Art & Science

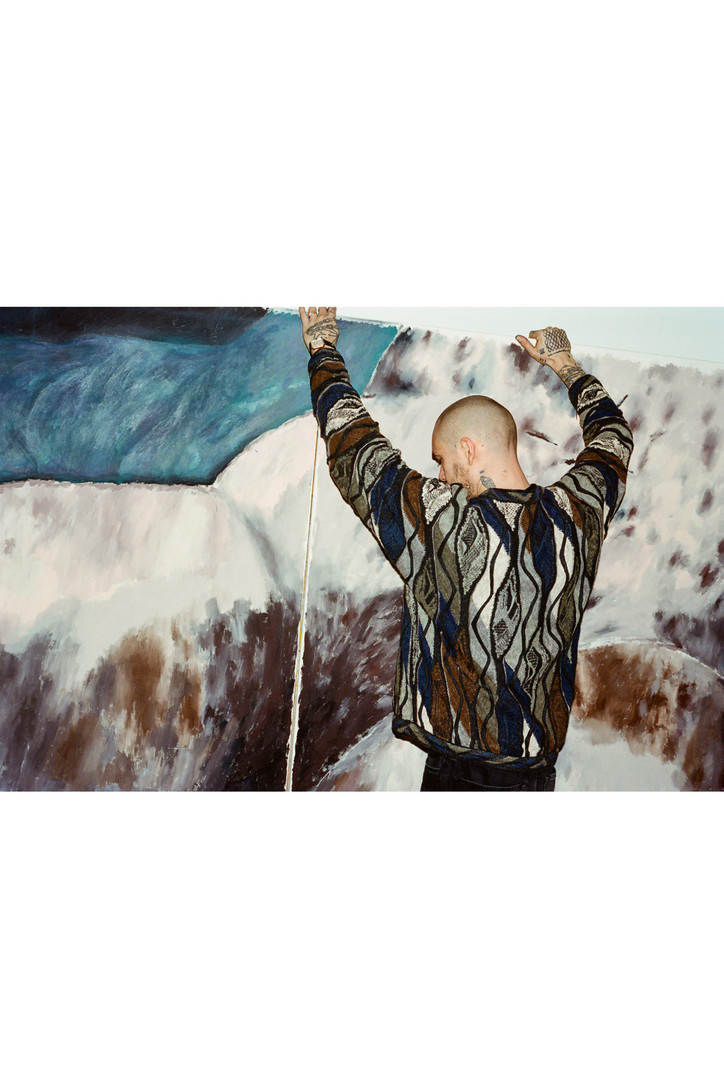

And it shows. Auerbach's art is meticulous. Whether she's working in video or sculpture, photography or paint, the San Francisco native dwells in the details, creating pieces that fall somewhere between mathematical and abstract. Her work, which is at times conceptual, is always concise; but more than anything, it pushes viewers to look past the medium or the final rendering—it's the tiny molecules, each stroke or pixel, that make up the whole.

On the heels of A Broken Stream, Auerbach sat down with office. Read our interview, below.

You've had a busy year.

It’s true. I decided to go hard this year so I could go away for a while and think.

Do you ever turn off?

I seem to have two gears, and I really need to work on having a third, more moderate gear. I’m either way on or way off. But I don’t know what ‘off’ means exactly. Maybe it means not being productive in a really obvious way, but it still isn’t really off… I don’t know. I’m hoping to explore this.

I think for creative people you're always in the process of taking in material.

You’re right. And that obviously never stops, but while I’m away I need to do something that I’ve never done before—I’m planning a survey show in a couple years I need to sit with all my work so far and try to make sense of what it adds up to, if anything. Somehow I know I’m heading into a trip where I will confront my biggest weaknesses.

Is it for a residency?

No, I applied for one and didn’t get it, so I decided to make my own.

Do you think these intense work periods are actually important for your creativity—these deep dives, going a bit crazy?

Yeah, I mean, it’s such a privilege to be able to do what you want to for a living, and then there is also some kind of demon in me that makes me need to just make things, or fix or build things all the time, so I can’t imagine putting anything less than every ounce of myself into a show or a project. Particularly if very special opportunities come my way, like painting a fireboat! Right now I'm just on the other side of a very difficult preparation period for a show [A Broken Stream at Paula Cooper Gallery], and I can't tell if I feel energized or exhausted. I guess both.

Have there been past exhibitions where you felt it was smoother?

Smoother, yes, but I have never felt that it was smooth. Ever! I have never been done ahead of schedule for anything. This show was especially challenging because a lot of practical things that came up. For example, one of the glass sculptures was broken while traveling back from another exhibition and I had to repair it in the week and a half before the show. Somehow I found myself without any time to reflect on anything. I had to make decisions quickly and so I doubted about a lot of them. I had worked for months on a new series of paintings and a few weeks before the show I couldn’t tell if they were… anything.

So, I decided to take them out of the show. I had my mind made up but a few days later I was persuaded otherwise. I didn’t even know if that was the right decisions as I was doing it, I was really uncertain about it until, like, now, basically. But I knew I was going to go through a lot of hand-wringing with these paintings no matter what, whether it lined up with outside things like deadlines or not. There just isn’t a shortcut through that time of shuttering uncertainty with something new, and in my experience, the most worthwhile things are often the most painful to deliver.

When I heard about the glass breaking incident, I automatically thought about that Duchamp work, The Bride Stripped Bare.

Because it lives in its broken state?

Yeah, because the glass cracked in transport. I forget the reaction exactly, but Duchamp felt in the end the cracks completed the work.

I wish I could have taken that approach here, but the sculpture is sort of cantilevered and it wouldn't hold itself up without the part that broke. There was no way to just ‘roll' with this one, unfortunately.

Science, mathematics, physics: these themes come up a lot in in your work. Have you always been interested in these areas?

Definitely.

Were you good at science as a kid?

As a young person, yes, but then my attention got absorbed by art. In college I intended to pursue physics, but didn’t. I don't like competition, and the science classes were graded on very competitive curves. Plus I just wanted to be in the studio. At times I’ve regretted this, but fortunately school is not the only place to learn things. I watch a lot of lectures and classes online, some of them by the people I feel I missed out on. But yes, those have always been interests of mine. I also grew up next to this really wonderful, hands-on science museum in San Francisco, the Exploratorium. I would go often, and it definitely inspired me. One of the things I like most about that museum is that everything is designed in a really functional way. The exhibits are not made ‘cute,’ it doesn't talk down its visitors, and it’s not just for kids. I still go there.

What I've also noticed is that you’re oftentimes tying science and physics to deeper ideas of spirituality or transcendence. That plays out in your current exhibition at Paula Cooper.

If you think about science long enough you inevitably run up against questions questions that generally also get addressed by theology. Being able to put these things together in a smart and human way—that’s what I admire about people like Hilma af Klint, whose show at the Guggenheim right now is totally transporting an incredible.

I felt there was so many interesting parallels between what both of you do. The geometries, the references to science, the mapping of energies. Did you know much about her before?

I was familiar with her work, but I’d never gotten to see it in person. And in person, it has a kind of aura, a charged power. The work is so effective in getting across these kinds of cosmic and microscopic structures, and in a very specific, felt way. It’s not just a set of diagrams. She talks, or the wall text talks, about a book that I have somewhere in here called Occult Chemisty, by two Theosophists—Charles Leadbetter and Annie Bessant who worked to focus their “yogic vision” to see and learn about the chemical elements. This was in the 10s and 20s, I think. This might sound absurd to some, but it doesn’t to me. I think there is a lot of information about whats “out there” that can be mined from within—we’re made up of these elements, afterall.

And what's fascinating as well is how her work existed outside of the art market.

She didn’t even want people to see it for a long time!

Well, I mean in your exhibition right now. When I look at the videos and the drawings, I get mesmerized—there’s this hypnotic effect in the patterns or the motions. It seems to suggest some kind of spiritual something.

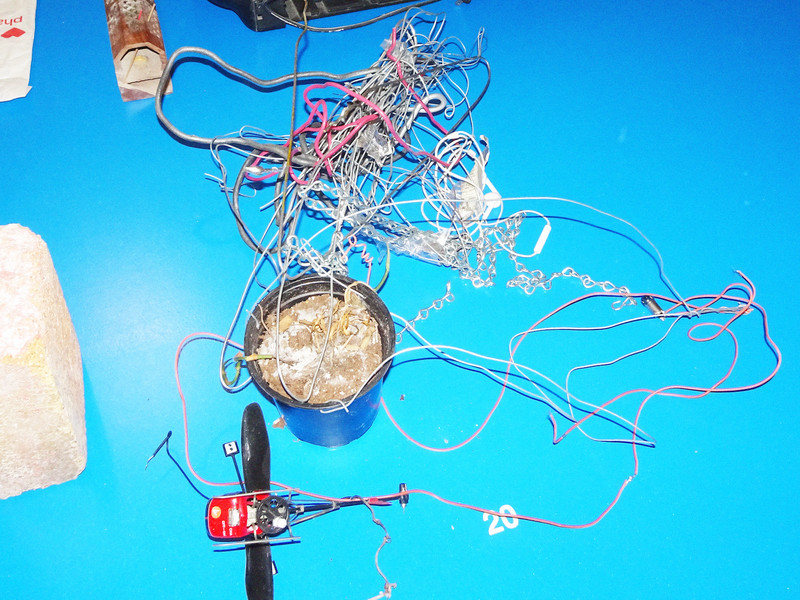

A trance state is a real thing. We get into them all the time because of like driving or scrolling on the phone. Everyone is hypnotized! These states can have a spiritual interpretation, or a purely physiological one. I personally find the droplets I filmed for the video extremely hypnotizing. For me, it was partly about getting you into a hypnotic state—delivering a kind of tremor—but also about showing some kind of reverence for the fringier or discarded theories of the universe, like Pilot Wave Theory. And despite the fact that the experiment does not prove Louis De Broglie and David Bohm’s theory, it does show us some pretty weird “particle” behavior, as this droplet interacts with its own wave.

If you look at the droplets from above, it looks like they're moving around in a way that doesn't make any sense. It seems random but weirdly purposeful, because they'll move one way and then change direction abruptly. They just seem to have a mind of their own. If you record them for a long period of time it becomes clear that they end up in some areas more than others—in rings of varying probability. The equation that describes the probability is the same as the one that describes particles position on the tiny quantum scale—like electrons and photons. So even if it doesn’t prove anything, it MAYBE gives up a taste of quantum weirdness. I want to be with that weirdness—with the qualitative features of the experiment, not the quantitative ones.

I really appreciate people’s—even failed—attempts to make sense of the universe. To me that endeavor has a spiritual flavor even if you’re a hard core, materialist. To think about everything that is, how it all connects and works, well that’s what religions concern themselves with too.

I also want to talk to you about Flow Separation, the show with Public Art Fund that I had the pleasure to work with you on, where you painted an entire fireboat. Have you ever worked at that type of scale before?

I made a curtain for the Vienna Opera House, which was physically large but it was a flat, printed surface. The fireboat was curved and we painted every bit of it by hand. It was technically a big learning experience!!!

How was that experience overall?

Just incredible, start to finish. I mean one of the most memorable, special things in my life so far, honestly. Just getting to be part of a community that I had no contact with until a few months ago has been so special. I went on a trip with the fireboat and its volunteer crew up to Albany and Waterford this summer. We pulled up next to another dazzled boat, the USS Slater, which is painted in its original dazzle, and then lead a boat parade up the river with dozens of tugs to a “tugboat roundup”. Everybody was so welcoming and kind and we all come from very different walks of life. And the work of making the piece… it was so fun and so difficult. I learned how to marble—not necessarily well, but well enough to make the design. I and I worked with an amazing, almost all female crew—a group scenic painters (Infinite Scenic). The conditions where physically very challenging and we didn't have a a lot of time, so we worked very long days. I’d kind of shuffle home sore at the end of every day, but it was the best kind of tired.

You’ve called New York home for a little while now.

10 years.

Coming from the West Coast, what what brought you here, what what made you stay?

I always thought I would be a New Yorker for life, but now I’m thinking, maybe not.

Why not?

I miss nature so much, Not being able to see a long distance, breathe fresh air—I miss that. I want to walk on dirt and learn about trees. Why do humans come to a place and just kill everything around?

I love that I grew up in the Bay Area, but I felt it was sleepy at the time that I left, and I had a lot of energy and I wanted to be in a place that had a lot of energy. So I wanted to move into the middle of it, right into Lower Manhattan, and that felt great until pretty recently. Experiences like the fireboat make me still love this place though. There are thousands of little universes in New York, you just have to discover them, and remember that yours is just a drop.

Part of the reason I’m going away for a while is that I hope I’ll get some insight on where I want to be. I'm also noticing that as people around me are having children—and I don't intend to do so myself—I am envious of one thing, which is that they have this page turn in their life, like a total paradigm shift where reality changes and a new way of thinking is required. I want to create that next chapter for myself in some other way, and to sink my teeth into a new way of living and thinking.

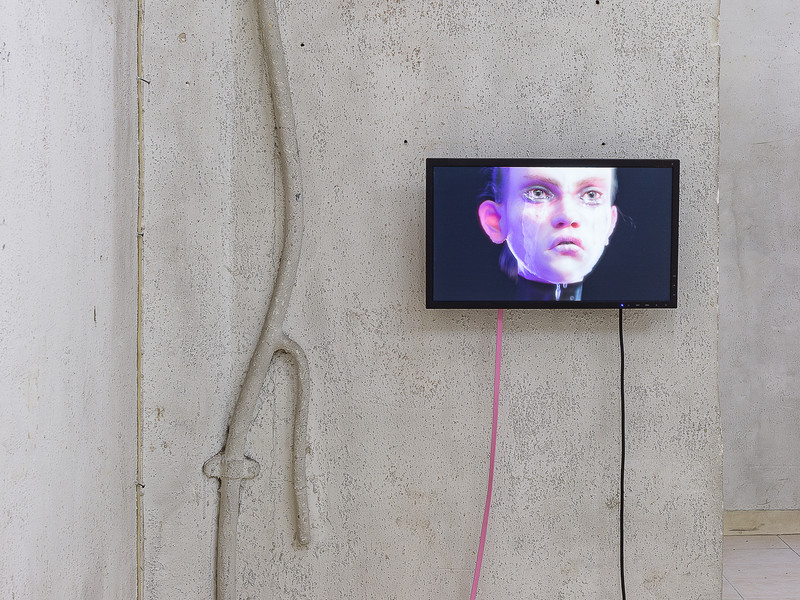

'A Broken Stream' installation view, and 'Where there had once been a snag in the fabric,' (detail) 2018; courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery.