Fabrics & Foot Fetishes

But what moves her? Included here is a helpful, if abbreviated, list of Sarah Zapata’s interests, the foremost being—

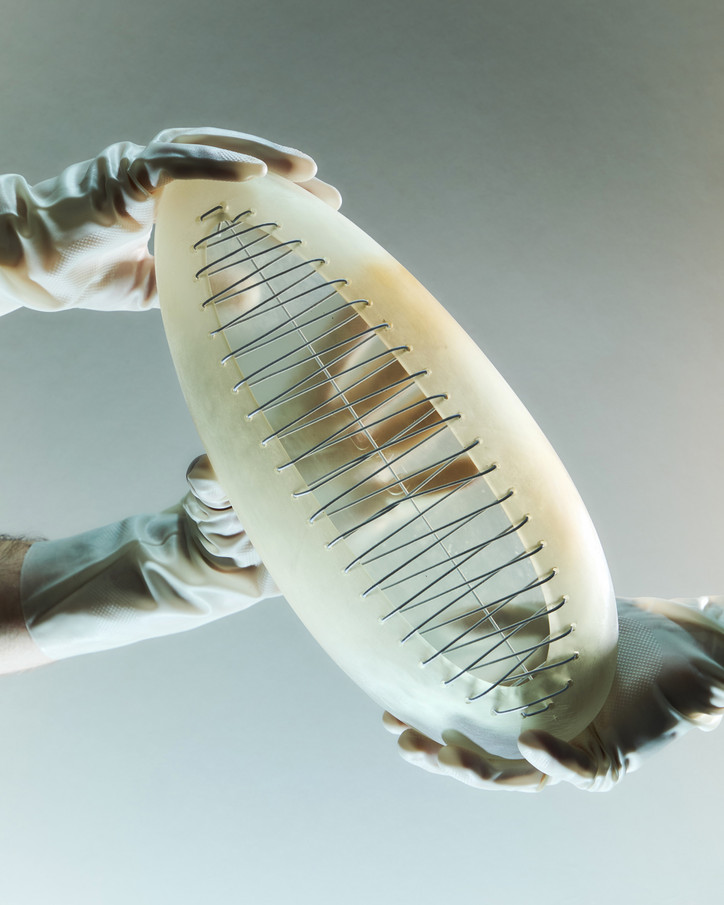

What’s more accessible than textiles? We’re in (almost literal) constant contact with cloth; tapestries and weavings have been traditional art forms for thousands of years. But one of Zapata’s strengths as an artist is her refusal to take anything for granted.

“I’m interested in the familiar,” Zapata says. “I think textiles are very familiar, and I’m warping that relationship.”

At her Performance Space show A Famine of Hearing, viewers walk into a square gallery room divided diagonally into two distinct sections, one red, one green. Walls of colored carpets stand in the center, perpendicular to each other, broken up by carpets hung on the walls referencing the style of stained glass windows. The red and green, she explains, expressed two questions on her mind at the time:

1. How did we come to accept modern Christmas colors?

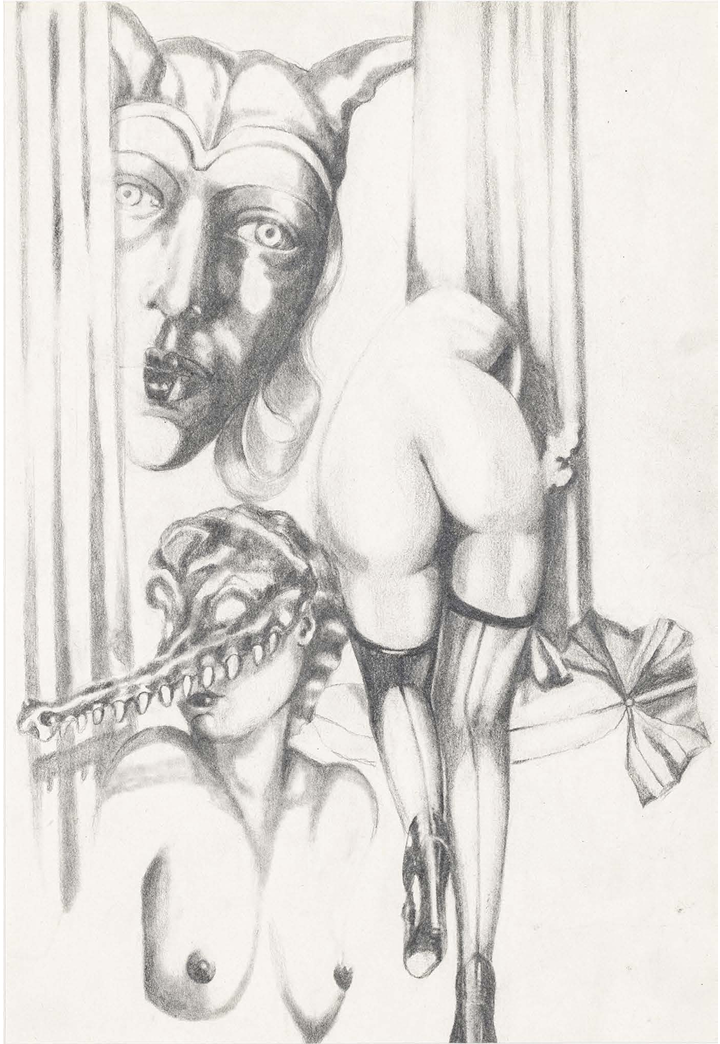

2. How could she work in her interest in the metallurgic trophy heads she came across while studying the Pre-Columbian Moche civilization?

Through research, Zapata found that a single Coca Cola advertisement had established green and red as a specific visual language for Christmas. “I liked these two colors representing something that has this sort of spiritual beginning and was then hijacked by capitalism,” sha said. As for the Moche heads, she explained, “I wanted them to be these agendered sort of figures from an anti-hero society, rather than the western canon.”

The result was a gallery space resembling a synthetic, fluffy Garden of Eden, or a trippy little cathedral. A high situation, if you will. In spite of its intricacies of intent, A Famine of Hearing is, at its core, about—

The art world is rightfully obsessed with access right now, and so is Zapata. We want paid internships and participatory museums! Better representation and more national arts endowments! And above all, when we see a carpet, we want to touch it.

Zapata knows this. “With textiles people are so hungry,” she says. “They just know that they can touch it, even if they’re not supposed to.” And in a gesture of humility, she often allows gallery-goers to feel her works.

All of her environmental installations are comprised of different components assembled specifically for the show; though each piece is for sale, Zapata is interested in giving an experience to the viewer that’s free and only exists once.

Zapata’s show If I Could, which ran at Deli Gallery in 2017, was a wall-to-wall exhibition of vivid patchwork carpet relieved by islands of stout, furry sculptures. Made in the aftermath of the 2016 election, to the tune of NPR playing while she wove, Zapata was amazed at how colorful and lush the installation turned out. “Everyone was in such a state of shock and needing to have some sort of comforting escape,” Zapata says. “ I think that I was definitely trying to give that to people, as well as myself.”

The title If I Could samples a song by Simon and Garfunkel, which in turn samples the Andean folk song “El Cóndor Pasa.” It’s the perfect name—a synthesis of Zapata’s Peruvian ancestry and—

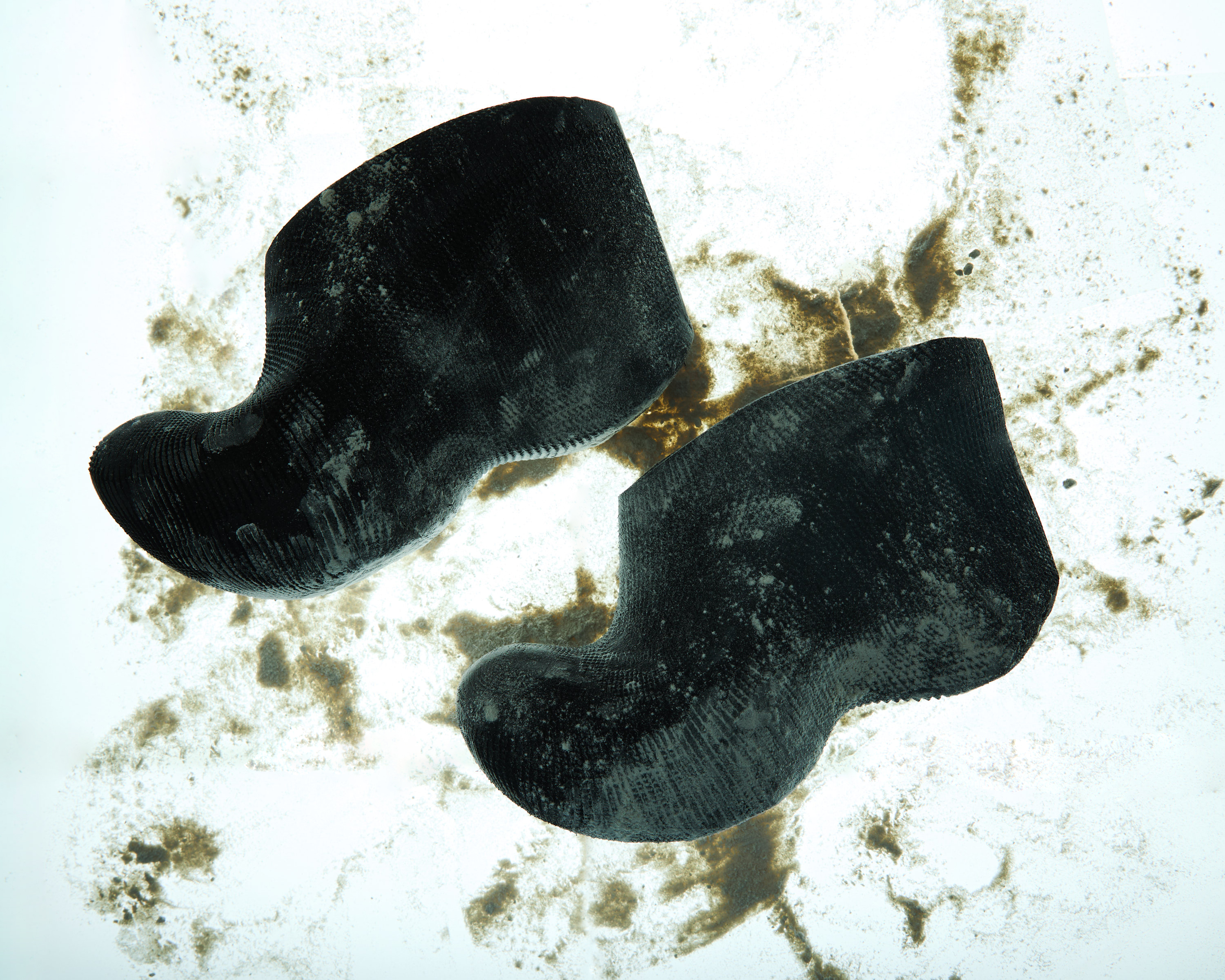

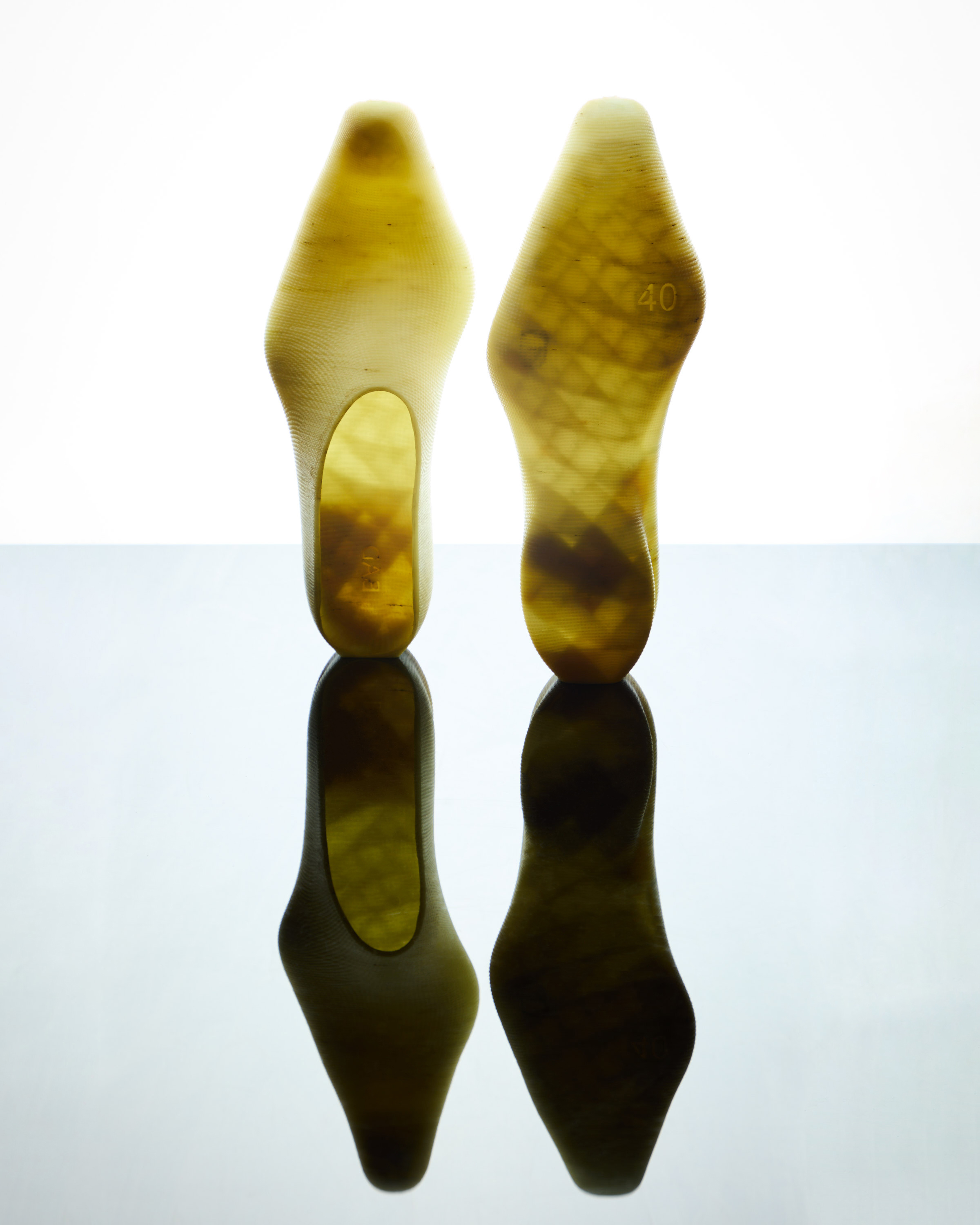

If I Could was installed in a way that made it nearly impossible for the viewer to take a good look at the work without taking off their shoes and plodding around the room, feeling the yards and yards of labor-intensive, carefully-constructed fabric on their toes. It was a scenario Zapata planned for and encouraged.

But what does humility have to do with textiles? Aren’t artists already supposedly eking out a humbling existence? (“Starving artist" trope anyone? Unheated studios?)

“Humility and guilt are definitely not synonymous,” Zapata says, “but those are the two pillars that I’m sort of living my life in.”

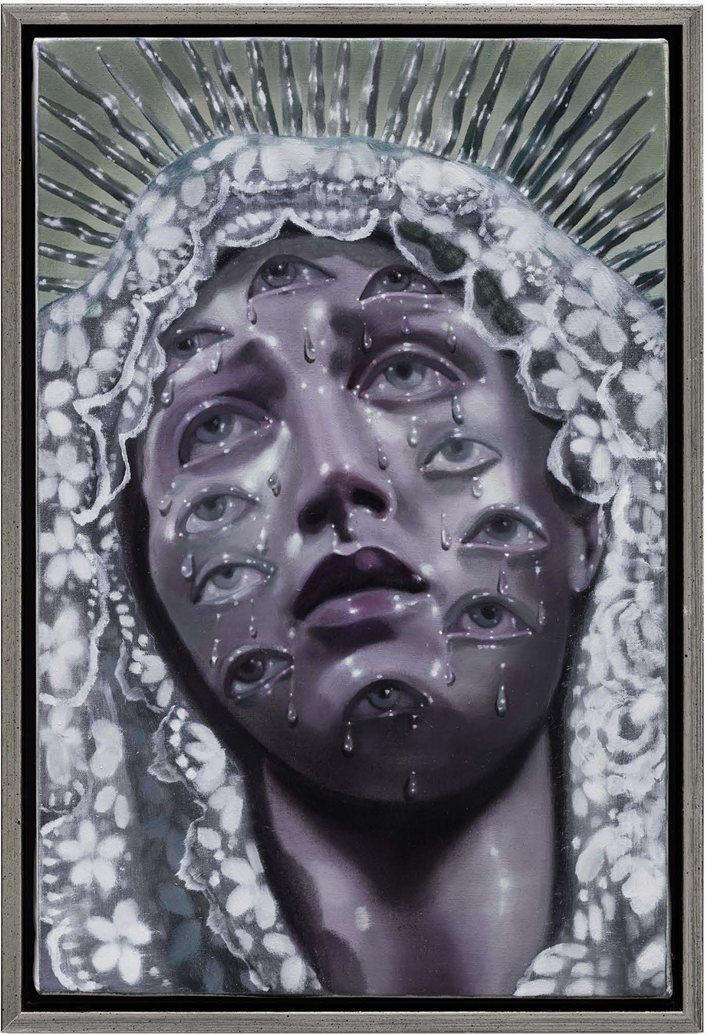

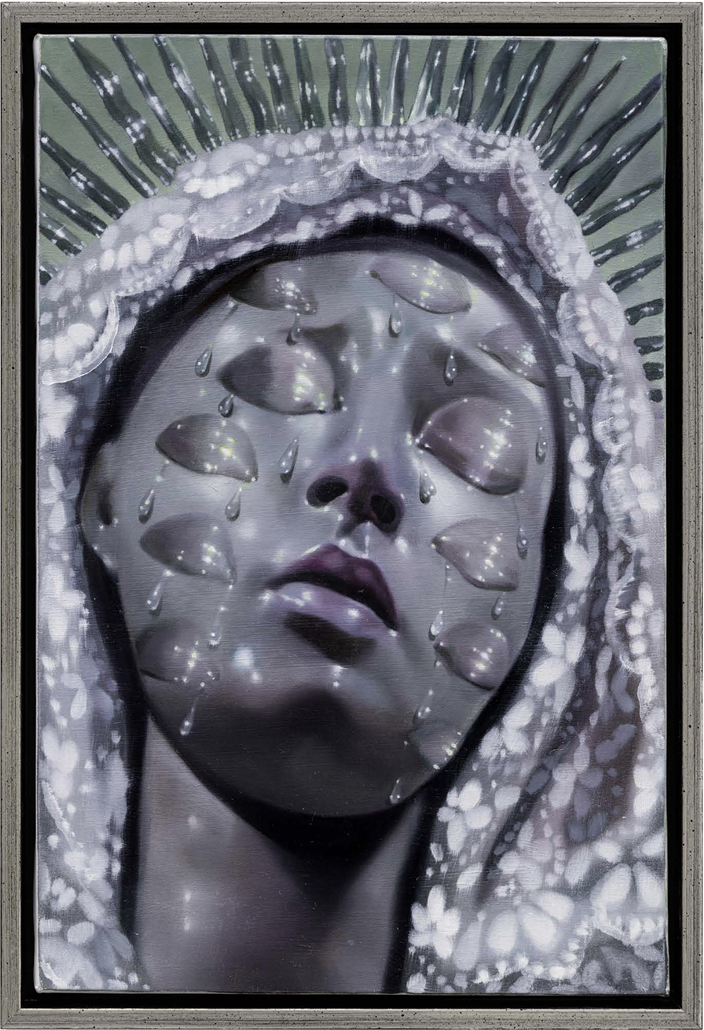

As a lesbian raised in north Texas and steeped, early on, in Christian evangelicalism, Zapata tends to deal with a lot of guilt. Throwing herself into theological studies is as much an act of healing as it is a manifestation of her interest in, as was the case with her questioning of Christmas colors—

Zapata began working in textiles out of a desire to form a tangible relationship to Peruvian culture, part of her heritage on her father’s side.

Since starting textile work at 18, Zapata’s spent a considerable amount of time in Peru, and has an upcoming show in Lima, for which she’s been researching rocks. “This is the first one that I’ve been researching around an object, but rocks are really important in the Bible, in the Battle of Jericho specifically.” From the research, she’ll write and then craft an idea of what she wants to produce in the form of watercolor sketches. Construction involves a lot of math, and the final product takes a lot of time.

Though the act of weaving is a solitary process, many of Zapata’s shows incorporate the works of other artists, including performances and readings. It’s a mode of humility, too: “But what was so great was that I was able to curate some performances that went on in the space, but they also took control of it, and it went out of my hands and was able to be activated in all these different ways. Which was great.”

Occasionally, performances will include readings of her own—

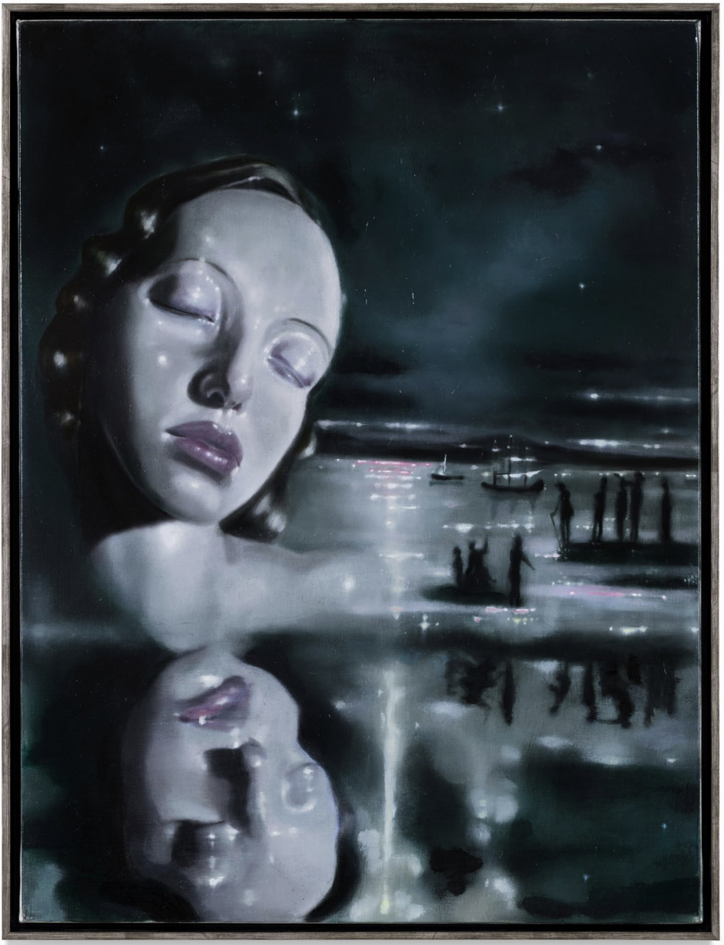

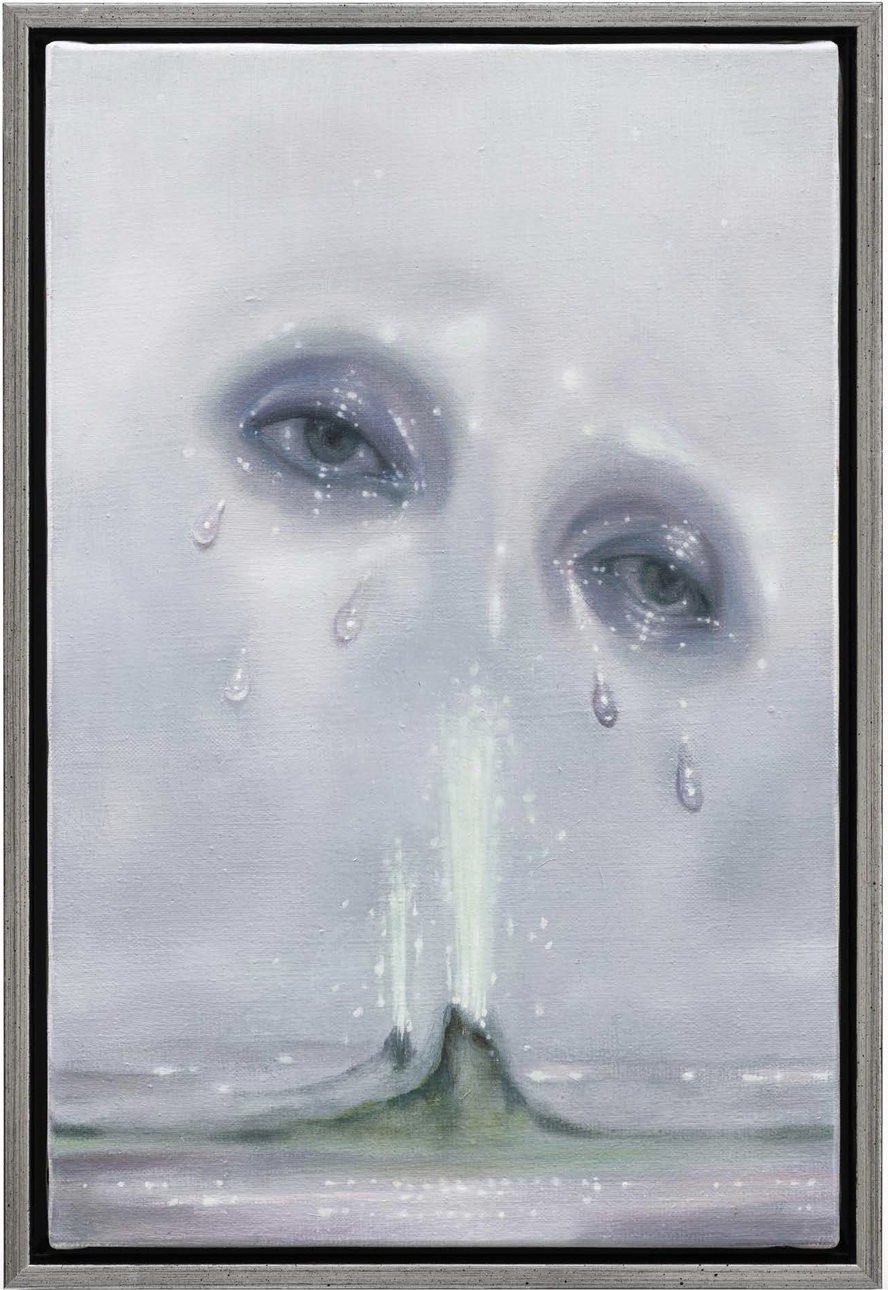

You could call Zapata’s foot erotica a sort of fanfiction. Biblical fanfiction, that is, injected with a particular strain of foot fetish.

The longest one she’s written concerns the canonical story of a woman having been healed of a 12 year period by touching the hem of Jesus’ cloth. In Zapata’s retelling, the cursed woman ends up in an affair.

“It’s just sort of everyday situations but using text from the bible to elevate it and change the situation,” she explains, half-blushing, half-deadly-serious. “The bible has really incredible, beautiful text. There’s something very satisfying about it.”

Religion, she muses, “feels like home, even if it’s not at all.” Regardless, it is inescapable. As is the connection between textiles and the feet, especially when viewers were encouraged to take off their shoes to fully experience If I Could. “Textiles are so related to the body, and I wanted to be in control of how they related to it,” she says.

The only thing that may be familiar to each of Zapata’s works is her tendency to warp any complacency—on a personal level or on the part of the viewer—into a sense of wonder. “I’m very comfortable with what I do but I’m always trying to challenge that," she says.

Her upcoming show in Lima revolves around the Battle of Jericho, rocks, and time. If her works are based on a question (such as why these Christmas colors?) this show takes a metaphysical cake: “I’m interested, now. in how we’re just dropped in the middle of time and having to navigate why things are the way they are. I’m interested in creating strange senses of time.” Until the next show, you can find Zapata weaving rock ruins, warping the familiar in her Red Hook studio.