The Modern Muse

Stay informed on our latest news!

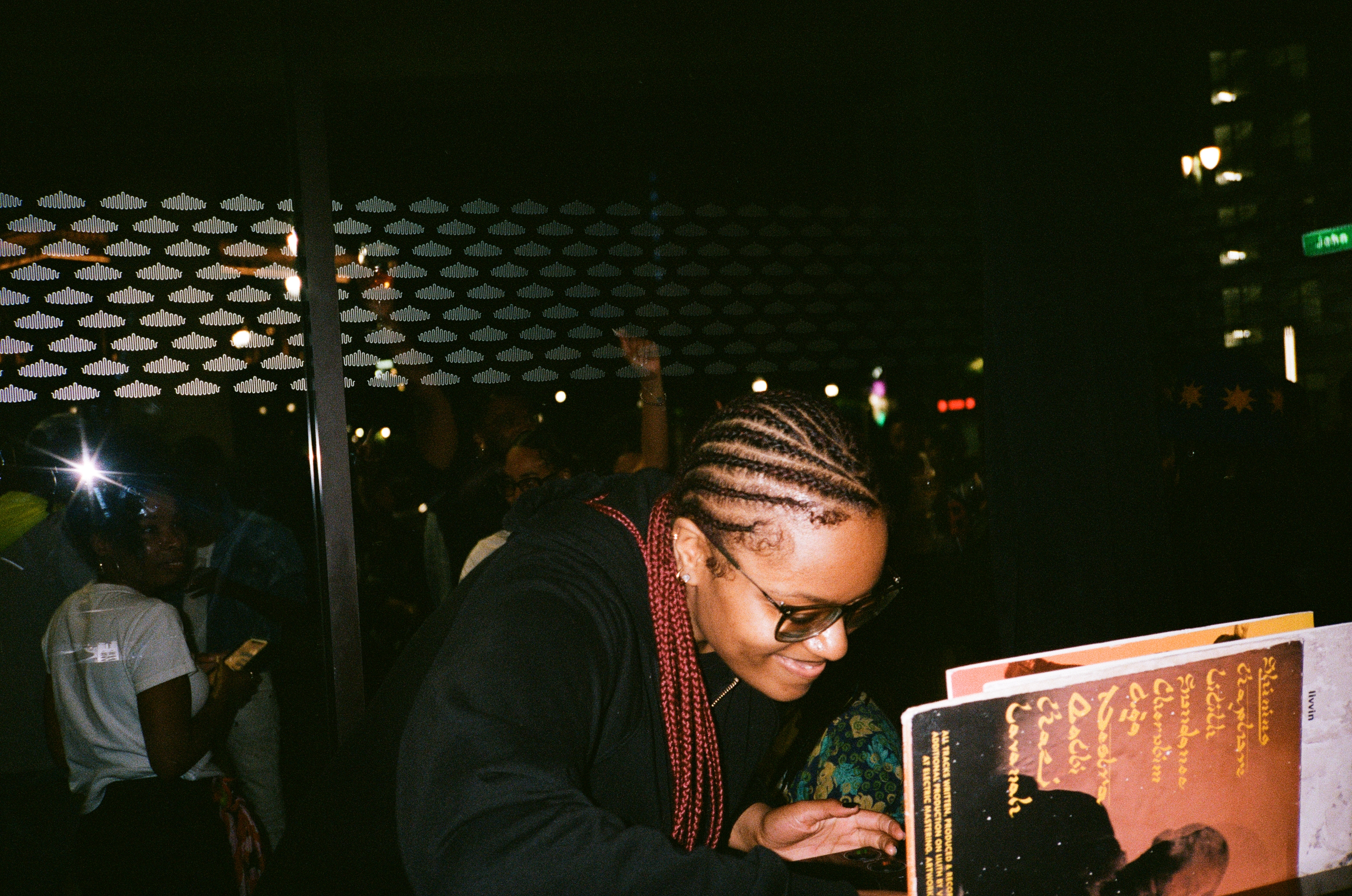

Alpha Industries kicked off the weekend at the hotel’s Ash Bar with a private reception offering food, drinks and DJ sets from WHODAT and Kyle Hall. As midnight approached and it began to wind down, guests made their way next door to the equally notable Paramita, a record store and bar that brought people together all weekend to meet, drink and dance.

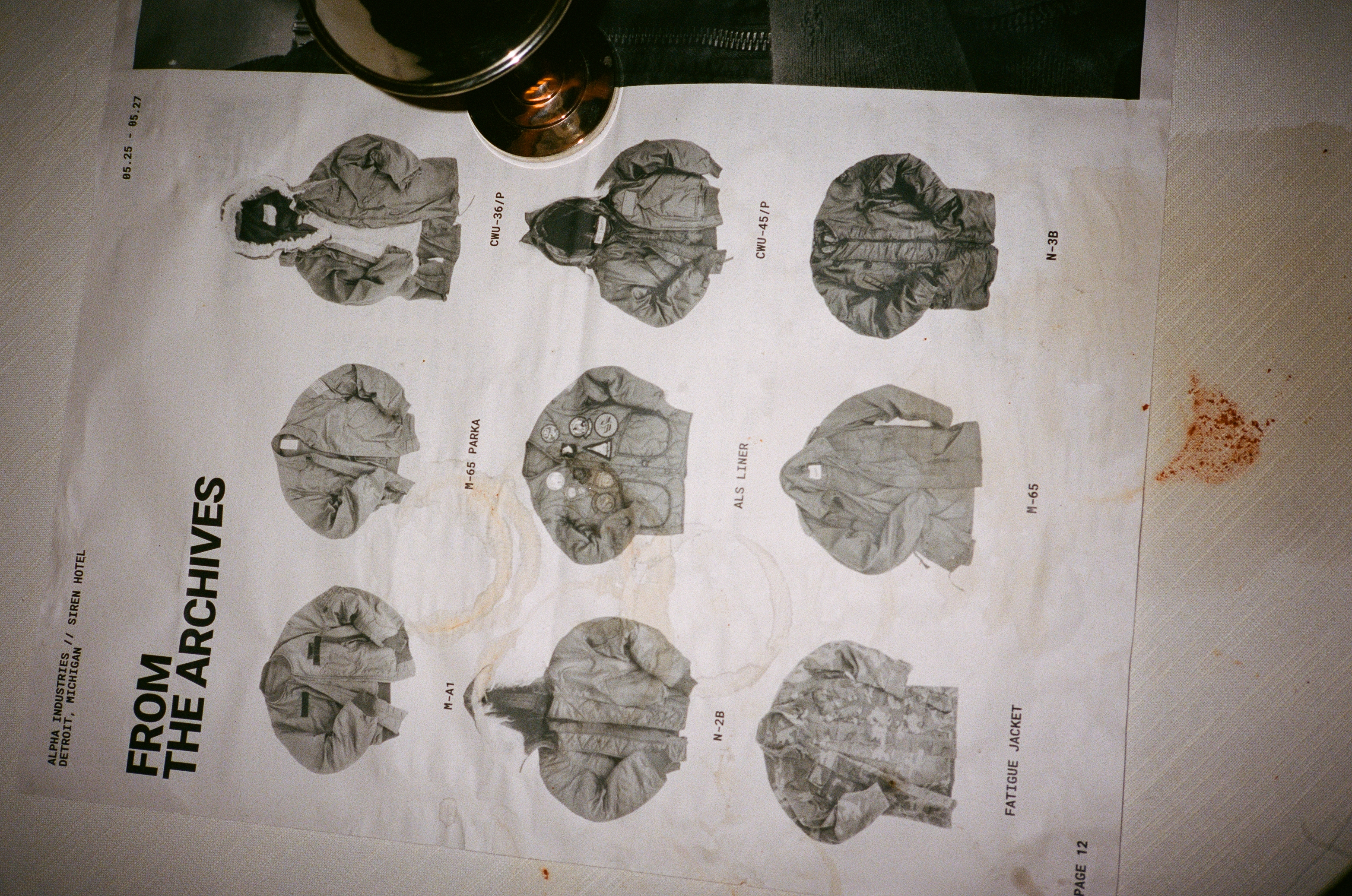

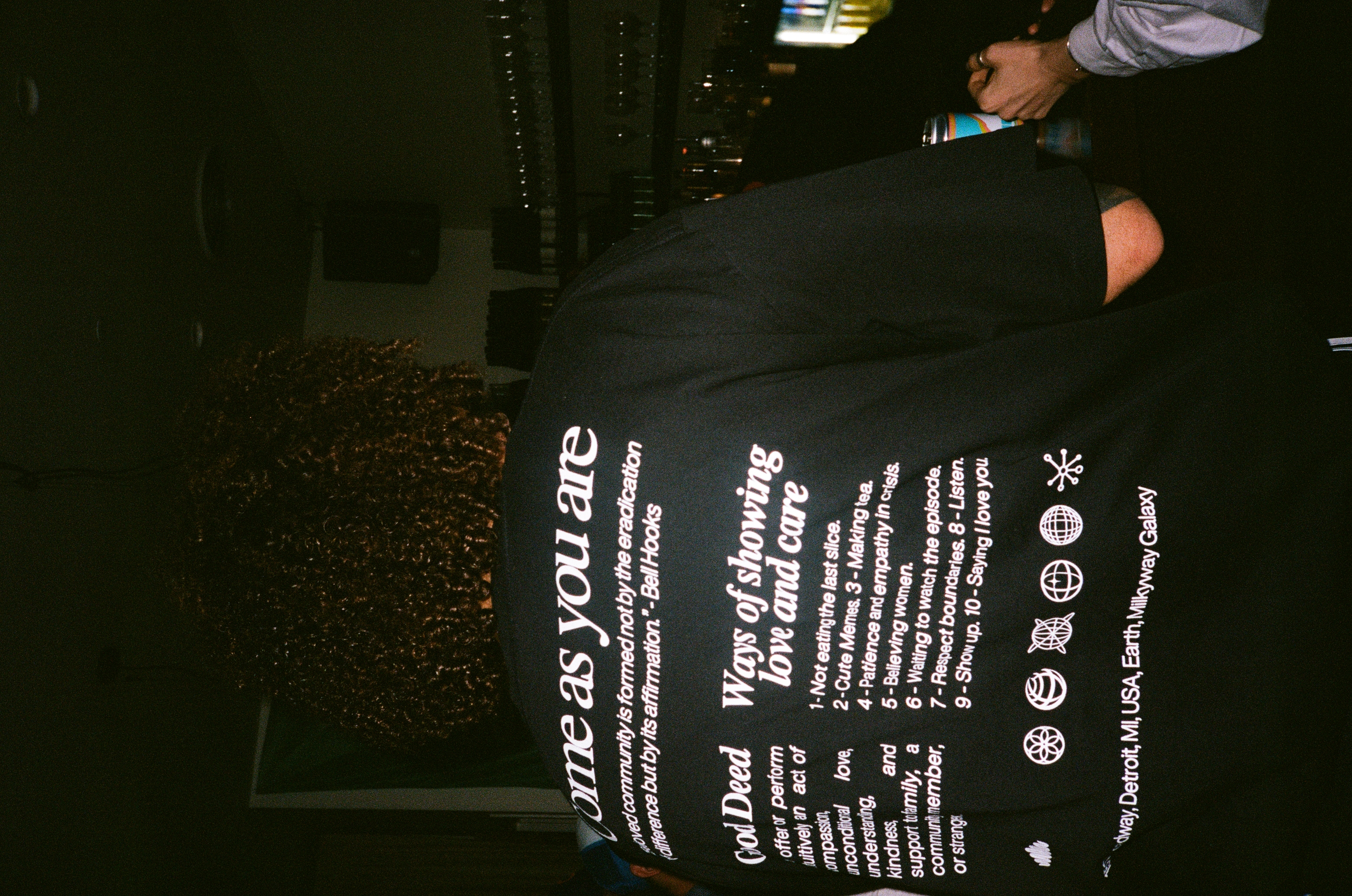

Across the four days, guests and visitors were able to shop from a pop-up experience offering exclusive apparel, accessories and commemorative products. Additionally, Alpha hosted a gifting suite in one of the hotel rooms for talent, guests, and friends of the brand to grab a few pieces from Alpha’s collaboration archive, as well as styles from their most current seasonal collection. Amongst the pieces was their iconic MA-1 flight jacket — a garment celebrating its 60th anniversary who’s origin story began as a practical and functional garment for pilots in the United States Air Force and Military but was uniquely adopted in the 70’s and 80’s as an emblem of youth culture.

The parallels between Detroit's music scene and Alpha Industries' cultural impact are unmistakable. Techno music was once considered the epitome of counterculture and an underground convergence of music, art, and fashion; the same subcultures that embraced Alpha Industries as a staple brand in the rave scene — worn by punks, skaters, and hip-hop artists.

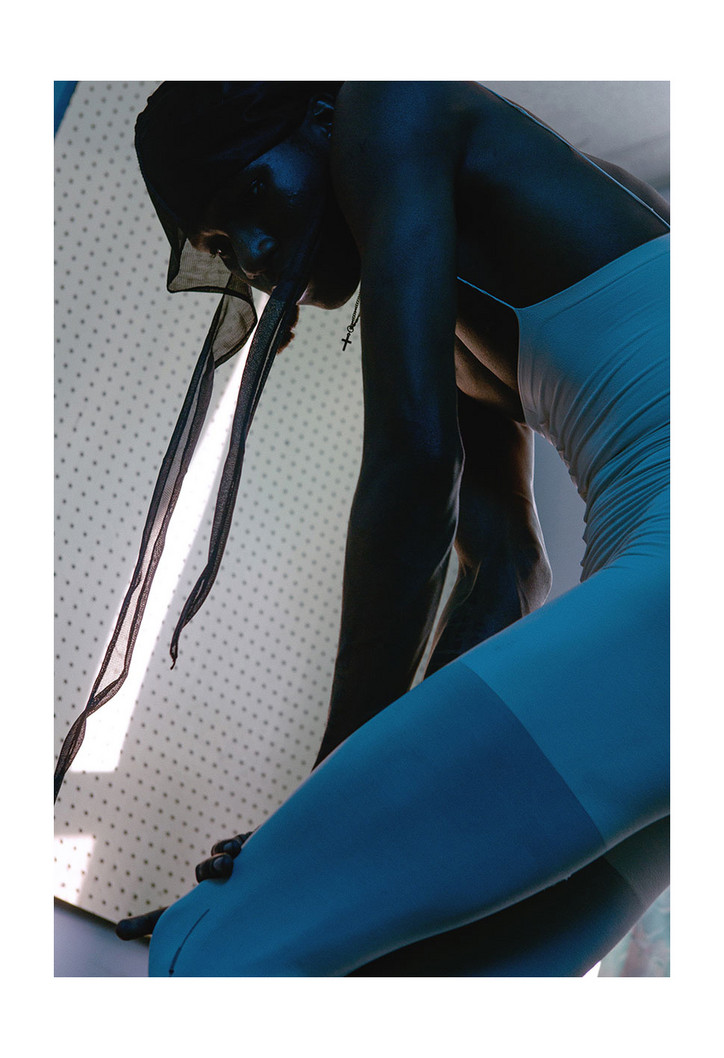

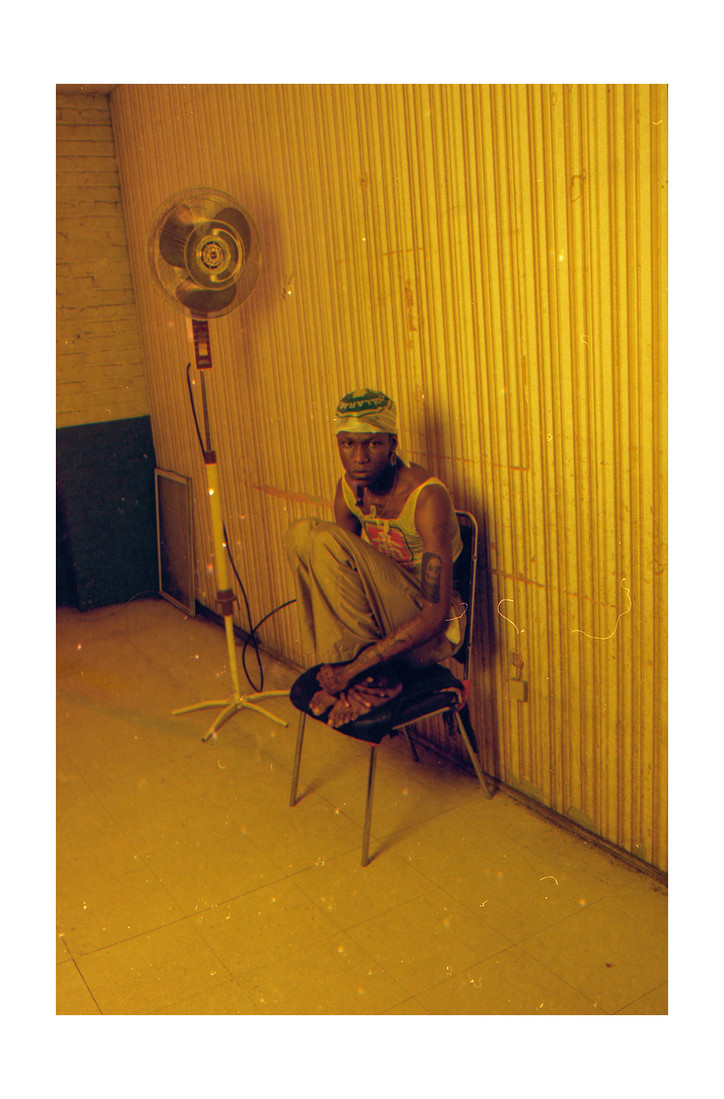

Take a look around Detroit and Movement Festival below.

It was my first time at Winona's. I brought along two friends who live within walking distance. They hadn't met before, but one being Armenian and the other Lebanese, they immediately bonded over the menu, sharing memories, and eventually coos as food arrived on the table. For Nadia, "food is the purest, most direct path to someone's heart." A shared meal can bring people together. The dinner series achieved just that, while offering a new perspective on the Israeli occupation and genocide of Palestinians in Gaza. The deep connection between the Palestianian way of life and the land is evident in every dish, countering the frequent appropriation and misnaming of traditional Palestinian cuisine.

Reflecting on the growing curiosity about Levantine cuisine, Nadia considers "how our people are so focused on preserving tradition, with many forces trying to erase our people and our culture, even giving our food another name." She's "interested in what happens if we are not needing to preseve and protect first, taking traditions and applying them to new ingredients or creative ideas." Nadia introduced Pierce to this idea of 'future palestine', a menu beyond borders where her heritage and Pierce's Armenian's roots could intermingle, creating a "sliver of a moment where we start to imagine what a liberated future could taste like."

Over Memorial Day weekend, Pierce called Nadia up to discuss the first meal they shared, Nadia's idea of 'future Palestine', and the deep connection between the Palestinian way of life and their land.

Pierce Abernathy — Ever since you first had us over for dinner about a year ago, I immediately fell in love with your food. It was so delicious and so nourishing. You made a salad with eggplant and yogurt similar to the beet one, maybe with walnuts, I can't remember, but it was so addicting. I couldn't stop eating it and it was so special.

You know, I love doing these pop ups because I love to engage with a community, and one of the reasons I love to cook is I love to show love and to share in that way, and you can't really do that online. As Tin and I were talking about doing this, this being such a community-focused thing for me, I really wanted to work with different people in the community, and we immediately thought of you — I was so happy that we made it work.

Nadia Irshaid Gilbert — Oh man, me too. That warms my heart so much. I love that that dinner was memorable to you. That was so special to me too, having such good people in the space and being able to cook for y'all. I was so honored and excited when Tin reached out about the tour this year. I love how the tour has expanded and evolved this year and that you’re bringing in more people. I want to know what the personal significance of this one was for you?

I'd say that, for me, food is one of the greatest and easiest ways to connect and understand and learn about a culture and with the genocide happening in Palestine, people are seeing so much destruction. Having an opportunity to collaborate with you and learn about your perspective on the food as your vision of the future of Palestine was such an interesting way to explore and learn and educate myself around Palestinian culture, food and history. It’s a great way to do something for people beyond raising money — nourishing, and a way to better understand Palestinian people through their dishes. I find that to be such an eye opening experience, and I feel very lucky to work with you and to be able to help deliver that experience to people.

Yeah, it was so beautiful. And I completely agree, I express that a lot — food is one of the most direct and easy ways to access somebody's heart. Sharing a meal, consuming the same thing together, especially when a lot of love was put into it with your hands is one of the easiest ways to get on this mutual level with people simply as beings that need to nourish themselves. Returning to that single primal human need together can carry so much significance. It's such a powerful medium to work with and to share with people, especially when served with the intention and invitation for people to look deeper and connect with each other beyond the surface level. I feel like we were able to provide a space that invited that, allowing people to connect and imagine something new together.

Yeah, absolutely. I think when you're making people food, there's this inherent vulnerability that you're sharing, as in, I have the confidence or the desire to nourish you in this moment. And at least from what I've seen, what I really love is people who are eating, who are being nourished, understand this vulnerability and open themselves up to this vulnerability, whether it's through conversation or the experience. There are conversations that can happen at dinner that wouldn't be able to happen anywhere else. There's something about that experience that opens people up in such interesting ways, which I love. That’s addicting in its own way, whether I'm cooking or whether I'm eating.

Totally. There's this softening that happens when you share a meal with people, and that's often taken for granted and not utilized to its full potential. That's something that I think is really exciting when you can, especially at a moment like this, where there's just so much misunderstanding and polarization. When you can gather people and nourish their souls and teach them through that and enable them to teach each other, that's really something powerful.

I would love to know more about how you came up with this menu, and this idea you talked about of ‘future Palestine’.

It really started from a place of wanting to operate in a hyperlocal, hyper-seasonal way. I feel like that’s a value that we both carry in how we like to cook and the way that we like to interact with food and serve it. It’s really the future — we both understand that returning to the land and connecting to the earth and the local environment through what we eat is an important way of being. And that's also inherently a Palestinian value because Palestinian cuisine changes depending on what is in the immediate area... working hyper-locally and in-season is a way of connecting with the heritage of living off the land.

Then, this idea of future Palestine came from this sense that people are becoming more and more curious about the cuisine of the Levant and what it looks like. I wanted to give people an experience that was different than what they would expect to see, dishes that highlighted what was really shining from the land at this moment. When I think about 'future Palestine', I think about how our people are so focused on preserving tradition in light of so many forces at work trying to erase our people and our culture, even giving our food another name. I’m interested in what happens when we don't need to preserve and protect first, free to imagine new possibilities, taking traditions and applying them to new ingredients or creative ideas. Also incorporating some of these Armenian flavors, breads, dishes, and pieces into the meal is part of that because I believe the future is not so strict and full of borders, but rather borderless, allowing us to mesh with each other because that's what's happening globally anyways.

Yeah, that's so powerful. You make such a good point, this idea of reinventing cuisines is such a luxury, and it's something that certain people take for granted with Palestinian cuisine. I was speaking with this other Palestinian chef who mentioned wanting to create a cookbook filled with traditional Palestinian recipes. He's been going around talking to all of these grandmothers, trying to preserve the history of these recipes so that they don't change. As much as we want to reinvent and look forward, I'd say that it's as important and maybe even our inherent responsibility to preserve and protect, and you did such a great job with the menu, putting your own spin on a lot of these classic dishes.

Well, thank you. I don't know if the word is balanced, but that reverence for our ancestry and honoring our past while integrating it into what we create in the future, that's where magic happens. That's where we innovate, not to make something better, but to allow ourselves and our unique experiences to shine through in what we create and the way that we communicate a message or connect people through food. That's where the present of who we are actually comes through and something really beautiful can be created.

I feel that so much. Ever since I received my great aunt's cookbook, it's been one of my most sacred items, and it's something that I've thought about so much. I would love to republish it and share my own takes on the recipes, side by side with the original recipes. And yeah, I think what you said is so powerful. We have to look forward and we have to look back to be right here in the moment.

You all gave me a lot of creative freedom to start a summer with the menu, which was such a gift, so freeing and exciting, and I loved everything that you introduced. I'm wondering what influenced any of the choices you made.

I really wanted this to be your moment. I was happy to jump in and help as much as possible, but really wanted to give you the creative freedom.

As we started developing this first dish, A Taste of a Land, I became really obsessed with Armenian string cheese. I made this variation of marinated string cheese on last year’s Spring tour as well and it's become a staple in this rotation when I do some events. I didn't really eat it too much growing up, but as I started to learn more about it, I was talking to my grandmother who's Armenian, and she told me this story that she, her sisters and brother would sit around when they were kids and unravel the string cheese, competing to see who could peel the thinnest string cheese. And I just loved that. It was like a game. The day before our first night, three or four of us spent three hours sitting at a table peeling string cheese. There’s something so funny and young and nostalgic, even for people who haven't had it before to do that. The spices that I marinated the cheese in are very much flavors from both Armenian and Palestinian cuisine.

Then of course, bread is such an important staple in the Levant, it’s at every meal, and everyone knows how to make bread. We were building this menu around love and sharing this part of ourselves, and for me, there's something really special about making homemade bread. One of my recent favorite dishes is this herb stuffed flatbread called Jingalov Hats. Two dishes that feel nourishing and are a great way to start a meal.

Yeah. Oh man. I loved that moment when you were all sitting around a table chatting and pulling string cheese. It was a beautiful little familial moment, and it was so sweet. I feel like it captured the soul of both of our cultures in coming around a table together and taking your time preparing something with your hands and with love. I love that first dish too. It was such a beautiful marriage of our cultures, showing the parallels in the ways that we eat and the ways that we use our hands and interact with food to connect with the earth.

One dish that I couldn't get over were these damn chickpeas that you made. I am someone who loves simple food, and I was so blown away by the flavor that you brought out of what I'm assuming and what I saw was such a simple dish. Can you talk a little more about that one?

Yeah. That dish is a relatively new one for me to make, but it is really similar to a very iconic Palestinian dish called Musakhan, which is chicken marinated and cooked with a lot of sumac and caramelized onions. It's this really bright taste of sumac that is so iconically Palestinian, and it's served in a very similar way. When I recently learned about Sumakkiyeh, which is this chickpea and lamb stew — Sumakkiyeh really just means it's a sumac stew, and you really highlight that bright citrusy flavor. There's something really nostalgic about it and I love its simplicity because it's really a dish of the people, especially because you can make it without meat. When meat’s very expensive but you have sumac, it's a dish that is accessible really to any people. And I think it is just something I love to make both to honor the people of Gaza and also to honor the kind of innovative simplicity that Palestinian food often has. And I'm so happy that it turned out so delicious and that you loved it so much because it's also my hands and my love going into the dish with simple ingredients and good sumac. It's allowing the ingredients to speak for themselves that makes it so special.

I’m also curious to know how you’re feeling more generally after the experience.

My heart is feeling so good and so hopeful after this experience. I think it's so meaningful to do something like this with such a wonderful group of people who really care and have such good hearts and the determination to create such a meaningful experience for everyone who came. Also the support that we had and the way that we were able to just gather such cool people who are all out for Palestine and for this idea of possibility and liberation meant a lot. Experiences like this are very, very meaningful to me, and it was truly such a gift to work with you and this team to create just a little sliver of a moment where we start to imagine what a liberated future could taste like and what's possible when we don't have these walls between us. I'm still all mushy from the whole thing.

Yeah, me too. There were just so many moments. I was there at service, seeing you and the energy that you were giving and all the tables you were talking to, and I felt overwhelmed with emotion in such a positive way. The menu really reflects everything that we've talked about. I'm just super happy that you wanted to work together, and I hope we can continue to in the future. Experiences like the last two days are really why I love to do these pop ups, and I couldn't have asked for a better one. Thank you.

Thank you. And inshallah, more to come. It was so much fun and makes me excited about what else is possible.

Yeah. Okay, well enjoy the rest of your lovely Memorial Day weekend. I'm glad we got to get a little emotional on this Sunday, and I can't wait to eat more of your food.

Oh man. Me too… And thank you.

Of course. Okay, enjoy the beach.

Thanks. I will. Enjoy LA. I'll talk to you soon.

Take care. Bye.

Part of an emerging movement in France — a new existentialism that turns its gaze on all of existence rather than on the human perspective — Schultz was a close collaborator of the late French philosopher and anthropologist Bruno Latour, who championed this ‘nonhuman’ idea. Their co-authored work, On the Emergence of an Ecological Class: A Memo (Polity Books, 2023), translated into 12 languages, provides a blueprint for constructing a political subject poised to advocate for the planet’s habitability. Praised by scholars like Dipesh Chakrabarty, Clive Hamilton, and Slavoj Zizek, Nikolaj’s recent book Land Sickness is a hybrid text that revisits the human figure and engages with the sociological and existential questions that the Anthropocene forces us to pose.

Newspapers have crowned him “the coming star of sociology,” and similar to Latour, his influence extends beyond academia, permeating the art world and inspiring artists and curators such as Fontaines D.C, George Rouy and Hans Ulrich Obrist. Before his passing, Latour introduced Nikolaj to Hans, but it was last summer, prompted by Corinne Flick, that Hans delved deeper into his work, picking up Land Sickness as his summer read.

Hans has played a unifying role in the art world, cultivating spaces where people, perspectives, and ideas intertwine. As the artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries, he has curated numerous exhibitions and projects that engage with environmental issues and sustainability. Additionally, he has promoted eco-conscious practices within the art world itself, leaving a lasting impact on the way contemporary art addresses ecological challenges. In October, he invited Schultz to give a talk at Serpentine’s prelude to this year’s Infinite Ecologies Marathon, which explores this new perspective on our relationship with nature, redirecting our attention to the world as it is rather than the human-centric one we’ve constructed.

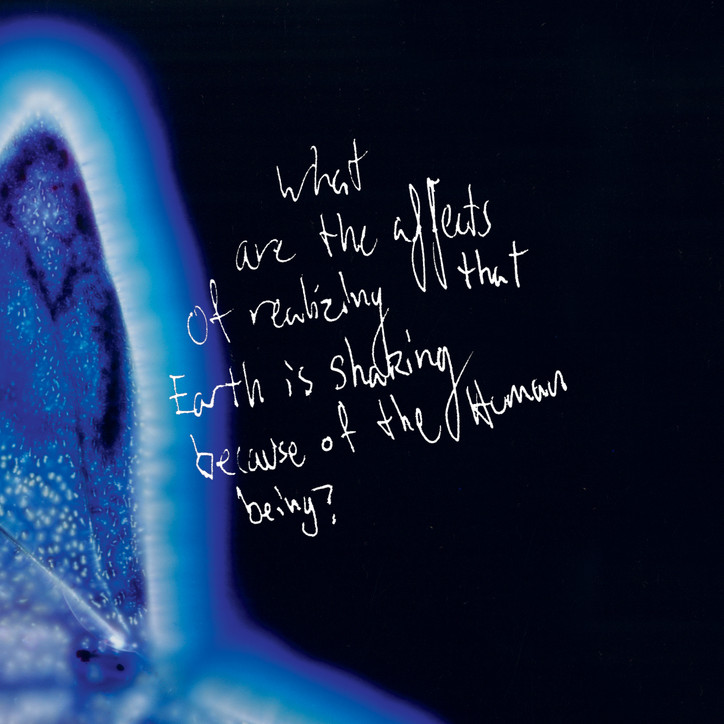

A few weeks after our initial meeting, I managed to arrange a call with Ulrich Obrist and Schultz — a feat in itself — to discuss Land Sickness, the Anthropocene, and this new Earth “shaking beneath our feet.” Nikolaj's hand-written quotes shared throughout this article are inspired by Ulrich Obrist's Remember to Dream! 100 Artists, 100 Notes, a collection of "thoughts for the day, dreams, drawings, musings, jokes, quotations, questions, answers, poems and puns" handwritten on Post-it notes (and other scraps).

HANS ULRICH OBRIST — In this age where information is abundant but memory often falls short, I think it’s important to acknowledge the artists who have contributed to the discourse on the climate emergency since the start of the movement. In my field, Gustav Metzger springs to mind, who has been at the forefront of this struggle since the 60s/70s really. Then there’s Agnes Denes, whose seminal 1969 manifesto resonates powerfully today. And the Harrisons who contributed a manifesto that criminalized plastic for our ongoing Back to Earth program at Serpentine. There are all these artists in my field, so I’m curious, Nikolaj — who do you see as the pioneers in your field?

NIKOLAJ SCHULTZ — As you know very well Hans, the discourse on our ecological problem stretches back to mid-century movements, like Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962 and the ‘Limits to Growth’ report in 1972. Yet, my field of social theory was relatively late in developing a conceptual language for discussing these changes — even if you can, of course, find ecological “undertones” in modern social theory. For example, in the work of one of my heroes Karl Polanyi who perceptively intertwined social relations with environmental conditions in his analysis of societies. There has been more progress in recent decades, thanks in part to thinkers like our common friend, Bruno Latour, whose seminal work reintegrated nonhuman actors into social theory. Also led by figures like Timothy Morton, Donna Haraway, Emanuele Coccia and Anna Tsing, among others, this shift in thought has illuminated the agency of wolves, spiders, octopuses. Latour in particular helped bridge these ideas into the art world, which you’ve also been instrumental in doing.

HUO — I think that to properly tackle the significant challenges of the 21st century, we need to overcome the fear of sharing knowledge, so throughout my work I’ve aimed to do just that by bringing people together. I see curation as I do it as a form of “junction-making,” as J. G. Ballard once described it to me. I’ve created events like Serpentine’s Marathon and exhibitions like Laboratorium, Cities on the Move, and do it to serve as vectors between people and ideas.

When I first met Bruno, he felt undervalued in France at the time, particularly by its institutions, so I invited him to collaborate, together with Barbara Vanderlinden, on what we named “Laboratorium”, which looked at the workspace of artists, the studio and the laboratory as a kind of network. He was hesitant at first, but his involvement turned into enthusiasm as he organized tabletop experiments together with Peter Galison, Caroline Jones, Panamarenko, Rem Koolhaas, and Isabelle Stengers — who made the private practice of experiments a public affair. And of course, the actor-network theory was kind of crucial for that.

It all grew out of us bringing people together. You of course worked even more with him and were really the person he was most interested in as part of this younger generation of sociol - ogists, so I’m eager to hear how that came to be and about this book you co-authored before releasing your own.

NS — I first crossed paths with Bruno when he was my teacher at Sciences Po in 2015, engaging with his course on the philosophy of nature, which later influenced his seminal book Facing Gaia. For some reason he found me a good student, so slowly, in the following years, we started exchanging ideas about this new Earth that had begun shaking beneath our feet. These exchanges turned into a real collaboration around the time he was writing Down to Earth, in which he introduced the term ‘geo-social classes’ that we would collaborate on until his death.

As a sociology student who — before I encountered Bruno’s thought — had been trained in the old German tradition of critical theory, and in Marxism to a certain degree, I thought that this idea of a new concept of class for a time of global climate change was interesting. And knowing that Bruno tended to sometimes not follow through entirely on his many conceptual inventions, I pressed the case that we should take this newly minted term seriously and develop it further than he had done initially.

This we did, then we began writing our book on the topic in 2021, analyzing why ecological parties struggle to gain political support despite the overwhelming evidence of the unfolding ecological disasters. Our book, on the one hand, sought to diagnose this void in political effects, the absence of mobilization and lack of political passions for ecology — and on the other hand, it tried to indicate pathways out of this political inertia.

We argue that ecologists haven’t taken the cultural struggle for ideas seriously enough, and art plays a significant role in this struggle, capable of shaping our sensitivity for issues previously ignored and driving social change. Bruno was heavily inspired by your work in this regard, an insight that followed him for many years, all the way up to his last book, On the Emergence of an Ecological Class, the one he and I wrote together.

HUO — That’s exciting. I read the book in German. You mention movements like Fridays For Future and local organizations working locally and nationally, drawing a parallel between historical workers’ movements and the present need for an ecological class today to halt climate change. Yet, you advocate for a politics that broadly protects our Lebensgrundlage — our foundations of life. It made me think about Joseph Beuys and a lecture he gave in Rorschach, back in the ‘80s when I was still a child, about his role in co-founding the Green Party. He was an artist aiming to marshall this ecological class you refer to. From your perspective, what are the practical steps we can take to move beyond the book and into societal action?

Nikolaj Schultz by Jesper D. Lund

NS — We were really bemused by the dispersed nature of the climate movements, with little action despite looming disasters, which we see unfolding in front of our eyes. Why are “We” not acting? Well, our argument is that nobody really knows who this “We” consists of.

The past half-century, the ecology movement has squandered precious time, sustained by the belief that as ecological disasters loomed closer, people would naturally rally under the banner of Mother Nature — that a common recognition of our shared planet would unite us in action, all together. Instead, these questions of nature, soil, land, territory are not topics that unite us. We all see that now, in every country, all over the continents. Ecology is not a peace treaty; it is rather to be understood as a battle cry.

However, these conflicts are not the Achilles heel of ecology and political mobilization for the climate question, they are actually its unrealized potential. We are witnessing a strange historical reversal, where it is exactly the process of production that has turned into a system of destruction that threatens ecological sustainability. The issue now is connecting these conflicts into a unified narrative, which could help to create a “We” relative to the nature of today’s conflicts. As social history has shown, embracing conflict can be beneficial in galvanizing political movements. While it’s not fully formed yet, we see examples of this emerging ecological class fighting for the planet’s habitable condition worldwide — for instance, indigenous people in America fighting for their territory, others fighting against the construction of polluting coal-mines in Germany or against mega-bassins in France. We are also seeing inklings towards making it a consistent political narrative. The big problem is of course that historically — as you know — the evolution of a class consciousness typically unfolds over a century, a timescale we simply don’t have. If we’re to stand a chance, paradoxically, it is essential to embrace a slower pace of trying to construct such a thing, and art plays a vital role in this process.

And for good reasons, because imagine what Frida Kahlo did for communism, what Goddard did for socialism, or what a writer like Jack Kerouac did for liberalism. The arts intrinsically demand time, and it is because we are in a hurry that we must take ours, as Bruno used to say.

HUO — That’s really interesting. In your talk at the Serpentine in October, “On the Many Ways of Becoming Sensible in the Anthropocene,” you discussed a new existentialism for our era, focusing on our changing relationship with non-human entities — calling for a greater sensitivity towards all life forms. You emphasized the need to not just analyze this shift but also describe how human existential conditions are changing in the Anthropocene—evolving into an entity that threatens its own species and its habitats. Can you elaborate on this idea? You hinted at it earlier, but I’m also curious about how spirituality factors in.

NS — The point I made in the Serpentine talk — and one I still hold firmly — is that perhaps while we’ve made many strides in considering non-human life that pushes back against centuries of anthropocentrism, we also need to understand how human existence is changing. For me, a new existentialism needs to include both. Today, to be a human being means understanding that you are a species that is in the very middle of destroying its own conditions that it needs to sustain its life.

Think about it this way: Over the summer, the film Oppenheimer captivated many, and for good reasons, because it marks an interesting turn not only in world history, I would argue, but also in the very existential conditions of the human being. Karl Jaspers explored this in The Atom Bomb and the Future of Man.

Back then the situation was different, because it was simply a few political or military elites who held this power of extinction. But today, we collectively hold the power to harm our species with everyday choices — taking a shower, drinking coffee, traveling by airplane. We’re all, in a sense, constantly echoing Oppenheimer’s words, “I have become death, the destroyer of worlds,” because of the destructive traces that we leave behind.

This idea of a new existentialism fit for the New Climatic Regime is what guides my investigation in Land Sickness. What interests me is the emotional-existential and psychological-moral landscape that this creates: what are the effects, the feelings, the experience of understanding that you have become a creature that contributes daily to the slow destruction of its own species’ conditions of existence? What is the confusion, the nausea or the vertigo, to speak the terminology of the old existentialist Sartre, that this creates, when you are realizing you live on a planet that is shaking because of your own actions?

HUO — This is the central question you raised at the Serpentine.

NS — Yes, exactly. I raised the question of this new human conditions’ translation into art, and the artists you highlighted at Serpentine that day have of course begun this work, largely turning their creative focus towards the non-humans that we coexist with — like your friend Tomas Saraceno. I wonder if there could be a new artistic gaze towards the new human condition in the Anthropocene. Have you noticed any signs of this in your curatorial practice or elsewhere in the art world?

HUO — I feel like there’s a strong appetite today among artists to break free from the event culture mold that most exhibitions, even long-standing ones, fall under. We see more artists who wish to question and reinvent the fundamentals of what an exhibition can be, like Tomas, who transformed a gallery with solar panels and visitor-pedaled bicycles, giving space to non-human curators like birds, spiders, and dogs. Meanwhile, artists like Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg take a different path, opting out of traditional shows to create AI-assisted gardens for pollinators — a space enjoyable for humans, but decidedly not for us.

There are also long-term projects, like a farm and artist residency in Nigeria developed by Yinka Shonibare, inspired by Roman Krznaric’s ideas on deep time from How to Be a Good Ancestor; and thinking about how art can catalyze environmental campaigns, which led us at the Serpentine to compile 140 Artists’ Ideas for Planet Earth, a collection of practical instructions from artists on how to engage with ecological issues in daily life.

Returning to your book, Land Sickness, there’s something truly captivating about it. It pulls the reader in but not in the way a typical theory book might; it’s deeply biographical and experiential, naturally making it existential. Once I started reading it, I found it impossible to stop.

The way it commences — with the relentless nature of our problems. The sense that there is no escape stays with the reader. It follows you in the same way that these problems do and while it reflects your personal journey, it also resonates as a collective narrative.

It clearly aims to reach beyond an academic audience, reminiscent of Bruno’s evolution, his profound leap from scholarly to mainstream thought, now being one of the most read philosophers globally. You seem to be following a similar path. How did you approach writing with a broader audience in mind?

NS — When I was writing Land Sickness, Bruno was penning After Lockdown [called “Where am I?” in French]. We were both starting our drafts during that same awfully hot summer, sharing them back and forward. Bruno was asking “Where am I?” But I suggested asking instead “What am I?” — exactly because this “what” today is intrinsically linked to the question of “where”.

And now, my attraction to this question — and especially because I was interested in the affects of this transformation — led me to write in a different style, one that bridges the academic and the affectual. I did not know that I would write a full book in this tone before I saw the impact it had. Land Sickness actually started as a short essay that I published in a few different languages. I was surprised to see how it garnered attention from people both within and outside academia, so I expanded it into a book — one that falls more into the category of “literary sociology” or “literary existentialism” than “existential literature”.

With certain existential questions, and with the experience of a self or a subject changing shape, it can be useful to start with our own experiences, hence the awfully outdated “I”-narrator. Classic existentialists did this too. And I think, if the reader approaches the book as a hybrid essay as I describe, then it might perhaps resonate. I hope that it does, because related to our discussion above, the Anthropocene and our New Climatic Regime demands new ways of narrating theory, because as Ursula Le Guin once suggested, we need both the curiosity of science and the risk of aesthetics. And this is the path I tried to aim for in Land Sickness, by finding a genre in between.

HUO — When I first met Umberto Eco in Milan, we had a conversation and then after, he showed me his incredible collection of old books. In his apartment, he had a locked room full of medieval manuscripts that only he could enter, like something out of his novel The Name of the Rose. As I was leaving he asked me, “Do you people still hand write?” He then said that handwriting is disappearing and that he is too old to do anything about it. That is the task he gave me, to help save handwriting from extinction.

At that moment, I wasn’t sure what to do. I couldn’t just start a calligraphy school, I’m not competent for that. However, a few weeks earlier, the artist Ryan Trecartin had just introduced me to Instagram. And one rainy day soon after, I was sitting in a cafe with Etel [Adnan] chatting.

As everyone looked at their phones, she wrote a poem in her notebook, which is when it clicked. I meet artists and poets all the time. So, I started to ask them to jot down sentences whenever I met them, which led to Remember Nature, and then what’s become somewhat of a movement on Instagram, protesting the death of handwriting.

One of those sentences was yours, beautifully put: “We are all suffering from land sickness. The earth is trembling and the human is trembling with it,” which reminded me straight away of Édouard Glissant, who was like a mentor to me. He always talked about a ‘trembling’ world, a utopia in constant motion. I’m curious how this idea has influenced you and how it’s significant in your work. Can you elaborate on what a “trembling utopia” means to you?

NS — I will have to read Glissant now, and — this is probably the one and only time I will ever say in an interview that I am a patriot, and that’s because when I think of “fear and trembling,” I am of course drawing directly on Kierkegaard, a fellow Dane!

Yet, again, there is a difference. Kierkegaard was describing his anxieties, his anguish, but his answer was related to a deep and thorough exploration of the inward depths and freedoms of his subjectivity. But what struck me, while I wrote this note to you at the Serpentine, is that today, the trembling is different: Today, if we “fear and tremble”, it is not because of a dizziness that comes from realizing the limitless possibilities of your own subjective freedom. Instead, it is a dizziness and a trembling that comes from the ruinous traces that your freedom has left behind, which swing back at us like a boomerang, threatening the limits of the Earth System and the planet’s habitability.

HUO — This was one of the main topics of our project Back to Earth.

NS — I want to touch on the short yet fascinating book project of yours, 140 Artists’ Ideas for Planet Earth, which underscores an important point about the need for closer ties between artists and political movements, particularly those focused on the environment. Bruno and I have critiqued the lack of such alliances as it’s not about artists or curators falling short but rather about political ecologists not fully embracing the potential of creative initiatives like yours. How do you see the political realm engaging with and embracing these questions and resources?

HUO — I believe we’ve reached a time when every organization, whether it’s a political party, a government, a corporation, or a brand, should include artists in their decision-making processes as artists John Latham and Barbara Steveni suggested through their artist placement group. Artists adapt quickly, which is crucial for tackling issues like climate change.

What once seemed like a utopian ideal for companies is now really a necessity. A decade ago, when I mentioned this concept to CEOs and government officials, they’d laugh it off. But now, it’s not a joke anymore; people are taking it seriously and asking how to make it a reality. However, fully integrating artists into these sectors is still a work in progress. The idea of bringing artists in all these sectors is still largely an unrealized project. Another is to start a modern version of Black Mountain College — an educational model bringing different disciplines into dialogue.

That leads me to my final question, the one I ask in every interview. We often hear about architects’ unrealized projects — they publish theirs. But what about philosophers, sociologists, scientists, visual artists, poets, and designers? Outside of architecture, we seldom hear about their shelved ideas. And the scope of the unrealized is vast. So, as we wrap up this conversation, I’d love to hear about one or two of your favorite unrealized projects.

NS — That is a very personal and existential question in itself. Do you mean something truly unrealizable, or just unachieved yet?

HUO — That’s exactly it, which is why I’m curious about your take. It’s inherently existential.

NS — It’s an interesting question. And while not exactly what you’re asking, it does remind me of a reflection I recently had, about what it is that connects all my work, both the more sociological work that I have done on the topic of geo-social classes — partly with Bruno — and the more existential investigation I spoke about above. In the time of the Anthropocene, I believe we are divided, collectively and individually, sociologically and existentially, and it is these divisions that I am interested in investigating and describing. So, I would say, my yet “unrealized project” — one that will probably take a lifetime, or at least a career — would be to exactly map, comprehend, and develop a language for better understanding these fractures in the geo-social class landscape, and in our psycho-emotional or existential landscape. And why do I find that important? Well, because as every good tailor knows, if you want to fix or mend back together a piece of fabric, then it’s a good idea to first find out how it has splintered — and I believe the same counts for our social and our existential fabric, our collective and individual life-terrains.

Apart from that, I am currently writing a book about tech elites and their bizarre dreams of taking off to and inhabiting planet Mars, in which I try to describe why we shouldn’t pay so much attention to their silly plans, but instead just let them leave and say ciao, see you around, enjoy the ride…

HUO — Thanks for that. Just one more thought. In a world which is more fragmented, I feel like the idea of the “universal” becomes key. Not the old Eurocentric imperial perspective at all. Instead I’m drawn to my conversations with Souleymane Bachir Diagne who suggests universalism in the 21st century should be about celebrating the irreplicable plurality of culture and languages.

It’s not about replacing one perspective with another but blending them together, perhaps leading us to what Walter Mignolo calls the “pluriverse,” the many and the one mixing — to recognize all the different ways people see the world and having those perspectives speak to each other. I’m curious to hear your take on this decolonized notion of “universal”.

NS — I will have to think more about the question, but I think you are right in asking it. And what you say about a new sort of universality that starts from diverse modes of being, resonates with what Bruno called the “composition of a common world”. Another angle to consider is how climate change has become a universal concern in the Anthropocene. Regardless of geographical location or societal status, we are all in a situation where we must fight to safeguard the planet’s conditions of habitability.

And as I argue in Land Sickness, then this requires that we give up on the idea of “progressing straight forward” with absolute certainty, and that we instead go towards the future in a continuously reflexive and humble manner, mixing situated knowledges with curiosities, care, precaution and imagination — a sort of horizon, where we must remain open to the necessity of reinventing and renewing our ways of life, strategies and techniques, as we come to learn more about the Earth System and its workings. And of course, as you indicate, then this indeed also requires the pluralism and the plurality of perspectives that you mention.

As for unrealized projects, I will have to think more about it, especially since we’ll be discussing the topic in Venice in June. Ultimately, I think it’s about mapping out the pieces and fragments of this strange new universal situation and figuring out how to mend them. That’s also why I very much like your notion of piecing things together — it’s what we need to do.