London is Burning

How splendid and exotic are these enduring creatures of the night, don’t you think? To meet their compelling gaze is to feel the story of a worldwide wonder: the slippery crux of what it means to be male, female and alive.

office spoke with curator Vincent Honoré about this fabulous exhibition.

It feels important that the works are self-portraits—how did this choice inform the show? Are these essentially elevated selfies?

As drag is about freedom of choice, firstly how an alter-ego is created and what kind of meaning is attached to an alter-ego, it was important for the artists’ work to speak their own language. It was also crucial for the exhibition to belong to the community of drag, and to avoid any voyeuristic approach. In the self-portraits, artists are both object and subject: one of the possible definitions of drag.

The span of the show goes back to the '60s. How do you feel drag has changed since then? Are there examples from before then that, if you could, you'd like to include?

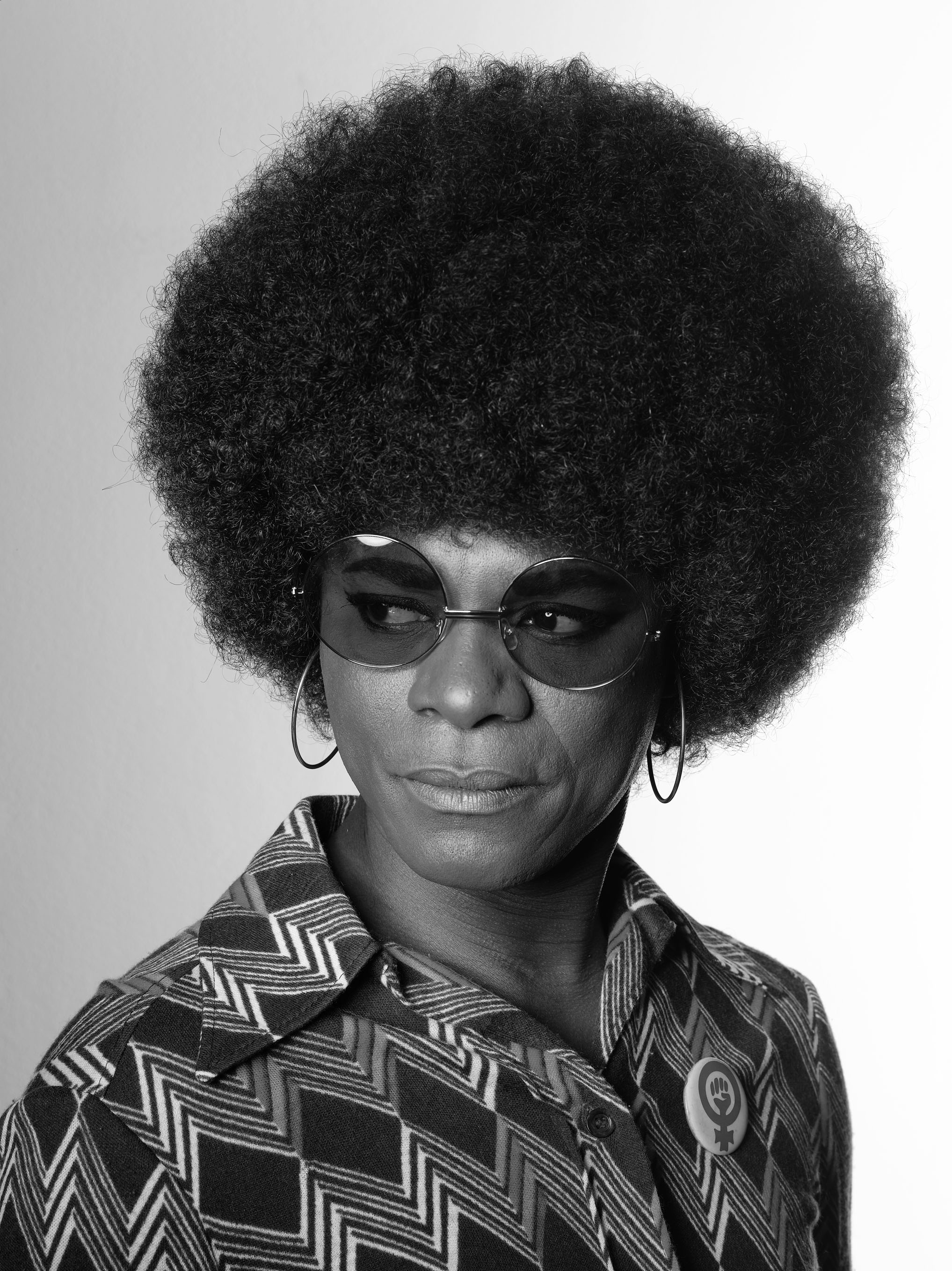

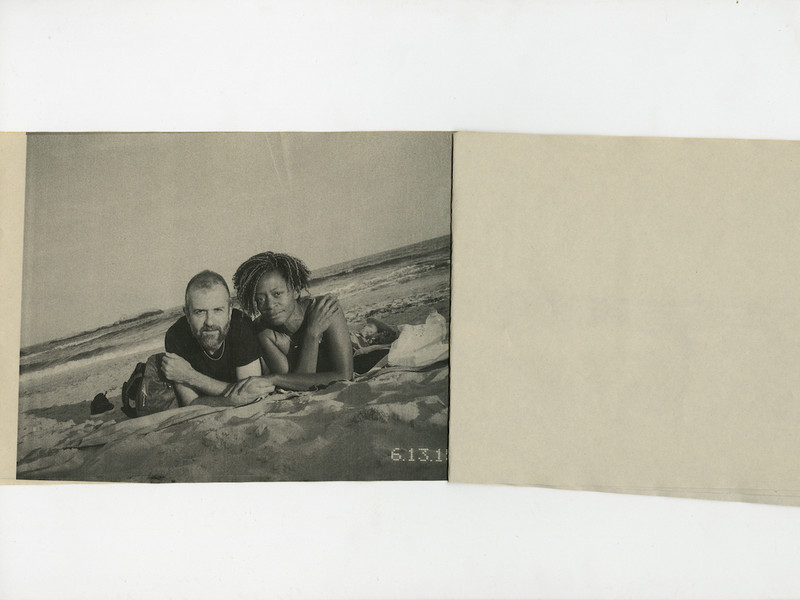

Drag became much more widely used from the 1960s, which is the starting point of the exhibition. It coincided with the rise of performance art, and with visual art’s engagement with feminism and the civil and gay rights movements. Artists are turning their attention back to drag for the same reasons: because drag is by essence performative, and is a critical tool enabling artists to engage politically with society. As well as parodying and unsettling the very idea of gender, drag is also able to reveal and undermine other systems of oppression. In this exhibition, visitors are able to track several societal changes or issues in the exhibition: feminism with VALIE EXPORT and Eleanor Antin, civil rights with Samuel Fosso, gay rights with Luciano Castelli, and the AIDS crisis with Hunter Reynolds. Ming Wong uses drag to critique the depiction of cultural and racial stereotypes, while Jo Spence, Cindy Sherman and Paul Kindersley touch on class and consumerism. In the light of current societal debates and identities, drag has become a relevant way for a growing generation of artists to take on political dimensions.

If the exhibition would have explored art before the '60s, I would have included three particular artists: La comtesse de Castiglione, possibly one of the first bio drag in my opinion, Marcel Duchamp and Claude Cahun, who created some drag king images in the '20s.

Above: 'His Majesty The Queen,' Hunter Reynolds, 1973 and '24 Heures dans la vie d'une femme/Phantasmes La Maternite,' Michel Journiac, 1974.

I do drag myself, and I often feel like drag queens are taking over the world. What do you think it is about drag queens that are so magnetic for the modern moment?

Drag queens and kings have always been magnetic, not only for our modern moment. Look at the Harlem Renaissance, in particular Gladys Bentley, for instance. Drag is fascinating because it hides and reveals at the same time, touching upon theatre, cabaret, music and fashion.

If you did drag, what would your name be?

I never thought of it! I asked my partner, who suggested ‘Bobby Cleo’.

Are there any good drag clubs in London?

Of course, London is one of the most vibrant drag scenes in the world.

RuPaul once said, “You’re born and the rest is drag.” How do you feel the show engages with this idea?

Drag allows a perpetual transition and a constant transformation of oneself. Drag kings, drag queens and bio drags not only offer a sharp and humorous parody of genders, they also question the notion of originality and the essence of social constructions. Drag reveals systems of oppressions, and proposes endless alternatives to reinvent oneself.

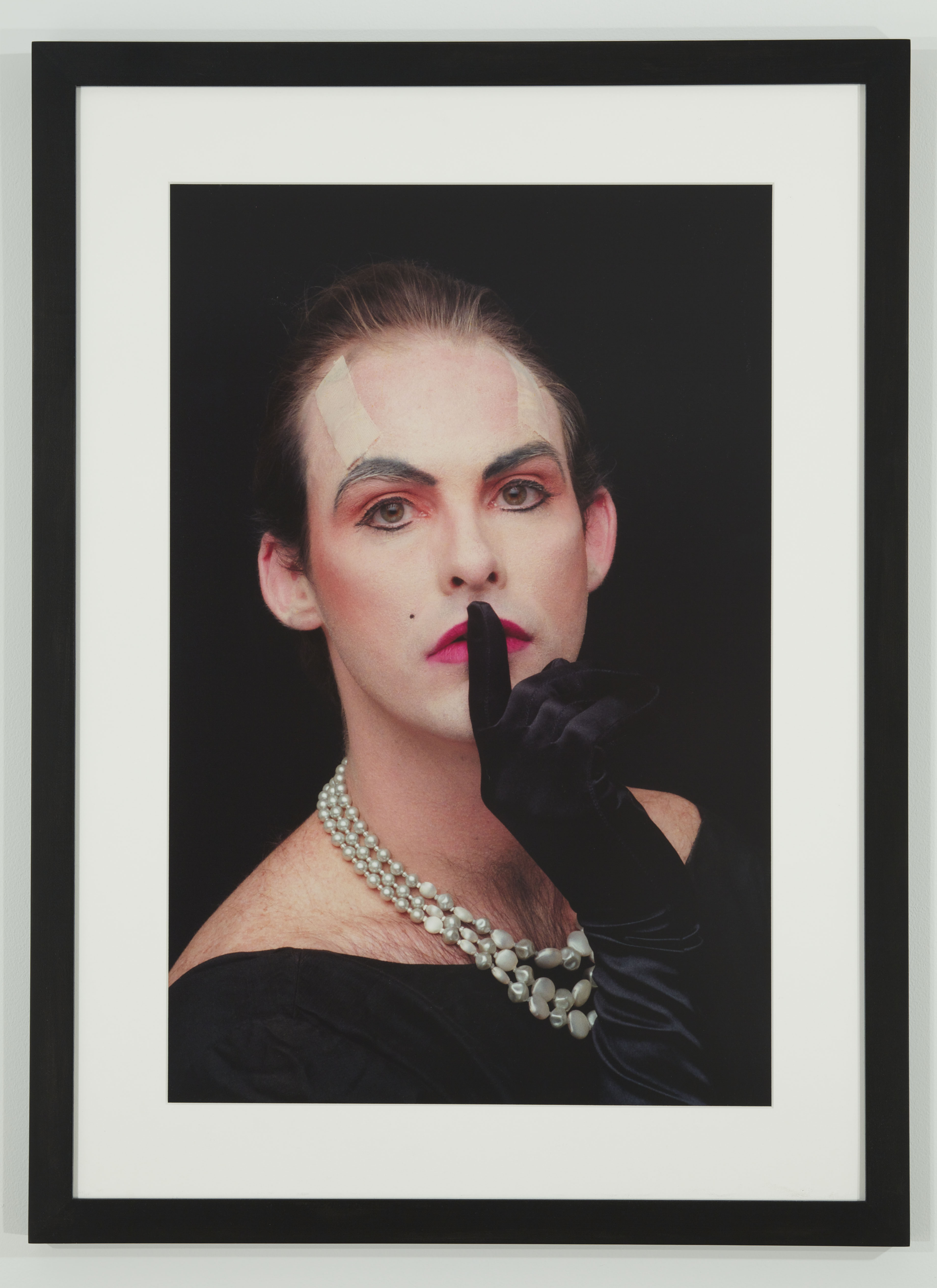

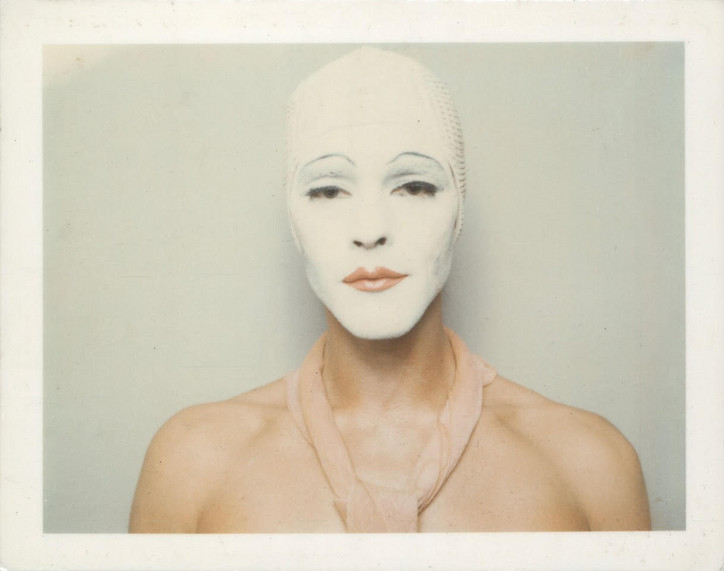

Lead image: 'Renais sense (White Mask),' ULAY, 1974/2014; all courtesy of Hayward Gallery, London.

'Drag: Self-Portraits and Body Politics' will be on view at Hayward Gallery in London through October 14, 2018.