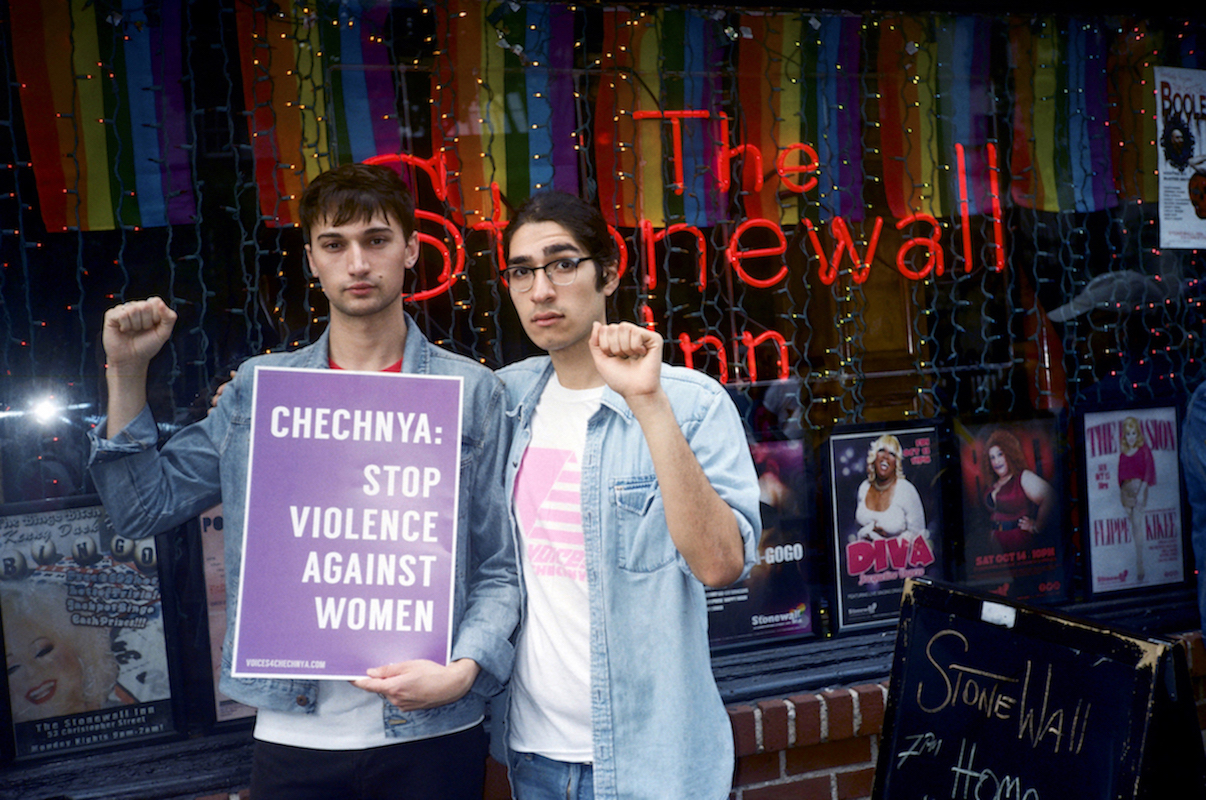

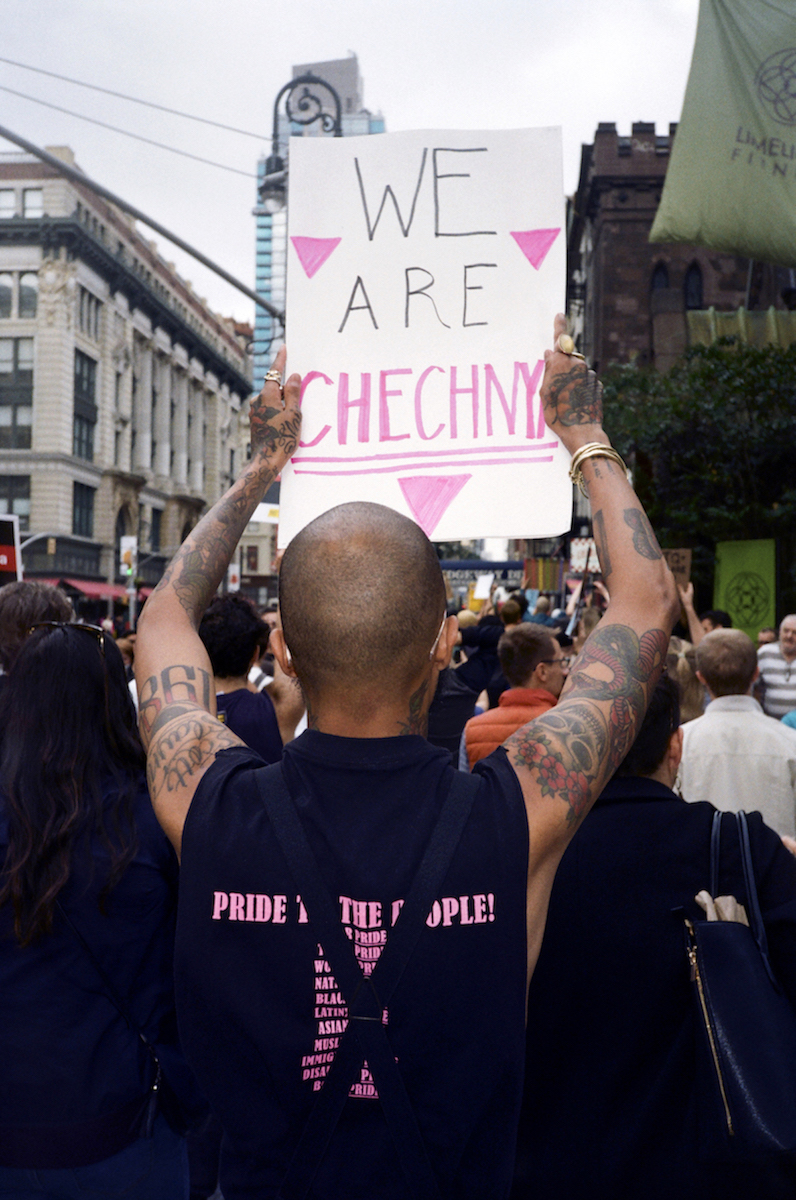

Voices 4 Chechnya

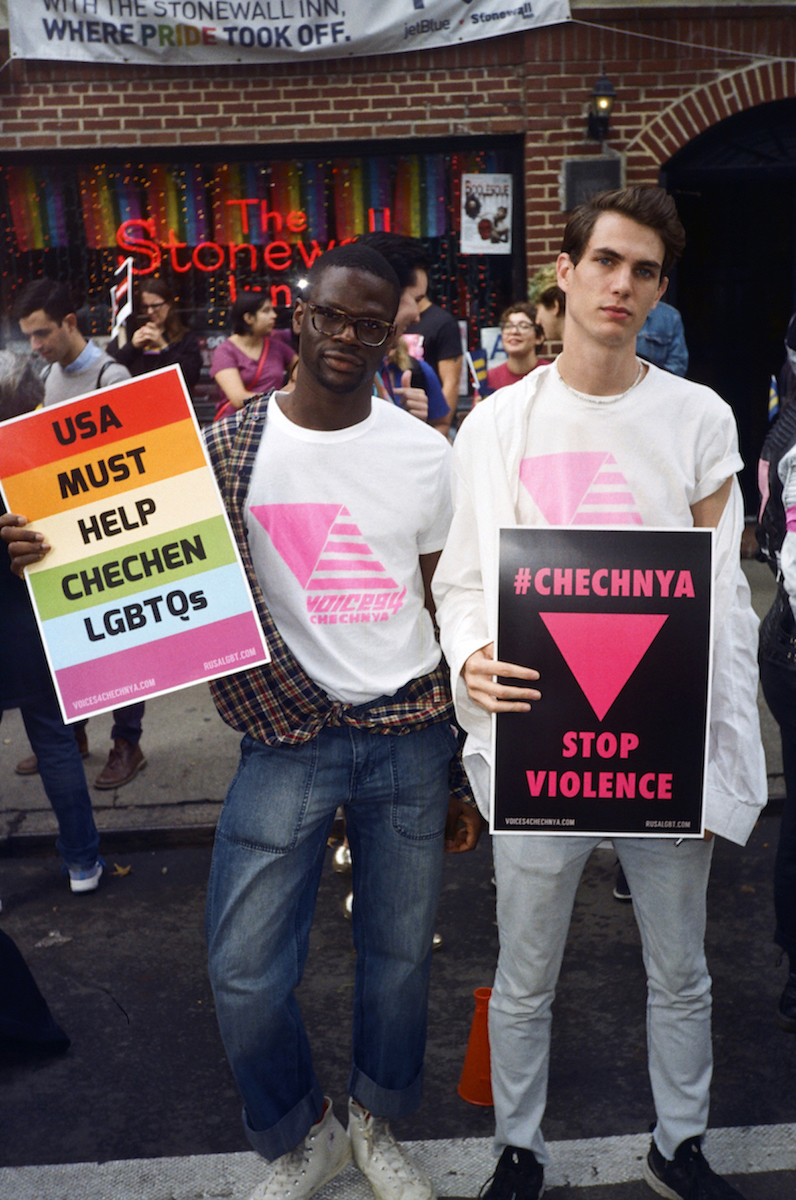

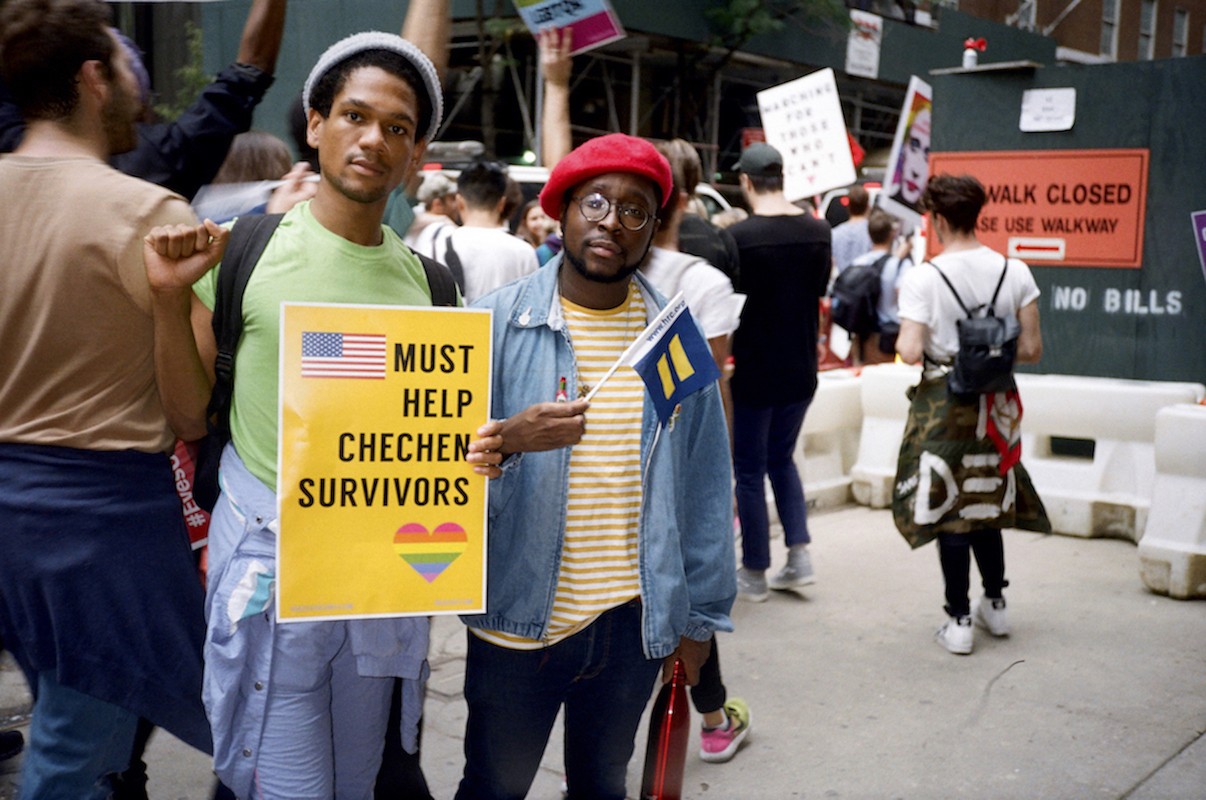

Speakers at the rally included Voices 4 founder Adam Eli, Russian-American journalist Masha Gessen, Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum, and Voices 4 founding member Marc Sebastian Faiella. RUSA LGBT member Nina Zaretsky was joined by Voices founding members Ricky Santana and Lae DuBoi who each read personal letters obtained by RUSA LGBT from Chechen asylum seekers and survivors.

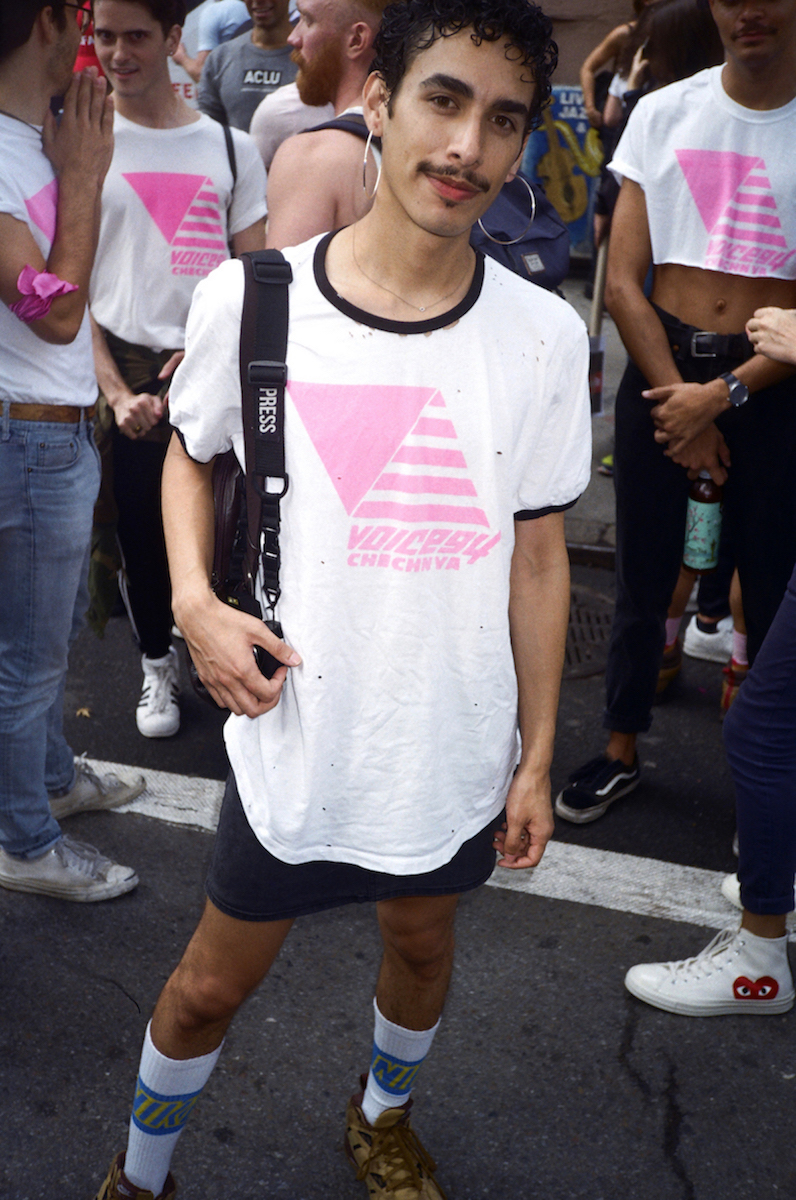

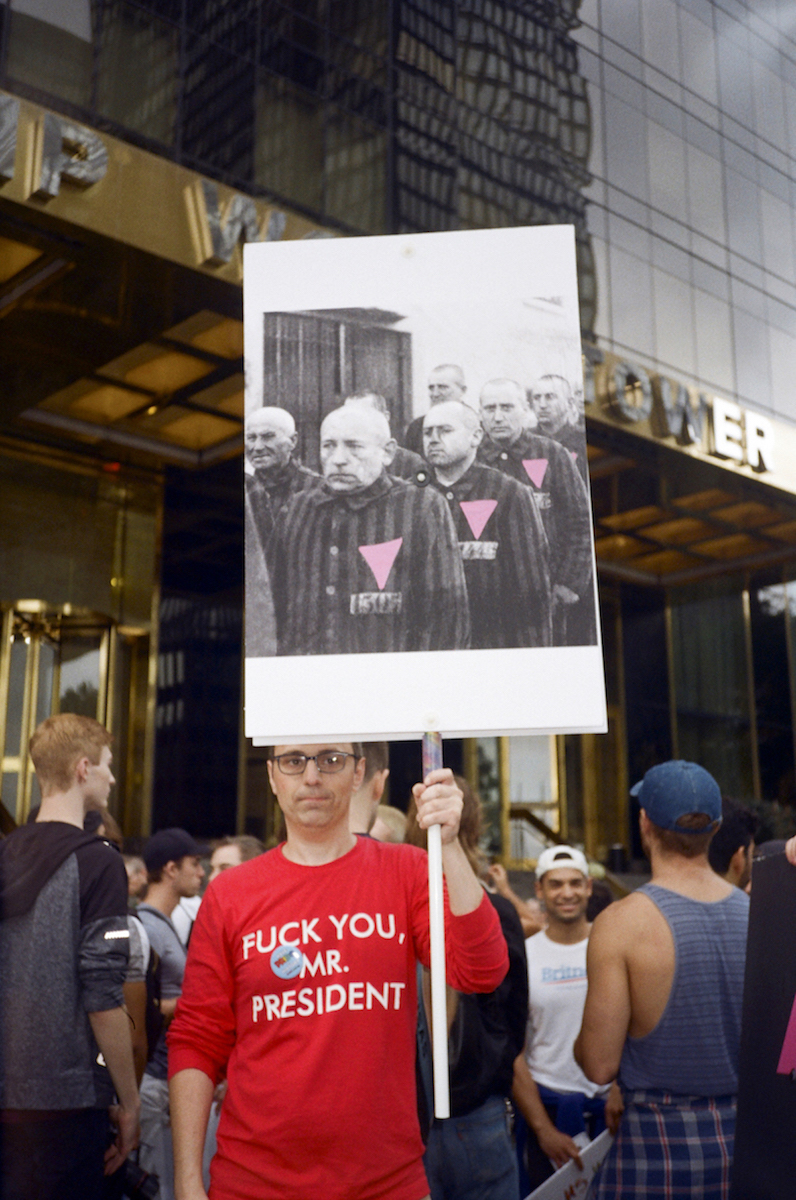

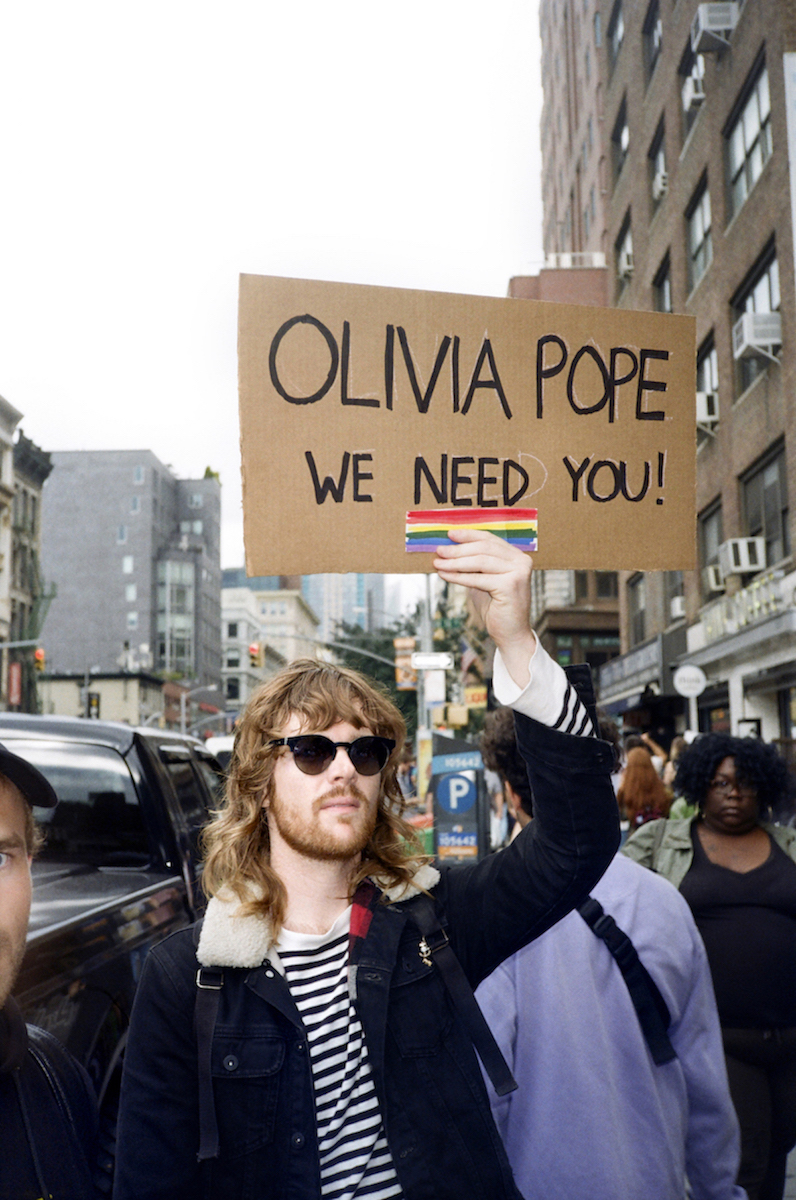

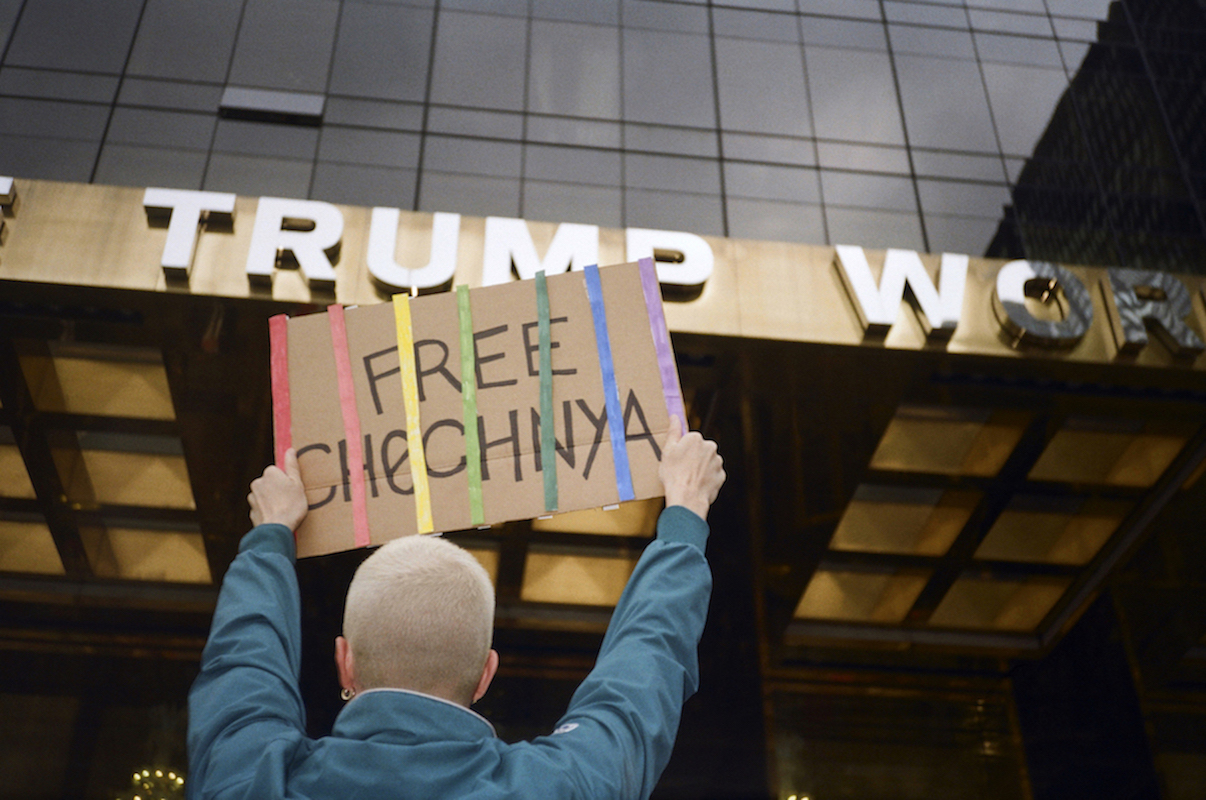

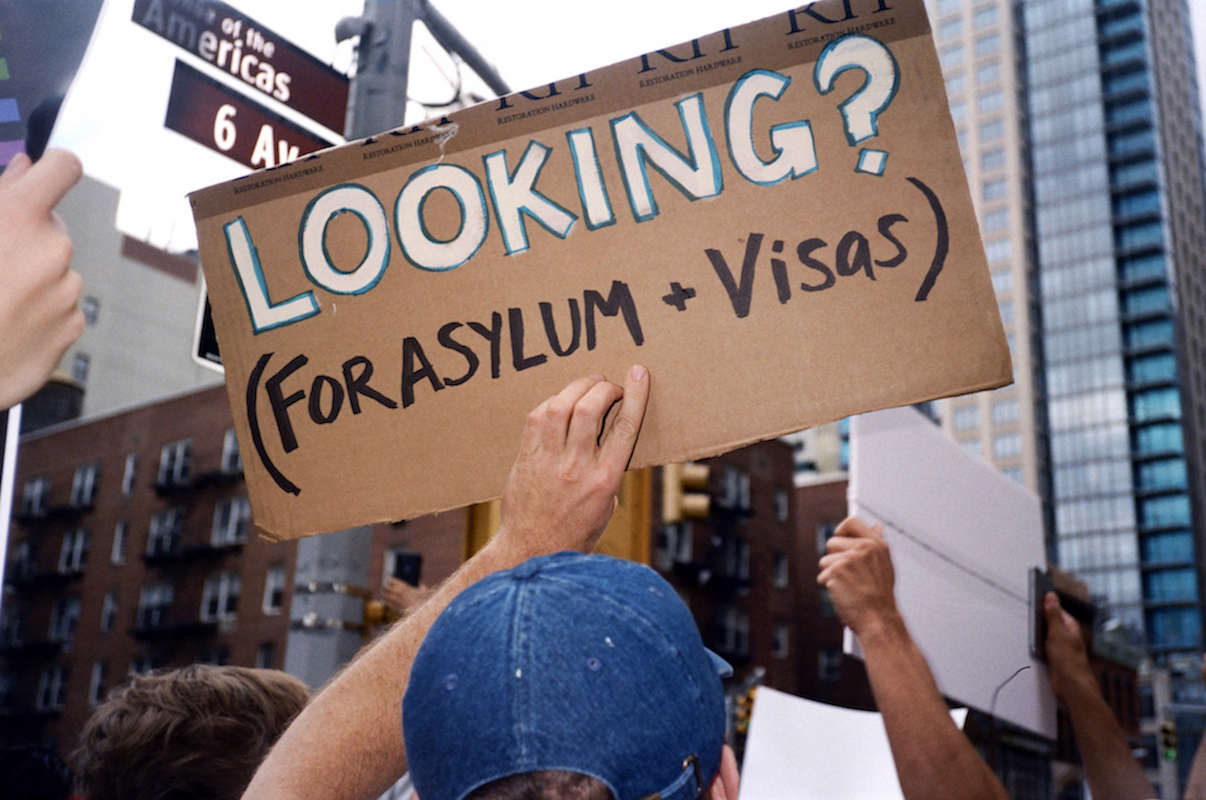

Following the rally a march took place from Stonewall Inn to the steps of Trump World Tower at the United Nations Plaza on the Upper East Side. During the march, designated marshals from Voices shielded the participants from oncoming traffic with additional support from city officials. Many onlookers displayed support for the cause with gestures of solidarity.

Once at the tower the group re-stated their demands for humanitarian parole visas from the U.S. Government for Chechen LGBTQ+ people. A group photo was taken before the participants peacefully dispersed. Participating in the march made a difference in my life in that it allowed for direct action against our government's current silence on the Chechnya situation and expression that we are all one human family.

In the LGBTQ+ community, if you mess with one of us you mess with all of us; we will continue to speak up and act up until all have the rights, safety, and respect that they deserve.