Miu Miu M/Marbles

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

Wet Dreams follows up on the 2022 edition of Mayrit, The Drowned Worlds, evidently appropriate themes for a biennial that takes its title from the 9th century name for Madrid which translates to “place of many waterways”. Unlike many biennials, which work to distinguish themselves thematically from their predecessors, Otero Verzier opted to build from the framework of the prior installment: a clever move that gestures to the priority of knowledge-building, social relation, and the biennial’s longer-term ambition to “position the Spanish capital as a creative focal point for emerging talent.”

Mayrit’s Curatorial Director, artist, and designer Joel Blanco, helps execute this vision. He notes that “the first edition was mostly for ourselves, the less established designers from Madrid who just wanted to have fun by creating their own events. We are gradually reaching a wider audience without forgetting about the independent, less mainstream proposals. Our approach was to fertilize the creative ground here by helping creatives develop their practice without the constraints of profit.”

Mayrit, which often takes on the celebratory and social spirit of a festival, is anchored by two notably strong institutional exhibitions: Wet Dreams, the title show at Madrid’s Centro Centro art center curated by Otero Verzier, and Espejito Espejito (“Mirror Mirror”) curated by architecture collective Grandeza Studio at the Museo de América at the western edge of the city center. Other venues, like the Bate Social Store which houses the Bienal’s design shop—a curated storefront with design objects selected from an open call — and the National Museum of Decorative Arts, which hosts Materia Computada — an exhibition curated by HyperStudio — atomize Mayrit’s itinerary across the city. “Mayrit has seeded many collaborations, and we are reaching places that were previously outside the scope of current design practice,” says Blanco.

Wet Dreams Deck Chair for Caliper's Editions Programme in collaboration with Mayrit Bienal. Designed by Miguel Leiro and Victor Clemente with Berit Levy and Caliper.

In Wet Dreams, Otero Verzier gathers an impressive array of work spanning film, industrial design, research, photography, and architecture, presenting contributions from peers, friends, allies, and a few students she has recently taught at the Design Academy Eindhoven. Artist collective La Cuarta Piel contributed documentation of their 2022 durational performance, “Spa Profundo,” in which they immersed performers in a hedonistic deluge of viscous marble extraction waste from a mine in the Vinalopó River valley near Alicante. A sample of their white mud pool inhabits the gallery in front of photos of limbs writhing in apparent delight: a visceral, if wry, critique of the slow violence of extractive capitalism. Models of Andres Jaque’s 2015 MoMA PS1 pavilion, the water-filtering “COSMO,” and the recent “Rambla Climate House,” designed with Miguel Mesa de Castillo, bring to the show an optimistic exuberance that points to architecture’s capacity to perform instrumentally at the scale of daily life. And in “Atlas de Plantas de Cuartos Oscuros en la Ciudad de Barcelona,” Pol Esteve Castelló presents floor plans of fifteen dark rooms in Barcelona with unlikely precision: sites of pleasure where social exchange often accompanies fluid exchange.

The show brings together a generation of new thinkers with urgent political and social preoccupations that reflect Madrid’s increasing centrality in design discourse. In recent years, Spanish designers have built an influential presence in American and European schools of architecture (Jaque, for instance, is the Dean of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Preservation, and Planning). Only a few years ago, both Leiro and Otero Verzier were both living abroad — Leiro in New York and Otero Verzier in The Netherlands—and recently have returned to Spain, setting up in Madrid. Grandeza Studio (Amaia Sánchez-Velasco, Jorge Valiente Oriol, and Gonzalo Valiente Oriol), curators of Espejito Espejito, work between Madrid and Sydney. They typify the far-reaching interest in the country’s creative vanguard, and the way it is gathering anew in the country’s capital, fostering conversations that expand beyond conventional discourse.

Video triptych for Espejito Espejito featuring 'Los Escombros' by La Escuela Nunca y los Otros Futuros, 'America Megabyte' by Nmenos1 and 'Sabe Dios' by Julia Irango and Jorge Nieto (with Ana Moure and Cesar Fuertes). Photo by Asier Rua.

Espejito Espejito develops from ideas articulated by Argentinian anthropologist Rita Segato, and from Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano’s argument that the very idea of Europe is predicated on the European “invention” (rather than discovery) of America, and its subsequent colonization. Grandeza Studio invites artists—many of them from Central and South America and their diaspora communities—whose work uses the notion of the mirror to “redirect its distorting power.” That this takes place in Madrid’s Museo de América, what the curators call a “historical guarantor and archival reservoir of the Eurocentric autofiction,” is noteworthy. The museum’s new director, Andrés Gutiérrez Usillos, was appointed in 2023 and has declared his ambition to decolonize its collection. Espejito Espejito is housed in a gallery that previously held an exhibition titled El Hombre (first installed in 1994), and vestiges of it remain in a savvy curatorial move that point to the discursive distance between old guard and new.

Some interventions from the show’s artists have further highlighted precisely this sort of friction. Earlier this year, Colombia’s Minister of Culture made a formal request to repatriate the Quimbaya artifacts—a part of the Museo’s collection—which has so far been declined by the Spanish government. Colombian artist Juan Covelli synthesized prospective new artifacts using a generative adversarial network (GAN) trained on images of the Quimbaya Treasure in an attempt at symbolic repatriation. Next to the vitrine housing Covelli’s work is a wall label authored by the Museo, clarifying that the participating artists’ views “do not necessarily represent the opinion of the institution,” and inviting visitors to see the actual relics on the building’s second floor.

“Espejito Espejito” includes vital contributions from Martine Gutierrez (“HIT MOVIE: Vol. 1”), Tatyana Zambrano and Hernán Rodriguez (“Banana Valley”), and Naomi Rincón Gallado (“Sangre Pesada”), organized in an improvised scenography composed of scaffolding and silver curtains devised by the show’s curators. The exhibition takes big risks that pay off. It is radical in the way that it works from within and alongside a museum grappling with its colonial legacy live, out in the open. Perhaps it is through dissident guest programming like this that the institution can advance beyond its own burdensome history. On a quiet day, I even observed the gallery docents playing “UNKRNS: Beyond the Entrepreneurial Spell,” a video game made by artists Diego Morera and Sebastián Lambert. Indeed, “Mayrit aspires to build more bridges with Spanish-speaking countries to give them a platform here as well,” says Blanco.

Tapiz, tapiz, 1.000 millones, please (2024) by Virginia Sosa Santos, Sebastián Lambert and Diego Morera & Banana Valley (2022) by Tatyana Zambrano and Hernán Rodríguez

Miguel Leiro, Mayrit’s Founder and Director, has cited La Movida Madrileña, the explosive creative scene of the 1980s that followed Francisco Franco’s death in 1975, as a reference for the milieu he’s interested in cultivating now. In that time, figures like Pedro Almodovar and Rossy da Palma emerged alongside new cultural dynamics and amidst a new openness around sex and glamour. Mayrit’s programming subtly nods to that moment every now and then. Its opening night party (co-organized by the local music incubator Los Invernaderos) was hosted at Sala El Sol, a venue where Almodovar and bands like Radio Futura would hang out and play. Leiro’s father, a sculptor who emerged from the same artistic movement as Marina Otero Verzier’s (who is a painter), would spend time there in the 1980s as well, descending its red spiral staircase as a new crowd did for Mayrit’s inauguration this spring. As this latest crop of young madrileños danced into the late hours of the night, sweat and drink perhaps conjured yet more novel visions of a cultural scene emerging anew. Evidently, currents still flow in Madrid’s underground.

Wet Dreams runs until August 25th at Centro Centro. Espejito Espejito runs until November 24th at the Museo de América. The full program for the 2024 Mayrit Bienal can be found at mayrit.org.

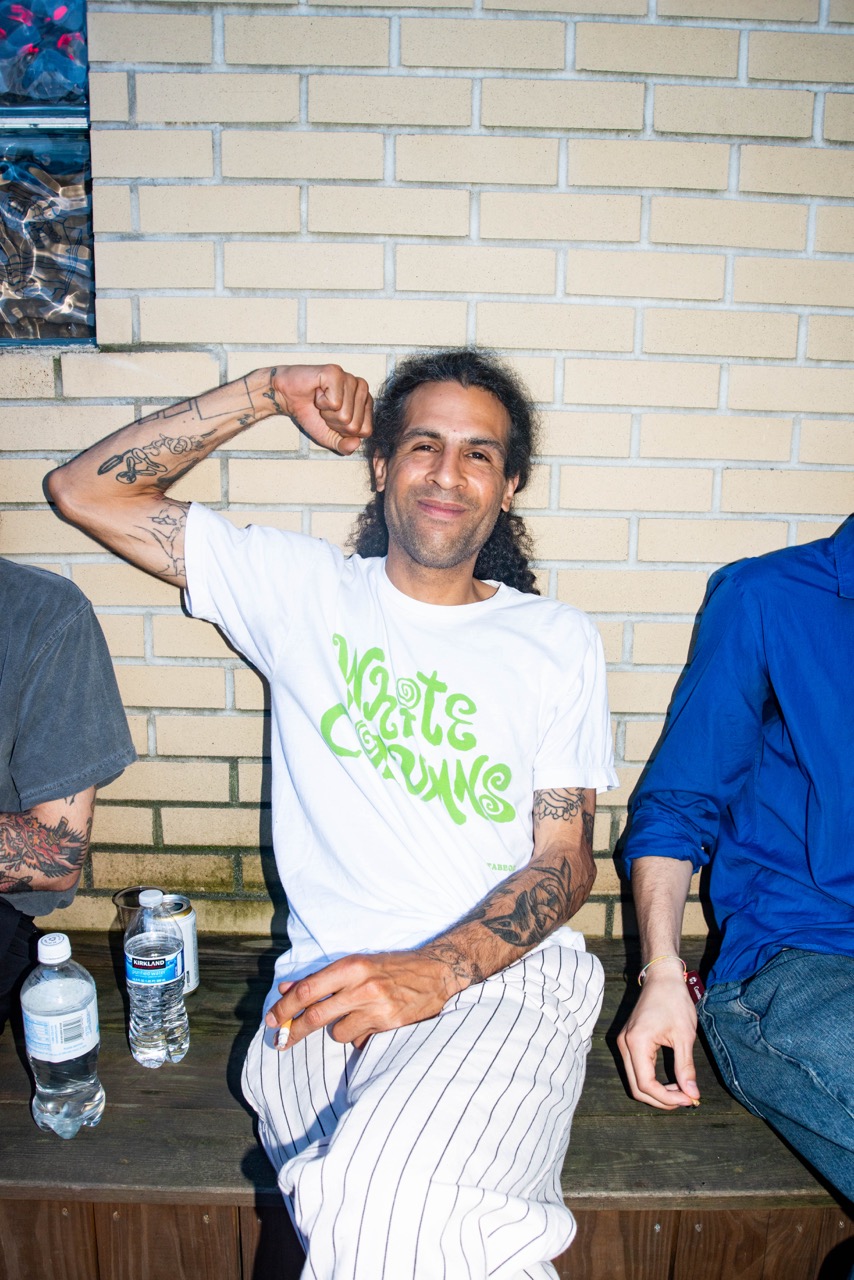

Check out photos from the opening night below and put your bids in here. The Artist and the Cigar Box online auction.

The Artist and the Cigar Box is on view online through June 30th.

Kobayashi Maru touches upon climate change, toxic grind culture, and mass media, all through Hascoët’s personal experience. The first chamber in the three-room show centers on his earliest influences: vats of Listerine, recognizable through their iconic shapes alone, alongside PS1 controllers and CK One, that ubiquitous, idealistic unisex scent. Lemons shout out Edouard Manet and echo tennis balls, a nod to Hascoët’s pup and Perrotin’s unofficial mascot, Simone. Three sharks prove that Hascoët, and society at large, have conquered the fears fostered by films like Jaws. Collective maturity has taught us that sharks are critical to earth’s ecosystem.

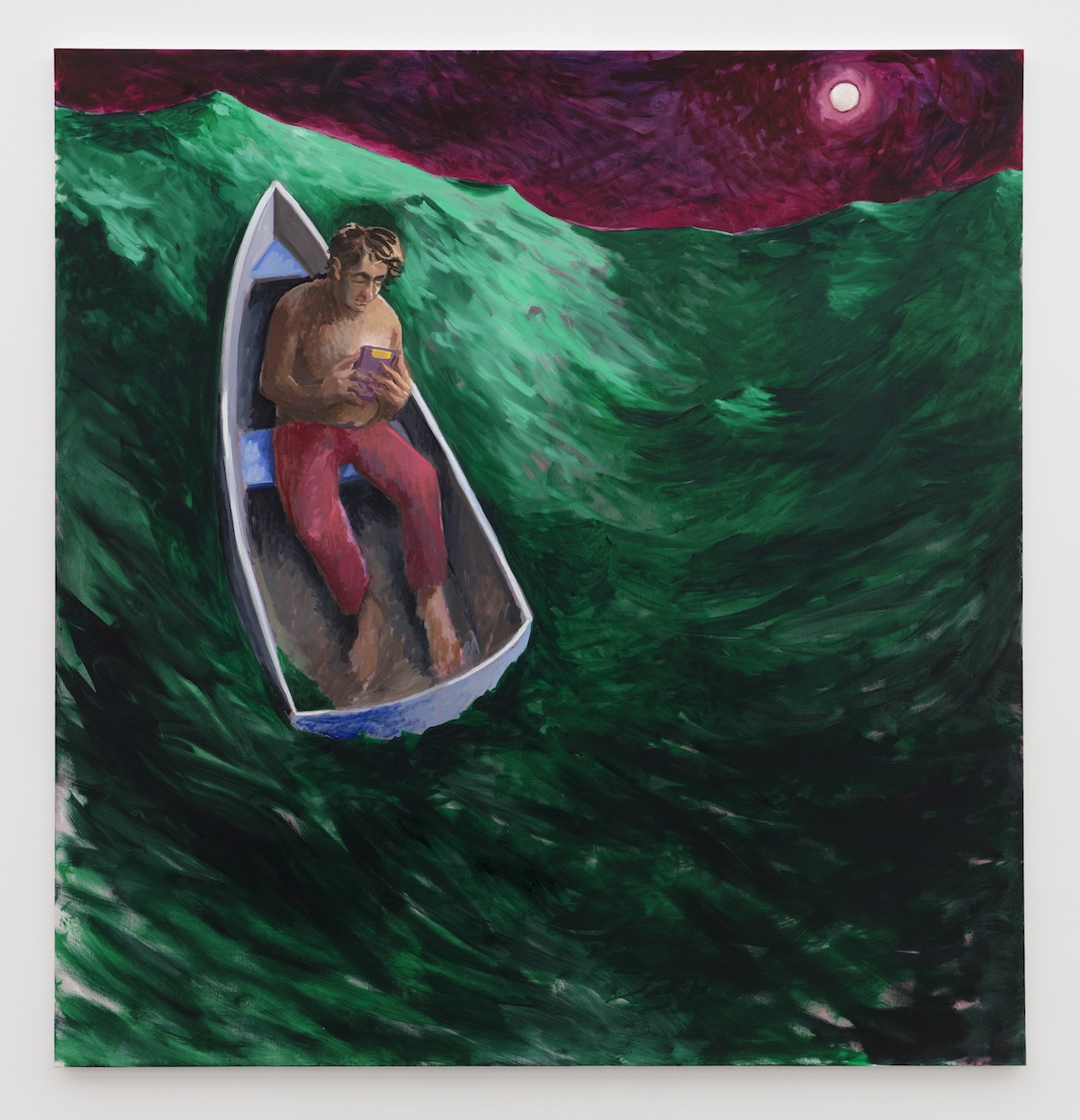

James T. Kirk, 2024

But Hascoët himself is the main character in the dream sequences that play out on larger canvases across the next two main rooms. In “The Waves,” Hascoët apathetically maneuvers raging seas in a dinghy, engrossed in his purple Gameboy. Those in the know will note he’s playing Pokemon, based on the yellow cartridge. Nearby, the show’s titular work depicts him sleepless, doom scrolling in a bed that straddles the tides and sands of a beach while a far off volcano erupts. The picture’s loose brushstrokes, underscored throughout by improbable pinks, contrast another self portrait across the way titled “Self Portrait with Brachiosaurus,” this time painted using a mirror rather than memory — with defined features and a rational color palette.

The real and imagined intertwine throughout. On walks to his studio, Hascoët discovered a store selling National Geographics for $1. Red pandas, dinosaurs, and polar bears have since entered his paintings, each bringing their own meaning. The advent of social media accounts attracting eyes with cute creatures has empowered red pandas to become the patron saint of a generation starved for joy. In “Red panda vortex,” this “kind of a new cat,” as Hascoët puts it, lounges in a magnolia tree inspired by springtime in Bushwick, on a branch jutting out over a water feature referencing Hiroshige. Elsewhere, Listerine makes one final appearance next to a red maple from his mother’s home, reimagined as a bonsai — or maybe it’s just a really big bottle of mouthwash. All depends on how you see it, much like the celestial bodies in “The Wave,” “Shiatsu,” and more resemble both the sun and moon. Hascoët’s not inclined to discern for you.

The Waves, 2024

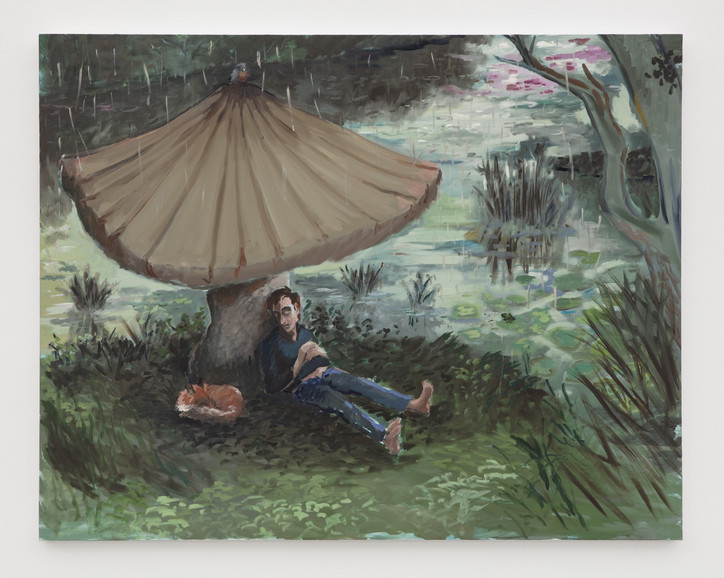

Shiatsu, 2024

Ambivalence and hauntology are the moment. As millennials have started entering their peak purchasing power and professional influence, 90s culture has proliferated contemporary art. It’s not a fad, but a mainstay — as emphasized by the art historical traditions Hascoët has translated such relics through, and rendered them alongside. He sympathizes with the desire for comfort in these uncertain times, but believes such motifs belie a deeper shift. “In the late 19th century, Nietzsche said ‘God is dead,’” the artist mused. “At the same time, Baudelaire came up with the idea that if God is dead, there is something to replace it. Why not poetry?”

Take it from both world wars — that didn’t work. “Then pop culture came along in the second part of the 20th century,” Hascoët said. “Poetry was quickly replaced.” Now, pop culture’s been used up. Rather than new stories, there’s a new Star Wars every six months. Kobayashi Maru doesn’t propose a solution, but honors Hascoët's diversions, like Polish-American techno DJ Bogdan Raczynski, who appears in a “Rave ‘Till You Cry” t-shirt. “I think it's a good way to implement poetry,” Hascoët remarked. “He would rip your mind open and then pour in some nice tunes.”

Cottage-core, 2024

Memes appear too. “Cottage-core” depicts Hascoët in his take on the “stop glamorizing the grind” meme. In the same room, Hascoët ponders his orb, right by another luminous scene based on the time Hascoët took Simone to a witch in Brittany to help her recover from getting spayed.

In fact, Hascoët’s grandmother was one of those witches, but when his father and uncle chose practical paths, the intergenerational chain shattered. Hascoët’s picked it back up again — and not without perfunctory tribulations. He failed at his first attempt to get into the École des Beaux-Arts, and heeded his father’s recommendation to try law school. Hascoët dropped out after two years, enraging his dad, then got into the École des Beaux-Arts courtesy of his renewed vigor for painting. Kobayashi Maru commemorates a decade since his graduation.

Hascoët believes the personal branding that characterizes Instagram and TikTok means the self will perhaps become society’s new god. His work has seized on that idea too, whether he wholly realizes it or not. While alchemizing disparate inputs like magazines, photos from friends, and his own observations, Hascoët only lets a painting leave his studio if he feels like it has soul. Interestingly, he says that without an element of self-portraiture that has nothing to do with the imagery itself, an artwork reads as vain. Even though he doesn’t appear in “Paleo-core,” the last work he made for this show, Hascoët sees himself in it. Whether he’s the T-Rex pissed off about the end of the world, the worried Brachiosaurus — or both — he still hasn’t decided. It’s up to you.