Aubrey, Irreverence, and the Backs of People's Heads

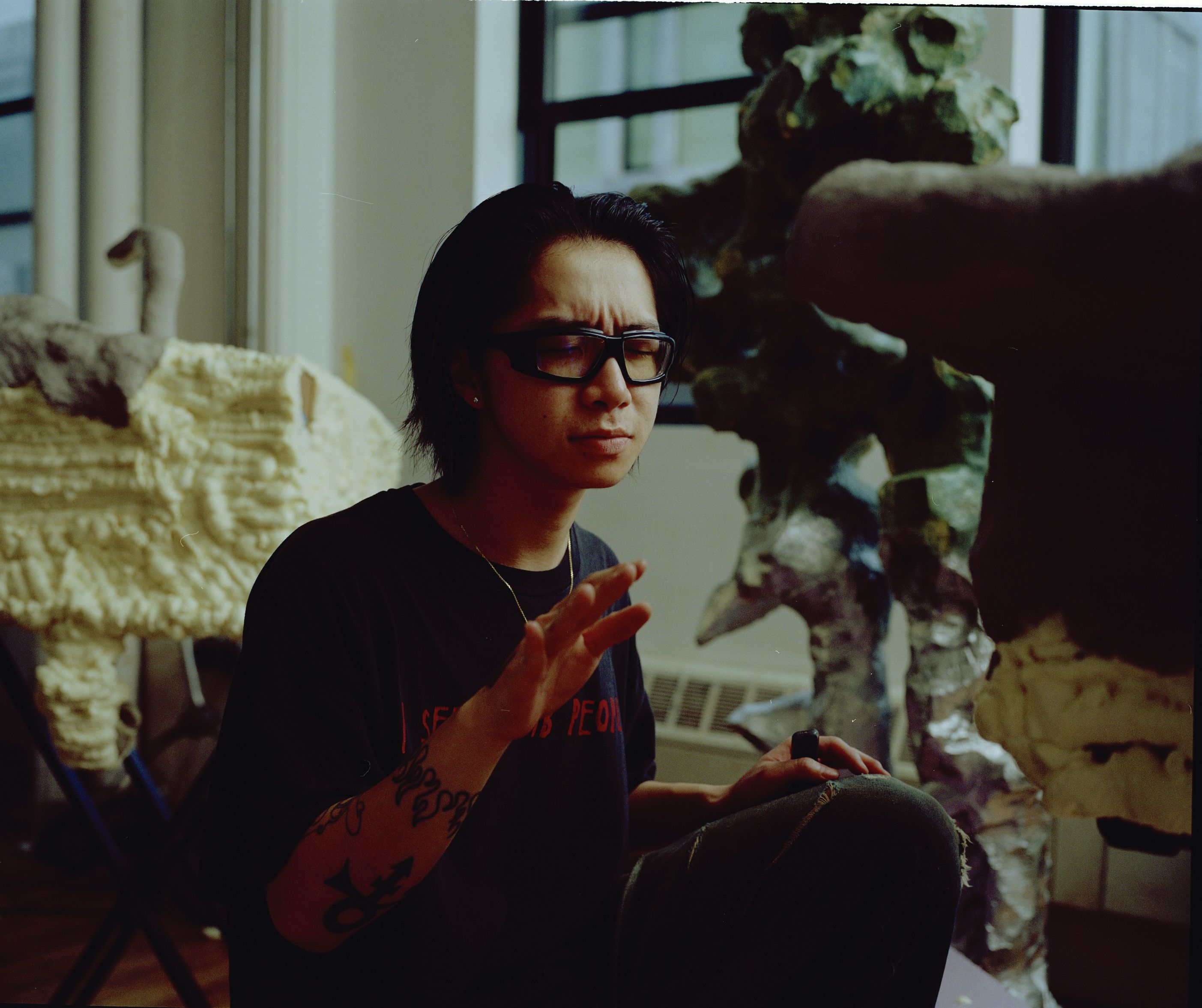

It’s a few minutes before 2 PM on a dreary Wednesday afternoon, and Osmosis, an eccentric Brooklyn sculptor-slash-Drizzy-enthusiast, is fresh off of his debut solo exhibition, PLEASE IT IS MAKING IT THANKS :). Hosted by Kapp Kapp, an independent Tribeca gallery run by brothers Sammy and Daniel Kapp, the show doubled as not only Osmosis’ first time being in a showcase entirely under his own name, but also his inaugural taste of a certain tangible latitude, marked by a noticeable brightening of the spotlight. Companion (Hachikō), a jarring cockroach-like sculpture that greeted gallery visitors as soon as they stepped out of the showroom’s elevator, was on the cover of the Brooklyn Rail, and strangers were recognizing him on the street.

He gives the cigarette butt a careless flick towards a line of parked cars on Jay Street, and leads us back inside the studio building’s elevator lobby. “Everything so much so, in regards to the work and the reference material, really comes from a place of irreverence,” he tells me when we get to his workroom. He’s wearing a black T-shirt that reads “I SEE DUMB PEOPLE” in red ink, faded dark-wash jeans, a thin gold chain with a small ying-yang pendant, and a pair of black boots flecked with golden lace-holes. We’re seated a foot or two across from one another in identical rolling chairs, and in the purple-tinted reflection of his larger-than-life square frames, the space’s expansive city-view windows are reduced to four zesty mini-rectangles. “There’s no material that is precious to me,” he continues. “Everything is fair game. And this extends itself to any accolades or accomplishments I may have, too.”

Two years ago, when I first met Osmosis, he was working out of his apartment, then doubling as a studio, on the edge of Brooklyn's Bath Beach neighborhood. His sculpting inventory shared a deep, cluttered garage with his father’s tools, and behind an upstairs door marked OFFICE, hordes of current and past projects seemed to fight tooth-and-nail with each other for breathing room within tight walls that felt like they were fastly closing in. In retrospect, many of the works that survived those humble beginnings wound up eventually seeing the light of day in grand fashion — a faux-bloodied T-shirt pointing a mocking finger towards nipple chafing, for instance, was most recently followed up by Runaway Bride, a wedding dress with two crimson streaks running down its chest, which went on display in a window outside of Theta this past April — but for all the impressive ground that has evidently been gained, Osmosis isn’t necessarily patting himself on the back. He puts art to me as just an “itch” he has to scratch: he’s more intent on not being bored than he is on having fun, and as much as his work may be playful, it’s just as much a dream occupation for its maker as a mode of survival.

As of right now, he’s been scratching the creative itch a bit more fervently in preparation for an upcoming solo show he has at Amanita, a gallery slated to open this fall in what used to be the fabled punk rock hotspot CBGB. Surrounding him in the studio, there’s a pair of staggering, awkward, DIY science project-evocative bathroom sinks stationed on identical keyboard stands, a Zombie T-shirt-wearing mannequin he isn’t entirely sure what to do with yet, whiteboards scrawled with obscure mantras (“2 CIGARETTES + THIS BROKEN HEART OF MINE”; “PURPLE”; “THE MINISTRY OF CRUELTY”), and a convoluted assemblage of hardware tools he assures me I can move out of the way to set down my tape recorder. The mischievous ethos of the room is somewhat visibly deadened by its weather-induced darkness, the same way that the works’ collective irreverent humor is afforded an extra weight by the rigid existential ultimatum that furnishes them. “Me being bored with my work — if that ever happens, just put a gun to my head and end me,” he says, blinklessly halting his fidgeting in the rolling chair. “Old Yeller my ass. Take me out to the back, draw up a fucking sunset, fake or real, I don’t care, and Old Yeller me.”

Born in Brooklyn to immigrant parents, Osmosis stumbled upon his now-fabled pen surname over a fateful series of events in middle school. He had loved the sound of “Osmosis” upon being introduced to it for the first time in a biology lesson, and when he came home to see Alton Brown of Good Eats hoisting it up on a whiteboard on television, he immediately changed his name on Facebook. “There’s a reason why I stuck with Louis Osmosis,” he tells me, of his decision to keep the name attached to his artistic identity. “Because it’s like, Oh, what the fuck? What the hell is this? Yo, what is that. Who the fuck do you think you are?”

Osmosis attended LaGuardia High School, the famed Upper West Side arts academy-qua-superstar-incubator, thanks to an intentional botch-job of the SHSAT (Specialized High Schools Admissions Test) he executed against his mother’s wishes. He earned a BFA from the Cooper Union in 2018, and though his dream as of right now is to become a professor — the only means of doing so being to either get an MFA, or make it big — he’s intent on the fact that you will never in a million years see him pursuing a Master of Fine Arts degree. “[People] get stuck in this rut, from adjunct position to adjunct position, and don’t have time to make the work,” he says, in a rationale he seems to have given thousands of times, about why he wouldn’t pursue teaching via the conventional route. (The spiel also includes the fact that he’d likely go into debt, which would be such a shame, because he would only have ever gone about it for financial stability to begin with.) “I really want to be able to teach on my terms.”

Osmosis often finds himself in situations where there’s an incentive to operate as a teacher of sorts, and although it’s a role he ultimately wants to play, as of late, the structural demands of it are something he’s beginning to grapple with. The current show his work is being featured in is “Lingua Franca,” a Kapp-curated group exhibition he’s described as “art Coachella.” It features a sculpture of his both aptly, and with a familiar tongue-in-cheek flair, titled Various Masses: a paper-mache mass, covered in inkjet prints of photos of crowds (or masses, if you will) pictured from the back, permeated at the top by the sort of long branch-garbage-bag contraption Spongebob would tote en route to skipping town. The object acts as a freestanding testament to its group-borne creative dilemma. “A couple of weeks ago, I really hit this fucking deep drudgery where I really hated the idea of being in crowds,” he says. “I just really hated the idea of gathering with people socially. Crowds just started looking like walls to me. For every crowd I saw, I just saw the backs of their heads.”

A concept he’s long been infatuated with as an antidote to the impasse is anonymity. He light-heartedly reveals to me that he imagines himself to have an alter-ego, named Lucas Mitosis, that helps him to make sense of himself in relation to others. But as much as it’s a gimmick as playful as most of his art, it’s also one that’s just as weighted — he knows that the only way for him to escape constantly having to announce his name is to make it big, and at that point, his name wouldn’t even belong to him anymore. “I wish I could, but I can’t,” he says, asked whether he’d push a button that guaranteed him complete inconspicuity. “The world in which we operate is so predicated on hyper-visibility. The gauge for success is when you walk into a room and people already know who you are. Everyone is their own publicist. Every post, every handshake — literally, just meeting people — you have to be like ‘Hey, what’s up, I’m Louis.’ And it’s fucked, because you ‘get lit,’ and then your name is public property.”

Which is, unfortunately for interviewers with anti-Drizzy predispositions, where Drake comes in. The spectacle of Louis Osmosis finding a way to segue into Drake in conversation lacks little in the brand of Oops, I did it again energy a clever fourth-grader would exude before geeking out about Star Wars conspiracy theories at the dinner table for the fourth time that week. “I’m about to go a mile a minute,” he tells me, barely suppressing a childlike grin, as his eyes light up behind his purple-tinted lenses. For Osmosis, listening to Drake’s Honestly, Nevermind was the most blissful he’d felt — even more so than his debut solo — in ages, because it doubled down on all the existential baggage he had been carrying, creative and personal alike, and threw it all back at him like a “weighted blanket, but one that was weighted with leeching lead.” Much of this baggage was rooted in these visibility-slash-invisibility interplays. “There’s a really long lineage of the club proper, as a site where one can take on a more libidinal position,” he explains, delving into the house music discourse Drake’s LP unsuspectingly ignited. “When you think of a club, everyone is facing the same way. If you’re on the dance floor, you’re only going to see the backs of heads, in a dark room — so it’s doubly anonymous. And everyone’s facing the same orientation. It’s giving zombies. And it’s this sweet fucking relief… it almost feels like fucking dying, man.”

He swivels a bit in his rolling chair, and scans the studio space. “Basically, with this next body of work, I kind of want to do what that album did.”

In a literal sense, he’s getting close. PLEASE IT IS MAKING THEM THANKS :) featured a whale vertebra manipulated into a booming subwoofer, blasting a persistently-droning recording of ambient-yet-challenging soundscapes easily fittable on a polarizing Kanye West release from five years in the future. But beyond strictly-sonic means, there’s also a certain catharsis — one Honestly, Nevermind made him experience in writhing torrents — that is, ever-so-increasingly, permeating his artistic approach just as much as the irreverence does. Early on in our conversation, one hand fiddling with a vape and the other theatrically gesticulating, he reveals to me with a breezy “you can put this in the interview” that his parents are divorcing. Growing up, though their relationship was strained, his mom and dad made it a point to remain together for the sake of raising their son in a “proper home.” In a light-hearted way typical of Osmosis, he jokes that most of the people he knew through adolescence came from a broken household of some sort, thus making this development the final “infinity stone” in making him fit in once and for all. Yet, also typical of Osmosis, behind the light-heartedness, there’s also the looming air of an existential burden. “The thing is, this is where the turmoil comes in, because now I’m a grown-ass motherfucker,” he says. “I’m involved in the divorce. This is, like, a three-party event. So that, I think, in a way has informed the space in which I’m making work right now. Insofar as before, I was — and still am — dealing with this really affected recoil. And now, not that it’s settled, but more so the doldrums have gotten even deeper.”

It’s one of several fragments of a reckoning Osmosis is actively doing with the demands of growing up, and at the same time that he does so, his work, too, is balancing the irreverent playfulness of youth with the burdened heft of incurred wisdom. PLEASE IT IS MAKING THEM THANKS :) was accompanied by an art book of the same title, wherein Osmosis hop-scotched masterfully between tongue-in-cheek imagery and purgative storytelling. One of the book’s more serious moments is marked by a firsthand narrative of his grandmother’s funeral. Handwritten, and featuring a scratched-out word every now and then, the story progresses numbly from encounters with Alzheimer’s disease, to grave misspellings, to mid-service family fights. “To substitute a shadow for a misnomer,” he concludes in its final lines, “is to be refunded our blunders, the specific blunders that remind me how happy accidents make me.”

As much as accidents make him happy, his studio practice, especially when vamped-up in preparation for a show, is markedly stringent. Last time I was here, it was mid-March, and as tourists and traffic droned from outside the window, he was frantically prepping for the aforementioned debut solo, slated at that point to open in a matter of weeks. Three months later, most of what gave the studio its chaotic energy then remains the same — two large whiteboards double as to-do lists and ink-scrawled manifestoes; provocative unfinished free-standing objects are dispersed like a wild-minded fourth-grader’s made-up avatars on the Mii Channel; tools are ubiquitous, hanging on walls, populating tables, sprawled out across the floor. The only difference, now, is that its mastermind is on to the next challenge: now that he’s gotten over the hump of his first solo exhibition, he has to make sense of what awaits him on the other end of newfound stature. And, in a way that’s simultaneously as inviting as child’s play, and threatening as life-or-death, the only way to prepare for whatever’s next is to do so in practice. “Everything is fair game,” he says, “so long as you know how to play the game.” When he tells me this, he’s talking about his nothing-is-sacred modus operandi, but at this stage of his career, it’s just as applicable to the winding road ahead.

One of Osmosis’ most sarcastic recent pieces is, perhaps, Shtick Figure (2022), a lofty assemblage of beaver-chewed wood pieced together into a Groot-looking humanoid by threaded rod, steel, epoxy, contact cement, and rubber. Midway through my first time meeting him, at his apartment, in 2020, he rose from the table we were seated at near his kitchen, and led me into the “OFFICE” room to show me the material. “I have a chewed piece of branch in the studio, that a beaver had chewed,” he said, moments before rising from his seat. “I’ve been sitting on it for a long time; I spent a year not knowing what to do with it. I’ll show you right now.” The demonstration came in response to a question I had asked about his relationship with nature as a muse — he had also, at that point, been actively waiting for a pigeon to excrete upon an in-progress sculpture sitting in his backyard before he could call it finished — and all in all, his response was that although nature wasn’t necessarily interesting to him, there just so happened to be interesting things within it. (Another one of the more jarring pieces in the “OFFICE” studio was a [humanely-sourced] tortoise shell, studded with remote-control car antennas that protruded from each of its scutes.)

In a grander sense, Osmosis’ approach to nature is in some way analogous to his ebbs and flows with life writ large. His entire characteral makeup, not just in art, is informed by a certain disillusioned aloofness, a removal from the equation that manifests itself in levels of flippancy so acute that they’re morbidly, viscerally, hilarious. “I’ve already accepted this zombification within me,” he says, “and I’m compelled by it. Which is on some art school subversion shit, maybe, but I don’t care. It’s like post-apathy; it’s like post-nihilism. Zombification is what animates me.” In conversation, and from a consumer’s standpoint, life seems to register for Osmosis as a joke that’s in the awkward stage where no one in the audience knows whether it’s okay to keep laughing or not, and for a few moments, there's a smattering of tentative, hesitant applause ringing from every other seat. Heavyweight cultural mainstays in similarly awkward post-limelight positions, like corporate co-optings of social justice campaigns, are frequent targets for him — another follow-up on his nipple-chafing tee series reads “THE FUTURE IS EMALE”; his PLEASE IT IS MAKING THEM THANKS :) art book features a short story in which the word “white” is cheekily censored in a way that makes it easily interchangeable with “whale.”

“It writhed and with each contortion let out an agonizing bellow,” the story reads. “The w***e’s speech was incoherent as if verbalizing an associative scrawl: ‘Al Gore… Gorky gore porn… I’m a ‘goraphobe!...’ ‘S-solar p-panel on the wall… w-who’s the d-doldrums of ‘em all?’”

The last time I saw Osmosis in person, he was sunken into a couch in the back area of Kapp Kapp, making small-talk with the gallery’s owners while people filtered in and out of the space to meet him and purchase his book. The books, spiral-bound and wrapped in plastic, were stationed in a fastly-shrinking stack on a nearby table, and as I flipped through the gallery’s sample copy, he joked with a painter who had come to the show with interest in buying one of his “Money Heart” pieces, which are comprised of bunched-up two dollar bills melded together to form heart shapes.

The “Money Heart” pieces are, if anything, perhaps the most trademarkable works in Osmosis’ oeuvre. He tells me that the mark of an artist that has given up is a regurgitation of their most successful formula. “It reminds me of Jordan brand re-retroing all of the old colorways,” he explains. “Because they don’t got shit. And they know that shit will fucking push.”

Whether he'll ever commercialize a work of his in similar fashion isn’t an answer we can have right now, because his take on quitting is just as nuanced as his philosophy at-large. “Sure it might be the artist’s fault to some degree," he says. "But I really get it. Giving up is kind of sick.”

* * *

“This is the most vibe-forward thing he’s ever done. And I think the impetus to do such a vibe-laden thing, with that being how it encounters the listener, points to the vacuousness of the landscape that we find ourselves in. Like, let’s meet the vacuum with another vacuum. Anything else you put into a vacuum, it’ll probably fucking die, because there’s no oxygen. A vacuum won’t. You know? This is vacuous music, and that’s a beautiful thing. Because it offers me — and maybe I’m getting a bit overly poetic here — but it offers me, the listener, the viewer, a moment in which I can kind of experience the vacuum without the threat of a material death. I can really come to terms with my own extremities in the two most visceral ways of being a human: which are dancing, and crying. There is nothing like music that you can dance to, and the lyrics are not only trying to be sad, but they’re so hollow in their depth that that makes it even sadder, too. It still hits, even though I know this was crafted to hit.” — Louis Osmosis on Honestly, Nevermind