Miu Miu M/Marbles

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

For her solo exhibition Open Arms at Anat Ebgi Gallery, which opened on Friday September 6, Dicke debuted a new body of works that continues her exploration of the signs and symbols shaping how we view the female form. In Open Arms, she expands her focus to include men’s fashion ads, art catalogs, and art history books. What connects these different interventions into modern masterpieces and male model photoshoots is a defiance of the convention that reduces women to passive objects of desire within images. At the same time, Dicke embraces the human tendency to project desires onto these images, making her revisions both sensual and fluid. Open Arms can be seen as a love letter to the art of self-representation, while critically examining what it means to engage with these representations.

Hi Amie. I’m really excited for your show at Anat Ebgi Gallery. I want to start by asking about how you first came into the art world. You were a model in New York in the early 2000s, right?

This story has become a thing of its own. I did live in New York for a year and a half as a starting artist to follow my then fresh love, but I did not model. I only worked as a teen model in Rotterdam. I was too shy to be a good model. The camera made me feel very vulnerable. I love fashion. Still, I prefer to stay on the other side of the camera. In Rotterdam, I also made sculptures and got some attention fresh out of art school. Somehow, making sculptures did not feel viable because of how masculinist it is in Europe. Instead, in New York, I found myself through all the imagery I saw on the street advertisements and magazines. Everything felt insanely new for me. I even learned how to navigate the subway because of these huge Calvin Klein posters. So, I started drawing on them and cutting them away.

What made you particularly attracted to images of young women found in fashion advertisements and magazines?

I am fascinated by how images of thin, young women are constantly pushed onto us. They often link back to archetypes like the muse or the Holy Virgin. I was studying old portraits of Mary and realized how her posture or gaze can reveal esoteric meanings. The same thing can be said about the innocent young girls I see in fashion imagery.

And you mostly construct images of faceless women in elaborated contexts, be it clothing or setting, which can be quite telling. I am curious as to why you are not fully denying our access to these women’s psychology.

My working process is full of discoveries. I rip pages out of magazines or art books, scan them and blow them up, and reproduce them on archival paper. Throughout the process, the images speak back to me, hinting at what to leave untouched and what to scrape away. In all cases, the images end up having this dualistic quality, somewhere between absence and presence. The women in my works reject the viewer's desire to identify with them but at the same time demands more attention. I find this doubling gesture very alluring, as if they took on the eternal quality of historical portrait painting.

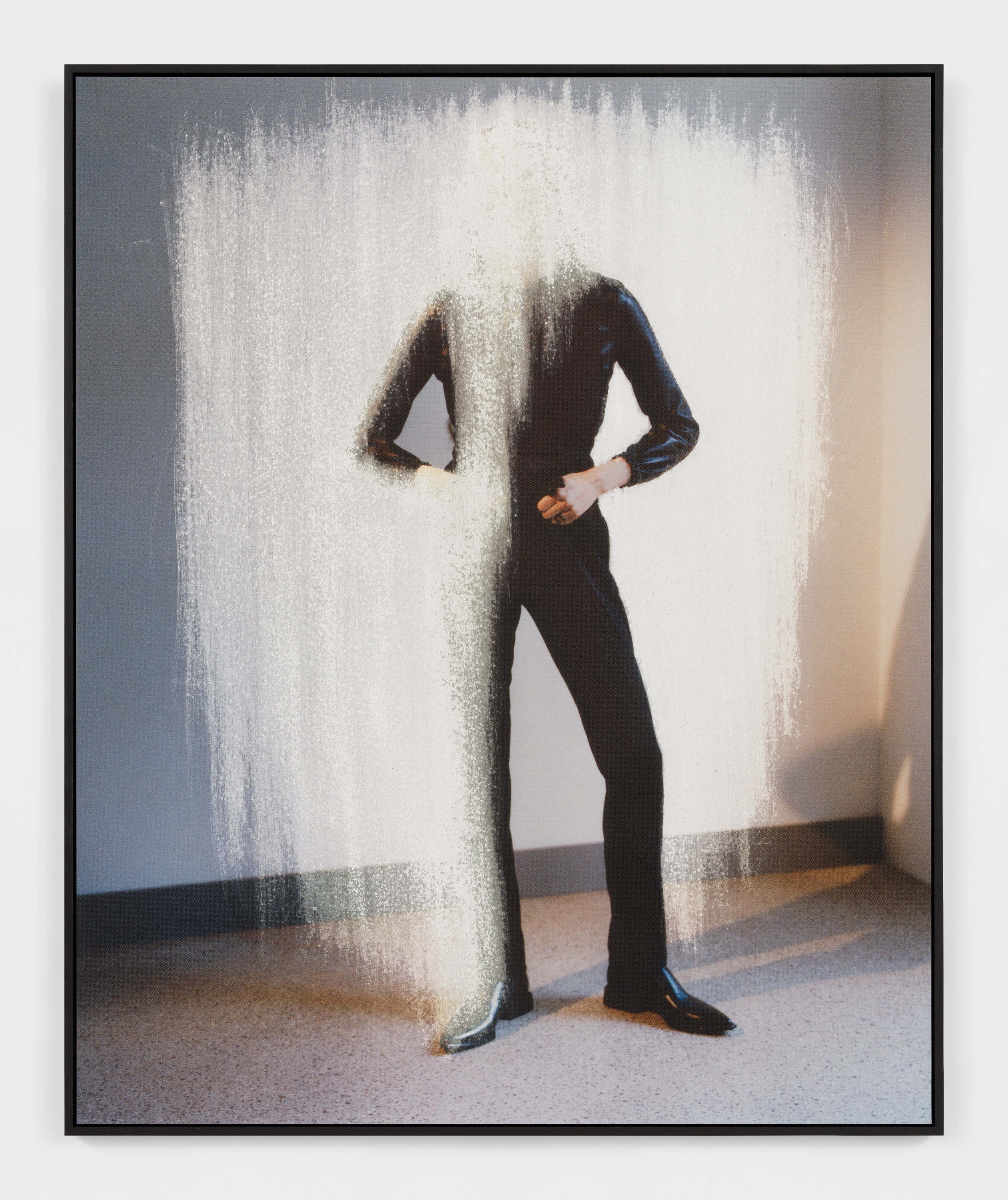

Amie Dicke, Zeitgeist, 2024. Courtesy of Anat Ebgi Gallery.

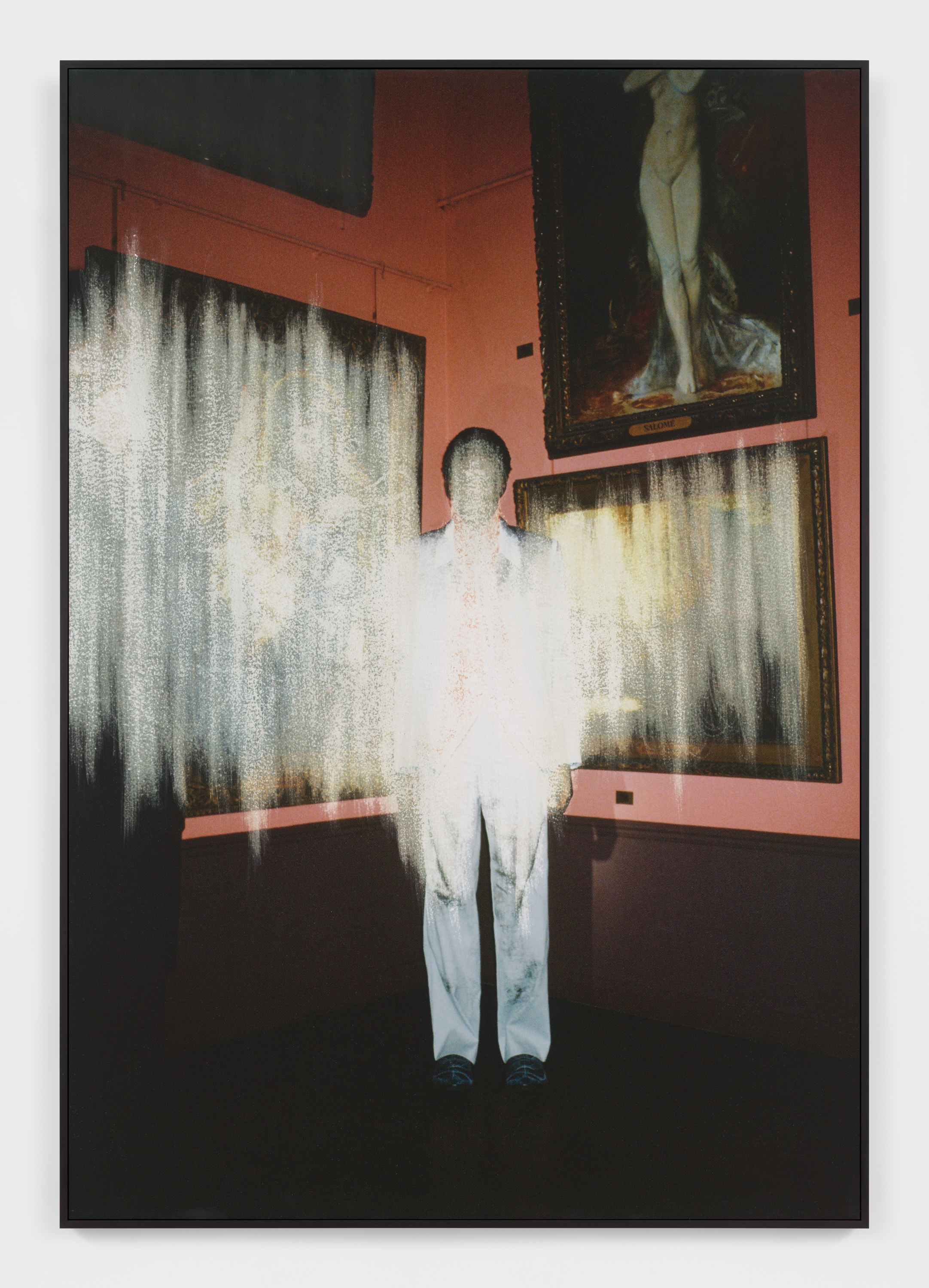

Amie Dicke, Salomé, 2024. Courtesy of Anat Ebgi Gallery.

I also noticed that in this new body of work you have started to work with images of male models. The figures in Zeitgeist (2024) and Salomé (2024) have a more masculine build.

I realized there is something about masculine features, either square face shapes or bigger shoulders, that lend well to my abrasion. The Salomé piece is close to my heart. It was originally a magazine shoot of a male model standing in a museum, with several paintings behind him. I have always been interested in looking at the photographic reproduction of paintings, thinking about how they come to us and what we learn from them. While looking at the image, I saw a nude painting in the top right corner, with her face perfectly cut off from the frame. However, I can still identify her as Salomé by the antique placard placed on the painting’s frame. I was thinking about censoring the title but soon realized how perfect it is in relation to the faceless male model in the front. Salomé famously requested the beheading of John the Baptist.

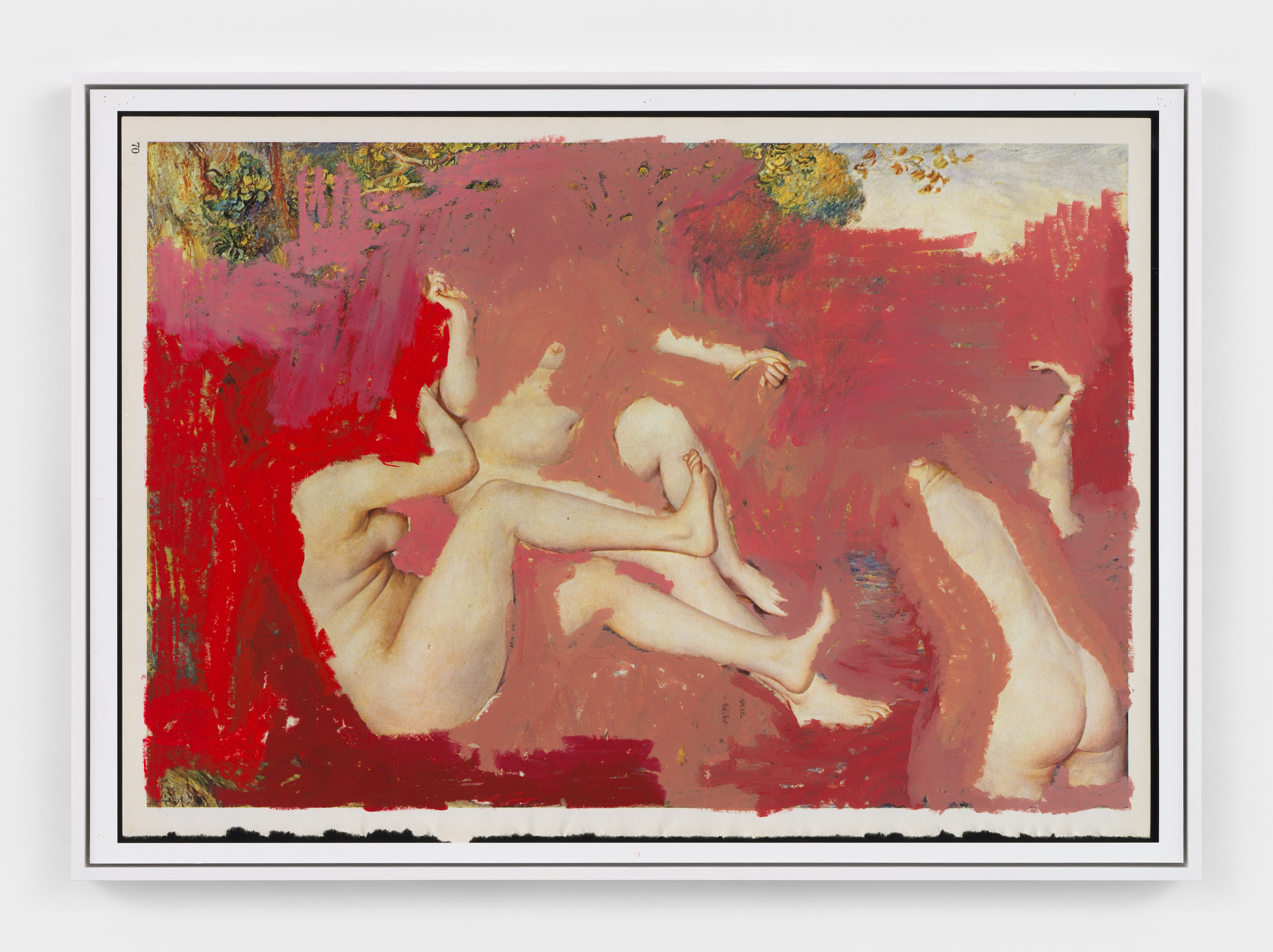

Amie Dicke, The Bathers, 2024. Courtesy of Anat Ebgi Gallery.

Amie Dicke, Nude, 2024. Courtesy of Anat Ebgi Gallery.

You’ve also started working with the history of Western art itself. The Bathers (2024) and Nude (2024) strike me as full-frontal assaults on their source materials, Renoir’s The Large Bathers (1887) and Manet’s Olympia (1863) respectively. What is your motivation for taking a revisionist approach to these paintings, which are so important to the tradition of European modernism?

I must confess I find it very easy to attack The Large Bathers. I am not really a fan of that painting, and I wanted to question its position within art history. Painting is an act of mythmaking, and I am annoyed at how The Large Bathers reinforces the trope of naked young women being spied on from a distance. I want to see these bathers in a different light so now they are drowning or trying to survive in a sea of lipstick. With Olympia, I am curious about what remains of a reclining classical nude if I take everything away. In the end, Nude takes on a Cubist tradition. Also, you can see a page number on the edges of Nude because I appropriated a reproduction of the original painting from an older magazine. The colors are a bit off, which made my sandpaper intervention more interesting.

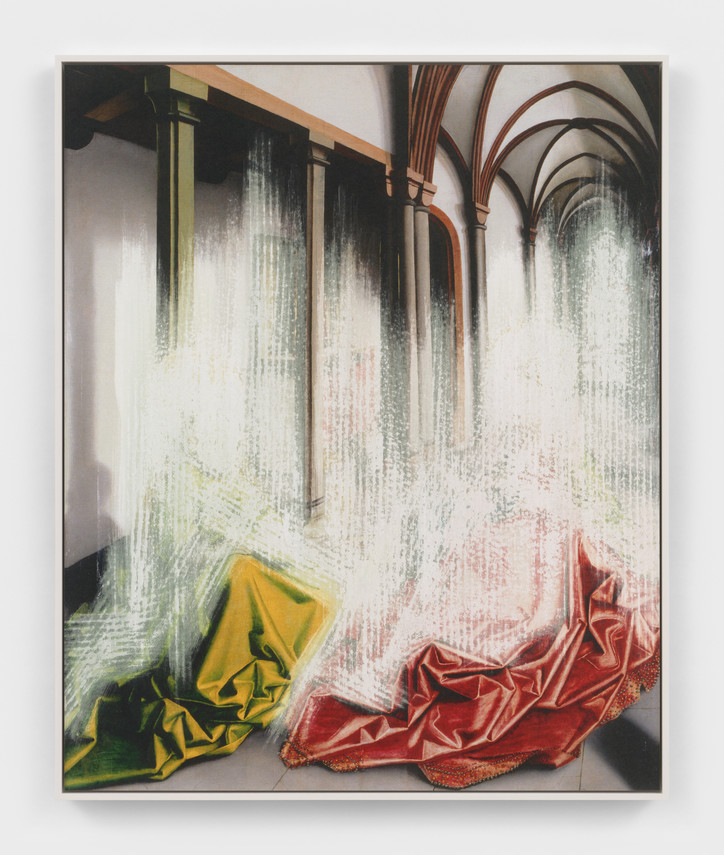

Amie Dicke, Church, 2024. Courtesy of Anat Ebgi Gallery.

Your preoccupation with questions of authenticity and authorship feels most prominent in Church (2024).

Yes, Church is based on the reproduction of a painting I found in a catalog. In the painting, there were two praying figures in a church. I am intrigued by the beautiful, dramatic pleats they are wearing. Once I erase the girls, the pleats take on a very spiritual, almost ghostly quality. In the left corner, you see shadows originally belonging to one of the figures, but now the shadows make the pleats come alive. I was born and raised in a Pentecostal church, so the Holy Spirit is something I am very familiar with.

I read somewhere that your studio is in a church. Is that right?

My studio is in a formerly Catholic church in the center of Amsterdam. I am renting one of the two sacristies next to the altar. The church was secularized but they still have services with another group of Christians on Sunday mornings. Sometimes the church functions as a voting station. Patti Smith performed there too. I sometimes climb onto the altar to find a better Wi-Fi connection. A lot of the days the church is empty, and I am just alone in the building.

Are you still religious?

No, but I still care about the devotional labor in my works. Devotion is very beautiful. I want to be able to train myself to lean into the inner spirits of great literature or painting, and to lean into myself and others. Those emotions and feelings I felt in the Pentecostal church still hold meaning to me. Also, once you have learned how to pray, it stays with you.

I imagine working in a church easily brings out those feelings too.

Yes. Those feelings are everywhere with me. It is more in my heart. Growing up as a young woman in a Pentecostal church and in a very Catholic country, I have always been annoyed by rules and power imbalances within the church. It’s always a man standing there and preaching. Not to mention the Madonna-whore complex. In the Bible, a lot of the female characters are usually sidelined or just presented as a temptress. I want to represent them differently.

Are you then freeing women from the confines of great books and modernism?

I’m not sure if I am freeing them, but I am freeing myself. Maybe at a certain point I will be really free, then I am curious what I am going to make. Too much freedom is panic, right?

You can check out 'Swallow the Lake' between now and October 4th.

How did growing up in Atlanta impact your outlook on the world of art and what it means to be an artist?

Growing up in Atlanta I was only ever surrounded by music. Which is sick because at a young age it was very inspiring to see other people near my age so independent and unafraid to put themselves out there. Looking back now, this showed me that it’s our duty as artists to think outside of the box and to produce new concepts and spinoffs of old ones in order for society to continue evolving.

How do you see your work evolving after this exhibition? Are there new themes or techniques you’d like to explore?

This was just the beginning for me. This show is filled with ideas that I've worked on for about three to four years that I was able to nurture and evolve overtime. As I explored the themes of this show, I found myself opening up the doors to a few new ideas that I'd love to dive deeper on. Now that I have my first studio residency at 99 Canal, I can’t wait to dive in and experiment with more mediums.

There’s a series of prints in this exhibition selling for just $250 each. Do you feel art should be made more accessible to people?

Most definitely. A major part of the show’s conceptualization has been about bridging the gap between multiple worlds. It honestly felt necessary to create something for the younger version of me. The version of myself that didn’t know much about art, but was curious.

Why did you choose to debut in New York and not Atlanta?

I think my background in music definitely played a part in this decision. When musicians go on tour they typically never start in their hometown. My plan is to continue my growth and exploration, so that my homecoming can be as impactful as possible. The contemporary art scene of Atlanta is still very niche, so I’d love to play a significant role in its growth and evolution. I just want to be ready.

What was the last thing you took a picture of?

My baby brother Tana. He’s my favorite subject right now.

Where in the world do you feel most creative?

Atlanta for sure.

Who was the most interesting person you’ve taken a picture of?

Maybe Anok. She’s so sweet and always up to something cool. Frank Ocean was really cool too, we took photos then argued about gumbo.

How do you decide which stories or moments to capture? Is it instinctual or do you plan ahead?

A mixture of both. It really depends on what’s going on in my life at the moment. A lot of my subjects are very well known and are extensively photographed. As I’ve grown, I’ve looked to move away from that oversaturated style of celebrity photography, by moving a bit more selfish in a way. I prefer to show a moment of vulnerability and intimacy, that often feels like a reflection of myself. Most of my photos are self portraits exhibited through my subjects.

How has social media impacted the photography industry, and how do you use it to your advantage?

Honestly it has watered it down in my opinion. Images are now worth less than they were in the past. Everything is too accessible and fleeting. I think we share too much. One of my main goals with my work has been to create a stronger love and respect for photography as a unique art form by creating more physical works instead of just letting my images live online.

Are there any particular subjects or themes you want to explore but haven’t yet?

In my opinion I need to spend more time developing my skills as a painter, but I'd love to explore sculpture and architecture. I have also been doing some digging into my family history and one of my main goals in life is to connect the missing links to my family tree. I would love to incorporate that into my work at some point.

Of the three shows Mulrooney unveiled this weekend, Majić’s is the only one tied to the much anticipated PST ART extravaganza, spearheaded by Getty, wherein 70 museums and galleries between Santa Barbara and Palm Springs are staging shows that illustrate how “Art and Science Collide.” PST curators scouted Majić after his New York solo show “Nocturne” with Nino Mier last year, and asked if he wanted to join the program. Mulrooney is making sure it happens.

I stopped by Majić’s studio near the Jefferson L stop a month before “Dawning” opened, to see the show’s sixteen artworks before they left for California. It had been just several days since his wife had given birth. A sizable, small-scale replica of Megan Mulrooney Gallery crowded the canvases and cacti that line Majić’s studio’s walls and windows, to help him arrange the show.

While “Nocturnes” offered only monumental paintings, “Dawning” marks Majić’s return on the ever-swinging pendulum back to compact creations, which allow him to ride inertia more aggressively — and forge closer relationships with viewers. To call these works paintings doesn’t feel entirely accurate, but that’s how he refers to them. Their surfaces have a sculptural quality.

Motifs reappear. There’s a lone wolf who might be Majić, alongside a captain, a pilot, and an astronaut. Crystal waters pool in secluded spots, and glamorous parties rage in eras impossible to place. Every piece begins with a Photoshop collage. Majić shakes the same box of compositional elements culled from 70s advertisements and Japanese woodblock firework manuals alike. They come tumbling out fresh each time, and he works them over across layers.

Then, Majić draws his scenes on rough burlap canvases in colored pencils. These understudies turn out so vibrant that he finds them “crude,” so he paints atop them. Things get interesting when he mixes marble dust with oil and slathers a milky veil over that base. Next, Majić goes in with colored pencils and carves out flashes of his understudy, toeing the line between vivid and subdued. These surfaces embody the textures he’s portraying, whether that’s water or smoke.

It’s not a perfect formula. “I completely killed the whole image,” Majić says of “The summoning” (all works 2024). “I put so much of that gray layer on it — I was almost crying.” Fortunately, he turned the work around and returned to it as a new person — one who could resolve the work’s wriggling madness into one scintillating pattern. He considers “The inside” the final installment in this spotty story, like a brownout memory. There’s room for error. Is the figure on a couch or a coffin? Rushing water, or a 1980s carpet? In the subconscious, symbols can possess duplicity.

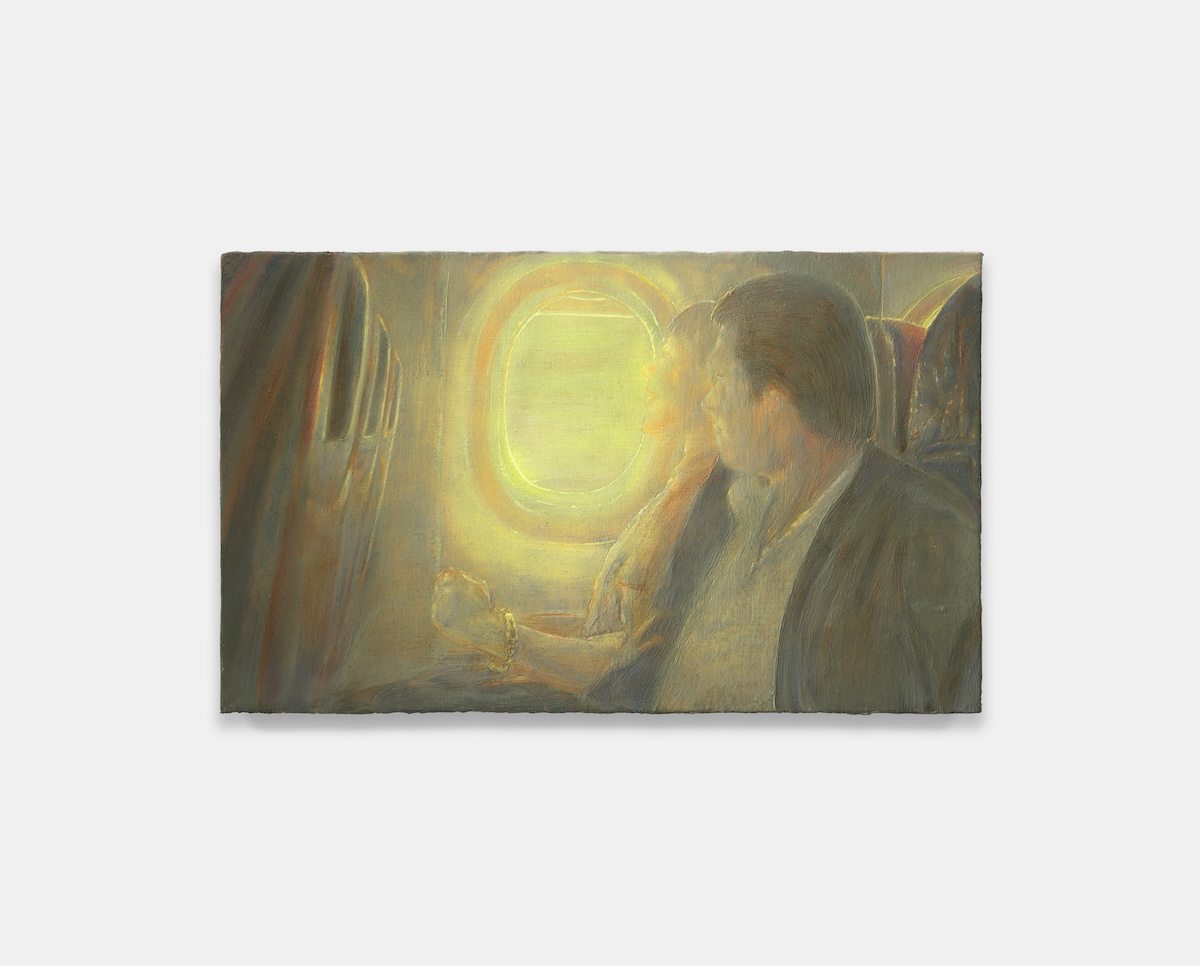

Majić struggled similarly against “You looking for you, me looking for me” and “The Distance,” a diptych that’s separated in “Dawning.” Parties are chaotic, but every detail on a plane is precise.

In the scene on the right, when they were placed together in his studio, a man and woman laugh next to a plane window. In the painting on the left, the man’s mouth is closed, and he’s alone. The plane travels the opposite way. These narrative markers invoke the viewer to invent stories.

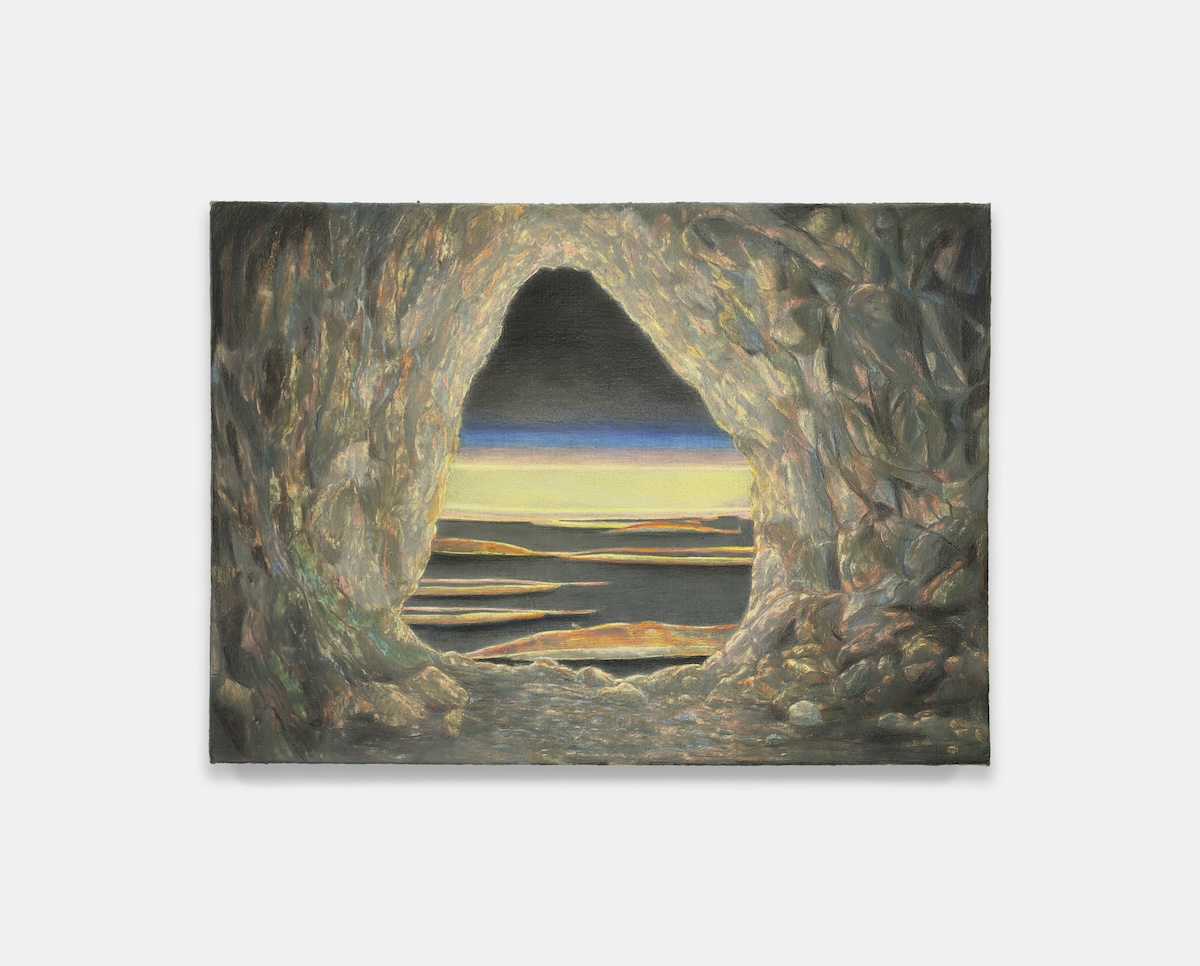

The most potent duo in this series frames either side of the entryway to “Dawning” like a secret little legend. Two cave paintings appear to depict dawn, and dead night. At first, they appear to illustrate a single evening. But, subtle differences between the landscapes beg the question of how much time has actually passed. That’s the trick. This series is really working with time. The sentence “all of these things happening at once” does still describe a concrete amount of time.

Speed dictates time, which stops at the speed of light. There’s your everything all at once. Of course, we don’t typically perceive the real situation. Our animal brains, engineered for survival, filter extraneous details — paring totality down to consensual reality. Not long after art mastered replicating that reality, art began interrogating it, initially through abstract expressionism. Today, it’s through psychedelic ambivalence, like how the orb above “I will not follow” might be a sun or a moon, that calling card of our era. Ambivalence pries the door open, offering entry into a work.

All the scenes in Majić’s latest endeavors could be happening all at once, across any number of places around the world. Such is the nature of consensual reality. In fact, Majić’s dark yet radiant aesthetic, perfectly suited to this moment’s escapist tastes, looks a bit like traveling at light speed. Science hasn’t figured out how to make a person move that fast yet. That’s what art’s for.