Urban Imprint

I interviewed Inglessis at A/D/O, where Urban Imprint is installed in the courtyard and open to the public. We spoke before it was open, and thus I had to return in order to experience it myself. Essentially it is a strange little pathway that moves around you as you walk on it, the weight of your feet absorbed by the spongey pathway, and the ceiling, connected to the floor through a network of wires, lifts away from your head as you walk—it’s as if you were in a bubble traveling beneath the sea, except the sea is a metal network meant to imitate and critique a hard floor and stable ceiling. Frankly, it must be experienced to be fully understood, which is why, after speaking with Inglessis, I felt the need to walk around on it (in it?) myself.

Can you talk about the work?

The piece is called Urban Imprint, and it really came to being, we were contacted by the team at A/D/O who put up an installation for NYC design week, and the theme was how we look at our future self and urban environment, and one which is tethered more to nature, our human nature, and that’s not in conflict with it. That was a great question as a starting point for us, because everything we do in the studio is about redesigning our physical environment, to make it more interactive, more dynamic, so that we, cognitively, are closer to it and more in tune with it. So Urban Imprint is an evolution of our research, which we call is that of an augmented materiality—the idea, from an augmented reality or virtual reality, the idea that technology can be used to embed new capability in the physical and tangible and doesn’t necessarily only have to focus on the idea of simulating a reality or creating basically a dystopian future where we live in a headset. I think there’s a lot of ground to use our new tools, such as digital fabrication, to redesign the physical, and Urban Imprint is such a redesign.

We’re taking over the courtyard, and reimagining what an urban environment could be like if it wouldn’t be static, if it wouldn’t be pre-defined, and wouldn’t be something that we move around, but rather that the space forms around us. So it is a completely human-actuated installation, it’s kinetic, it is analogue, although we’ve used computational design to form a lot of the materials, we used traditional mechanisms, so it’s a combination of new and old, but the result is that it doesn’t require any power, it only comes alive with the visitors. The floor recedes, the roof opens up and you have a transformation of both form and light, so the space will always be unique to the person within it. That’s why it’s called imprint—it’s this idea that an urban environment will form around you and you will leave your imprint inside it, so I felt that this brings us closer to how we interact with the natural environment. If you think about how you are in a field in the woods, because a natural environment has taken its form from the needs of all its living elements, you’re always going to be in this passive interaction, where you’re going to be leaving your imprint of walking in the grass or if you open a pathway in the woods—an interaction that makes you feel that you have an impact, that you’re shaping your environment, makes you more attuned to your presence, and also makes you feel that you’re part of that ecosystem, you’re part of the shape and the form that this takes.

In our current urban environments, it’s the very opposite of that, it’s like somebody has poured us into this vessel of concrete and glass and we have to navigate a design that’s been given to us. The Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, who wrote Delirious New York, has an amazing quote that says ‘the future of urbanism should not be about definitions, but about endless possibilities.’ It should be about, really, a flexibility that’s more in tune with the diversity of our psychological self, and our needs. So both bringing it closer to our human nature and our natural environment, Urban Imprint is sort of a live experiment in the physical form of very new and different urban environment. The space almost becomes an extension of your own body.

So the space moves?

It moves under your weight, your movement, your presence. It becomes a bit like a large architectural exoskeleton. But also, as you have different people within the space, their presence will also effect the form, because each person will create sort of like a cocoon around themselves, the space basically transforms. Digital tools have been used in its design, as I said, we’ve used steel and created a computational pattern that allows something as rigid as steel to become almost like a malleable fabric, a mix of concrete and rubber, so the materials have been formed—we’ve used technology to reform the materials—but the actual, final design, doesn’t have any censors, doesn’t have any digital signaling interrupting the interaction. It’s your body directly impacting the material. So it creates that very direct link between you and your physical environment, which something I’m very passionate about because it’s where I believe, when I talk about an augmented materiality, that these interactions, which are so rich and can tap into all of your senses, can be formed. We don’t always have to go to the digital or the intangible to get that, we can enhance and make the architecture of our physical environment more dynamic, which, if you think about it, we’re still far behind, it’s still quite static, we still have to demolish a building to create a new one, it doesn’t adapt to evolve, this table is still a static table. I think that we have so much new capability now, and that has opened so much room to reimagine how we design our physical environment.

It’s such a weird, crazy idea of architecture. Where do you picture this existing in the real world? I guess everywhere?

The way I see this and a previous work called ‘Disobedience,’ which was a wall that was flexing, these are sort of archetypes and examples of use material, structure, mechanism in very new ways, and creating these very dynamic, and very tangible physical systems at an architectural scale. It might not be a complete design solution in itself, I’m not portraying an evolving house, but I see installations as an output of our research and almost an informal experimentation platform where I can actually observe the interactions of visitors, of people, with the piece, and that’s what always completes the work. And that advises future research, which is really finding these elements in application could inspire architects, could inspire designers, could inspire engineers to incorporate that in how we build our buildings; these are elements that could then be combined to rethink the future of architecture.

The Japanese had a movement at one point called the Metabolism, it never really worked but it was this idea of these capsules. They had this idea of how architecture could be an evolving thing, an evolving organism, looking at this with a new lens. As I’ve said, taking elements from the natural environment and how we interact with that, these dynamic behaviors which can be integrated into our architecture, could create possibilities for our living spaces to be much more in tune with our human nature, with our need for interaction, but in the real reality and not just in a headset or on digital platforms, but also more in tune and symbiotic with the natural environment, because so far the static nature of our architecture and physical design environment looks at our living spaces as a boundary—a boundary of human to human, a boundary of human to nature. When I look at the structures of Urban Imprint, we almost have a skin that opens up, flexes open—we start by looking at dynamic forms that can take any shape and that can also be permeable, to allow more for an exchange. Also for a space to be something more personal, and a bit transient as well—it always takes a different form.

You keep mentioning the digital as being an escape. How do you view this in relation to the digital?

It’s interesting because my journey, my education took me through a lot of computational mathematics, design, I’d already studied as an engineer at Oxford University and I focused a lot on what we call control engineering, which is a completely intangible and digital analysis of how the world works. And then after going to the Royal College of Art, I then went to MIT Media Lab, where as a visiting researcher I could see how much energy was being put into these intangible realities—simulations, virtual realities, augmented realities. But at the same time, I could see this computational power gave us so much new capability with how we combine materials, how we could fabricate them, how we design, how we can simulate physical systems. I felt often that we’re being pulled to try and replicate something that is so rich, which is our physical reality, rather than enhancing it. We are slowly going toward this idea of living in a simulation, living in a headset, and I felt the need to explore what I felt was an unexplored space in actually using the digital world and digital capability to design something physical. Somebody could argue that if a simulation is exactly like reality, why not? I feel we’re not there yet—we might get there, I also feel in our digital platforms, at the moment, we don’t get as much sensorial… you can’t get the richness of all your senses being triggered at the same time as you can in the real world.

Unless it’s like The Matrix.

Yes, which we’re not there yet. Why not try and build this reality where we do have that? We already have seen that to some extent our digital technology has fast-forwarded so fast that we haven’t really had the chance to understand the right interaction with it, which is sort of within our nature. We say often that you get an overload of information, your senses get overloaded, we’re constantly in this conflict where all our devices are more of an interruption into our daily lives, rather than something which is enhancing or being symbiotic with it. There is that tension—this digital world we’ve created still needs to be refined as to how we interact with it so that it’s more within our nature, and I feel that it shouldn’t necessarily be through a device, it should be through an interaction with matter, with the physical, with all our senses—we see, we hear, we touch, that’s how that interaction should come through.

I love that. What do you feel our nature is? What do you feel that you’re tapping into—I get into arguments with my friend about this all the time, but what is human nature?

You have to start, really, from cognition, which is sort of, on one hand, how does our brain work, in many ways, and I often go back to reading a lot from Marvin Minsky, who was one of the founders of artificial intelligence, and how he drew upon how humans think to create constructs of intelligence. But how our brains works, our brain works in a particular way, but it works within our body, it gets information through our body, which is our tool of sensing the world.

So I feel that our nature is one where, the way we receive, digest, and sort of provide information should be through our whole being and our body in all its capability as it can sense the world, right? In a way, I think that a purely digital platform is not doing that, it’s tapping into our vision, potentially our hearing, but it’s not engaging our full capability of understanding and sensing the world. I also feel that there’s a lot that we can learn from nature and also what is our part, how do we fit into the natural environment as well—which we have, in many ways, built constructs and designs, human-made constructs, which as I’ve said are more of a boundary to that. We often in a city can go for years without engaging with nature, and there are cities where there’s not even a park in the vicinity. I think there are elements—they say even in psychology you have the fight or flight mechanism that’s still within us—there are elements that are natural to our biology which we’ve put ourselves in environments that don’t tap into those at all, our interaction with the natural elements, with an ecosystem that has other living organisms in them.

Those two bring us back to the need to re-consider and redesign. I also feel there’s a third element, which is the nature between humans, of communication, and that some of the constructs we design, on one hand expand the realm of communication, digital platforms and the rest, but again, they create forms of communication that are not multi-sensorial, they’re not physical. We talk about the age where touch between humans won’t exist—think about that. The physicality is leaving, the tangible part of that is leaving, so that’s why I keep, in my work, I keep trying to pull us back to the feeling, to the touch.

You say about human nature, becoming a mother you hear all this advice, one thing people talk about a lot now is the newborn has to have skin-to-skin contact—the first thing that has to happen when the baby is born is for them to feel your skin, and it’s really important for their development and the psychology of a baby, and to have certain hours of the day where they’re not touching your clothes but it’s actual skin-to-skin. You think about if that’s so important for a newborn, why isn’t it important for humans throughout their life?

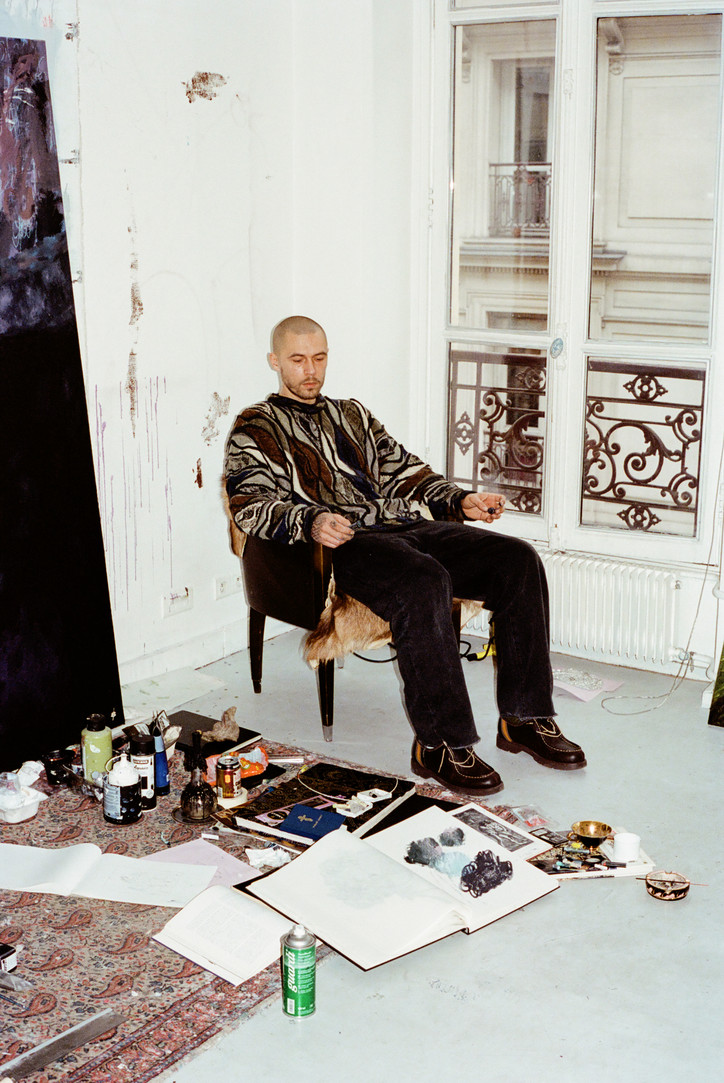

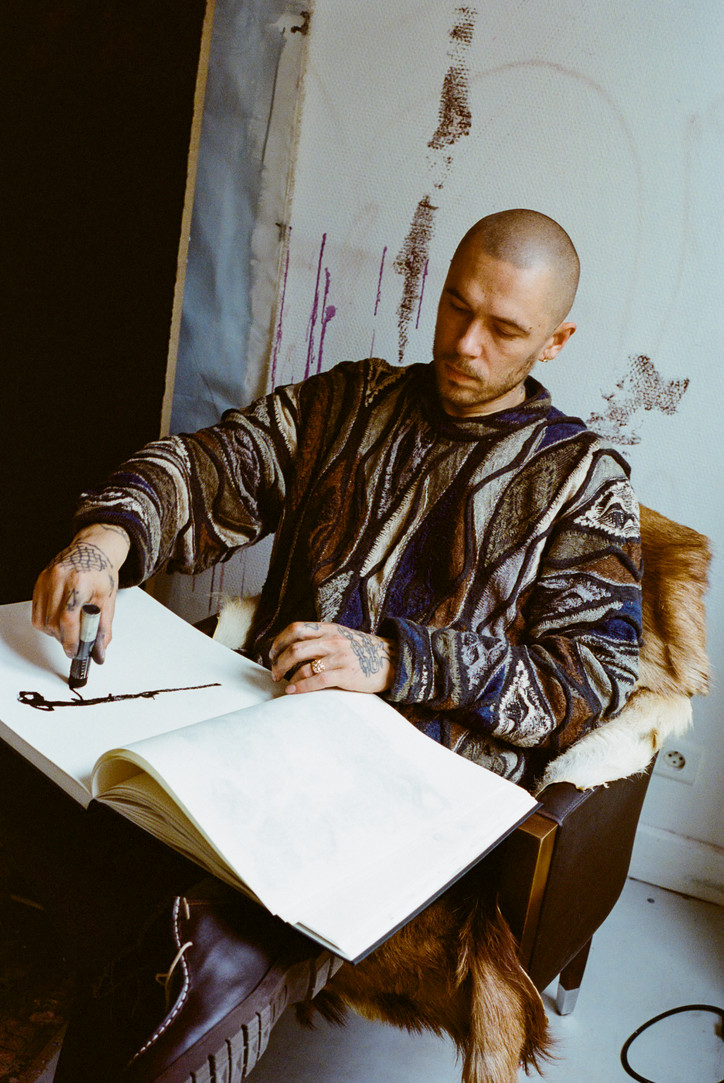

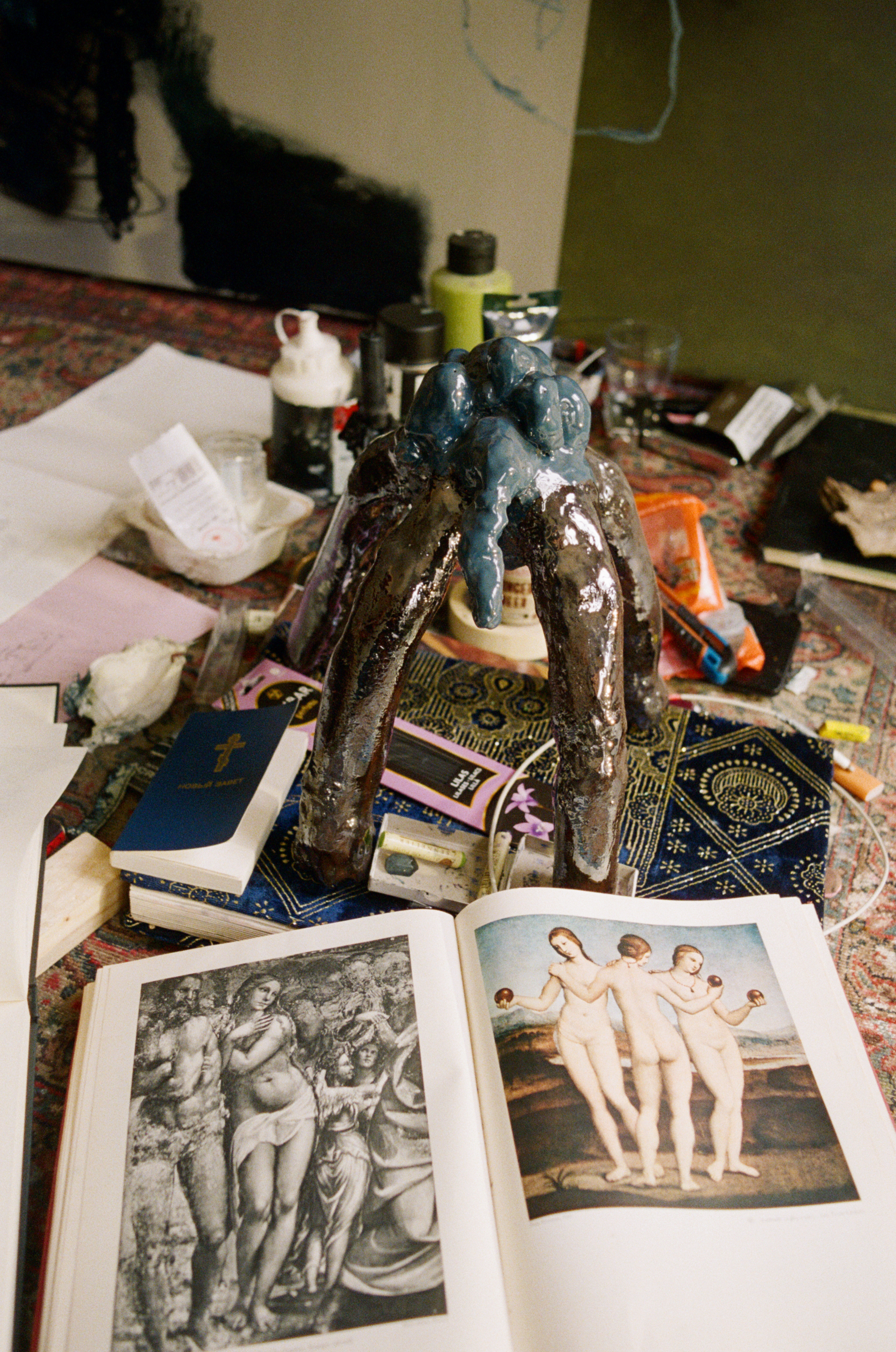

Above: Iglesias working on 'Urban Imprint'

I can’t believe that’s even an argument, that that’s going to happen. Maybe it’s a philosophical thing.

Think about it, though. Now, especially, there’s a lot of social tension about how people work together, about how people interact together, you know.

It’s funny when you were talking about communication and digital platforms, I do know exactly what you mean because there’s so much that’s communicated through tone of voice and body language and things like that, and you type something with sarcasm and it doesn’t translate. I can’t tell you how many arguments I’ve heard of people getting into because of just misinterpreting an email or whatever—I had a friend who said, oh I meant this in a joking way, and I told him you have to use words to communicate that you’re joking, or like emoticons. Emoticons are my favorite thing because I’m always like smiley face, I’m smiling when I say this—you have to use indicators textually in order to communicate what you would normally in person.

You often see this disconnect, or this split, you know, I’ve seen people, you sense something, a smiley face or making a joke, but you see the person when they’re sending it is emotionally, like not actually in any joyful mood—there’s that also, what is actually happening psychologically within you when you’re expressing in the digital.

It’s almost entirely interior. You’re almost just imagining the interaction you’re having, you’re not really having it. Which is basically what a digital interaction is. Also, that is a simulation, it’s not the entire thing, it’s the simulation of an interaction. It has amazing reach, and I will never argue that yes, being able to reach via communication beyond our physical has been amazingly enabling, but I don’t think one should replace the other by any means; and we need to design constructs where that doesn’t happen, and that engagement remains, where we’re not all isolated units talking to a device.

You’re trying to imagine breaking that down a little bit.

Yeah, and designing environments that allow that, and that are malleable, and allow that communication as well.