Dolce Far Niente

The result was an exhibition that juxtaposed sweet moments against the current era of socio-political unrest and racial tension, in which McGarrell envisions a future era that is decolonized and no longer centered on bodies of color and queer bodies being worth capital or labor. Though her proposed utopia is not free from oppression, lo-fi textures and moody hued photos offer viewers visual proof of a lived experienced that oscillates harmoniously between pain, love, and joy.

office sat down with McGarrell to talk about what she hopes viewers will take away from this new body of work and how their contribution to Art Hoe Collective has impacted their own creative practice.

When did you first start practicing photography? What do you like most about the medium?

When I was 10, my dad took us to Guyana in South America, where he was originally born. Before this trip he got a point-and-shoot camera as a rebate from Staples and gave it to me because I’d always been obsessed with toy cameras. For a while, I just fooled around but as I grew older I got more into it. Then in the 8th grade, one of my childhood best friend and her entire family passed away in a plane crash and I developed death anxiety and started documenting everything and photographing everyone I loved. What I like most about the medium is it’s potential to make moments into something seemingly eternal. Photography, especially film photography, promotes the illusion of longevity, and if I could make moments of warmth, happiness, and beauty last even a little bit longer, I would do anything to achieve that.

Do you prefer film or digital photography? Why?

I prefer film, but it’s fairly inaccessible to people of color. I think the privilege of being able to shoot film combined with its physical nature gives it a mysterious quality. Film allows us the ability to manipulate photos as if they were taken in any era, whether it’s from 1925 or 2015. Film photography creates these permanent objects and captures a moment’s tangibility. Like I said, I became obsessed with saving pieces of people. Film gives me a slice of someone’s reality that I can keep forever.

What inspired this body of work? What emotions and themes did you aim to capture?

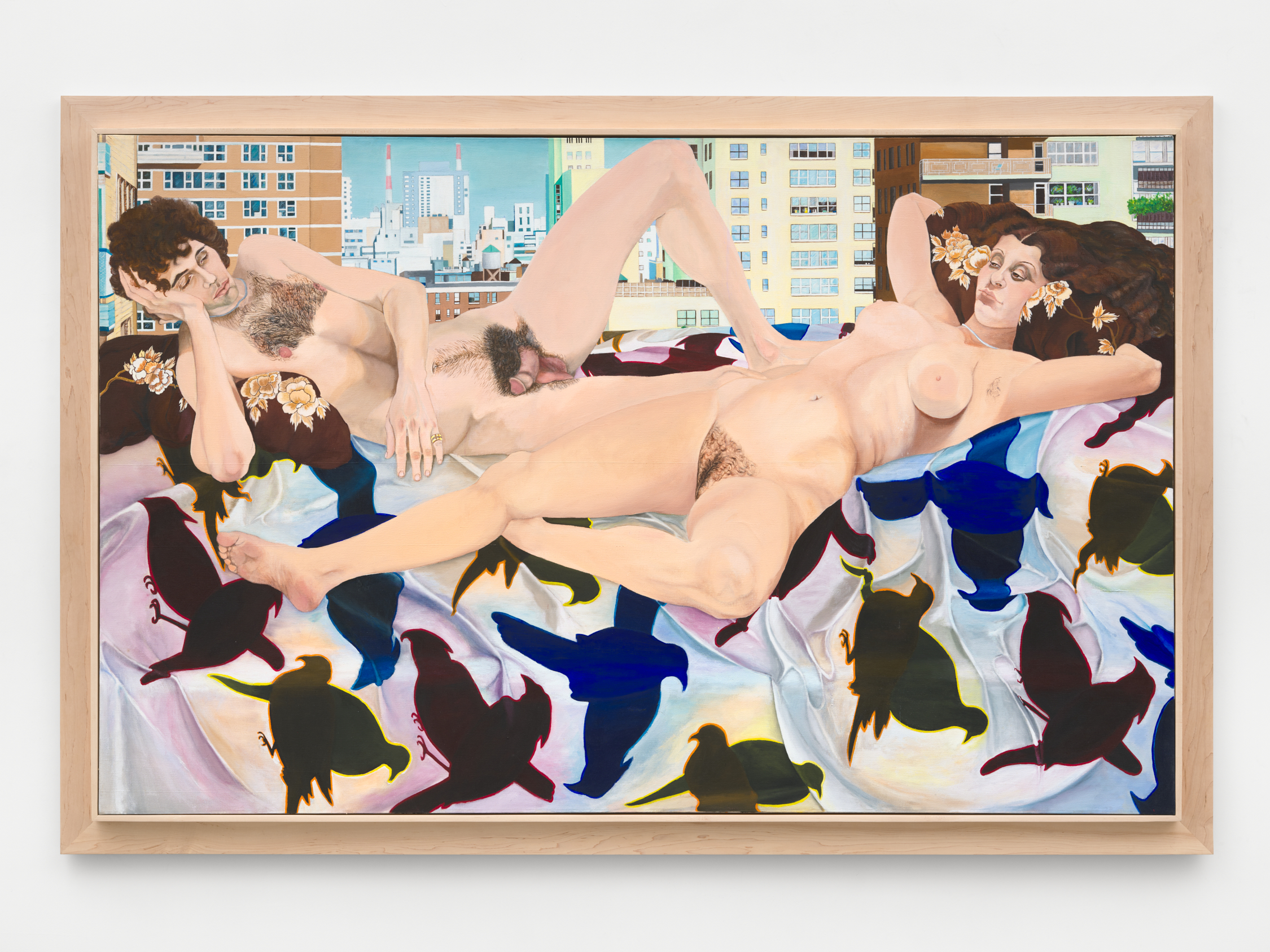

This body of work was inspired by moments of sweetness and how we battle with oppression and our own mental health to enjoy them. I was inspired by cycles of love and death and white supremacy and how I fit into their grips. Some themes I wanted to cover were memories, the cycle of life and death, oppression, the feeling of peace, and reclamation of our bodies of color.

What’s the title of show and what does it mean for you?

The title of the show is “Dolce Far Niente”, an Italian phrase, meaning “the sweetness of doing nothing." I heard this phrase on a flight back in April. I was running away from New York at the time and in a headspace where I wanted to leave every negative thought behind me, but it had come from a place of whiteness and privilege, where I was trying to out-run my oppression. I sat and thought about romance languages and love and all the beautiful words that exist to define life and how people of color are never included in these sentiments. To me, it means reclaiming this notion of peace, that as POC, we have not been afforded.

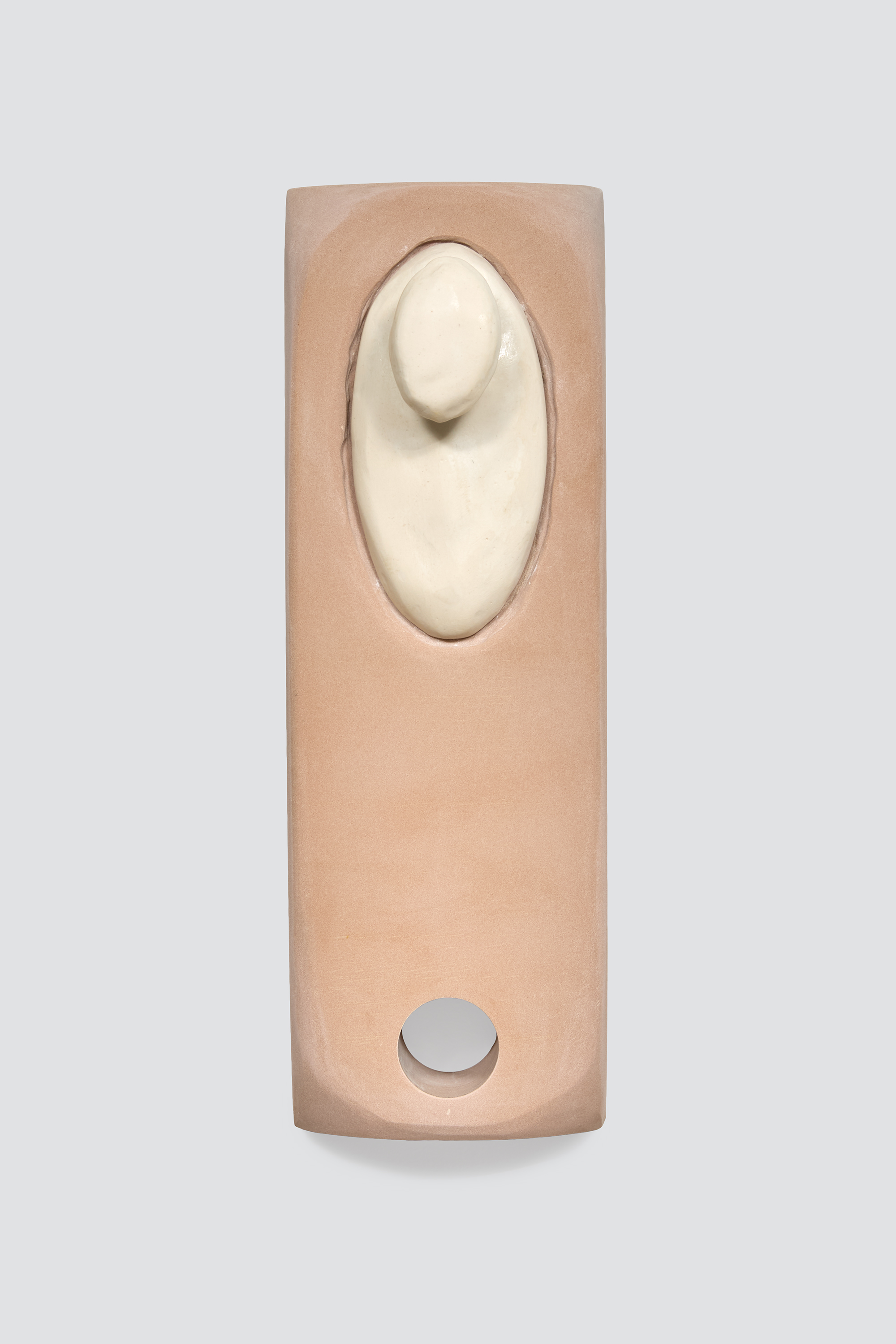

Why did you choose to showcase symbolic objects alongside the photographs?

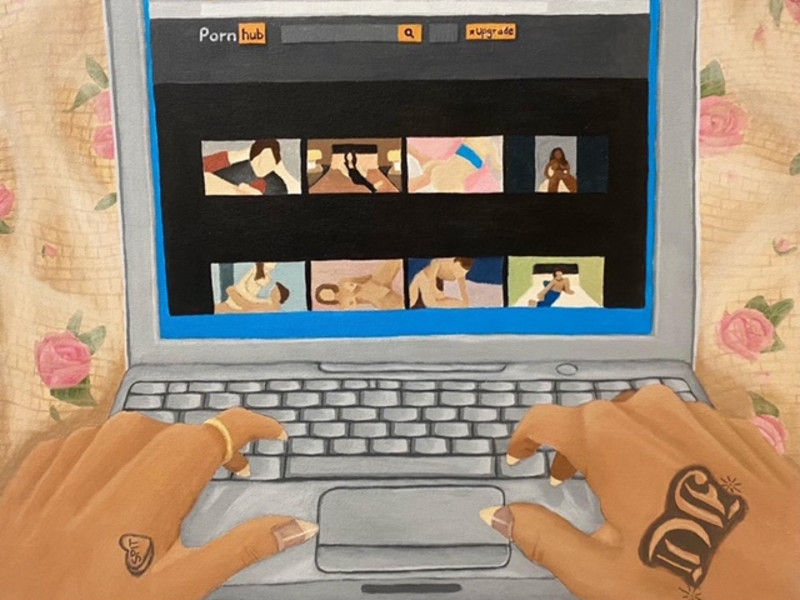

We decided to set the show up so that the viewers could be lured from my surface world into my mind. The symbols are archetypal symbols of blackness, mexicaness, and symbols of tradition. Many of us from different types of blackness share collective experiences yet, due to anti-blackness, separate ourselves from the typical notion of blackness. As someone who is a black latinx person, I wanted to comment on this melding of identities and acceptance of blackness as an identity with varying experiences. The objects also represent pieces of my childhood that oppressed me due to their relationship with colonialism. Topics such as religion, beauty, entertainment, and so on have all used the black and brown bodies to force their ideals on. The roses among other symbols represented this idea of life and death, in which we observe and appreciate beauty, but ultimately let it fade. Much of the lives of black and brown people are full of having to bury our families and friends due to oppression-lack of accessibility to healthcare, transphobia, gang violence, and poverty so I wanted to use general cultural markers that comment on capitalism and how it oppresses bodies of color.

How has working as a curator for Art Hoe Collective impacted your own creative practice?

My work as a curator has impacted my work by helping me realize the importance of creating work that is accessible. A lot of artists have the self-conception that being lofty and out of touch with this realm will give them a sense of importance or “specialness”, but as someone who finds themselves so intertwined with their community, I want to make something universal in a sense.

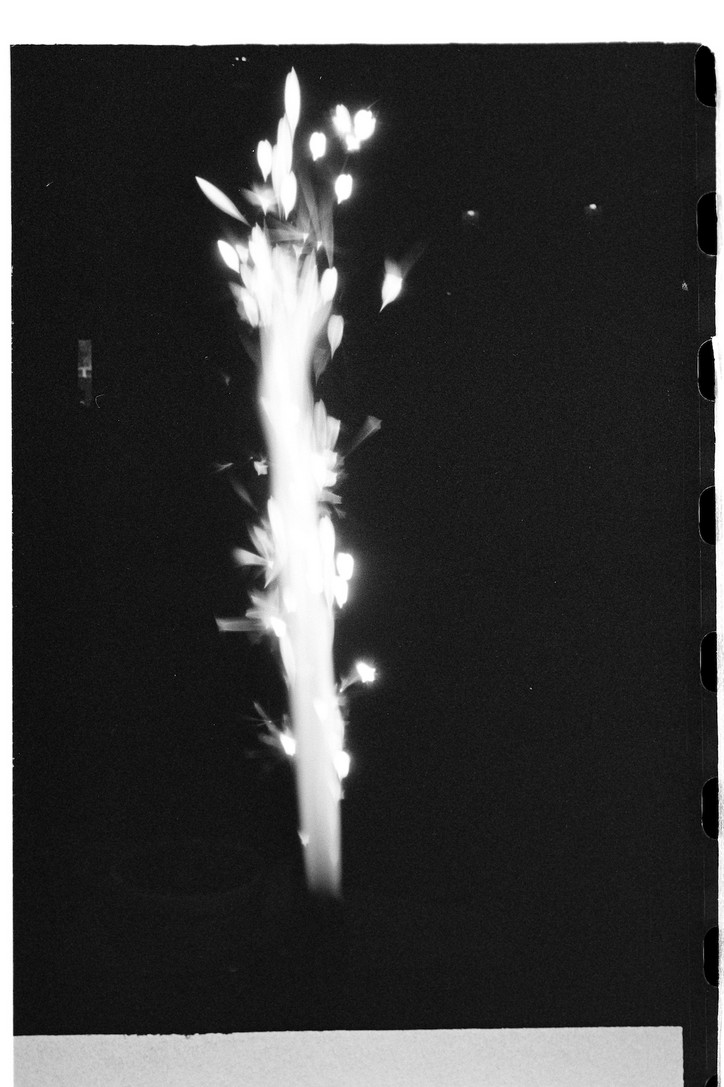

What’s your favorite image in the show, and why?

My favorite is definitely "let you in last night" (the one through the window). It’s a self portrait with a cable release going through the window. I think it’s my favorite because of the process and all the different thoughts and emotions that went into making one photograph.

I was deathly sick for about 2-3 weeks in June. My partner came to visit and I was having crying fits because I was too sick to go out and have fun and I felt so bad. Before they left to return to California, I had a barbecue and bunch of my friends came over and I had the worst fit of anxiety because I hadn’t seen anyone in so long and I was feeling overwhelmed and worried about being judged by my friends for whatever reason my anxiety episode produced. I was surrounded by queer people and I was still worried how my relationship would be perceived. At the barbecue, I looked through the window and saw my partner, in my room taking a deep breath, because they have anxiety, too, and I came to the conclusion that queerness and love and anxiety have always gone hand-in-hand for me, for so many of us.

I felt so voyeuristic having this moment of realisation looking into this window and started to think about all the voyeurs on black and brown queer and trans bodies, all the inquisitive looks and thoughts, that sought to not understand, but categories that adhere us to some sort of binary that’s understandable to them. I sat with these thoughts and eventually called up my friend Munachi, who is also gay, and shares with me, his struggle growing up in Delaware, a place where people like us are forced to move through the shadows with our love, and we shot 3 and this was the one. I saw it when I got the film back and I fell in love. The fact that I asked a different friend, a cishet man, to help me hold the camera while I fired it off and he tried to claim that it would be his photo if he acted as a human tripod. He tried to claim ownership over my ideas and over my queer body, and I had to find a way to do it myself, which was the cherry on top of it all. It seemed so fitting that in this idea talking about external forces judging, abusing, and profiting from people’s queerness that a straight man would say his assistance would make it his photo after I had focused the camera, set up the lighting and all the items that show in the shot, and had the self cable release to press the shutter, he’d still say that.

As I’ve gotten to know you better in the last few months it seems like two major through lines in your work are the power of vulnerability and community. Would you say that’s an accurate statement? What do those two concepts mean to you?

I’d say that’s definitely an accurate statement. I’m constantly analysing the ability to be honest and vulnerable in cultures that are extremely traditional, conservative and homophobic. Since I was a kid, I’ve been testing boundaries with my family about what is acceptable with my behaviour and appearance. These concepts together, discuss my desire to reclaim and transform my culture into something that can be sustained and passed to the next generation in the community. I am vulnerable to let people in, so they can see how I see myself, family, and surroundings. I let people in, because when you love and trust people, they become your community. Community has always been a big deal for me, living between the suburbs, where I was ostracised for my being, with my Mexican side of the family, where I was accepted but othered for my blackness, and with my black side of the family, where I was punished and not understood for being loud and expressive.

What do you hope viewers will take away from seeing these photographs?

I hope viewers will gain a reclamation of their bodies and their spaces of peace. I think in tumultuous times, we forget it’s okay to say, this is about me, or forget we’re allowed to react however we do to oppression and we have to take our space to rebuild our security. I hope they take away the fact that our cultures and what others deem weakness or use to oppress us, is our strength and what keeps the world colourful and beautiful. To be able to reclaim our bodies and cultures and use them as a tool to decolonize and be vulnerable, is to me the greatest desire of all because it’s freedom. To be personally free from the white standards of acceptability, yet still accept ourselves more than ever.

What's next for you?

The universe knows what to send us and when, where we're needed and for what. My plan is to just go along with the ride.