The Pandrogyne's Shoe

The shoes themselves seem almost animate beings, their presence here a mere pit stop on their way to a land full of mystique and wonder. Needless to say, these are sculptures with layers upon layers of story. Speaking to artists on a regular basis, I often run across the concept of objects being ‘charged,’ but never have I seen such an optimal example of this idea in action. The materials in these pieces almost quiver and squirm, the organic shapes entangled with those that are manmade lends the effect of an intrinsic clash that seems to spark, rattle, and pop. There is a kind of childlike idolatry embedded in these shoes—many contain once-living animals. A freeze-dried bat rests in the sole of one pump as if it were its coffin, or a reliquary for a vampire.

The sustaining concept of a world beyond biological gender is reinforced in the use of these tiny, lifeless creatures: only an expert could identify whether the bat is male or female, and in the end, it simply doesn’t matter. To transcend biological reality is a goal humankind has been fixated on for these many millennia, and here the artist seems to reach into the natural world for a pathway to a higher plane, as well as through the simple concept of walking in another’s shoes. By projecting our minds into other worlds, the show seems to suggest, we find ourselves on the cusp of the Unknown, posed, like these magnificent shoes, before the precipice.

There is one key element to these pieces that cannot go without mention: shoes always come in pairs, yet these shoes are solo. The artist spoke of Lady Jaye often, Genesis’ other half, who left her body in 2007 (in Genesis’ words), and who shared the idea that the two of them were two parts of a whole. The other shoes, then, are missing their partners on the other side, but are not yet unwilling to thrive.

I spoke to the artist about these incredible sculptures, what they mean in regards to Lady Jaye, and the charged objects that form the fascinating story of this show.

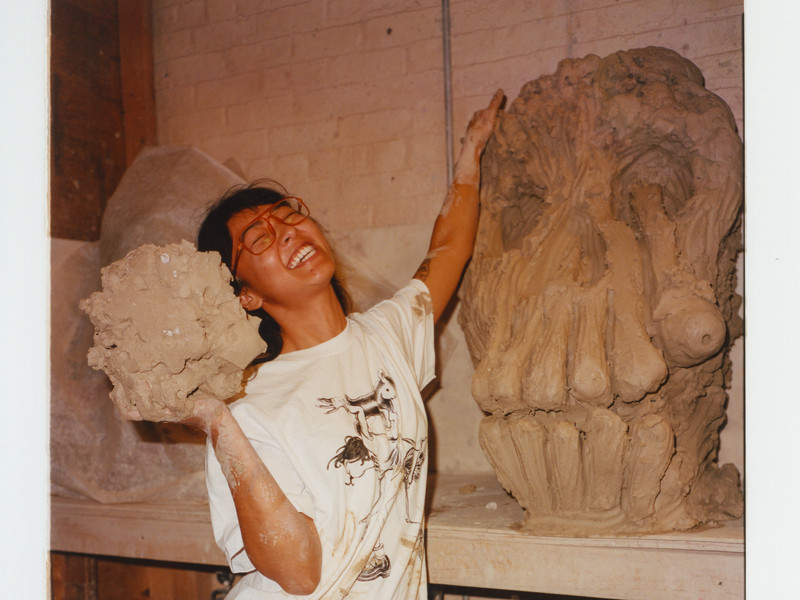

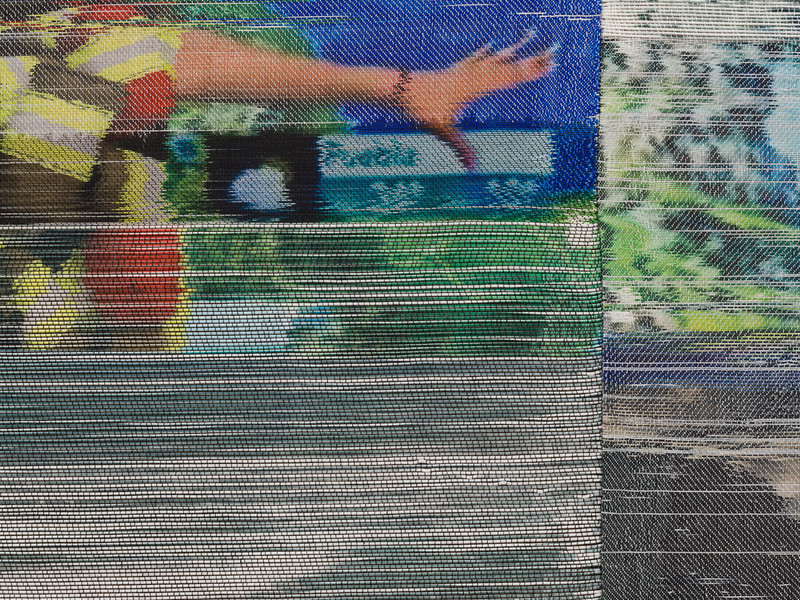

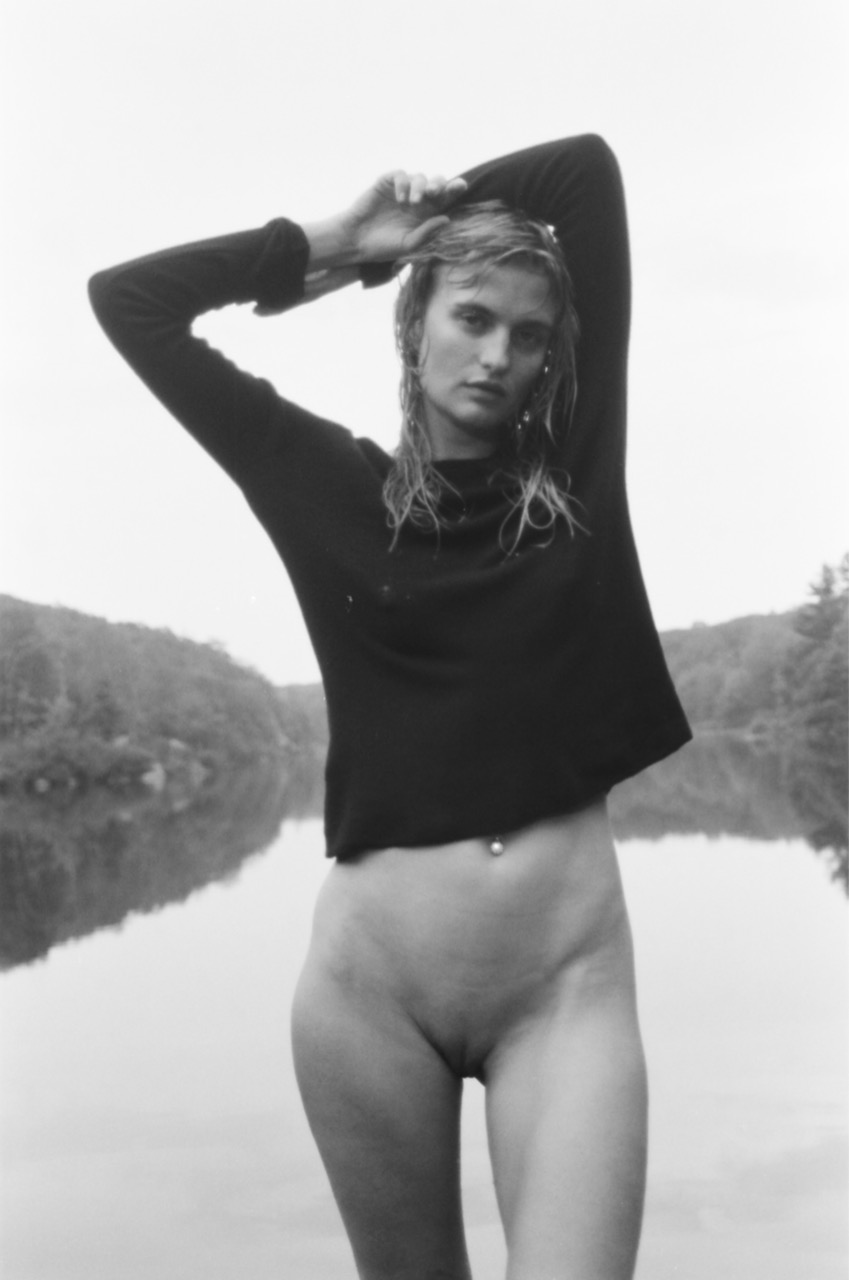

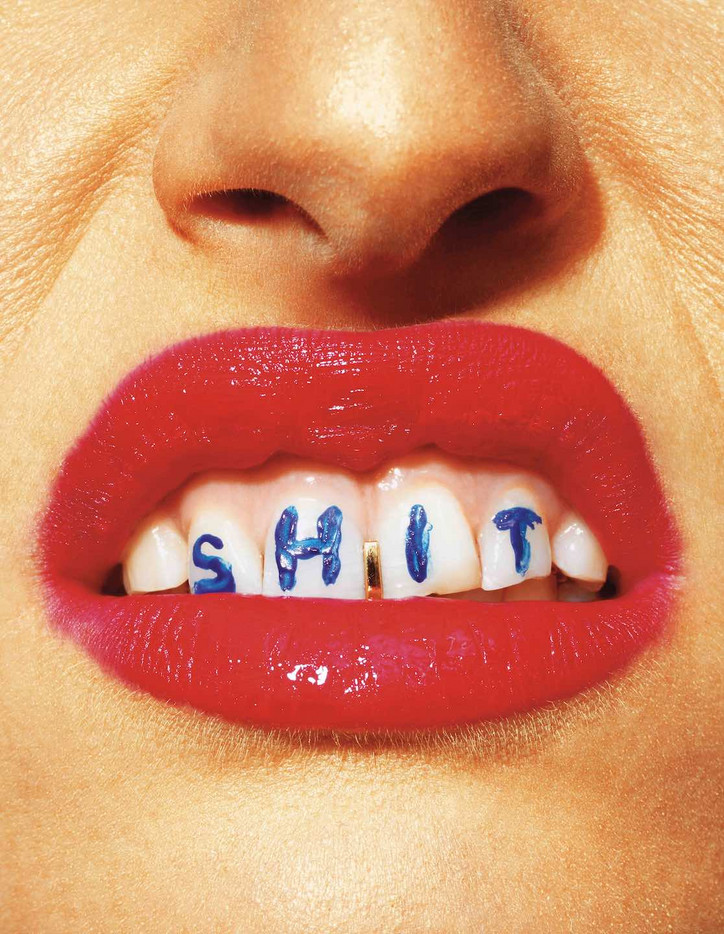

'Red Shoe for Susana.'

I love the show. Can you tell me how it came together?

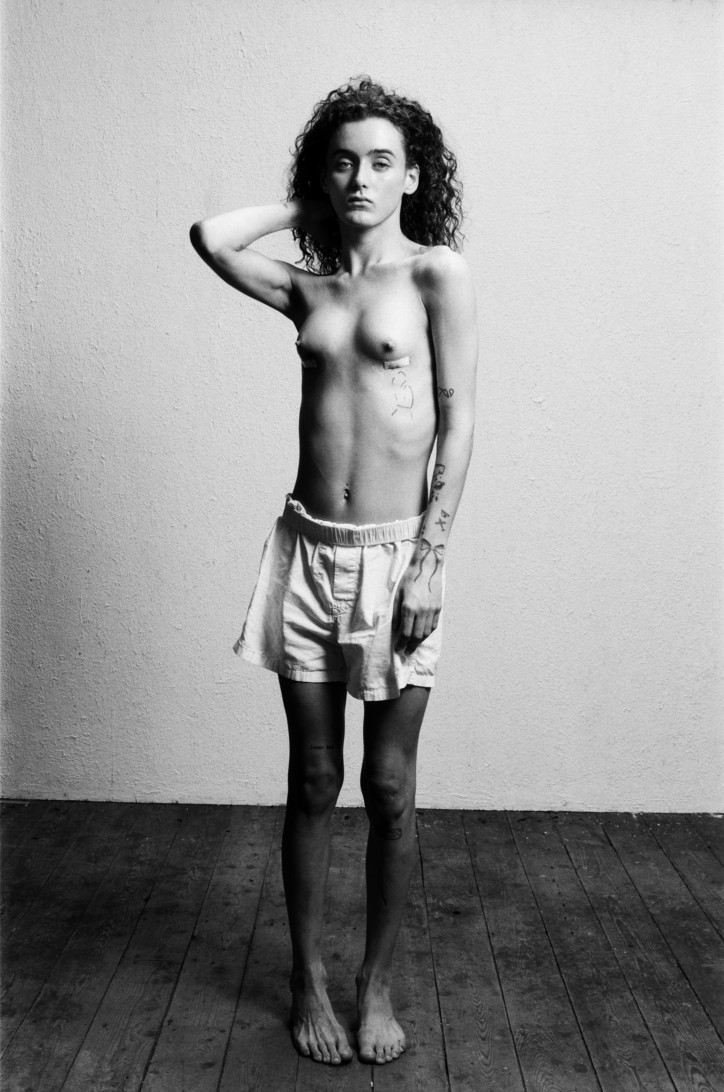

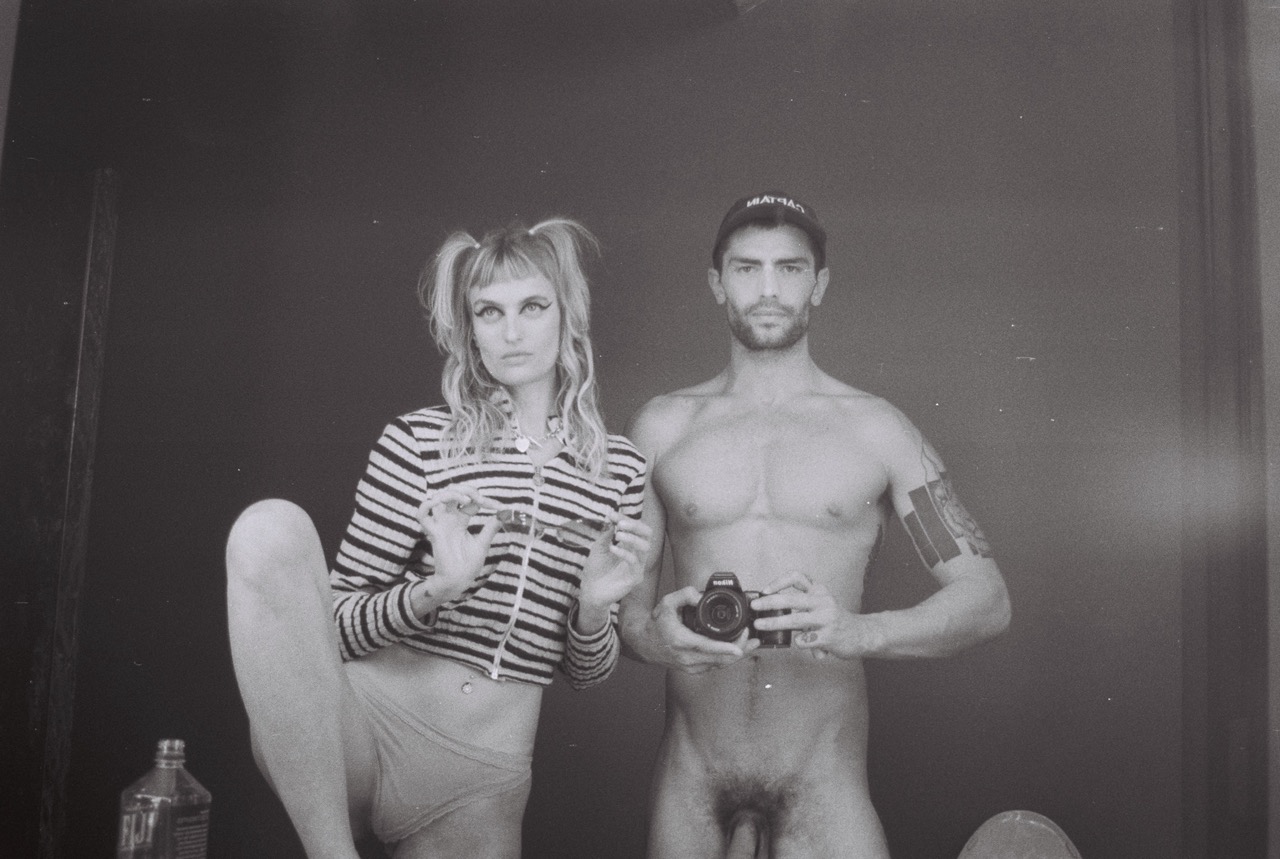

I personally think it’s one of those times when you can say: it’s perfect. Everything in it I wouldn’t change. They’re like little crystalline jewels, and it’s presented just the right way. I don’t know if you saw it when the photograph was up? But that really finishes it, completes it. There’s a photograph of myself and Lady Jaye prior to any surgeries of androgyny, but both looking very androgynous, naked, entwined. When you look it from behind all the shoes, it turns it into a shrine. It’s much more clearly a shrine at that point.

That’s interesting. I love androgyny.

That’s the basic theme, of course—the end of either/or, not just the fluidity of becoming one or another. We had a way of explaining it: some people feel they’re a man trapped in a woman’s body, some people feel they’re a woman trapped in a man’s body, but a pandrogyne feels they’re just trapped in a body. So, that’s why it’s about the end of biological perception—it’s time to totally forget about the package, the ‘cheap suitcase,’ as Jaye would call it, and recognize the self you identify when you say ‘I'—that’s consciousness. It’s not in any way to belittle the progress that’s been made in terms of identity and people like to create their own narrative—it’s that there are no limitations at all except one’s own imagination. Flesh isn’t it. It’s consciousness—that’s who we are, and it’s time to stop being distracted by stereotypes, no matter how radical the stereotype may seem. That’s something we’d been thinking about for a very long time. You said you liked it—what did you feel? I’m curious about how people respond.

I don’t even know. It’s kind of monstrous—it’s fashion meets macabre—but then it’s also playful.

That’s good, you see. It’s nonverbal—it’s bypassing explanations and ways that we perceive things and explain things. When they’re being made it’s very intuitive, it’s almost like a trance state. I don’t know if you saw what they’re made of, the materials, but all those squares of wood that have patents in them—they’re all antique blocks for printing fabric that we collected in Katmandu over the last 30 years. All the shoes have, at some time, belonged to sex workers—transexual dominatrixes, biological female dominatrixes, go-go dancers, strippers, hookers, you name it. All of them have been connected to the interplay between the sexuality, the body and desire.

Then you have all the pieces of iron, the little wiggly ones that actually represent pythons, and the ones that look a bit like umbrellas—they’re all from West Africa, from the voodoo ceremonies that I was initiated in about three years ago when we were making the documentary, where we were investigating. There’s a huge twin cult in voodoo in West Africa, so we were fascinated by what that was about and what it might be, what it might explain, because we felt that we were two parts of one. The minute we got there, the first night we were in the little tiny town square drinking beer, and I was facing a different direction than everyone else and I saw this very tall figure in blue robes and in the shadows that just seemed to float, and as we were looking we said out loud, ‘I think that’s a priest,’ and everyone turned round, but they’d gone, vanished. Then the next day our guide said, ‘Would you like to come and meet our family for dinner?’ so we said, ‘Yeah, of course,’ and we went to their house on that side of the compound behind a wall in the town square—so it wasn’t magic, the father was very tall, he was the high priest of all the voodoo there, as it turned out, and he’d just gone in the gate, but we couldn’t see that in the shadows. So, it wasn’t so mysterious. Then he looked at me and he went, ‘You had a twin, but she died and you’re wearing her gold earrings.’ My hair was down so you couldn’t see my ears, and I was wearing Lady Jaye’s gold earrings. And we always saw each other as the other’s half, as twins, and that’s when they started to initiate me into the twin cult and the python cult. So, all those bits of metal are from that trip, and that investigation. That was three or four years ago, it was over a whole year, the documentary premiered at the Rubin.

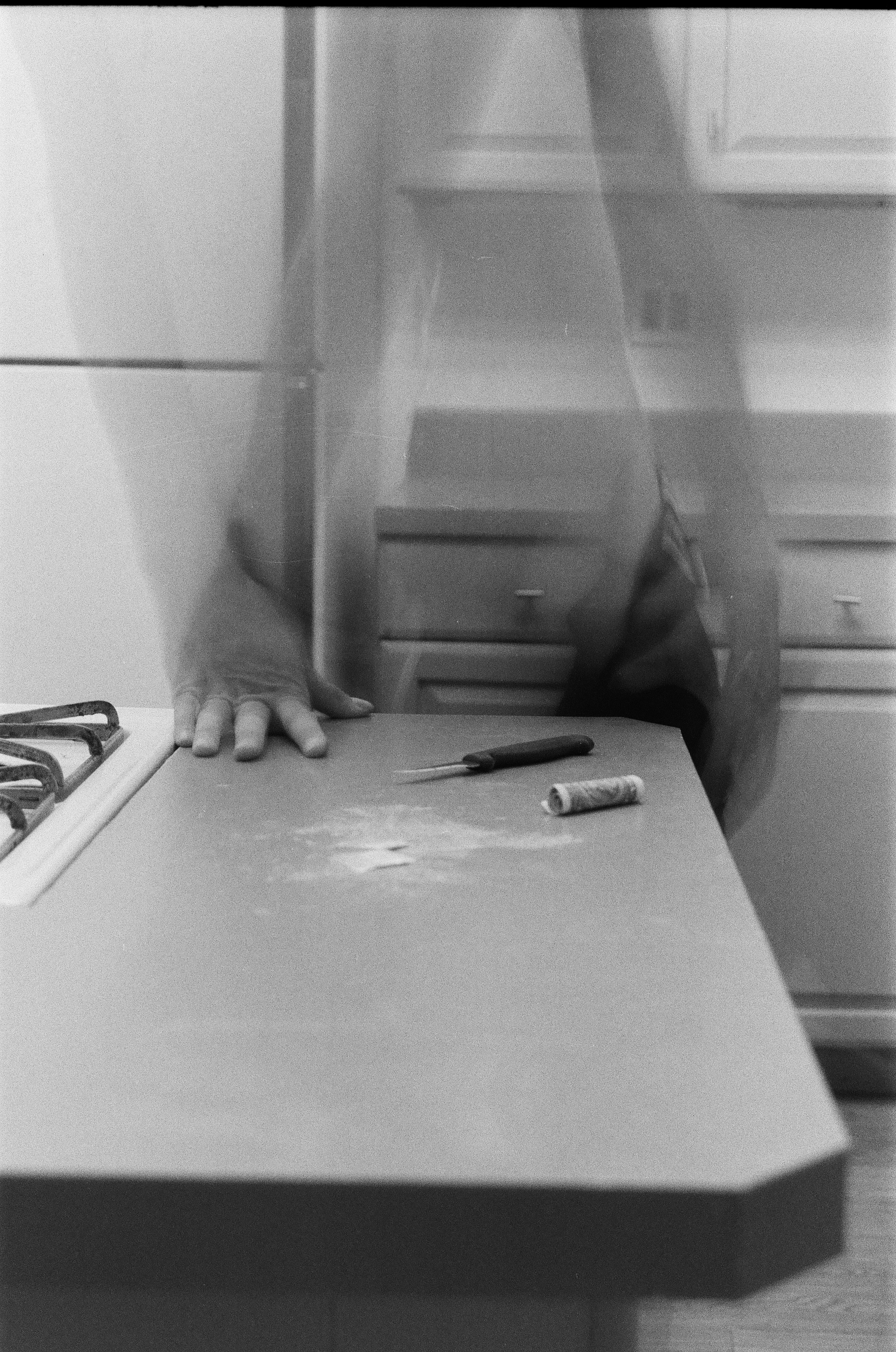

I don’t know if you noticed all the little fish, but they were from our fish tank. We’d put feeder fish in for the other fish, and when they died we’d dry them out and keep them. So, everything is little fragments of ritualizing daily life, which made total sense when we were in Africa, or in Kathmandu, with the different tribes of that part of Africa, that’s how they view life—there’s no separation between mystery and mundanity. It’s all interlinked. You can be walking to the office in your office clothes, and literally we saw a woman stop and sacrifice a goat, then carry on to work, and no one looked at her because it’s a part of daily life—this mystery and nonverbal communication and devotion are all absolutely integrated into everything that happens. Domestic or banal objects can actually have great significance if you know more about them, and that’s kind of the root of what we were doing with the show. And shoes are just such a wonderful thing to work with, because they’re already a fetish.

Lady Jaye was your partner?

She was my other half, yeah. She left her body in 2007. She was a professional dominatrix and a registered nurse, so her whole life was about the human body and the tensions of fixing it, and attacking it in a way—that strange combination that people have.

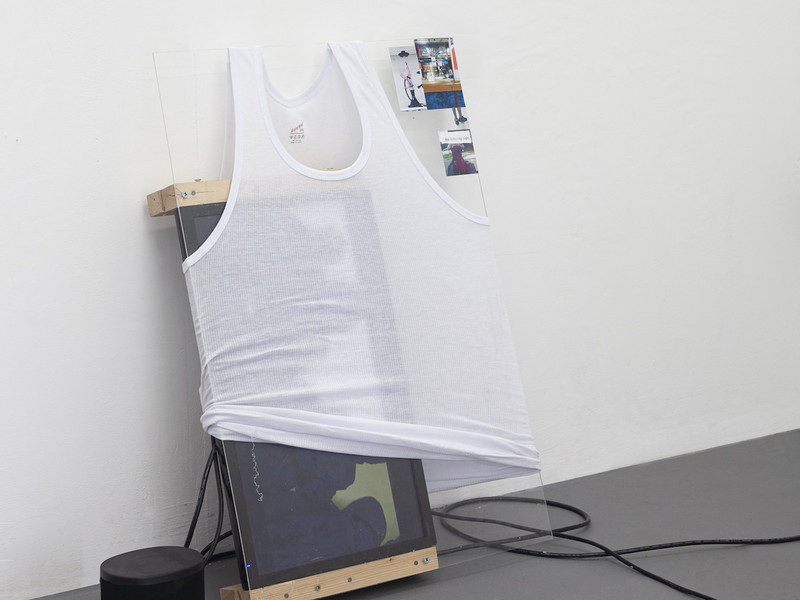

'Shoe Horn 7' and photo of Genesis and Lady Jaye.

So, that’s how you acquired all these shoes?

Yeah, exactly! Later on I started working as a transexual dominatrix in a sex dungeon, too, my name was Lady Sarah—a very strict former English school principal.

You were a dominatrix?

Yeah.

Are any of the shoes yours?

Some of them are, yeah.

I love the taxidermy—well I’m not even sure they’re taxidermy, but I love the use of animals.

There’s a freeze-dried fruit bat in one of them. Isn’t that strange?

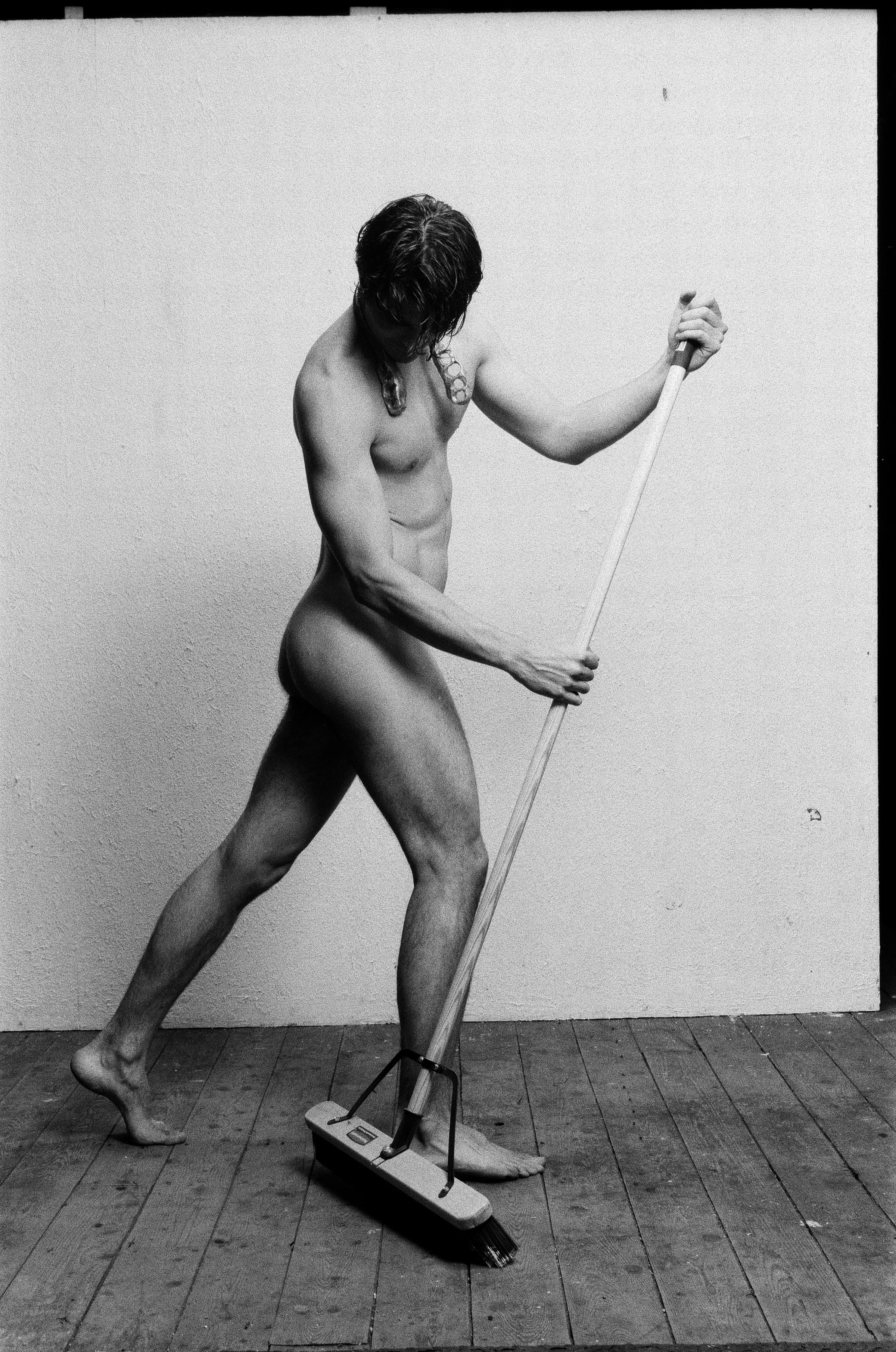

'Shoe Horn 3.'

My mom would keep things like that all the time. She had a bat in a little box for a while that she’d found in our garage. We had a lot of taxidermy in our house, so I totally relate to this fascination with preserved animals.

There’s a box as well in the show, I don’t know if you saw it, but all the little papers inside are all genuine heroin bags from the '80s and '90s when they used to give them all special names for branding. So, all of those are in there, and then the little gun, which is a genuine antique pistol, I’ve had that since I was six years old. My father gave it to me when I was a little kid—I used to collect antique weapons. I’ve kept it all that time—for 60 years we’ve held on that, and of course played with it when we were little, and kept it because it’s association with childhood. Then finally it was ready to be used, and it became part of the box. And the two little statues are twins from West Africa, and if you look inside you’ll notice each only has one leg. And we asked about that and they said it’s because they’re only whole when they’re together, which is what myself and Lady Jaye felt—that we were twins and we were only complete when we were together. We were each half of something—something spectacular that could only exist in the union of unconditional surrender.

It’s almost like a time capsule.

Yeah, of course. In a way it’s a journal, almost. Everything within it has been a part of our lives, or has different effects, or represents different times when our ideas changed, or our perceptions adjusted because of new information, or wisdoms we might have collected. So, each one is that encapsulated. They’re almost hieroglyphic. It’s like when you couldn’t explain how you felt about them—that’s what we want. We want them to be like Mayan hieroglyphs—something you look at it and go, ‘I know this is significant, I know this has a lot of thought behind it, it’s the purified essence of all different kinds of lines of thought and different ways of seeing the world and using perception, but I can’t read it, I can only feel it.’

It’s also an interesting comment on fashion. I always think when I see something crazy in a thrift store or a shop, I want to meet the woman who would wear that. I feel that about this show—I want to meet this woman who’s wearing these shoes. You can’t really wear them, but it’s like a fantasy—it’s almost like a goddess.

Right! Absolutely. We have a real belief that objects absorb some kind of energy from the people who keep them and the way those people revere them and what they usually represent to the world outside. You’ll find most people keep things—pebbles and shells from beaches, or bits of driftwood, or like you were saying, taxidermy, things from childhood, little dolls. People all respond to those things, but they’re somehow trained that they have less intrinsic value, when in fact for me they have the most value, because they have an unwritten language that connects everyone. You could take one of those shoes to the Amazon and they’d be equally fascinated by it, the feathers and such. It would still reflect and resonate. You could take it to Kathmandu and the shoe is a religious object, or a shamanic object. It’s a sort of universal language that we’ve often had diluted in the West.

There’s also the satirical reflection of fashion as well. The shoe is an impossible item—why do people wear high-heeled shoes? It’s a ridiculous idea. It’s uncomfortable and difficult—you can break your ankle if you slip. And yet there’s this universal obsession, as well. I wanted to look at that: the impractical but the desirable.

I feel like I’m still reeling from the voodoo element you were talking about. You’ve clearly traveled quite a bit—did you go specifically go for artwork or was it a part of some kind of research?

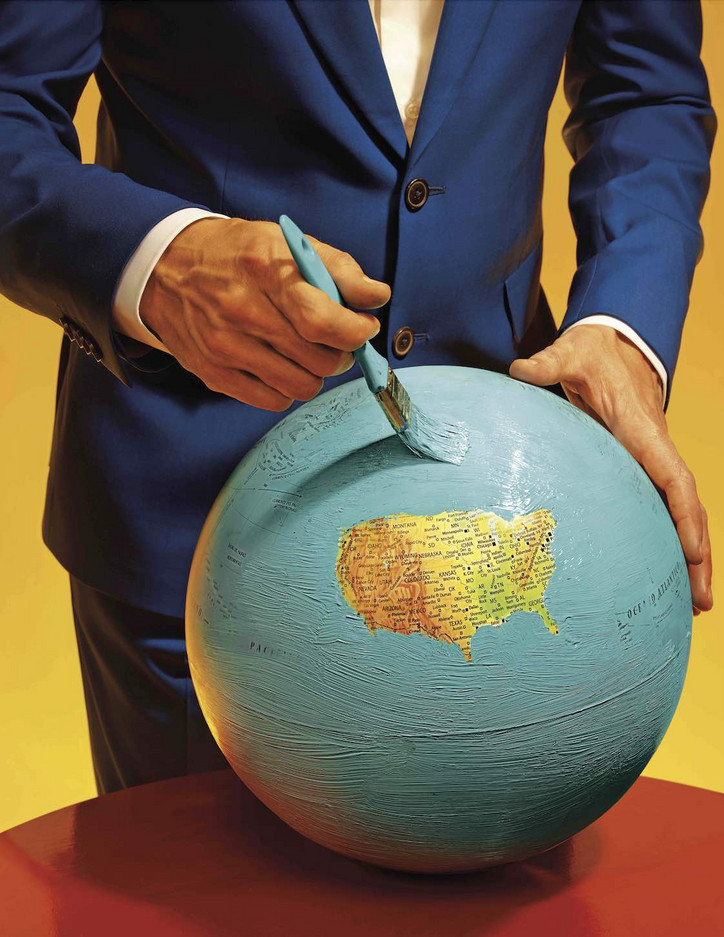

Research for everything. I often give talks at universities and young students will say, ‘What can I do to have a life like yours?’ or ‘What can I do to be more expansive in my ideas?’ and I just say, ‘Travel! Get out of the United States and travel! Go to Africa and see what poverty really looks like, people who live in one room with a dirt floor and feel blessed that they can eat that day, and they’re not complaining because that’s normal, that’s a good day.' Just to get a sense of proportion. Everywhere you go there are traditions and stories that will teach you things that you won’t learn from the established culture, because it wants to remain established—it wants to remain the main culture. So, to break away from what you’re expected to use as a reference, you have to travel and open up the mind to all sorts of possibilities of addressing the mysteries of existing. That’s why we travel.

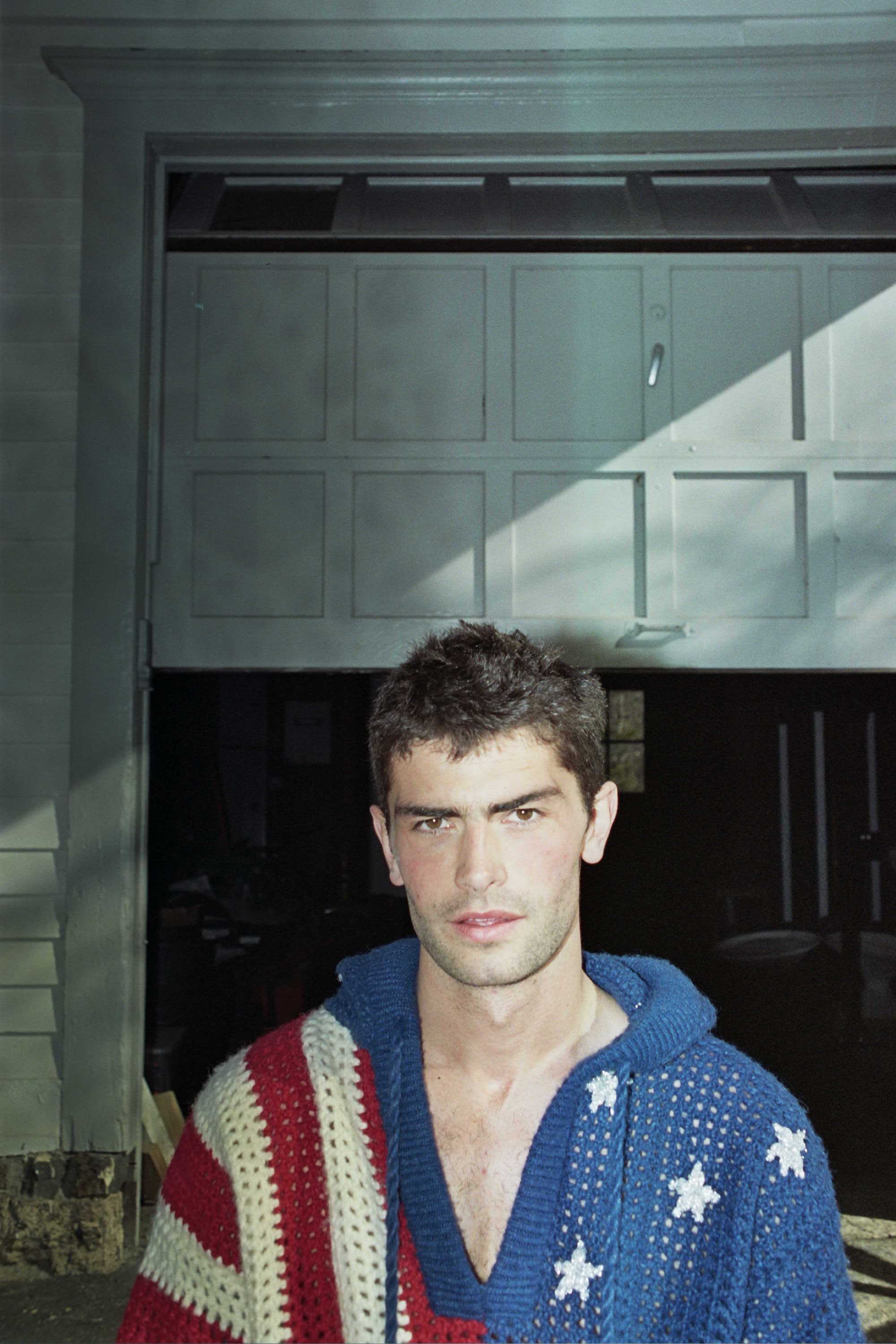

'No Mercy.'

It almost seems like your show is about that—the objects are collected from so many different places.

That’s why I said it’s very much like a journal, as well. It’s an act of faith, in a way, that something will be communicated through the interaction of the different items when they’re put together—that it will speak, and I really think it does. The response has been incredible to these shoe sculptures.

They’re really approachable, I think, too, because everybody wears shoes.

There’s a glamour to high heels, too. There’s been a resurgence of a surrealist approach to fashion again recently, as well. A lot of the young designers and photographers are doing a lot of things that are post-Leigh Bowery—very impractical, but incredible visually. They’re not made for everyday, they’re made to literally blow your mind for a moment. I think that’s really healthy and exciting.

I think there’s a return to decadence right now. I don’t know why, but I love it—it’s like, we don’t need this at all, but we do.

We’ve just been involved in a publication online and, I think in print, of something called Dazed Beauty. It’s connected to Dazed and Confused, and it’s dedicated to post-internet, post-technology versions of things that might once have been called glamour, or beauty—people who are interfacing with technology. So, they came to us to be one of the four people on the cover—they’re doing four different covers—because we’re one of the trailblazers of anti-fashion fashion. It’s like suddenly everyone has become Leigh Bowery on ketamine.

But with the shoe sculptures, I can’t really leave my apartment very much at the moment because I’m sick, but I have a little row of black boxes above my bookshelves full of strange little items, and I just made the sculptures out of what was here. It was all here. It was like, this is already in my life. All I did, really, was collect it together and let it coalesce. It was so much fun creating them. It was like, 'There’s a shoe, what’s gonna happen with that shoe? Which of these horns is gonna go with it, and which way?' It was really quite incredible to produce an entire show in one room on the Lower East Side without leaving.

These were all just things that were laying around? Wow.

We were in Wales about twenty years ago and they had a big box of horns, and I said, ‘Just buy the whole box, they’ll be useful some day.’ We held onto them all the way through moving to America and changing houses and homes, and now there they are, all being used. Of course, what happens next, when all my shelves are empty, I don’t know.

'TOWARDS AN END TO BIOLOGICAL PERCEPTION' will be on view at Marlborough Contemporary through Febrary 16.

Lead image: 'Shoe Horn 9.' All images courtesy the gallery.