Miu Miu M/Marbles

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

Since her first presentation at The Kitchen in 1990 as part of the New Works, First Runs screening, Leeson has continually contributed to the institution’s programming, hosting TV Dinner No. 3 in 1999 — showcasing photographs from her Phantom Limb series and clips from her film Conceiving Ada starring Tilda Swinton — and participating in The Kitchen's 2019 Editions Portfolio. Desire Inc., currently on view in The Kitchen’s Video Viewing Room (and online through June 16, 2024), highlights four of Hershman Leeson’s groundbreaking works: Commercials for 'Forming a Sculpture Drama in Manhattan' (1974), A Commercial for Myself (1978), Test Patterns (1979), and Desire Inc. (1990).

Tonight, The Kitchen honors Hershman Leeson during its annual Spring Gala, recognizing her alongside visionary patrons Bernard I. Lumpkin and Carmine D. Boccuzzi, and the legendary composer Max Roach (1924-2007). Ahead of the Gala, Hershman Leeson joined The Kitchen’s Senior Curator Robyn Farrell to discuss television, the eclipsing rise of the internet, working across mediums, and finding resonance with an audience more attuned to the nature of her work.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, The Electronic Diaries, 1984–2019. C. Hotwire Production LLC.

Courtesy of Bridget Donahue Gallery, NYC and Altman Siegal Gallery, San Francisco.

Robyn Farrell — Lynn, I am thrilled to have the chance to speak with you, on the occasion of The Kitchen’s (TK) launch of your Video Viewing Room (VVR) program. We have had the distinct pleasure of collaborating with you on a number of occasions including the New Works, First Runs screenings in 1990, as the host of TV Dinner No. 3 in 1999, and as a contributor to the 2019 Editions Portfolio. We look forward to celebrating this history by honoring you at TK’s spring gala on May 22.

Your VVR program centers around four works (Commercials for Forming a Sculpture Drama in Manhattan, 1974, A Commercial for Myself, 1978, Test Patterns, 1979, and Desire Inc., 1988) that subvert the form and context of the TV commercial. You have described your TV commercial works as “electronic haiku.” Can you talk about what this means and what first attracted you to the medium of television as a means of creative production and reach?

Lynn Hershman Leeson — I believe every format of communication is a means of creative production, even if there is no history of it. At the time, television had the potential to reach far more viewers than an alternative space or museum. And television featured commercials, often ones that were extremely creative. But they are by definition succinct, and the messages need to be creatively reduced to the essence — hence "haiku". Commercials are always short and need their message to smack reality immediately. They are also delivered electronically (or were in those days, prior to digital haiku), so that's what the term came from.

RF — Will this be the first time your commercial works are shown online? Do you see this mode of broadcast (via the internet) as significantly different from their original circulation on public television?

LHL — I have shown my works before whenever I could, often online. The internet has a broader reach and relies less on the "framing of a program" but the consequences and context outline of what will be seen and who made it.

RF — The latest work included in TK’s VVR program is Desire Inc. made in 1990. By this point your work had already explored audience engagement and technological interface beyond the traditional viewing modes of television. Lorna, [earliest interactive LaserDisc, (1979-84)], for example, is the first thing that comes to mind, and how the physicality, tactility, and conceptual notion of “the remote” itself is central to your work.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Still from Desire Inc., 1990.

Courtesy and copyright by Hotwire Productions, LLC.

LHL — It kind of mirrors what you're watching, and I wanted to create a performance space that imitated the video space. Somebody engaging with the work had to simulate what was happening by using a remote rather than just turning the switch off.

RF — In your essay, “ART-IFICIAL SUB-VERSIONS, INTER-ACTION, AND THE NEW REALITY” (1993), you outline key technologies (telephone, automobile, television, and computer) that have disrupted linear structures of time and space. These watershed moments created models for “disengaged intimacy” as you call it, a term — in both concept and meaning — that serves as a mechanical prosthesis that extends human reach. Can you talk about how technology has informed your film and video work over time?

LHL — Wow, that is quite a question. I live in the bay area where a lot of this kind of technology was generated. It was important to me to use the technology of the time to talk about issues of the time. So whenever I learned of a new technology being released I designed a project that exploited it. There are a lot of works from commercials, to websites, to video and films, and each used whatever technologies were new or hadn't yet been used, whether it was 24k or virtual sets and everything in between.

RF — You engage the idea of mechanical prosthesis further in your Phantom Limbs series (1985-1987) which was included in the group of works you presented at The Kitchen's TV Dinner in February 1999 (The Kitchen’s TV Dinners ran from 1998–2004). The black and white collages merge female bodies with objects such as cameras, clocks, and televisions. As seen with your commercial broadcasts, this anthropomorphic series questions the seduction of media and surveillance systems that are embedded in our society. The anthropomorphic images presage contemporary notions of identity, vanity, and the female body, as filtered through ever evolving modes of technology. Can you share the impulse behind this series?

LHL — I integrated those ideas in the hope of making people aware how surveillance shifts not only how we see but what we see. Both are affected.

RF — You have said your early life experience with technology and the body informed your practice. Your Breathing Machines (1965-1967) being the earliest example both in your body of work, and one of the first sound sculptures in contemporary art. Can you speak more about the ways in which new technologies affected your work? How you pursued them throughout your career, and if there's a particular moment that stood out to you as a new mode of communication within your work.

LHL — I can't point to one specific one. Certainly Photoshop and PowerPoint, but really every new technology had things you could learn from and adapt work to. But I can't say that one in particular overshadowed the others.

RF — Photoshop in particular stands out to me, especially as it relates to the Phantom Limb series: You physically manipulated these works – cut and paste, right?

LHL — Yes.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Seduction (Phantom Limb) Series, 1988. Copyright of the artist,

courtesy of Bridget Donahue Gallery, NYC and Altman Siegal Gallery, San Francisco.

RF — This was second nature in the eighties but with the advent of Photoshop, it not only changed the duration by which one might work with a collaged image, but also shifted the engagement with material because you're no longer physically working with different types of paper, [one] was just working on a [computer] screen. I am curious, do you find ways to replace that tactile experience of hand to paper? Is working with paper and drawing still a part of your process despite the fact that it's become more technologically involved over the years?

LHL — Yeah, I do a lot of drawings and collages. So in that sense I still have the same experience, but for certain kinds of work, you can't do that or it's inappropriate to even think about doing that. So really it expands the possibilities of how one approaches work.

RF — I am similarly interested in the role of writing in your process. I first became aware of your criticism when I read Reflections on the Electric Mirror (1978). You've published numerous texts since the 1970s, how does writing factor into your visual work? Is it a parallel practice or interwoven within everything you do?

LHL — It's not parallel at all, but it is interwoven. The reason I started writing about my work was because nobody understood it, so I had to explain it. I had to do these little pamphlets to tell people why I did what I did because they didn't understand the technology of it. And if you want to make a film, you have to write scripts or have some other form to figure out what you're going to do. So the writing I think is a supplement to the other art projects, but it's essential to it. I rarely write just to write, although a book is going to be coming out soon that has a lot of my writing in it.

RF — TK’s TV Dinner series captured the ethos and values central to The Kitchen's mission. We are honored to collaborate with you again and bring that history back into light and celebrate it as part of our collective past in this present moment. When you hosted TV Dinner [No. 3], you shared slides and excerpts of your work, including Conceiving Ada (1997). Was that kind of program format unique to you at the time? Or just one example of a creative community gathering over food and cultural discussion.

LHL — I think people didn't know what they were doing, so they were looking for any kind of way to communicate and show work because there wasn't any fixed format.

RF — Your work now has incredible reach. What are your thoughts about your films now being available to stream on the Criterion Channel?

LHL — Well, I think it's great because all kinds of people can look at it, whether they know my work or not. It just makes access more available and expands the reach of people finding it.

RF — Yes, and I am glad you mentioned access because, to me, access brings everything back to these commercial works. I know that we touched on their dual function — both promoting and presenting — but they also had a didactic function as well. Access to a mass audience via broadcast is something that enticed many artists into experimenting with television as a site of production and distribution in the late 20th century. You’ve been a pioneer thinking about the ways in which your work can flow through the cultural landscape, whether through exhibitions in institutions or galleries, or online. You mentioned that your writing began as a mode of access to provide information about your work. So is it fair to say that access across forms of media and interpretation has been a driving consideration in your work?

LHL — Yeah, because people rarely recognized my work as art. In fact, the idea not art came I think in 1968 when I tried to show sound at the University Art Museum and they closed my show. So I have spent probably 50 years trying to get my work seen because work that I was doing that I felt was the most crucial and the most important and the most current people didn't want to show because nobody had done it before, so they didn't recognize it as art. So that's been a problem all these years.

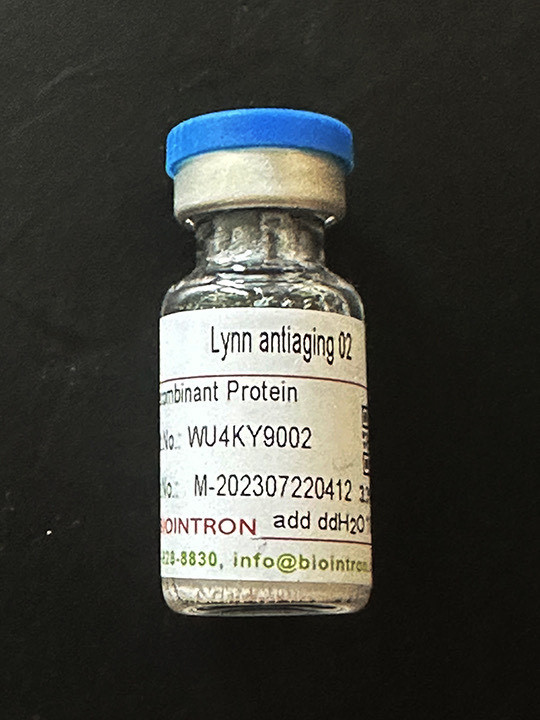

ANTI AGING VACCINE 2024, protein, animo acids plus related materials, 1" X 4" vial.

RF — Your recent exhibition at Bridget Donahue Gallery explores various meditations on the passage of time and the body, as chronicled through your work for the past five decades. The exhibition lays bare the prophetic lens of your practice that examines the influence of technology on human existence. Self-perception and self-reflection are long-running themes across your body of work. Has the idea of aging/anti-aging been an area of recent focus for you or something evolved over the course of your career?

LHL — I think it has always been part of what I think about because I was quite ill as a child and not expected to live past age 23. So I came to terms with death early, but aging itself and the process and effect of it creeped up on me, as it does everyone, and is a key part of not just contemporary thought but the products of our culture.

RF — For your new video Cyborgian Rhapsody: Immortality, 2023, you approached the script differently, by working with AI. Do you feel technology has evolved to a state where you have to adjust the way that you work when producing a film?

LHL — Because I said the premise was that the AI would write the script and I would've written a different script, and I think I would've written a better script, but I had to do it because that was what it was about. What would an AI have to say and what would their story be? A lot of people don't realize that I stayed out of the story making for that reason. That was part of the whole concept of why that video happened.

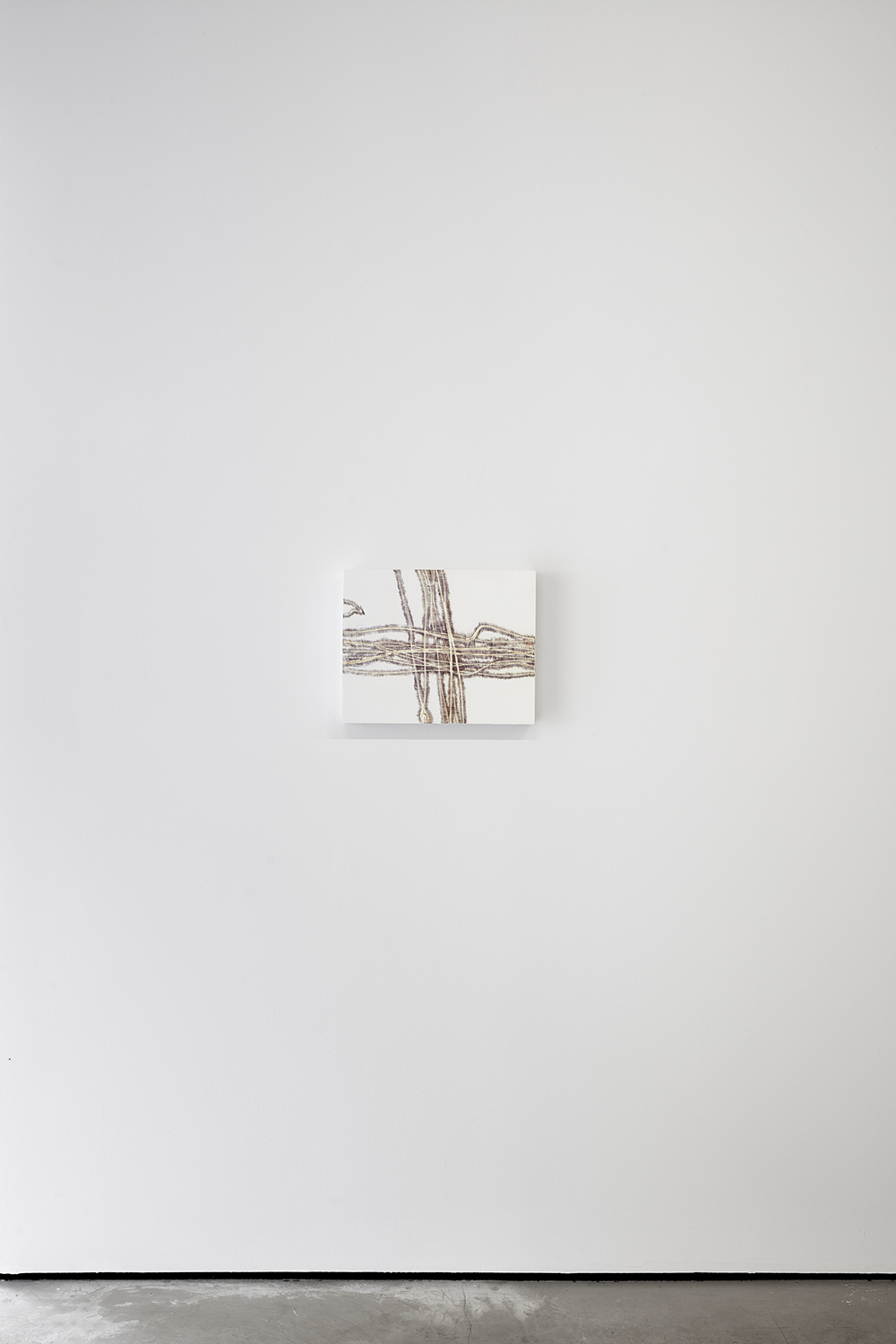

Her work, while somewhat abstract, is not true “abstraction” — the images Nguyen Quoc chooses to paint are what she calls “traces” — leftover, zoomed-in close-ups of photos she has taken. “Every day I see traces and images all around me, left by other people, by animals, by the passing and disintegration of time. My images and my gestures are common — basically I'm just a copyist, not a brilliant artist,” she says. “The better I choose my images, the better they will speak to viewers and (indirectly) put me in touch with others.”

The compositions are rooted in details, clues to where she has been and perhaps a map to where she is going. While their subject matter is indiscernible, they nevertheless “manage to relate to the viewer,” she says. “There is something common in them and in the way I reproduce them.” At first glance, it is unclear whether some of Nguyen Quoc’s works are printed images. Their flattish surfaces don't give much in the way of texture as paint often does. But upon closer inspection (which, Nguyen Quoc writes on Instagram, is recommended to view at “8 centimeters distance,”) alternate hypotheses on their constructions arise. Are they hand-drawn? The level of laborious precision is almost absurd.

Nguyen Quoc works mainly with humble materials — the show’s standout piece, also called Offering Body and Soul to A Radical Alterity, is a hand-drawn triptych made by using countless Bic ballpoint pens. To create the piece, Nguyen Quoc thrust herself onto the lifesize wood panel, surrendering herself to the work, and repeatedly drawing arcs that reflect the degree to which her arm was able to move back and forth. Imagining the petite, eloquent artist working herself both mentally and physically to her limits is truly awe-inspiring. As she speaks, a jumble of conceptual theory, anthropological terminology and scientific knowledge comes out in eloquent, well-phrased composition. Her paintings, similar to her way of speaking, dance between that exacting precision and free-flowing conception. Below, we caught up at her new show.

First off, can you tell me what grounds your practice? Is there a cohesive thematic element to your work?

Since the start of my practice, what has caught me and created a desire to inscribe something is what I call “leftovers.” That is to say, it made these traces that were not wanted, but in a clandestine way [are] a witness to the existence of life that were not represented. This remainder of something is not an object, nor a fragment, because we don't know what it is. It is something without body, which therefore has no iconographic language already inscribed.

Can you talk about the title of your show — Offering Body and Soul to A Radical Alterity? Were you influenced by Jean Baudrillard’s seminal text, “Radical Alterity”?

When I come face to face with a trace of an image that calls to me strongly enough to make me want to transcribe it, I will observe it and set up a whole protocol, like a ritual. I'll look for a gesture and techniques that will correspond to what I perceive. For me, the safest way to maintain a relationship with the world is not to interpret it, but to look at it factually and physically without ascribing particular meanings to things. In this position of copyist, I have to withdraw from myself to suppress my affect and fascination for the image. This is the only way that I can both understand the meaning of the image and also to encounter radical otherness — something that's absolutely not me. I think it is in this encounter with what's not us, that we can make the constitutive experience of humanity, that of coming up against plurality and differences without affixing our own desires to a thing.

What was your process for making the works for this show?

For this exhibition, I worked with the residues that my production and reproduction work had left around me. [For Drawing to Gathering Stars, these were], the patterns that emerge in the ink tubes of my empty ballpoint pens to the bottom of the ceramic cup in which I prepare my colors. It's the trace that I left when I produced other images. While making the color for that work, the pigment had left a thin film at the bottom of the cup, and I wanted to clean it by rubbing it lightly with a tissue. And when I lifted [it], this image appeared. I thought it looked like an image of a galaxy or an atom and its electrons. So we were going from the macro to the microscopic, and I had the feeling it was saying a lot about my work — at least the relationship we can have with it. I've been told that from far away it looked like a printed image. And once you get closer to the surface, it's like a whole world traced by mechanical hand. I think my work asks for this back and forth — moving away and then coming back to [it]. Because what we seem to see from far away is nothing.

Your process seems quite methodical and meticulous — there’s almost a scientific nature to it.

This is the most accurate way to translate the image without changing it. My images are sometimes outside the language of words. I'm often asked what they are. It's not that the question is not of interest, it's just that people see what they see. It's beyond my control. It solely depends on each person's lived experience. We can't necessarily put words on what we see. We can look at how it is done.

You clearly read and write a lot. How does language show up in your work?

There is a form of writing that is not made up of letters and words that can be read — humanity has always [done so]. We were reading the stars and coffee grounds and birds flying before language built and ordered the word. My work uses a more archaic language, the way we read the world around us, or the way we know that a river once flowed in what is now a dry riverbed. My gestures are mechanical, but a human action is never really mechanical. It's not just a matter of execution. Every technical action that I undertake is articulated by my sensation. The technical differences in my work are not stylistic effects, I simply have to adapt to the different iconography of my images.

Where would you say your influences come from artistically, or theoretically? Are there certain texts you refer back to?

Most of my influences are anthropological. My teacher, Dominique Figarella [at Beaux-Arts de Paris], is the one who told me, ‘you have to understand what techniques mean in your work.’ He advised me to read Marcel Mauss, who is the father of anthropology, and then I read Deleuze.

And how does that show up in your work?

The way in which [my works] are produced technically recalls ways of doing, psyches and lifestyle habits. [They] take on the human condition — the repetition and how we build our life and our psyches. They are not necessarily artistic gestures — they recall the gestures of an office worker or even a student at his desk copying something. Modernity pointed out that techniques participate in the experience of perception, and the question of language preexisted the distribution of signifiers.

What do you seek to get from your work? Or what is your relationship to it?

I wanted to understand the relationship with the viewer, because it's the only thing that puts me in relation with the world. I really wanted to be able to communicate and to understand why people are interested in my work.

In the press release for your show, it says that “if the thing seems to have potential for inscription, the potential to be a signal, then she works on it.” How do you know when there’s a “signal,” and the image you want to create?

I don't know, because my practice is not that domesticated. I think it's a good thing because I don't want to have to handle my work so tightly. I think this is why I draw things, because I try to understand the meaning of the image and why it was so strong to me. I had no choice but to make it. What I think will make me a good artist or not is to find the right images that will signal to people. Every trace can be a signal, because it is a trace of an activity. Homo sapiens evolved by reading the traces left in other spaces. We survived because we are able to read the traces in the world.

Your piece, Offering Body and Soul to A Radical Alterity is really incredible. It’s a giant triptych made from the humblest tool — a Bic ballpoint pen. Can you describe what your process for making it is like?

I trace [the lines] with many ballpoint pens. The size [of the strokes is] the size of the movement allowed by my arm. I discover my images only at the end. I put myself on it and I trace for hours. We can really know where my body was at the moment when I trace these.

What was the source material or image that it’s based on?

The image is a photo that I shot in school. It was a window ceiling covered in dust. Birds were falling on it, and their wings were scratching the dust. Light was coming through. This is an exact copy of the image. So this is not abstraction. It's a copy of what I saw — traces of birds who were falling because the window ceiling is not straight.

There's an element of masochism in the way you make art. You push yourself so far to create the image, it’s about seeing how far the work can go.

It's painful for sure. I'm getting a personal trainer who prevents injuries because I’m worried for my body. I work 12 to 15 hours a day. During my master’s degree, I came to the studio at 8 o’clock and I was leaving a bit before 9PM. So for that kind of work, I have kind of an urgency. I can't stop — I need to fulfill everything. The only thing that stopped me is my body. My work asks for time. If I want to produce a certain amount, I need to work a lot.

Offering Body and Soul to A Radical Alterity is on view at Gratin gallery until June 7 2024.