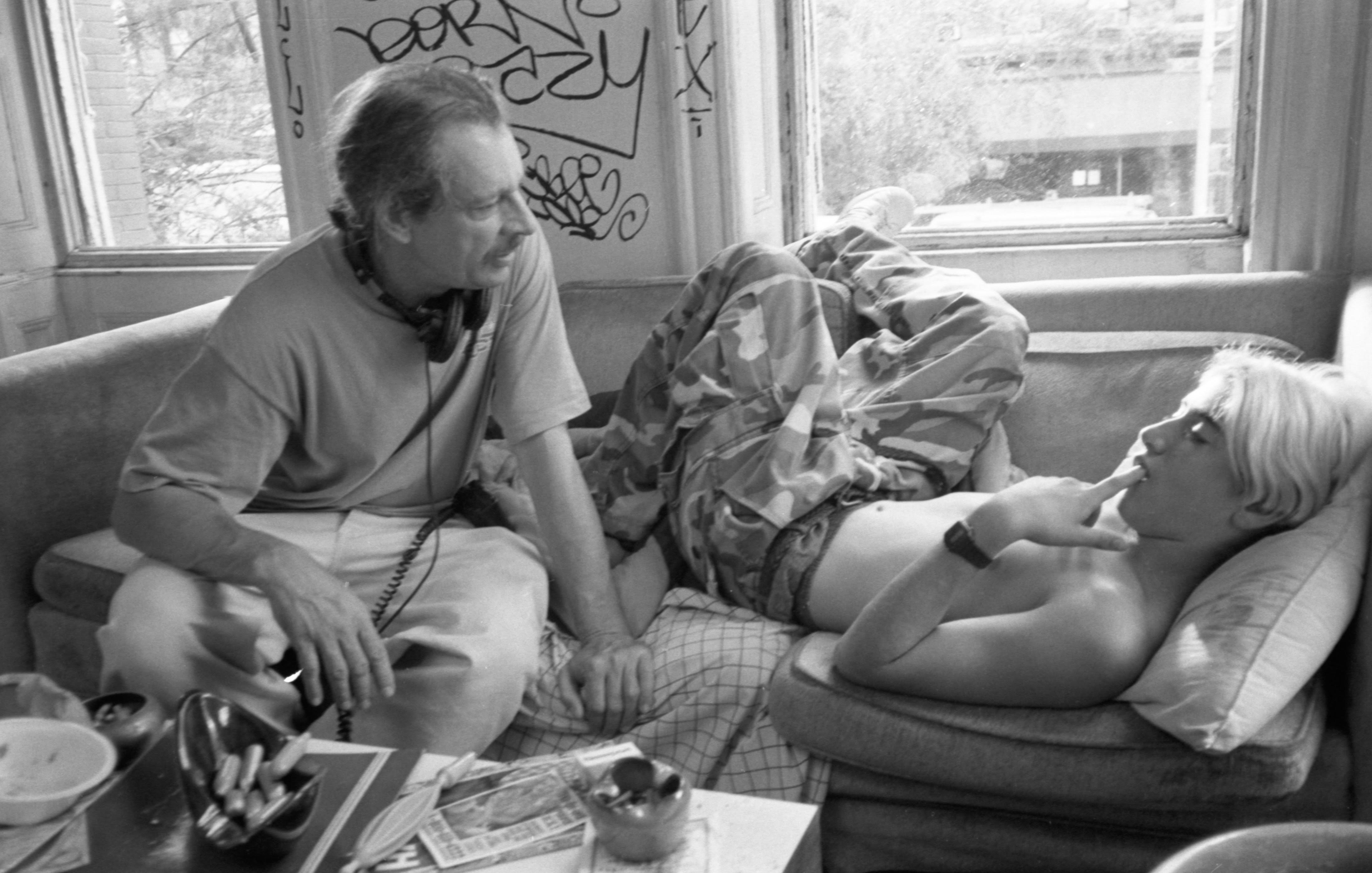

I think it’s hard for people from the outside who don’t understand — they just hear the noise and they see the damage. But they don’t realize the shelter that skateboarding has created for people, the inclusivity of skateboarding, the education that’s happening in skateboarding, the mentorship that’s happening in skateboarding — it’s a profoundly positive impact on society. When I grew up, the general public did not see that at all. Cops take your board and give you a ticket. At Prudential Center in Boston, there was someone up on the tenth floor who would pour water on us from above. One time a guy intentionally drove into a skateboarder, and then a bunch of skaters came out and smashed his windows with their boards. It can go the wrong way, but it really should be celebrated and embraced. And now it is in many cities — most cities have safe places to skate.

To that point, pretty recently in the history of skateboarding are we seeing a move from the fringe to the center — skateboarding is in the Olympics now, it’s getting legitimized in a way it hasn’t been before. What do you think of that?

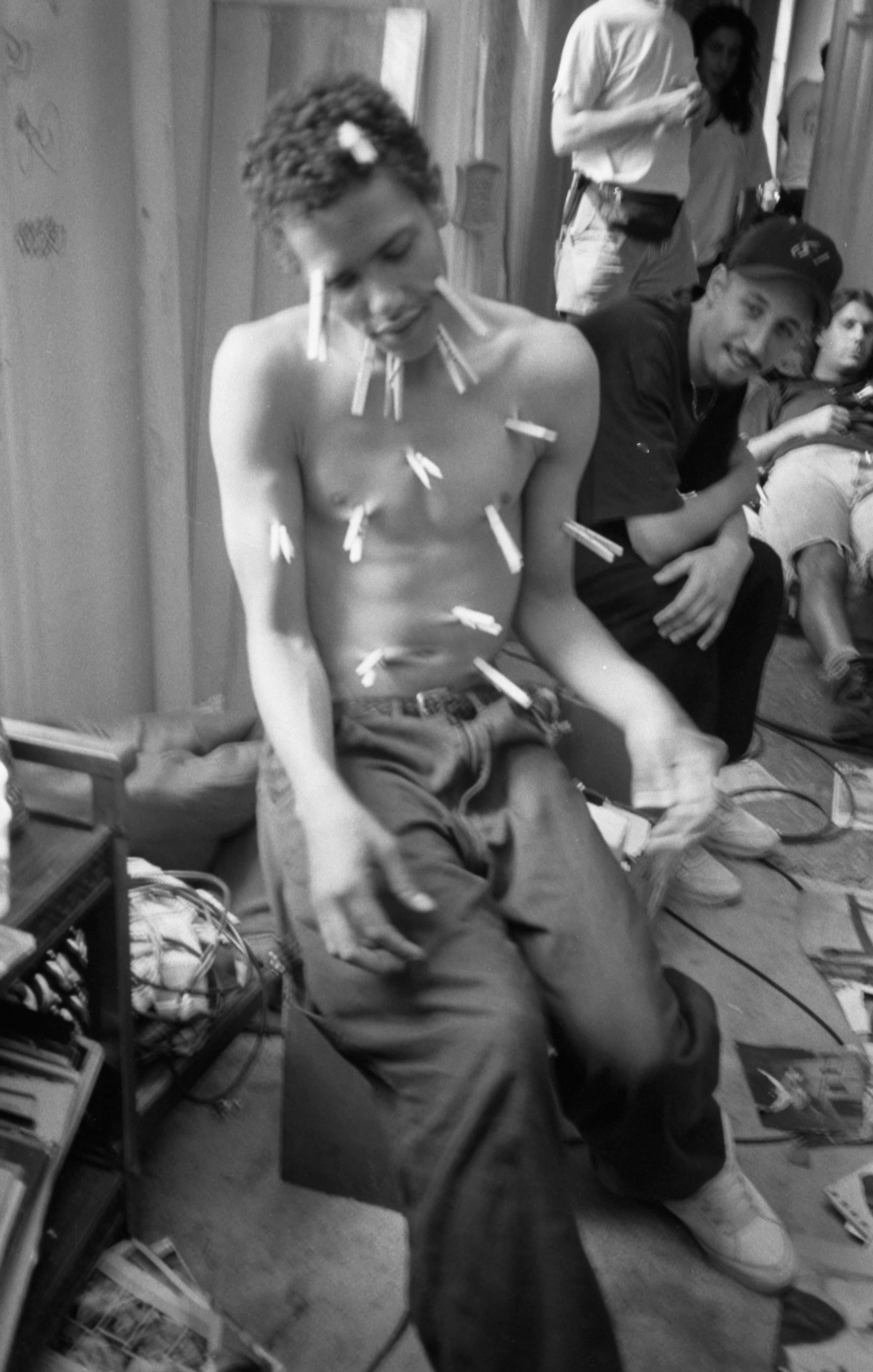

What’s great is that skateboarding continues to have subcultures. So this move into mainstream — that’s a move for some people, but not for everyone. Skating moved into the mainstream in the late 80s and created a caricature of itself, a cliche of itself — we had Gleaming the Cube. But then it pulled back and skaters went underground again. There’s always gonna be a die-hard skater-for-skater culture and economy — and that’s where it touches so many more people. And that’s good too.

Which isn’t to say that cops aren’t still going to try and kick you out of places [laughs] But it’s a bit of a double edged sword, because yes you have more people getting invited to the sport, but then you give corporations more opportunities to captialize off of and exploit the culture.

Skating gets exploited a lot. It’s an 80 billion dollar global industry, so to become that size means there's a lot of exploitation of labor, of identity– there's a lot of theft going on. But in the end, what are the benefits? The more people skating means that more of the most talented people — who might’ve otherwise been cross country runners — discover skating and then push the limits of what skateboarding can do. That’s the number one benefit. The more people who skate, the more supertalents emerge, the more cultures adopt skateboarding.

I think of globalism as total bullshit — go to McDonalds in Paris and the waiters take themselves very seriously and you can get a burger on a baguette. Go to Milan and it takes them half an hour to get you a burger and it’s not even fast food anymore. Go to Antwerp and they have that whole initiative where McDonalds is all run by handicap people and it’s this real socially conscious place. And then hit the McDonalds drive through on the 101 freeway, and it’s a different thing all together. So, as cultures adopt skateboarding, you get a different take on it.