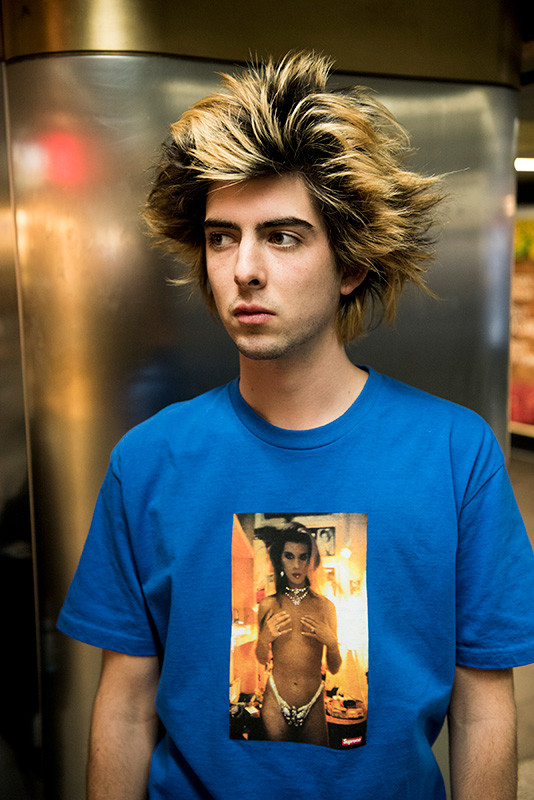

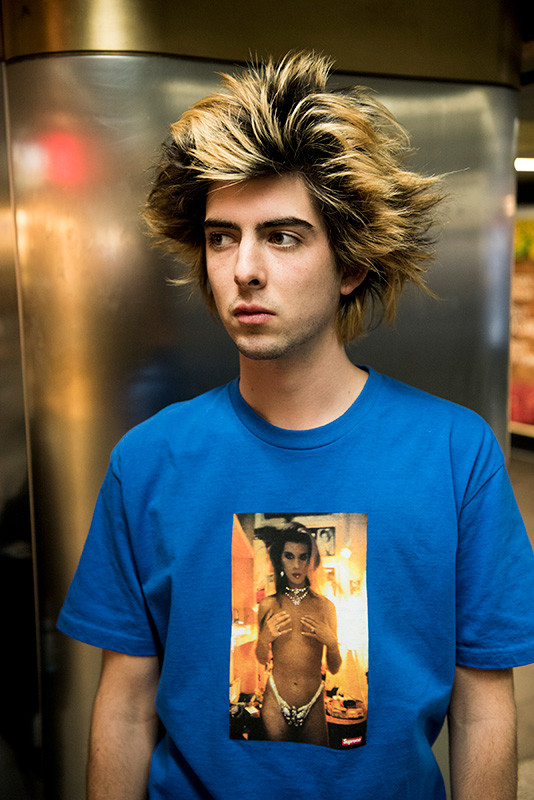

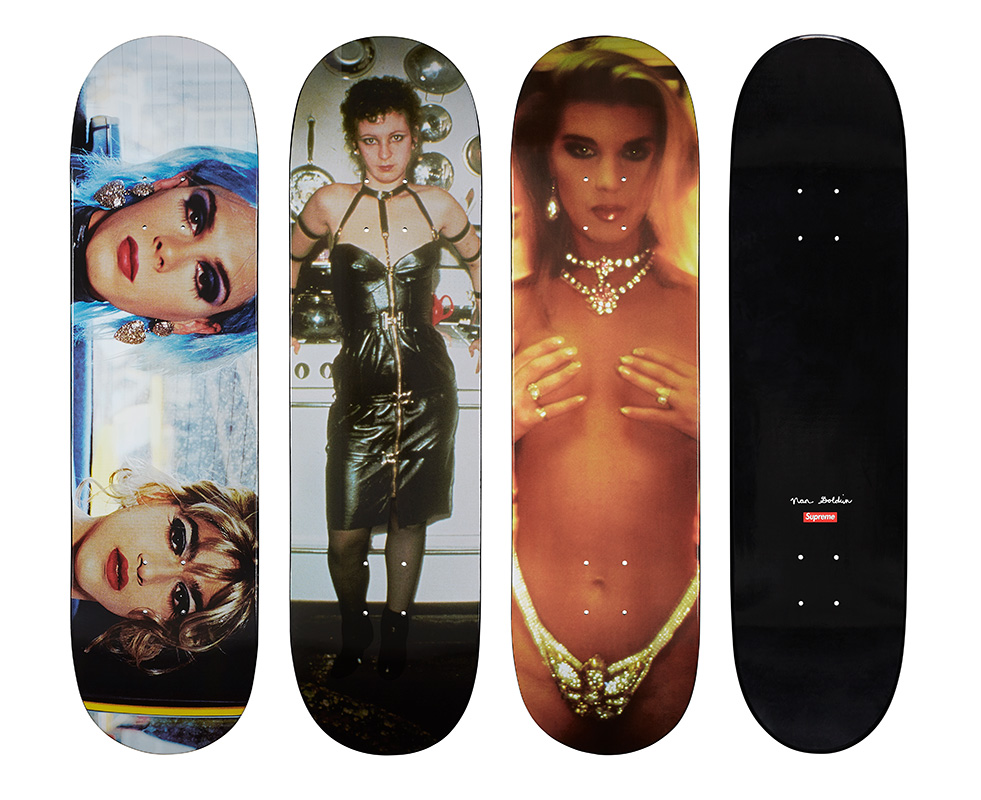

Nan Goldin Goes Supreme

Check it out now, and then go buy your camping supplies before it drops on Thursday March 29th.

Images courtesy of Supreme

Stay informed on our latest news!

Check it out now, and then go buy your camping supplies before it drops on Thursday March 29th.

Images courtesy of Supreme

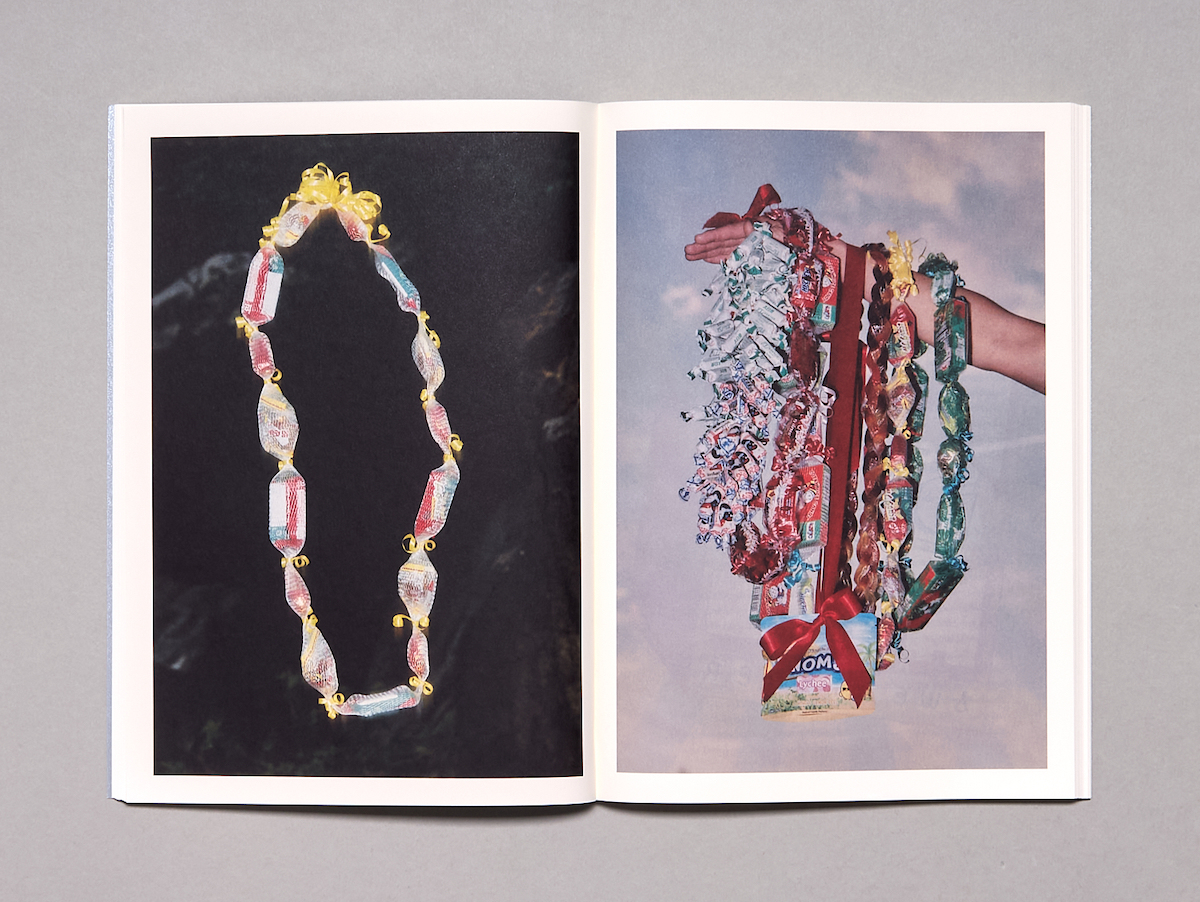

The launch party for this issue was no different from previous ones: a feast for the senses, especially taste, with botanical cotton candy spun onto flowers and Del Maguey-spiked mezcal jelly cakes. A few days earlier, I spoke with Tanya and Aliza about this new issue and the associations that it explores: candy as pleasure, childhood nostalgia, connection to distant cultures, as well as its roots in labor, gluttony, colonial extraction, and exploitation. With a diverse range of contributors unraveling these connections, Candy Land directs critical attention to familiar confections and flavors, highlighting their deeply person and historically global significance in their highly-processed and preserved glory.

Sofia D'Amico— Having just finished the Candy Land issue, I came away with the feeling that I’d read contributions from such a mix of people from different backgrounds— science, history, art, food industry, activism —and, of course, they’re each tackling the topic of candy from different angles. I am speaking from an arts background, but it’s a curatorial decision for these publications that you've put together such varied contributors. I’m curious how you pull together the community for each issue?

Aliza Abarbanel— The curatorial part of the process is the most core to what we do, and we are lucky to have a very robust community of people answering our pitch calls. At the end of every year we sit down and think about our themes for the year ahead. We had a really hard time deciding our summer issue and wanted to do ice cream, but we couldn't think about the right lens for the theme, because we don't just pick a food item, we want a specific context in which we're exploring and then refracting it in as many ways as possible. So with Candy Land, I played that board game all the time as a kid, and started thinking about how candy feels like it's so far removed from the land, but everything we eat is, at its core, tied to these organic ingredients. Candy has impacted the way we allocate and use land in different ways. So we set the pitch call in that framework, and get maybe 300 to 400 pitches per issue just for written content, not including illustration, and we also solicit from people. And as you've read, we probably have about 20 slots in an issue. Then a big part of what Tanya and I do with our editorial board is discussing how we can include as many different perspectives as possible.

Tanya Bush— Yeah, I think that's core to the Cake Zine ethos, that we are an interdisciplinary magazine. We are using these very narrow lenses to explore culture, art, history, and food. That's sort of what Candy Land allows us to access; it’s an interesting subversion of themes. So we have the piece “Candy Land: A Revisionist History” by Elaine Mao on the actual board game Candy Land, but then we have a piece by Simon Wu on kandi with a K, EDM, raver culture, and PLUR. And I think that because we have such a narrow theme, it allows for writers, artists, cooks, and people of all different backgrounds to hone in on something really specific. We have our first piece of fan fiction in the issue, which was really exciting and strange. For every new magazine that we do, we want to incorporate unexpected forms: taxonomies, fables, and listicles. We did a comic once. That was fun.

SD— Yeah, this made it such a rollercoaster to go through. With this issue, some of the features were really funny and joyful or more didactic or historical, and others had really dark undertones. It is a nod to the endless associations that people have with candy itself, in that in some ways it’s a marker of nostalgia, and in others, it's about gluttony or excess. Do you think about that balance when you're putting together an issue?

TB— We don't want to publish a magazine that's an onslaught of darkness, so we are very much thinking of an issue holistically… We want there to be a dynamic balance of hard-hitting reporting and more optimistic features with levity, as one needs in a magazine about dessert. We are first and foremost a magazine about dessert.

AA— With our issue Wicked Cake, the whole theme was talking about this dark side of a food like cake. I think famously of Matilda and Bruce Bogtrotter as a Wicked Cake thing that people would think about. But in general, cake is often super frivolous and fun. And for Candy Land, again, candy is so joyful. But more than any dessert we've covered so far, it's so linked to mass commodification, mass farming, and consumption. Most people don't make candy at home. We all know the history of the sugar trade in this country around the world, how it's linked to slavery and globalization and colonialism. A lot of these big corporations and their labor practices are impossible to ignore, so when tackling this theme, that was something that naturally came up. Part of doing a kaleidoscopic look at a theme would have to, of course, touch on that. But then we want the M&M fan fiction moment in there. We want someone who's diabetic talking about how sugar-free candy is campy and fun in the same moment, because those are obviously core to the candy experience in contemporary culture, too.

SD— And for both of you coming from the kind of food landscape, did you feel like there was a gap in a lot of publications and scenes that specifically connects food discourse with cultural production of different disciplines more widely?

AA— I think there are a lot of food publications that we really admire. I think MOLD and LinYee Yuan’s work is so incredible, and they do a lot of interdisciplinary and forward-thinking food work. Really, we did not intend to start what Cake Zine has become. We just wanted to make a magazine with our friends, then, very thankfully, we had a really great response to that issue and the party we did around it. That heartened us to keep going. Speaking for myself, leaving Conde Nast, I did want to make something that I could never justify to an international corporation business office as being a worthwhile pursuit.

TB— And we are a print only publication, which I think is worth reiterating. We are not constrained by covering hyper-timely stories. As Aliza is saying, we literally cannot because we print in the UK, so it takes a few months to get books over, and if we're going to try and publish something super topical, it's already going to out of vogue by the time that it comes out. So I think that is really liberating and exciting because it means that we're not sort of beholden to the traditional constraints that a larger media publication needs to be. Because we have this sort of niche audience, people really resonate with the more historical literary approach that we take.

SD— It's nice that you have this emphasis on your events too, because food culture is so much about community. And there's also this idea that the issue itself can act as or can deliver little pockets of pleasure. One of the topics that a lot of the contributors are nodding to is that there is this need for greater pleasure and nostalgia in a really challenging and difficult world. Do you guys have any personal reflections on that as you were thinking about the issue?

AA— I would say nostalgia is one of the biggest flavors. In all desserts, in every issue, we encounter people who want to talk about things from their childhood, family members, and recipes. It's interesting because it's such a personal feeling. I recently found out Tanya has never played the game Candyland, so I need to bring a board and we can play it, but it's not a good game as after reading the issue. It was created for children in the polio ward, so it's possible to lose. It means that as an adult especially, there are no stakes to it, but as someone who grew up playing it, I look at those characters and I remember being a kid and thinking they're so weird. They've been around for such a long time, and it's just kind of fun to consider the game in a new way. But, I would imagine for someone who's never played Candyland, reading that article was still interesting.

TB— Yeah, it's an iconic game that is such a part of the popular imagination, so even if I didn't play it, it loomed large. I used to have an extraordinarily fierce sweet tooth, but now that I'm a baker and I have to taste glazes and curds at six in the morning, the last thing I'm going to do is lunge for a Snickers bar. But, this issue has very much reinvigorated, maybe reawakened my appetite for the pleasures of candy at the right moment. I used to be someone who would store all my Halloween candy under my bed and savor it over the course of many months, and it was such a pleasure.

AA— Yeah, especially being a kid with candy, this concept of scarcity. When is your Halloween stash going to run out? Did your sibling eat the last brownie before you? And Paolo's piece is also about dumpster diving for chocolate and the dumpsters getting locked up in the Pacific Northwest and becomes more influenced by tech. This issue itself is almost taking a look at our moment of abundance, sweetness and how much candy is left in the jar.

SD— The issue also does a lot of that work too. In thinking about conglomerates, the implication of Chiquita is important. Also, even just on purely a level of underpaid labor. The piece that was on the Hershey's at the theme park and growing up in that neighborhood too, was this really interesting and kind of dark implication of this space, thinking about labor, especially in those contexts, the international student labor uprising was so crazy to read.

AA— Yeah. And we knew we wanted a story in our pitch guide. We called out Hershey, Pennsylvania and in general company towns because we just thought if we're doing a story about land, it would be interesting to hear from somebody who grew up in a place that was literally built for candy, but we didn't expect to receive this pitch from Maya that talked about her experiences working there and the experiences of other people working for Hershey, which I think that's why making magazines is so great is that we can have an idea for something and then it can end up being so much more.

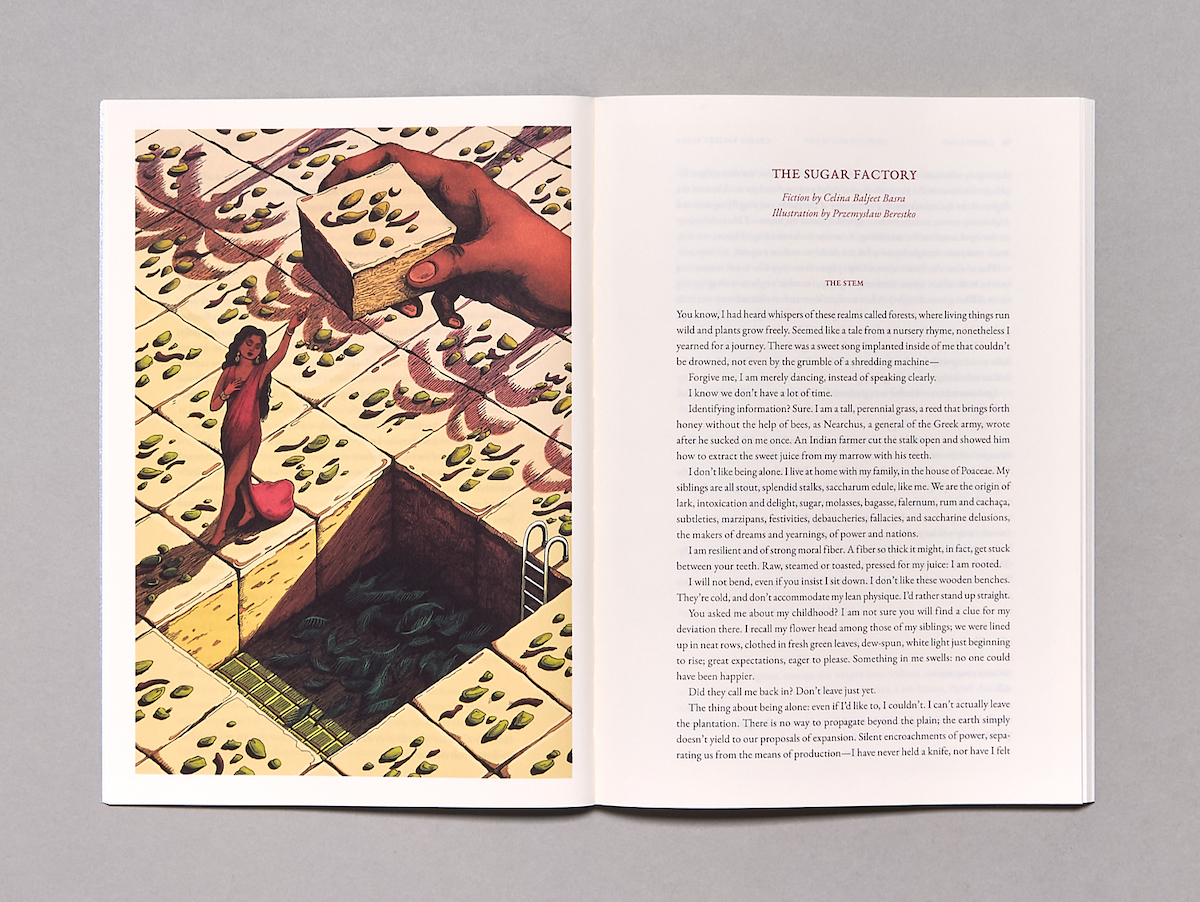

TB— I feel like now that we're talking about it, it makes me think of “My Father's Tongue” section in Celina’s piece, “The Sugar Factory,” which is sort of tracing the lifecycle of a stock of sugarcane to this mass produced sweet and the labor that's sort of involved in that. And I think it's cool that we have both this reported personal essay about a labor awakening and contending with the company town that you come from, and then also having that rendered in a sort of more whimsical literary mode where you're not necessarily being told exactly what's happening, but you can sort of intuit based on the factory calendars that the father is sending home and his early hours. You get the perspective from a variety of different junctures in the magazine.

SD— Yeah, the variety in the delivery and the different modes of writing are really effective. And then there are pieces that channel people's connections to an immigrant narrative or connection to a distant culture or family, too. So there's this interesting dual-narrative around labor as well as immigration, or thinking about diaspora and cross-cultural experiences.

AA— There's whole subreddits where people trade candy from around the world, or when you go on vacation and you bring candy back with you, it's one of those souvenirs that is so easily transportable and does offer really cool insight into what are the tastes of a certain place. That reminds me so much of some of the things that Gabrielle talks about in the banana candy piece about how she had a passion fruit skittle before she ever had passion fruit before. The way that things from other cultures and places can travel easier sometimes when it's in a candy form.

SD— In the research for this issue, this is kind of a silly question, but were you eating a lot of candy or in preparation?

AA— Certainly in preparation for this party, we have been spending a lot of time thinking about candy. There will be a lot.

TB— I’ve been incorporated into baking, but have just started testing something with Whoppers as part of the base crust. I love the taste of malt, so I feel like the issue has very much opened up the way that I think about candy in my daily life now and in my baking life.

SD— Oh, sure. Zoe Denenberg’s dirt n’ worms tiramisu recipe in the issue is so smart. I think it's such a cool reinvention of something that's so simple and quotidian, they were such a cheap treat, and this is such an interesting take on something and really making it contemporary.

TB— I love that recipe. Just to tease the party, Libby Willis is filling a literal six gallon fish tank with dirt and worms and we're going to probably have shovels on site and get people to sort of dig for their dessert.

Which brings me back to scooping chocolate pudding, oreo crumbs, and gummy worms onto my plastic plate. The genre-bending concepts at play in Cake Zine are well-demonstrated by the Candy Land issue, which posits candy as on the one hand a nutritional, ecological, and moral warning signal—like a neon dart frog. But on the other hand, candy is connection: to culture, to land, to one another and ourselves.

What is your ideal office?

Piera Wolf— Strong Wifi, tunes from The Lot Radio, books, plants, minimal interior.

Claudine Eriksson— Basking in natural light, remote, shared with friends working in other disciplines.

What is your most powerful tool?

PW— Trusting the universe: a journey of intuition and gut instincts and engineered serendipity.

If you were to assign a color to each other, which would you choose and why?

PW— Neon Yellow for Claudine, reflecting power, positivity. Swedish/Argentinian Sun, (emoji) flame.

CE— Silver for Piera, the SHINIEST and for reflecting lots of light.

Is there something you collect or have collected over a period of time?

PW— I'm not a collector — I enjoy journeying light — BUT I do have a rich library of different tactile paper samples.

CE— An unintentional but beautiful collection of patterned textiles from all over.

Which three words best describe your relationship?

Synchronized ping-pong.

What is your favorite movie of all time?

PW— One of them is I Am Love with Tilda Swinton that I first saw at the beloved Sunshine Cinema in the LES (before the theater got demolished).

CE— I could never commit to favorites, a definite answer would be too revealing.

Where was your last great meal in NYC?

PW— ‘Mission Chinese’ NYC — still hugs my heart.

CE— A bubby on the street from Asha’s Parlor, spicy and delicious.

Who was your first idol?

PW— E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial — I trained my voice so hard to sound like him saying "E.T. phone home".

CE— Mamma Trude!

What is the most interesting thing in your trash can?

PW— The many used chewing gums of my 2.5 year old daughter who recently became a fanatic chewer.

What are your favorite features of the human body?

PW— Hands (that create) and eyes (that go deep).

CE— Again, no favorites, but there is something special about shoulders.

Where did the name Jai Street come from?

The name Jai Street reflects the creativity that inspires our work, and that I initially found on the streets of the LES. Jai comes from my last name and is a modern pronunciation of the Sanskrit word for admiration or respect.

How do you select your features?

We look for is artists with a story to tell, appreciating artists equally regardless of where they're at in their career.

Growing up, were there any magazines you were an avid reader of?

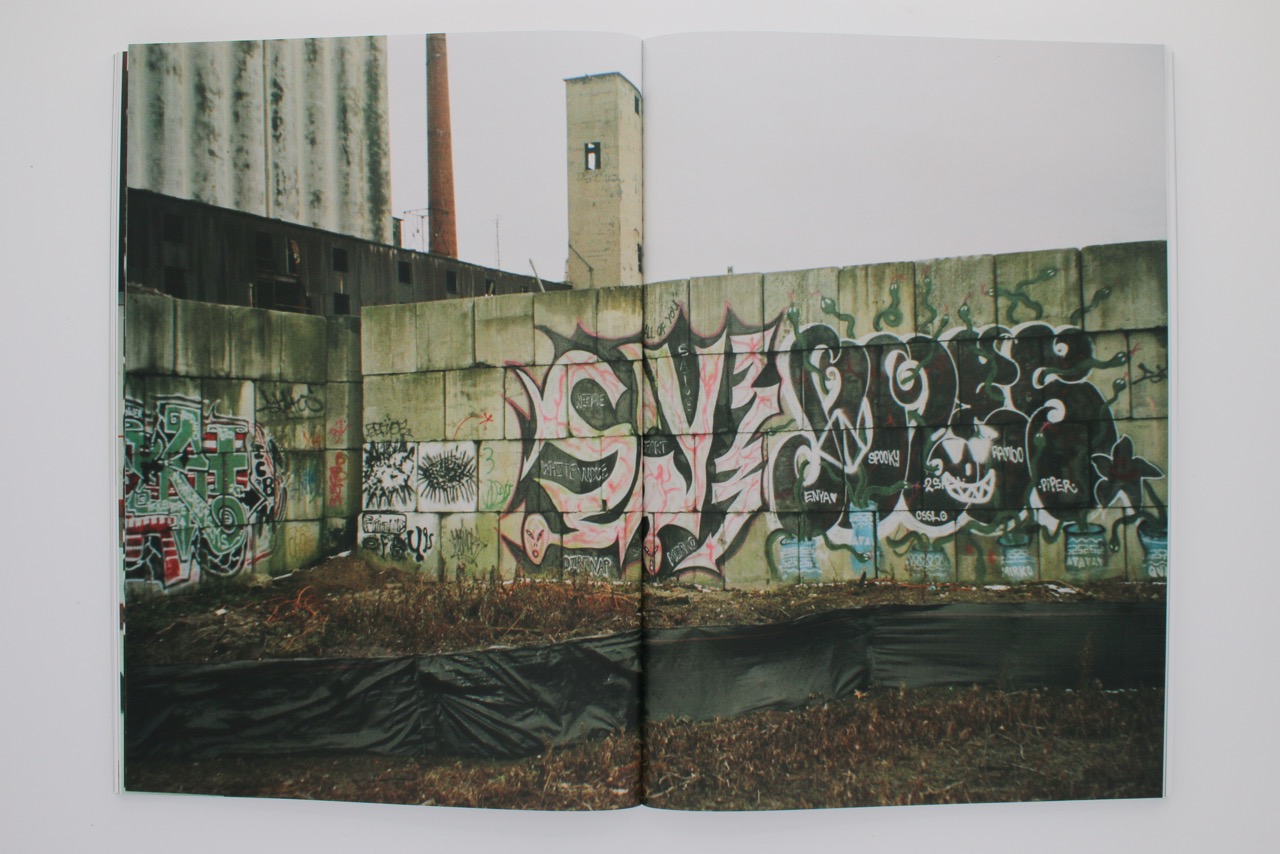

I grew up with and am an avid reader of 032c. This admiration grew when I was starting Jai Street. By trial and error, as I learned the ins and outs of creating a magazine, I had 032c as a physical almanac of all things culture. It was a sort of guiding star and inspiration, something to work towards. The fact that one issue could span from the streets of Berlin to Seoul to New York and feature such a wide range of people and stories was something I admired and want to do myself.

You say trial and error, was there anything in particular that you learned?

It's a bit of a hustling game when you're doing it independently. I spent last summer going around the city with copies in my bag, trying to get them everywhere. Distribution and getting it out there is really hard. You don't just make a magazine and get it into stores. We've been really grateful to sign with a distributor who's helping us create a map for this. There was a lot of pressure. What if people don't find it or come across it? But it also motivates you to create the best thing you can.

Have you learned anything about yourself?

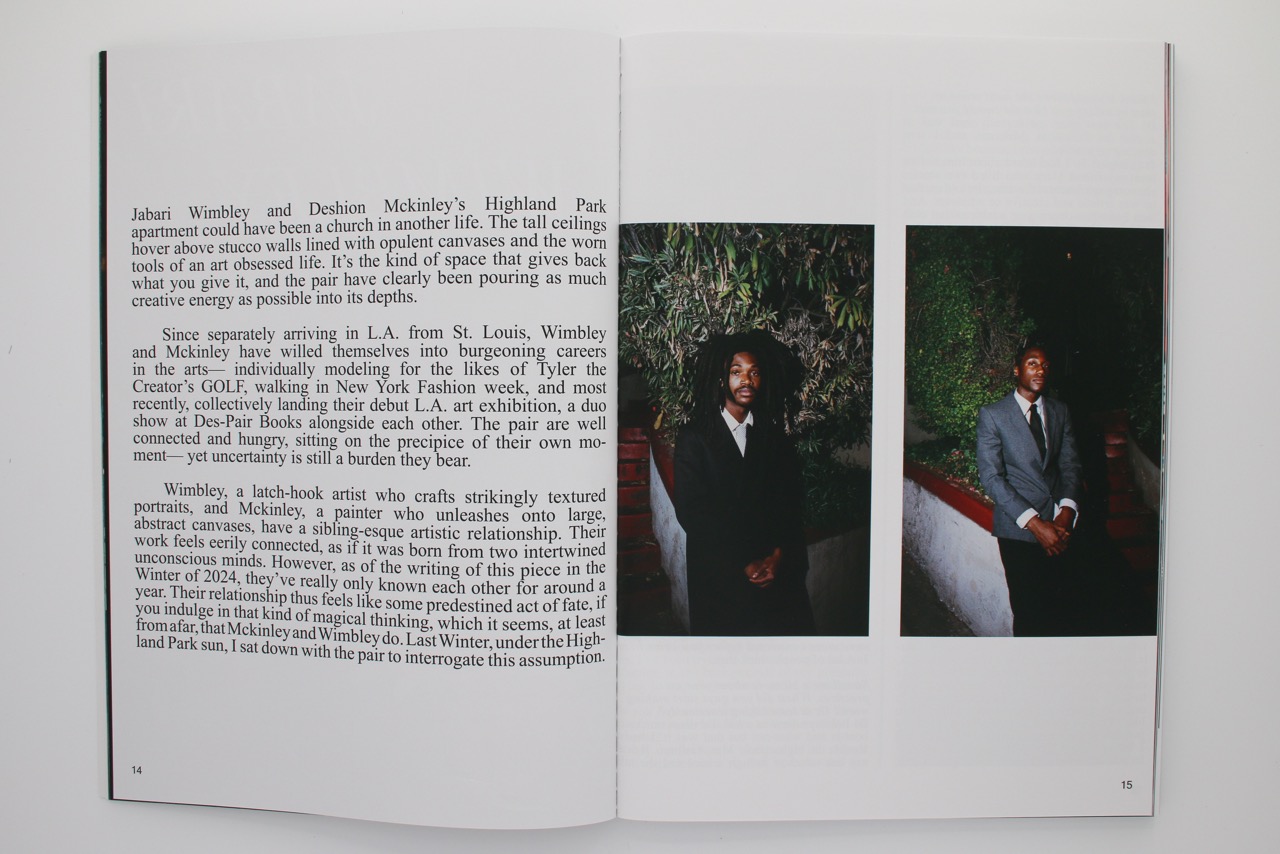

I'm naturally a really quiet person. While I prided myself in doing it all the first time around, I learned that's just not the way of doing it. That was me subconsciously protecting my art I think. Jai Street still reflects my POV but also all these other people I work with. I had no experience creating a magazine and was just learning along the way. I learned that, in a way, collaborating is what creativity is. Building a team has made our work much more sophisticated, nuanced, and honestly more interesting because everyone brings their unique perspective and interests to the table. Our team is not just New York-based. I’ve been working closely with Theo Meranze, a writer in LA who has connected me to many people out there and has been the reason for some of the new faces in the issue. Berlin-based writer and art curator Auguste Schwarcz in Berlin connected me to photographer Julien Tell. He is leading efforts to make our Berlin launch happen. There are many others.

What role has New York City played in all this?

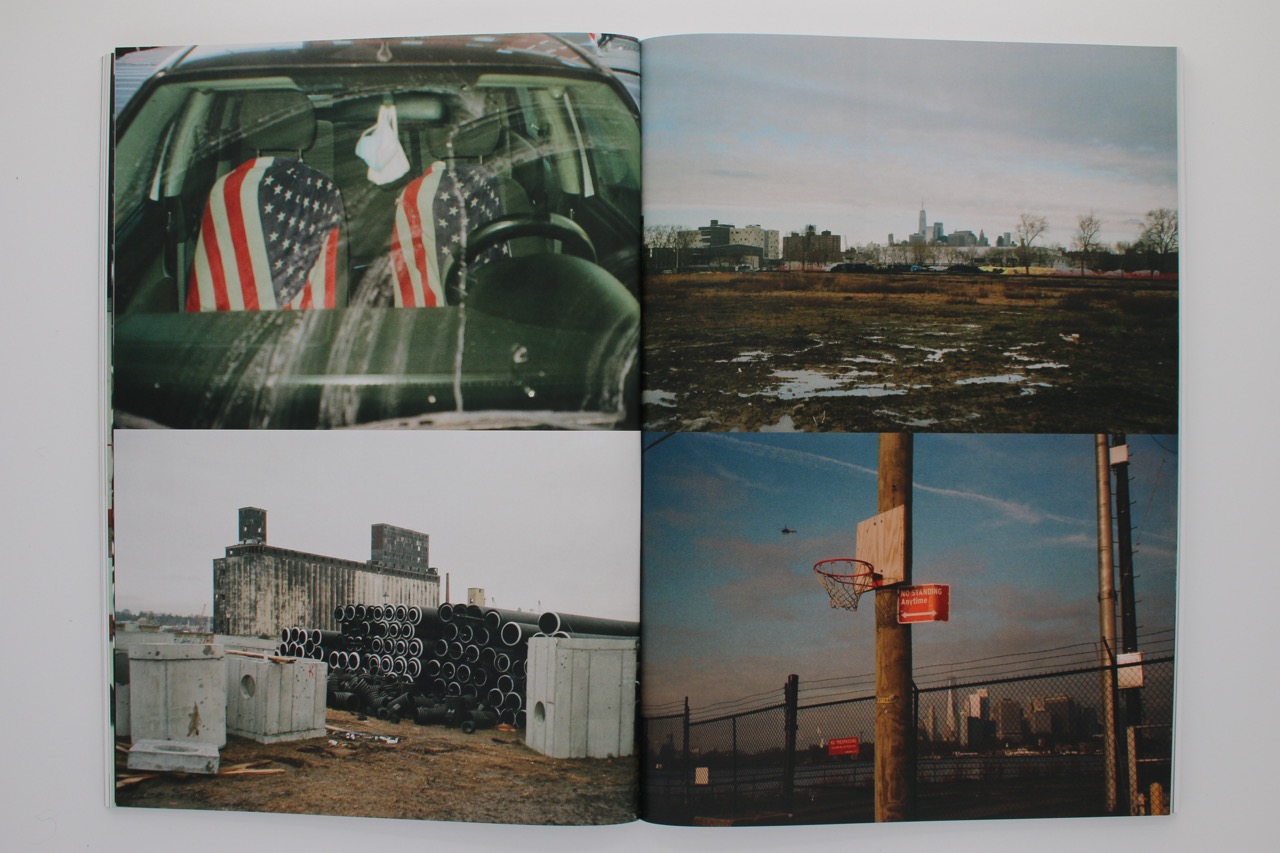

I started Jai Street out of a passion for the creative scene in New York. The first issue was solely New York-based contributors, which was great, but now I see New York as the foundation and I’m focused on expanding outwards. The second issue still has a lot of New York representation, and that's always one of my goals. There's a kind of grittiness to the scene here, where people are really trying to put themselves on and hustle for what they want. There's something beautiful about someone hustling for their first gallery show and finally getting it. That’s something pretty unique to New York in its essence.

Are there any stories in Issue 02 you’re particularly excited about people seeing?

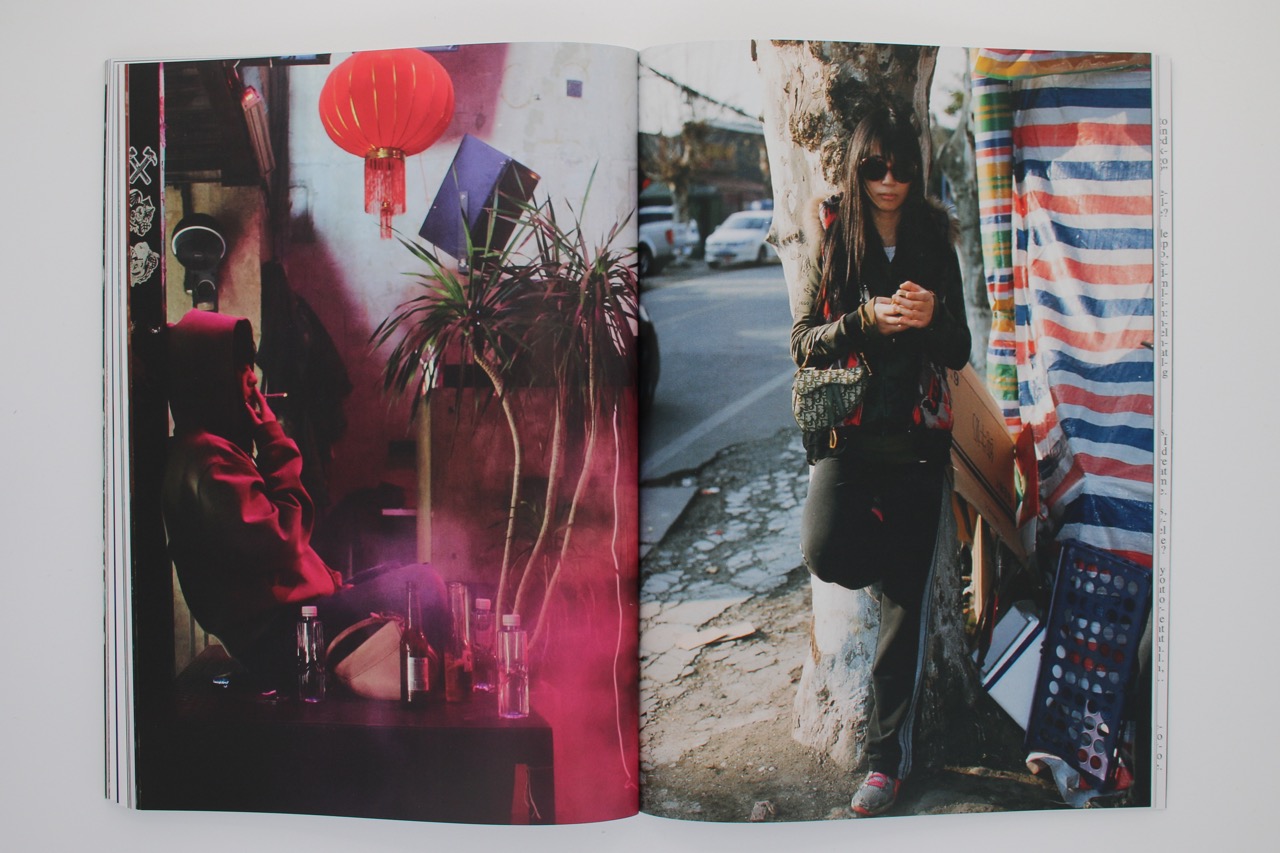

We are publishing a documentary-style photography introspective titled “Return to QiongLai” by Berlin-based fashion photographer Julien Tell in the issue. The series, very atypical to Julien’s traditional work in high fashion, follows a close friend on her trip back to her hometown in China during the Lunar New Year. The series paints a picture of the contrast between China's rural and urban environments, focusing on the life of native farmers in rural Sichuan and the alternative techno club scene of megacity Chengdu. The photos are amazing. The feature is also special because we are presenting and putting on Julien’s first-ever solo show at a gallery space in Berlin featuring these photos at the beginning of August.

We are also doing a story on an Oaxaca, Mexico-based art collective, Yope Projects. The group of six artists are up to big things, having recently shown and curated shows in Los Angeles, New York, and Mexico City, but also shine a light on the greater art community and emerging scene in that particular region of Mexico, known as being the country’s center of traditional craft and commerce.

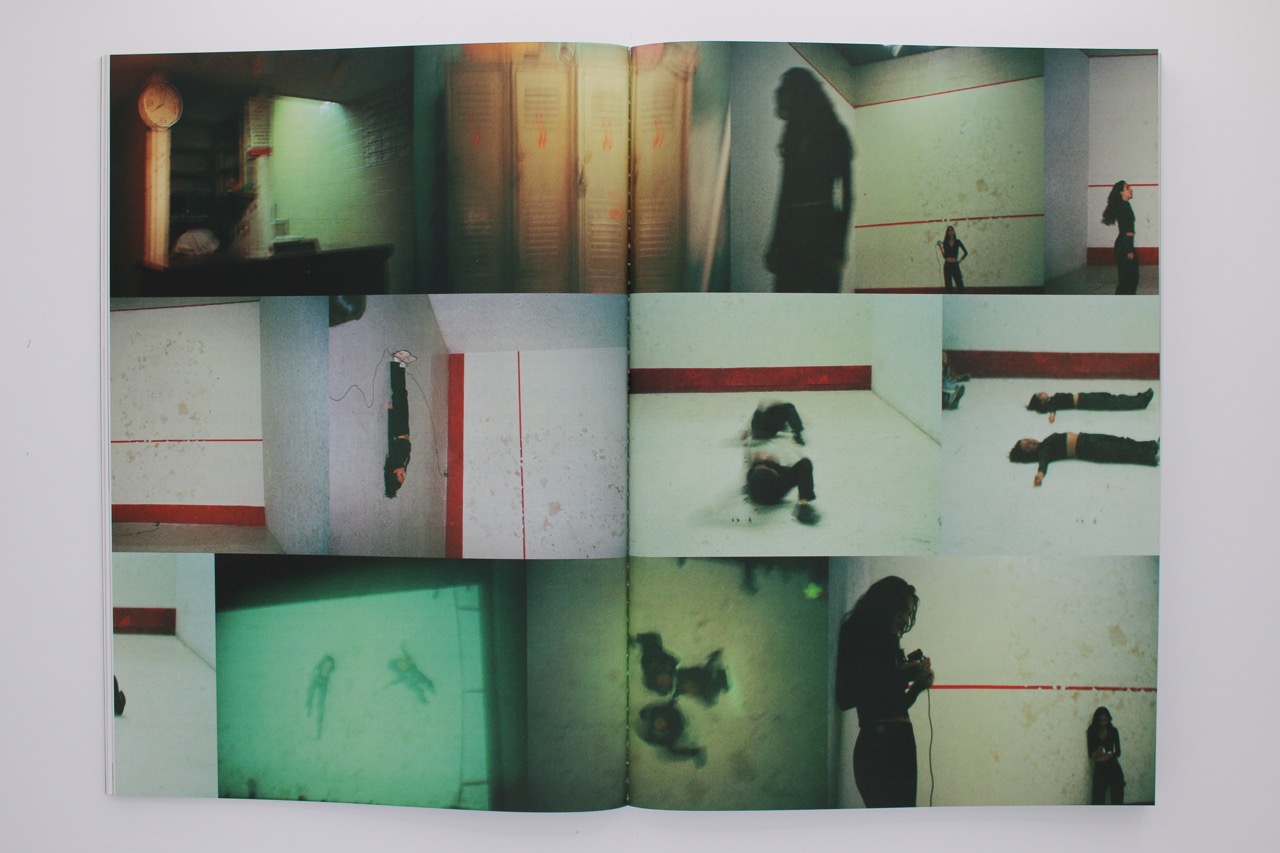

I’m really proud of our story with Isaiah Barr. A New York native, Isaiah's also a musician and founded the art and jazz ensemble Onyx Collective. Isaiah’s yet to have his photography in print and has had an idea to lay out a series of photos he took in succession to replicate a film roll. We made that vision come to life. I thought it would be interesting for Isaiah to pick an interviewer and for them to come up with questions based on their relationship with him. He chose his partner, Renata Pereira Lima.

Isaiah Barr, "Dimension Zero"

Do you agree with the notion that print is dead?

I feel like it's the opposite, although it was a bit ironic that you just announced pausing your print magazine. For me, those who appreciate print and everything that comes with it — physically turning pages of a magazine and seeing print as a vehicle for physical design — are still all in. With that being said, the business model of publishing as a print publication is not the greatest. Production costs for high-quality print are high, and distributors and stockists are conservative in who they buy into. They opt for consignment before wholesale given their margins are so small. It’s understandable but something we are trying to work around.

Publishing Issue 02, I’ve learned there’s a balance we have to strike between coming to terms with what, say, a store in Germany can do that may not be as beneficial to us cost-wise, but the flip side is we gain exposure there to a passionate market we wouldn’t otherwise have. We’ve also been fortunate to sign with an international distributor in the UK. The team there has been great in setting a roadmap for getting Issue 02 and the Jai Street name to Europe and Asia, where I think print may be a bit more appreciated and accessible.

As I'm building Jai Street, I'm also defining what the brand stands for and the kinds of stories we tell. The print magazine is our platform right now to do that. We make exceptions in terms of trying to make money off the print magazine to gain exposure. Let's get Jai Street everywhere to build this brand to the point where, in a couple of years, we can create more tangible physical experiences like galleries and group shows. So for me, the magazine is not an endpoint but a jumping-off point.

Looking forward to your next issue, what do you plan on maintaining?

Jai Street is built on an eye for curation. We believe creativity is about how stories are told. I consider myself a storyteller and want to ensure we're focusing on highlighting creatives globally, like the latest issue which features essays, interviews, photography, design, and art representing voices spanning from the clubs of Chengdu, China to design studios in Los Angeles, to back alleys in Tokyo, and back home to New York. Also making sure to feature people that are still on the rise like us. For many, this is their first time having work in print or undergoing a full-length interview and profile of their work. For any artist, that’s exciting and motivating. I think that’s why those features feel very connected to Jai Street and become all-in to what we’re doing.

Shop Jai Street here.