The Guggenheim at the Edge of Visibility

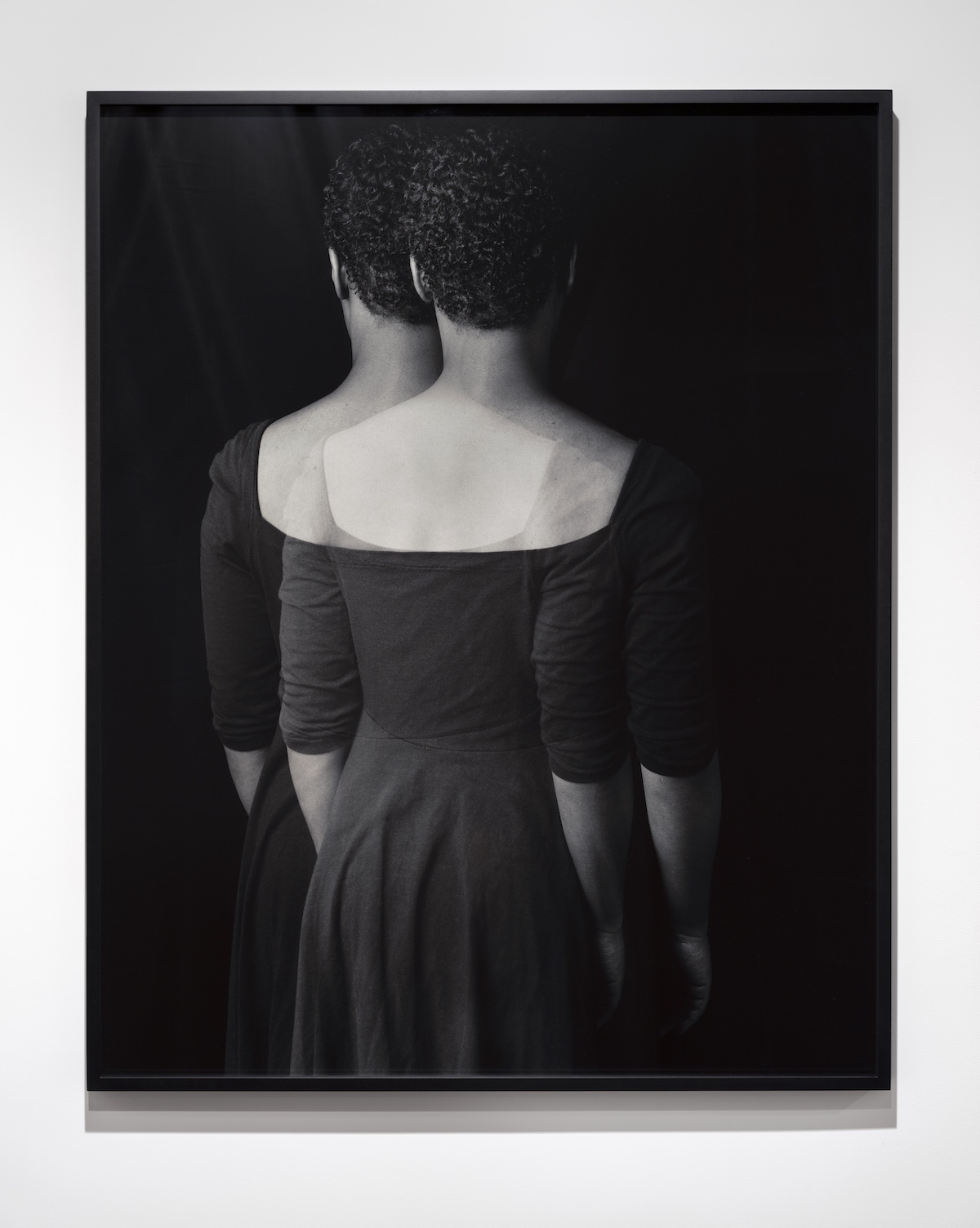

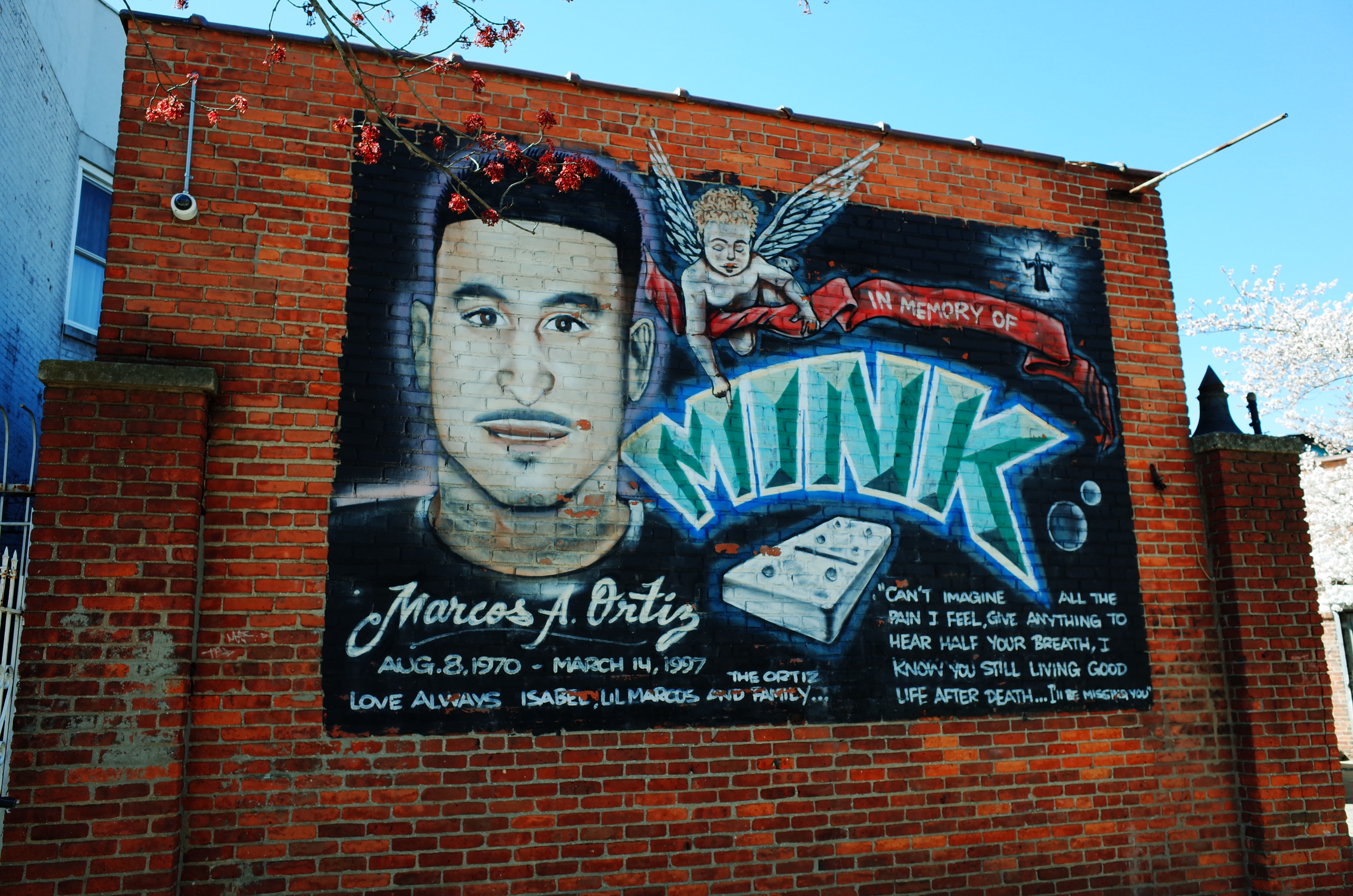

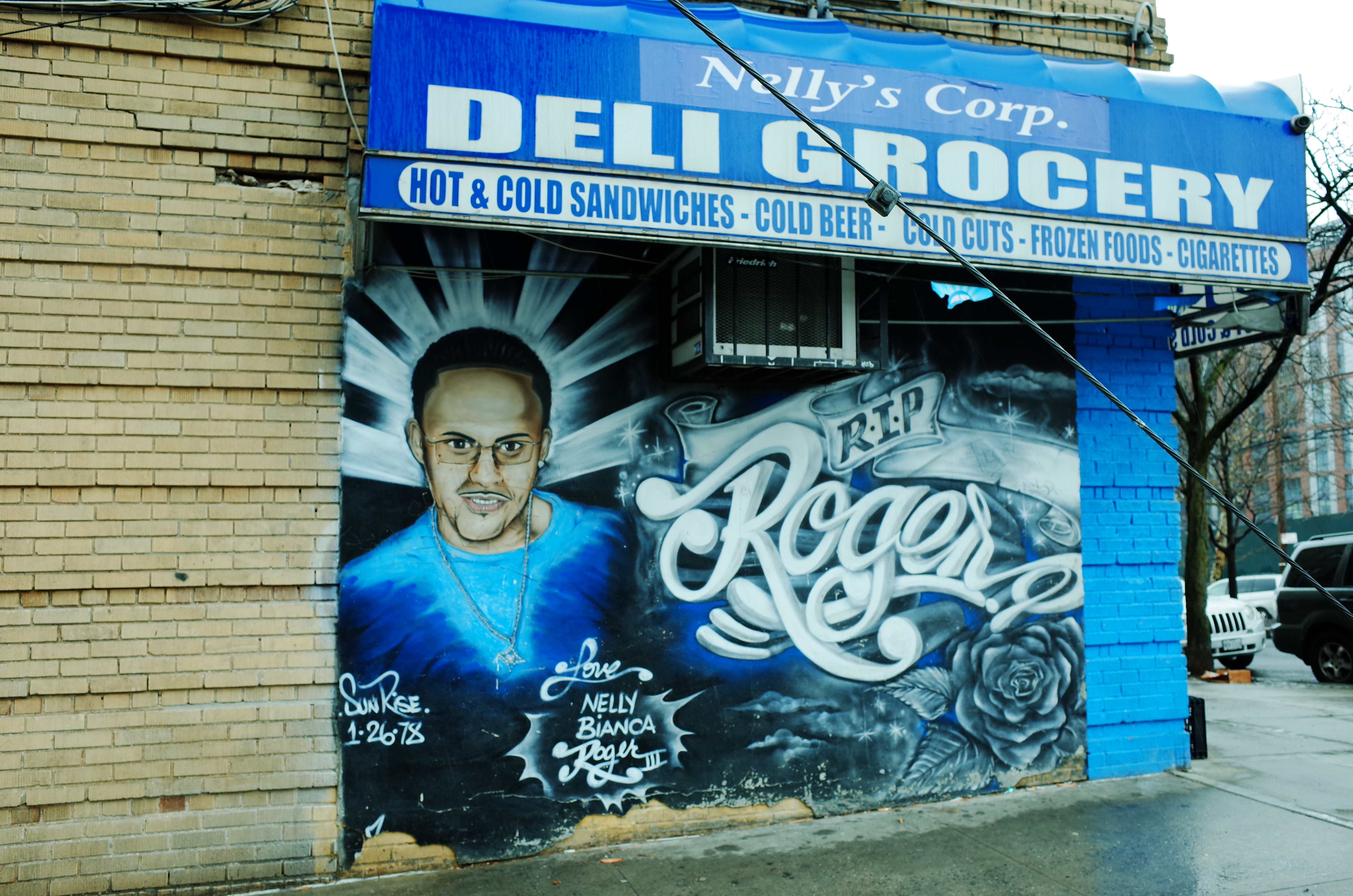

A long lineage of Black artists that have engaged the “edge of visibility” make up the ideological ancestry of Going Dark. “The traditional esthetic of black art, often considered pragmatic, uncluttered and direct, really hinges on secrecy and disguise,” Guyanese-American painter Frank Bowling wrote in his 1971 essay “It’s Not Enough to Say ‘Black is Beautiful.’” “The understanding is there, but the overwhelming drive is to make it complicated, hidden, acute.” In the following decade, artist Lorna Simpson would turn on Bowling’s secretive hinges – a 180 degree turn, to be precise — utilizing the compositional device of the Rückenfigur to deny the viewer’s gaze by turning her subjects away from the camera. “I am invisible,” says the unnamed narrator in Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man, “simply because you refuse to see me.” For Simpson, however, the power of her images lay in reclaiming the power of that refusal for the subject. The elusive eponymous figures of Faith Ringgold’s paintings Black Light Series #3: Invisible Man #1 (1968) and Black Light Series #3: Invisible Woman #1 (1968) also derive their (in)visibility from a refusal to be fully seen, as do the figures in Kerry James Marshall’s paintings Invisible Man (1986) and Two Invisible Men (1985). In her Invisible Man Series (1988-1991), which documents the residents of a Harlem neighborhood, Ming Smith withholds the identities of her subjects by intentionally producing blurred and low-light images — refusing to deprive them of their anonymity.

For some of the younger artists in the show, going dark is a strategy to evade the pernicious shadow of surveillance and overexposure in the digital age. Some artists in the exhibition go dark by literally darkening their images and paintings, using pigmentation, monochrome, opacity, or lighting techniques; others modulate their (in)visibility through material selections and print methods; still others go dark by way of technological interventions like chroma-key greenscreen/bluescreen and Photoshop.

Since James began her tenure at the Guggenheim in 2019, the (art) world has seen a drastic upheaval in how it navigates issues around race, reaching a fever pitch in 2020 after the killing of George Floyd. That turbulent “reckoning,” as many have called it, has seen an equally inelegant decrescendo in the years since. It is difficult to engage with the questions posed by Going Dark without calling to mind the art world’s habit of tokenizing Black curators; when David Zwirner hired curator Ebony L. Haynes to head a new gallery at 52 Walker in 2020, the opening line from the New York Times announcement of her position referred to her merely as “a gallerist who is Black”; the Times article announcing Dr. James’ own appointment in 2019 opened with, “At a time when museums all over the country are trying to increase the number of people of color on its staff, boards and walls, the Guggenheim Museum has hired its first full-time black curator: Ashley James.” Going Dark’s engagement with the precarity of representation feels especially timely, arriving at a moment when the diluted mainstream agenda of identity politics seems to be collapsing in on its shallow foundations.

But that timeliness wasn’t on James’s mind as she assembled the exhibition. “I never like to think about my exhibitions as responding to the cultural moment,” says James, who earned her PhD from Yale in African American Studies and English Literature. “Black studies has always had a really skeptical and complicated relationship to representation — the question of representation is endemic to my field.” As for her own place in that relationship: “I wouldn’t say it was an autobiographical working-out of a question, but in the same way that I say that representation is just a critical discourse of the 21st century, it's not a surprise that I would then be implicated in that too,” James says, sounding somewhat surprised that I made the connection. “I'm certainly aware of what my position vis-a-vis the museum is in terms of my blackness,” she concedes. “And that I'm the one going dark, or forcing the museum to go dark, and ushering the Black people into this white space.”

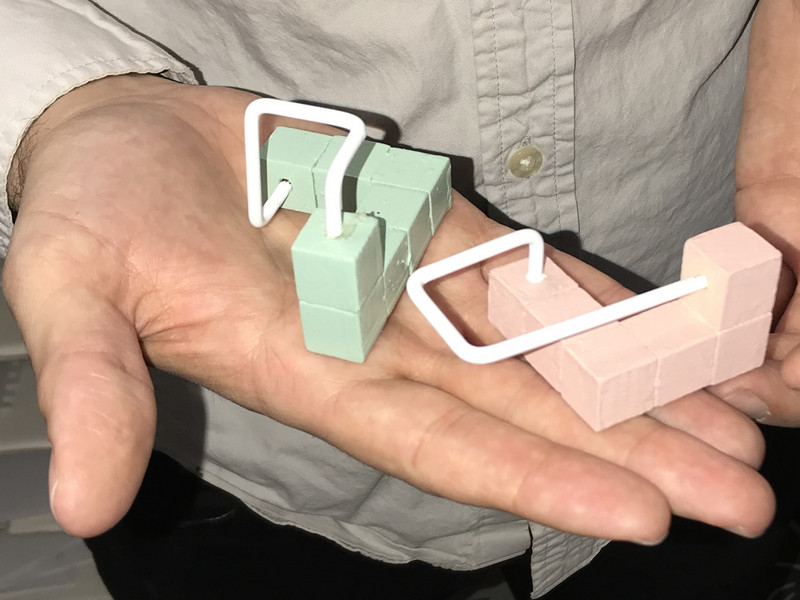

While Going Dark marks James’ second exhibition at the Guggenheim, it’s her first in the rotunda. She worked on the exhibition and catalogue for about a year and a half after settling on its concept. Between spring of 2022 and the opening of the exhibit in October 2023, James spent a lot of time with replica models of the familiar white spiraling ramps and clandestine bays of the rotunda. Filling a space of that scale presents a unique challenge for a curator, but such a distinctive venue can also engender new ideas. It was in a meeting over one of those replica models that American Artist and Dr. James came to a realization that birthed the former’s site-specific installation Surveillance Theater (2023): the Guggenheim resembles philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s late-eighteenth-century concept of the panopticon. “As a correlation, I think it's a little on the nose, but at the same time a lot of people don't necessarily think about that,” says American Artist. “The only thing that's missing is this central tower.” In place of that tower, they created a conspicuous globe that hangs from the oculus above the rotunda, recording visitors through 360-degree CCTV cameras. From the camera’s view, everyone in the rotunda is visible — for better or worse.

“Knowing the scale and significance of this institution, I wanted to do something that I felt would play with the uniqueness of what that opportunity allowed,” American Artist explains. “I was thinking of people visiting as a component in the work — the average Guggenheim Museum-goer, what are they expecting? What if I show the way that this museum and all museums are implicated in this relationship with the courthouse, the university, the jail, the factory, the airport — all of these things have similarities, especially bureaucratically and economically — the way that even beyond my piece, you have to go through security to get in the building. I wanted to do something that feels like it's everywhere, and I think the surveillance aspect played into that.” Behind a curtain in one of the rotunda’s bays are several 4K monitors that display a live feed from the camera, equipped with an AI software that matter-of-factly and somewhat touchingly identifies each moving visitor with the onscreen label of “human.” But in order to enter and view the live feed, visitors must first relinquish their phones and place them in small locked pouches provided by an attendant. To have the pouches unlocked, they must return to the ground floor of the museum. According to American Artist, the idea of temporarily dispossessing visitors of their phones preceded the rest of Security Theater.

“I think of it as a sort of trade-off for this abundance of visuality,” they describe. “That room as an offering was an attempt to seduce people into being willing to give over their phone, and then partake in that experience of not having their phone. Most people think it's the other way around, but the room is actually there to get you to give your phone away.” Those who continue after Security Theater, instead of immediately descending to unlock the phone pouch as I saw several visitors do, experience the remainder of the exhibit disconnected to the digital realm. In my own visit to Going Dark, I was immediately struck by how naked I felt without access to my notes app or my camera — and powerless to access my own tool of surveillance and documentation.

Tiona Nekkia McClodden’s series of paintings Very, Very Slightly (2023) also seduce the viewer into participating in the work, in this instance with prayer benches placed in front of the paintings atop a plush red carpet. The paintings depict advertisements for Black femme mistresses pulled from 1960s and 70s BDSM magazines and are printed on leather, a material that appears often in McClodden’s work. The figures of these women are rendered in black, blue, and red dyes and the diamond dust that gives the paintings their name: a type of diamond known as “very very slightly” or VVS for its subtle flaws that create a distinctive sparkle. The women in the paintings are elusive to the eye and — as I learned when I submitted to the prayer benches — most visible when one kneels before them.

“Especially with the red carpet, I'm definitely thinking about churches, specifically Catholic churches, and spaces of piety and prayer. But there's this other aspect of trying to figure out how to tease at people's desire,” McClodden says. “The best view is on your knees, and that's just it. I had to get on my knees repeatedly to make this work, so I'm transferring something that I enacted for myself.” Very, very slightly diamonds or VVSs are popular references in music, particularly in hip hop — I personally think of the VVS cufflinks promised by Beyoncé to her lover in the “Upgrade U” outro. “I am a child of hip hop, and I was born and raised in the south. I heard it but I had no idea what VVS meant. I was too poor to. And then I got to a certain age and I found out. The idea that the diamond that Black people like the most is beloved because of its sparkle and its imperfection and its shine: I was like, oh God, how beautiful and poetic,” McClodden explains. “And then thinking about leather and the idea of employing it… leather is fine over time, but it still has to shine. “Very, very slightly” is literally how I have to deal with the leather. I can't be abusive to it, otherwise it rejects the work that I'm trying to give it. I thought that it would be something very beautiful to bring my cultural relationship to the diamond and blackness, and think about these Black women as these kinds of diamonds, and figure them as such.”

Very, Very Slightly addresses the connection between the erotic and the unseen more directly than any other work in Going Dark. As both a member of the BDSM community and a contemporary artist with aversions to hypervisibility, McClodden has spent a lot of time thinking about the kinds of pleasures that can only be sustained away from view. “I like to play in the areas of distance,” she says. “I'm not exactly interested in going there all the way — I like not consuming something because it makes me still have a desire for it. In this time where I think there is a desire for the audience to consume everything, to consume ideas, to consume the Black figure in a certain way, I have to have some obscurity to also allow distance and sustain my own desire for my own work.” Her unwillingness to offer herself up to that kind of consumption in tandem with her work is part of why McClodden chooses to live in Philadelphia, where she feels she can maintain a greater anonymity. “Visibility as someone who often tries to hide is really something I'm always dealing with trying to negotiate. Currently I’m at this point in my career where I'm reclaiming a particular space and visibility of how I want to be seen, how I want my work to be seen.”

American Artist echoes a similar apprehension of the visibility that accompanies their practice and career. “The further I get into my work, I want you to just spend more time with the thing I'm trying to say, and I feel like it's going to happen less and less.” When I ask what makes them feel the most exposed, their reply surprises me. “This show. I think the visibility of this show in our professional sense is really next level,” says American Artist. “The idea that anyone could come up and see this thing that is very close to me and has been close to me for a long time does feel sort of exposing.”

To close our conversation in the Guggenheim’s reading room, I ask the two artists which would frighten them more: to be seen always and completely, or never at all?

“To be seen always and completely,” McClodden answers. “I've spent the majority of my life being overlooked, even in the more intimate spaces of family and everything. I was such a quiet kid. I distinctly remember thinking I could be invisible or something. And as much as that could be a painful thing, it actually is immense relief right now, which is what I like. As soon as I get back into Philly, I'm invisible.”

“To be seen never at all is more frightening to me,” American Artist says swiftly and decisively.

As I thank the two artists for our conversation and gather my belongings, I think of the words of Fred Moten: “I believe in the world and want to be in it. I want to be in it all the way to the end of it because I believe in another world and I want to be in that.” As I emerge from the museum, I mentally prepare myself to be in the world again — to believe in it, to relent to its gaze. I prepare to be seen.

"Going Dark: The Contemporary Figure at the Edge of Visibility" is on view at the Guggenheim from October 20, 2023 until April 7, 2024.