Miu Miu M/Marbles

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

On our call, they’re immediately lighthearted and candid, and it’s easy to feel how close and effortless their dynamic is. Right before we spoke, they signed the lease for their newly shared studio space, and have been inseperable lately, playfully dubbing each other “the best boyfriend they never had."

The pair spoke to office about being each other's soulmates, their separate practices, and the art world.

Okay, first, I want to hear about how you met!

Ariane Herloise Hughes一 It's a bit of an origin story. We were sort of Instagram admirers of one another through lockdown because openings weren't happening and people were working from home. Our careers parallel one another in that sense because neither of us had the time or the space to just focus on painting until lockdown happened. So, we were making work, we were talking through Instagram, and then the world opened back up again. Vilte thinks we met organically, but I had just been sort of stalking her on Instagram, trying to figure out when she was going to have her next opening, and just sort of inserted myself and tried to play it off super cool. I approached her and complimented her outfit and her work.

Did it work?

Vilte Fuller— Yeah, it worked ‘cause I thought it was an organic meeting ‘cause I was like, She's way too cool to want to speak to me. And she's just being polite. My trousers are really not very cool. And she said, Your trousers are so cool.

AHH一 We hung out loosely since then — but we had lives, we both had boyfriends — and then it was only the end of last year that…

VF一 We've talked everyday 24/7 since September 1st.

AHH一 Vilte’s the only person I trust to give me advice on my work.

What do you think makes you such close friends?

AHH— Our work is quite different, and we have had quite different upbringings, but we have met various milestones at similar times, and in our own various ways had parallel existences.

VF— This doesn't usually happen with people our age — and particularly with painting. We are having incredibly parallel situations where we can speak to each other in a way where there's never any jealousy, or any like, I can't believe you got this and I didn't get this. Everything is different enough. But then we're also on such similar levels.

AHH一 That's how I know that you’re the love of my life and my best friend in the whole wide world because I'm never jealous of you. When you tell me something, I'm actually genuinely so happy. But I also guess it's kind of out of a needs-must situation because the way the art world operates is it's not transparent at all.

VF一 There are great people and galleries, but it's not everywhere. It kind of feels like people are maybe doing certain things because they wanna get something out of it rather than like a genuine human experience.

AHH一 Yeah, and it's difficult to know who to trust and what advice to take. And especially through art school — I feel like that's where you're really let down. There's no education surrounding how to operate as a small business, or how to get into shows, or what to do. And you just have to pick this up along the way through trial and error. Trust me, we've both had our fair shares of absolutely horrendous business decisions.

VF一 That part of it I still struggle with. We're getting better honestly. I think because we've gone through the kind of cliches of everything they say don't get into, we've gotten into. I've managed to come out the other end of it. It's fine.

What advice do you have that you've taken away from what you’ve gone through in that sense?

AHH— Well, the first show that I ever had, it was during lockdown and I saw an open call, which I applied for and I got, and it was in Japan. A very small gallery no one had ever heard of. I had to pay for my own work to get shipped there, and then the gallery very quickly went bankrupt, and those paintings are nowhere to be found. I think the Japanese government at some point got in touch with me, but I feel like that was also a scam — I don't know.

VF一 All the commissions with galleries most of the time are 50/50, so understand what is your 50% and what is theirs. You pay for your studio; you pay for materials; you make the work. You shouldn't be paying for your own transportation; you shouldn't be paying for photography. Have a payment contract. Nothing operates with anything really written down apart from WhatsApp messages and emails. And you don't see money for six months. The gallery has that money, and they're keeping their money 'cause they need to deal with their own stuff, And then you’re always at the bottom end of the barrel, even though it's your work that’s being showcased. The show is supposed to be about you, and you're the last person to see those funds. So many artists never get the money that they’re owed because people go under, and all of a sudden it doesn't exist, and it's literal theft.

AHH— Contracts are really important. When I have time — and I'm hoping to make it a yearly thing — I've also been curating shows. The first show that I curated a few years ago, I had no contract with them. Nothing about payment was in writing. It was always a phone call.

VF一 Get everything in writing.

AHH一 I took a phone call, and the gallerist of this space that I used to curate the show talked me into selling a piece of mine that wasn't in the show, that a collector wanted. I didn't want to sell it in the first place, and didn't need to sell at the time. I was holding onto it for nostalgic reasons. He guilt tripped me with his own financial issues, so I agreed to it over the phone. He sold the work, and I still haven't been paid for it. That was years ago now, and it was a decent amount of money as well. This guy is still out there doing this.

VF一 I think artists are really scared to talk about money 'cause it's seen as just being ungrateful for the opportunity. But opportunity doesn't pay your bills; it doesn't pay your rent. We need to be collectively transparent about money and discuss when things are not going right 'cause so many people are getting away with so much because nobody's talking about it.

AHH一 It's essentially money laundering.

How would you describe each other's paintings?

AHH一 My USP (unique selling point) is “creepy, sad, sexy” paintings.

VF一 You prime five layers, and sand things, and are almost so physically violent with the surfaces to make them as smooth and as perfect as possible. The process is so laborious and work intensive, but making it look effortless. It’s like that saying, “there's no beauty without pain,” that's what your work feels like.

Does that feel intentional? Did you make the choice to focus on this part of yourself that you consider “difficult”?

AHH一 It's definitely personality driven. I grew up Catholic — masochism sort of comes with the territory. I paint an oil — again, a masochistic process. I hold very high standards for myself and for the people that I let into my close circle, which is why my close circle basically consists of Vilte and my mom. It lends itself to my creative work ethic, and the fact that I think I make work that separates itself from the more fast-paced approach that the contemporary and emerging arts scene takes.

VF一 There have been many cases where people have suggested for her to take shortcuts to what they think would be the same image, but it wouldn't be. A lot of people assume if Arianne started using airbrush and acrylic paint that dries really quickly, she could do this 10 times faster, but it would not look like her work without her technique.

AHH一 The whole point of my practice is the process and the fact that it takes time and the way I source my imagery, the way I put together a composition, and then the way it takes weeks to execute. I'm commenting on this fast-paced digital age and the age of narcissism and the spectacle and the way we view things through online spaces in a traditional medium to poke fun at and critique it. What I would say about Vilte’s work is… Vilte is going through a bit of a rebrand. A “cultural reset.”

VF一 It's basically very reduced form. I'm doing less figuration. The colors are more muted. I'm trying to make it slightly less garish and maybe a bit more classy. It still has elements of sci-fi and all that stuff.

What made you decide to make that shift?

VF一 My work has always been slightly dark, creepy things with humorous elements. That was great at the time for my interests, but when I was looking at other works by other artists that I like, or just narratives that I'm interested in, my preferred tastes are a lot more muted and more abstract. It's not like the work is now serious, but before everything was very facetious and in joke. It got to a point where it felt like I was just recycling the same stuff. I started to really focus on asking myself what my actual personal tastes are and what I like.

AHH一 What I love most about Vilte’s work is her process and how she actually apply paints and creates the surface — how playful she is with how she puts together her surfaces. We're polar opposites. During lockdown, she was sewing bits of canvas together when things were closed. Now she’s carried that through, and I love seeing that in her work still. There is a DIY element, which I generally hate in artwork, but she has such a good eye for it, and understands the history behind it. It's not just messiness for messiness sake. The work now is not as in your face and figurative, but it's not serious or boring. It's still her, and there's still the element of play and the element of critique, which I think is so important to her practice.

What are some of your current references?

VF一 It's like Succession meets David Cronenberg. Being around London, there are a lot of metal buildings. I have this obsession with work in general. For the past year and a half, just fully sustaining myself from painting and kind of getting everything I would've ever wanted as a child to be like, Wow, I can sustain myself purely from painting. There's been elements where I really miss normal work and I miss routine and I miss being a part of a community where you go in and you see these people all the time. I got obsessed with the idea of work culture through spending a year and a half purely painting since it's so lonely. You have to be so determined and self-motivated and have so much belief in yourself that I do think you have to be a certain level of a narcissist. And I always thought that I was narcissistic enough, but I don't think I am. My new body of work has been very much based on the idea of work and then me being me. I love a little sci-fi horror narrative going into it. I’ve been looking at the popularity of financial and political dramas in film and television. Similarly to my other previous work, I reference movie tropes. The new work is very gray, very corporate — slightly fleshy and slimy — a little bit gross, but not too gross.

AHH一 The way my practice operates is I turned a bad habit of mine — which is incessantly scrolling through Instagram, consuming unnecessary visual media, and death scrolling on any and all social media platforms all the time — into a creative outlet. I end up in these weird rabbit holes on someone's profile; I don't know who they are, I don’t know where they came from. Generally, these people will only have a few hundred followers and I'm still creeping on their stuff — taking screenshots. On my notes app, I write down thoughts that I have; titles; things that have been happening or have happened to me. It’s this combination of narratives that are personal to me, and then these images that I found, but don’t relate to me. Mixing very mundane shots, which are completely distant for me, with these very personal memories of mine, and merging them together into these compositions that make sense, but don't make sense — that are familiar, yet out of reach. There’s sort of a Lychian, uneasy feeling to them.

Lately, I’ve been looking at dog mouths. I’m really interested in dog teeth and fleshy gums. I think the juxtaposition of the soft fleshiness with the hard teeth is really interesting. And obviously all the sort of symbolism around teeth and your teeth falling out in your dreams. Something that's always on my mind is traditional religious iconography and religious themes, and merging them with more modern ideologies and images.

I wanted to ask you about the swan motif in your paintings too because I love swans.

AHH一 I am obsessed with swans. In Australia, they have the black swan. You don't see them so much in London, but we have the white swan, which is the queen's bird. When I'm feeling sad, but still able to leave my bed, I'll go and watch the swans. I literally have a folder on my phone of over 5,000 images and videos of swans from Hyde Park. So, I always have these references that I can return to whenever I need a swan reference. Symbolically, what I love about swans is obviously they're the picturesque symbol of love. You see them on postcards; they mate for life; all that sort of imagery, but then compared to the fact that they're quite a violent bird. I like this juxtaposition of eternal and forever, but also aggressive. In terms of the shape, they're quite phallic looking, so it's this idea of something so hard against something so eternal yet ephemeral. That's why I love a swan. Also, if you really watch a swan, they are magnificent creatures. You can't buy the white swans, but you can buy the black swans, and a pair is around £600, which is totally affordable, but obviously in order to properly house them, you need to have an estate with swamp. If I ever make it big time, I’m going to have an estate somewhere out in the country and breed black swans — that's my plan.

[Originally published in office magazine Issue 20, Fall-Winter 2023. Order your copy here.]

What is your ideal office?

An open space, comfortable. I relate more to the idea of a studio than an office; natural light, spacious, lots of books, a living room to digest thoughts and consult, and a kitchen where I can make chocolate.

How often do you sit in silence?

Often, at different times, I’ve learned to be flexible with myself, identify how I feel and act on it. In the mornings I can meditate or read, other times I just need to hit the streets for a walk and those moments of introspection happen as well when I am in movement. Other times after lunch I do a protocol called NSDR for 11 mins, giving me a good mental break.

What is your relationship with texture?

It’s somewhat intense, I am all about it; paper, chocolate, people's skin, fabric, wood, bread …

If you were an ingredient what would you be?

I would be black garlic, sweet and flavorful.

What's the most memorable piece of advice you've ever received from a stranger?

Smile.

What would you do if you lost the use of your hands?

Jesus, just the thought of it …

How is the internet a part of your design vocabulary?

The internet is a medium to me, a source to find, a source to get lost, a source to communicate.

What is the most interesting thing in your trash can?

Buckwheat sourdough from last week. Unfortunately, we didn’t eat it before it got hard.

What is the last thing that made you cry?

A documentary – Apolonia, Apolonia by Lea Glob.

What makes your heart beat fast?

When I get a text message saying, “We need to talk.”

What’s the last item you lost?

My AirPods.

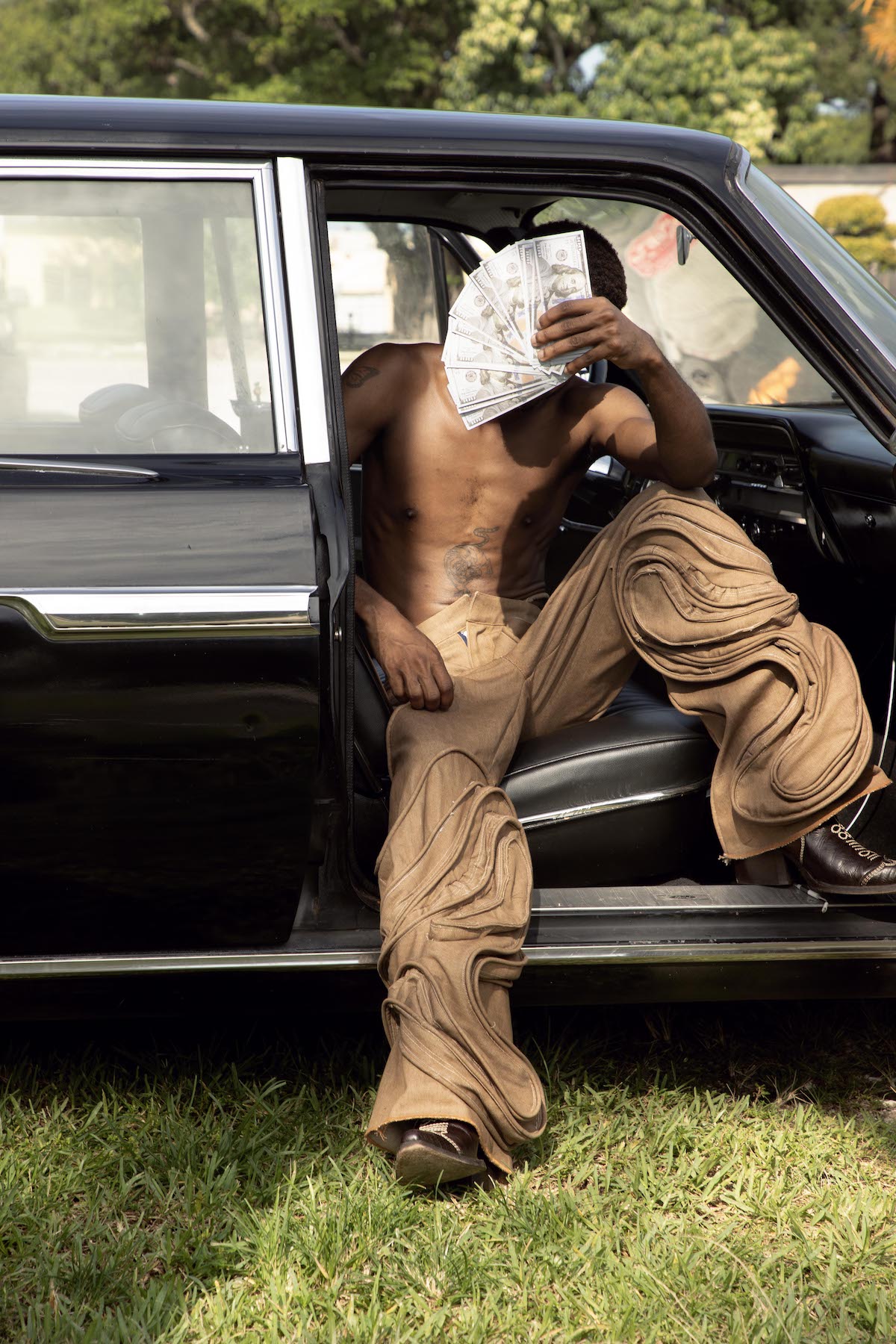

The designs themselves reimagine the potential of denim as a leading material; transforming the textile both physically and symbolically through bleaching, Baptiste simultaneously examines the storied role of denim in American identity and uses it as a site for cultural dialogue. An accompanying film created in collaboration with Jordan Blake and the Black queer collective MASISI documents the rich and vibrant beauty of Little Haiti's ceremonious spaces, alongside a series of photographs of the collection shot by Baptiste. Approaching the closing week of the exhibition at MoCADA in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, office sat down with Baptiste to discuss his creative journey and the inspirations behind Ti Maché.

Samuel Getachew— Hi Daveed!

Daveed Baptiste— Hi! How are you?

SG— I’m great, congrats on the show!

DB— Thank you, thank you!

SG— You combine fashion and photo in the exhibit in really interesting ways. Where did your creative journey start for you? Which medium came first?

DB— My first medium was definitely photography. I started shooting in middle school, I want to say like seventh or sixth grade. At the time, I was living in Miami, Florida, not Miami specifically, that's that's like, you know, my first home. And we were at this after school program at MoCA [Museum of Contemporary Art], and they had a teen program, similar to how the Brooklyn Museum has their teen program.They had different classes every single day, and I really came into myself in those classes.You know, you're young, you're discovering yourself through a creative medium. And for me, that was definitely photography.

At the time, I feel like images weren't as accessible as they are now — we had smartphones, but the quality of the iPhones weren't that great. So it was really about the point and shoe that your grandparents might still own. And if you had a DSLR camera, I mean, that meant you really had money to spend on a camera. So I discovered images that way. And I would say fashion kind of came afterwards.

I felt like photography was more natural for me, it kind of felt very spiritual. Not in the moment, but now that I have the language for it. And then design was this learned thing, that I'm very passionate about and I love, but I just have a different relationship to it than I do with photography. And people often like to ask, “if you had to choose one,” and I'm like, I’m not choosing.

SG— I love that! Was there a moment for you with photography where it went from this cool thing that you're getting to do in this program to something that you saw yourself taking seriously? When did you start considering yourself a photographer?

DB— I think when I moved to New York. When I was like 15, 16, I was going to house parties in Miami – I loved taking my camera to the house parties, and photographing people. I loved watching people's reactions to seeing an image of themselves at an event or at their best moment, whether that's like their wedding day or baby shower. But when I moved to New York, I started seeing really young people, like kids who are 19, 21, 23, shooting campaigns, shooting things for huge brands, shooting for big magazines and editorials. That’s when I realized, this is a real thing.

SG— Yeah, totally. I definitely know that feeling, like you see it, and then it kind of lights a fire under you. How did you start working with fashion and textiles? Did that begin when you started going to Parsons?

DB— When I was in Miami, I went to a school called Design and Architecture Senior High School, or DASH. It’s a very special school, a lot of amazing people have come out from that school who are now practicing creatives, in all different fields. They had a fashion design program.

It's a magnet school, which is technically like a public school, but you had to audition to get in. Most kids got in their freshman year, but they rejected me three times. I had like, really bad grades. I knew I was just as good as all those kids in the school, if not better, but I wasn't the full package. I was a kid from the hood, who just was not very well behaved with shitty grades.

We had a teacher named Rosemary Pringle, and I learned how to sew in her class as a junior. At the time I didn't really feel like I belonged in fashion. And I remember, this was around the peak of Hood By Air, so I think kids my age across America, and across the world, were watching New York culture, watching Shayne [Oliver], and that that was special. It was the first time I had seen someone Black in fashion like that.

SG— With this show, were you thinking about the garments first, or the images first? Or did they both come to you at the same time?

DB— I was thinking about both simultaneously. When I create garments and pieces, I'm also imagining the world that it lives in, visually and culturally, its presence in a space. When I was creating the collection, it was material first. It's an eight look collection, and most of the pieces are in denim.

Denim really speaks to so many things — culturally, I think spiritually, for a lot of people. I feel like it's the people's fabric. It's the people's material. There are so many young folks who start designing, and denim is their first choice. It's one of the few textiles that can transform so many different times: it could be etched, it could be printed on top of, you can put a puff print on there, it could be laser cut, there’s all the different washes that exist, all the treatments, it ages over time.

Before I actually started doing photography, I was drawing with my brother. Now it feels like I've been drawing with denim – the actual material, it feels like you're painting with it, like you're drawing with it. I love the way it wears. I love the different faces that it has over time, and how you can control them depending on what you do at the factory.

I'm a designer who approaches materials first, and I let the materials lead the rest of the design, lead what the silhouette’s going to be. I really wanted to push what denim could look like, what new washes we could invent. I feel like every decade and every generation does their thing with denim, and we keep reinventing and reimagining it, so this was me trying to scratch the surface of what this world would look like for me.

SG— Totally, it’s interesting to see how over time, when fashion trends cycle through, it's not that denim cycles in or out, but the cut of the denim changes, or the wash of the denim changes. But it's still always there.

Typically the way that people view a designer's work is through a fashion show – so you're seeing the garment in passing, in one quick moment on a model, and it's this very ephemeral thing. What do you think the effect is of having the garments in the show, static, alongside their own images, as opposed to just having people view just the images alone or just the garments alone in a passing moment?

DB— I wanted to give people an immersive experience that they kind of had control of, in the sense that you can decide when you come into the space – versus on a runway, the moment is fleeting. I think an exhibition is so much more liberating.

Fashion has always been exclusive in so many ways. By presenting the garments and the exhibition for two months now, I was able to reach so many people: from folks who are in highbrow culture, to folks who are in Fort Greene walking down the block, from people who saw on Instagram, they all really got to go and experience the work. I wanted that freedom and liberty for the work in itself, for it to be able to truly breathe. I grew up in the art space, in museums and galleries. As much as the fashion community is my people, my village is the art kids. So I wanted to bring a fashion energy, but into an art setting. I got to tell the story of Haiti and the Caribbean, I got to tell a story about migration, I got to have very specific details in that exhibition that you wouldn’t be able to get through a runway show, or the way that other institutions have done retrospectives or fashion exhibits. And I want to shout-out Amy Andrieux, the curator at MoCADA. She worked day and night with the museum and with me to elevate it to the highest level possible.

I really, really love working in that museum space and I want to continue to. I’m also seeing my contemporaries and some of my peers enter that space. Taofeek [Abijako] from Head of State had an installation at Strada Gallery last fashion week. People are slowly entering that space. It's very exciting. It's more cost efficient. It's more democratic. It can access more people.

SG— You went back to Miami to shoot the collection, which I loved. Could you tell me about that decision, and the role that the city played in influencing the collection?

DB— I came from Haiti at six and moved to Miami with my family, where I grew up. That’s home. I wasn't even doing it, like, in a “I'm here to honor my community” type of way. I just really fucking love Miami, and I love what the young folks are doing, and I love the neighborhood I come from. I come from Little Haiti, and North Miami. I love the rich Caribbean culture that's there, specifically the Haitian community.

I knew I wanted to work with MASISI collective. In New York, we have so many Black queer and trans collectives – as much as we're still the minority here, the city has an influx of really awesome spaces that are being built for our community. But Miami has so few, specifically for Black queer and trans folks, and MASISI is so special.

Akia, the founder of MASISI and also another fellow Haitian, produced the shoot and they casted models for it. So they were pulling from their collective, or pulling from their network of creatives that are cultivating culture in the 305. They were also scouting the locations. And a lot of those places that we were shooting at are places or environments that are pivotal to Little Haiti – spaces that may not exist in 10 years, five years, maybe even one year. Little Haiti is one of the most rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods, in Florida and in the country. The land that Little Haiti sits on is super high up above sea level, and Miami is drowning, so there's been a huge push to purchase the real estate there and push people out of the neighborhood.

Like I said, when I'm making these decisions, I'm not doing it for all of these reasons, I'm not a hero in that way – I'm doing it because I really fuck with my neighborhood. But here's the context of what's happening. For me, it was really about bringing Black Miami culture to a broader audience. When it comes to the music scene, we have cool people that came out of the 305 who get a global audience – you know, we love the City Girls, we love Trina. But then, when it comes to fashion, like designers and painters and photographers and film and actual images from North Miami, that doesn't make its way into the mainstream.

SG— I love that. Could you tell me about the film you made with MASISI? And what role film has in your practice, as a new medium for you?

DB— Film is very, very new for me, like yesterday new. We shot with freaking legendary, amazing director, filmmaker and photographer Jordan Blake. They're like a triple threat, which I love.

We met in New York, we’re friends and he knew about the project. So many friends knew about what I was doing and saw the work progress over the years. And I was like, “Yo, can you please film this,” and Jordan was down from day one. There was something really special about this person I had only met a year ago, trusting in my vision and loving what I do. And also our aesthetics are very different, but similar in the sense that we want to portray Black people in the most beautiful way through our own aesthetic decisions.

He didn't ask questions. We had like literally one meeting. And he stayed with me in Miami for a whole week and we filmed. We have all of the visuals that I shot, but then Jordan brought an extra layer of storytelling with the filmmaking with these beautiful cinematic images and stills. When I saw the film, I was like, Holy shit, I can't believe you just shot Little Haiti with this sexy ass camera. Cutting and editing was a collaborative process with Jordan, myself and my family. My little sister just moved from Haiti a year ago. She's 21, and I love her perspective. Having her help me with sound design, that was really sweet.

Ti Maché is on view at MoCADA Culture Lab at 80 Hanson Place, Brooklyn NY until December 30, 2023.