Arava

How are you doing today? How's Paris?

Paris is great. I'm looking forward to the holidays. I'm gonna go to the south of France. I think I'm gonna do my summer dream south of France thing for the first time ever.

Oh my god, amazing. I've never been.

Yeah, me neither.

Well let's just jump right into it and talk about your film. I know that it's based on some personal aspects, but can you tell us a little bit more of what it's about?

Definitely. So, Arava is the story of two runaway teens in Jerusalem who are in and out of religious frameworks. They're searching for belonging, for identity, and for the true story between one another. They are two best friends and there is some romantic kind of love that is buried underneath their friendship. I think the story is also about discovering that.

I also know that you're from Jerusalem. Is Arava similar to what it was like for you growing up?

I grew up in Jerusalem in the early 2000s and for me, Jerusalem was a strange place to grow up because there's so many ideologies and so many different kinds of groups living away from each other. I left my home and school when I was 12 and I found the punk scene. At the time it was made up of people of all kinds of ages and backgrounds who were either facing homelessness or didn't want to return to their homes for many different reasons. Usually the reasons would be their ways of being didn't really fit ideologies at home. Communities that didn't accept them. You always see those kids when you grew up in Jerusalem. I was 12 when I first approached a group of kids that were a little bit older than me and I didn't really have a space in my own community I felt at the time. I found myself within a couple of months just hanging out in that scene and living in the squads, hitchhiking, and stuff. And it stayed that way for a couple of years.

Wow, you did that at 12?

Yeah, 12, I guess 13 was when I officially left home. It was interesting too because I came from an Orthodox family, but I didn't leave because the Orthodox background was pushing me out. It was actually kind of the opposite. My family specifically and the specific Orthodox dynasty that I’m a part of, are very accepting and they were always like, "You can come back with a mohawk and tattoos." But at the same time, my living environment and my family had a lot going on and I left that community. The film touches on that journey of a young person trying to find out more about the relationship between religion and faith.

So this movie is sort of a sneak peek glimpse into what it was actually like for you.

It was my personal story, but also a bit of the mosaic of punk culture. It was a big thing in the '90s and the early 2000s for us. Now it's kind of gone.

What was it like?

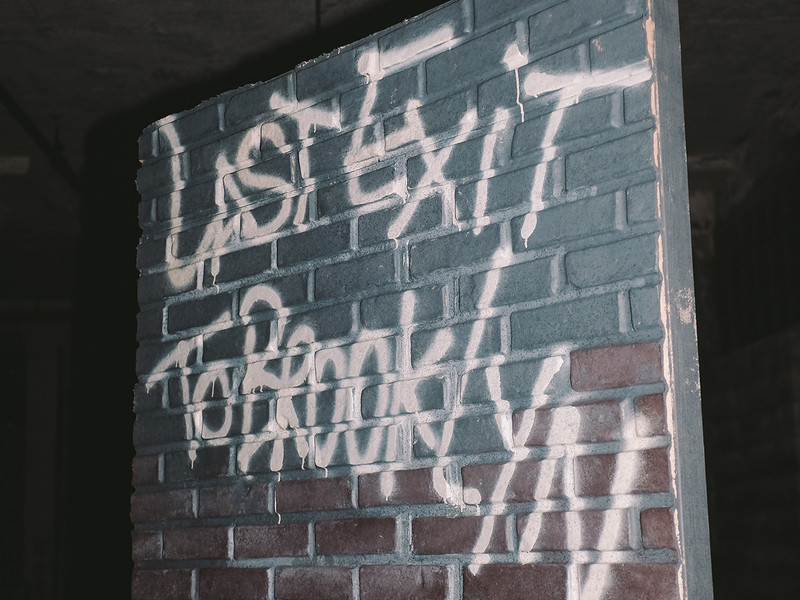

It was mostly punk music in Hebrew and Arabic. Everything was very improvised, very DIY. Sometimes there were not even real instruments, but it was hundreds of kids from really different backgrounds that would get together in abandoned buildings. They would throw these crazy raves. People were living in the squads and your whole life revolved around it — nothing else that mattered. No one was really going to school or were part of mainstream society in any way.

That's so interesting. It obviously must have been difficult for you to do that, but you had that community around you.

My mom who passed away unfortunately, suffered from a lot of mental illness and untreated trauma. Back in the day, where I came from, there was zero knowledge and access to mental health resources and ways to help. So I didn't really know how to deal with my mom's sickness and I didn't really think that I was helping. There were times that I was at home when she needed me more, but when I felt like I was not really needed in terms of being a caretaker, I spent the rest of my time with this crowd that was like my newfound family.

When I wrote the film I was trying to look at every character in the story and every person that I've encountered in my real life without judgment. Tell things for how they felt, and not how they actually were. I'm focusing more on the feeling.

I feel like that's a good distinction to make, the actuality of something versus the feeling behind it. Even if the feeling behind something isn't what actually happens, sometimes that has more power over you and how you perceive things.

It's so true. Somebody who read my feature was like, "Well, you're dealing with teen homelessness and you're dealing with youth at risk which are not really light topics." But I'm dealing with them in some sort of way that feels, not very tear-jerking, you know? Cinematically speaking, I thought about this a lot and I came back to that person and I said that I'm trying to convey the feeling of a teenager in that world rather than an adult looking at these teenagers with a judgmental eye.

A lot of the times when people deal with things like youth at risk, the topic is depicted focusing on misery. Those years were definitely some of the most challenging years of my life, but also some of the best. So much of the DNA of who I am as an artist is embedded in those years. So for me to just look at all of it as dangerous and bad would not be doing justice.

One hundred percent. Just from the mind of a teenager, once you're in it that's your world. You aren't looking at it from an adult perspective like, "Oh, this is dangerous. Maybe I shouldn't be doing this." When you're young you think you're on top of the world and nothing can hurt you.

When you're a teenager, I think so many of these things come together. The saddest you've ever felt or the most on top of the world you've ever felt can both exist in one day. I think that you're learning the scope of your own emotional landscape. It was really important for me to not lose those nuances looking back at these stories as an adult. I'm very lucky cuz I have a lot of journals that I wrote when I was a kid.

You brought up earlier that a lot of the music when you were growing up in that scene was DIY, maybe people didn't even have instruments. Maybe this is just a dumb question, but were those songs ever produced?

Some of them, there's a few. There are a couple that made it to the internet. But so many things are just gone and they're gone forever. It became an obsession actually when I started writing the feature. I was contacting everyone I could from the past. I’d be like, "Okay, do you have any photos, burned CDs with like erased sharpie writings that you don't know what it is and it just sits there? Just give me everything."

I went back to Jerusalem after not living there for about eight years at that point. I rented a tiny little room in some apartment downtown and I told people to bring things there. Bring anything like CDs, clothes, and anything you don't want.

So this was all inclusive of the years of research that it took for you to make Arava?

Yeah, it was a part of that. People shared really personal things with me, but they never even asked to have it back. Some of them I still have and I'll have forever.

That must have been cathartic for you to revisit your past and look back on what you went through, but looking at it from the perspective that you have now.

Something that was happening to me a lot before I made the film is that my memory just kind of erased a lot of years because they were traumatic. And I left when I was too young to leave, obviously. I think I just didn't wanna look back or think about it. I was like, "Okay, I'm moving to another country alone and I'm gonna just... fuck it, see what happens and never look back."

It was really traumatic when I lost my mom. Then when I made the film, I think it was also a process of healing. It was time to piece together these really blurred images to try to understand what happened there. I think that in this whole research in the film and in me contacting all these people from the past, it was all part of some sort of self-portrait.

You do casting and have your own casting agency, so how was the casting for your film?

It was the best part and the part that when we premiered the film that people were the most excited about it. There's two leads, Batel and Swell. It's funny cuz Batel was actually a casting assistant for Memorial Di in New York when I first started working on film scoutings. She was an assistant and was the best scout. She has a really good eye for characters and she has really good taste, really good references. I was so impressed, like a kid this young, with this crazy world of references. I'm not even gonna have her world of references in 10 years, you know?

Wow.

So she was working with me and then simultaneously I scouted Swell on the bus near Jerusalem when she was 18. And I was like, "Hey, I might make a film one day. I like you, you have something— can we keep in contact?" And she was like, "Yeah, sure." In the meantime, between meeting Swell and making the film, Covid happened and I told Batel, "Hey, I don't know if the world is ending or not, but if it is, we have to go back to Jerusalem, and we have to make something about Jerusalem."

So it all starts from actors. Then we saw Swell at an audition. I was like, "I met this girl a few years ago, let's call her in." And she came for an audition. They became friends and they actually became roommates for that summer.

Working with people that already have that connection is great because as good as actors are, I feel like unless it's something in real life that they're tapping into, it's kind of hard to portray those emotions.

I completely agree. For us too, we do so many non-actor, non-model kind of things. It's a lot easier for us to approach people who are similar to the characters in real life in some way. They have something in common with the characters. Having these two girls from Jerusalem who have this friendship already and this dynamic. The dialogues are mostly improvised. We needed them to bring a lot of their own spirit into it.

In your director's note you drew comparisons between religion versus faith, individuality versus collective identity and then the battle between fantasy and reality. I want to dive further into these comparisons, especially in how they relate to your film.

Yeah, I would love to. In the first part we talked about religion as a framework and then faith as something that is more metaphysical. I think that especially for Judaism, there's a lot of conversation in the non reform worlds– in the religious worlds of how much should the practice change according to an individual, according to the times, or according to certain conditions. This debate and this discourse is always alive.

For example, in America, if you see someone having tattoos and wearing shorts, they could be super Christian, but you wouldn’t know. In Judaism there's a lot of things around modesty. So asking yourself where you can challenge things and the process of leaving the community, but not as a rebellious thing, more as an individual search thing. Where does it meet you inside and where does it meet you outside?

One of the characters, Arava, she's quiet and she says out loud, "I don't believe in this shit anymore. It's not with me anymore. I don't care." She has done some bad stuff and, and then there's the other girl who is always talking about God, but she's the one doing things that are quote unquote questionable. She's the one that wants to go, pray, and go through this process of redemption, but the other one ends up doing it instead. It's kind of how practice and belief are sometimes really far away from each other.

That's so interesting. There's a lot of different pieces of cinema written and revolved around the Jewish community, especially in New York. So it's super interesting to hear from you and your perspective on it. Maybe not just showing the modesty, rules, or the things that are for people who aren't Jewish.

I love that you said that, because sometimes I'm like, does what I try to do actually communicate? What you said is so reassuring because that was one of my biggest challenges. When I see all these films that showed in Cannes, that were kind of anti-orthodox, or films that talk about oppression of women in the orthodox community. It's shocking.

For shock value.

Exactly. Filmmakers kind of unfortunately fall into knowing that, okay, if I make a film about an oppressed woman in the orthodox community, people are gonna click, people are gonna wanna see it. I don't see my own representation in anything actually. When we were kids, we were punk fucks, but we looked like teenagers everywhere. But because it happens in Jerusalem, it has an extra thing to it that I think is interesting.

I find these topics so interesting where someone is brought up to believe certain things and then develops that intrinsic feeling inside to question that, which I feel takes a lot of strength and bravery. Going against what you already know, especially in communities where you're so conditioned to believe that things are one way.

We all have taboos in our society in different ways. Once you're not a part of mainstream society, you are probably more likely to question certain things. That's the case with the characters in my film.

What message do you want your audience to take away after watching your movie?

I always have a different feeling when I think about that. Every day it's something else, but I guess today I would say that I really would love the audience to not look at the characters in a judgmental way. And on the same note, to not look at people in such a judgmental way, in a polarizing way. I would love to bring a little bit more nuance back to the way we look at people and their worlds.