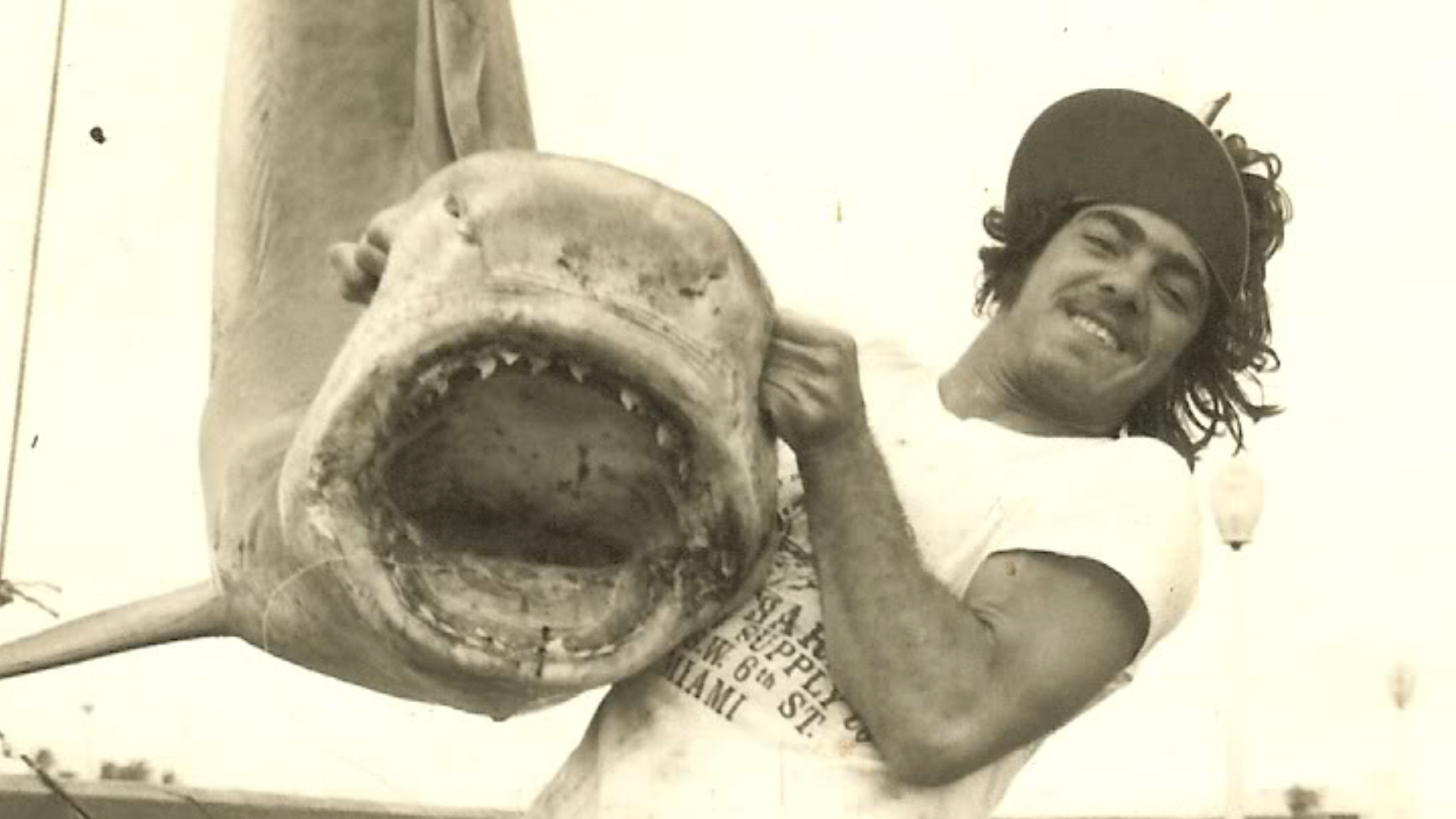

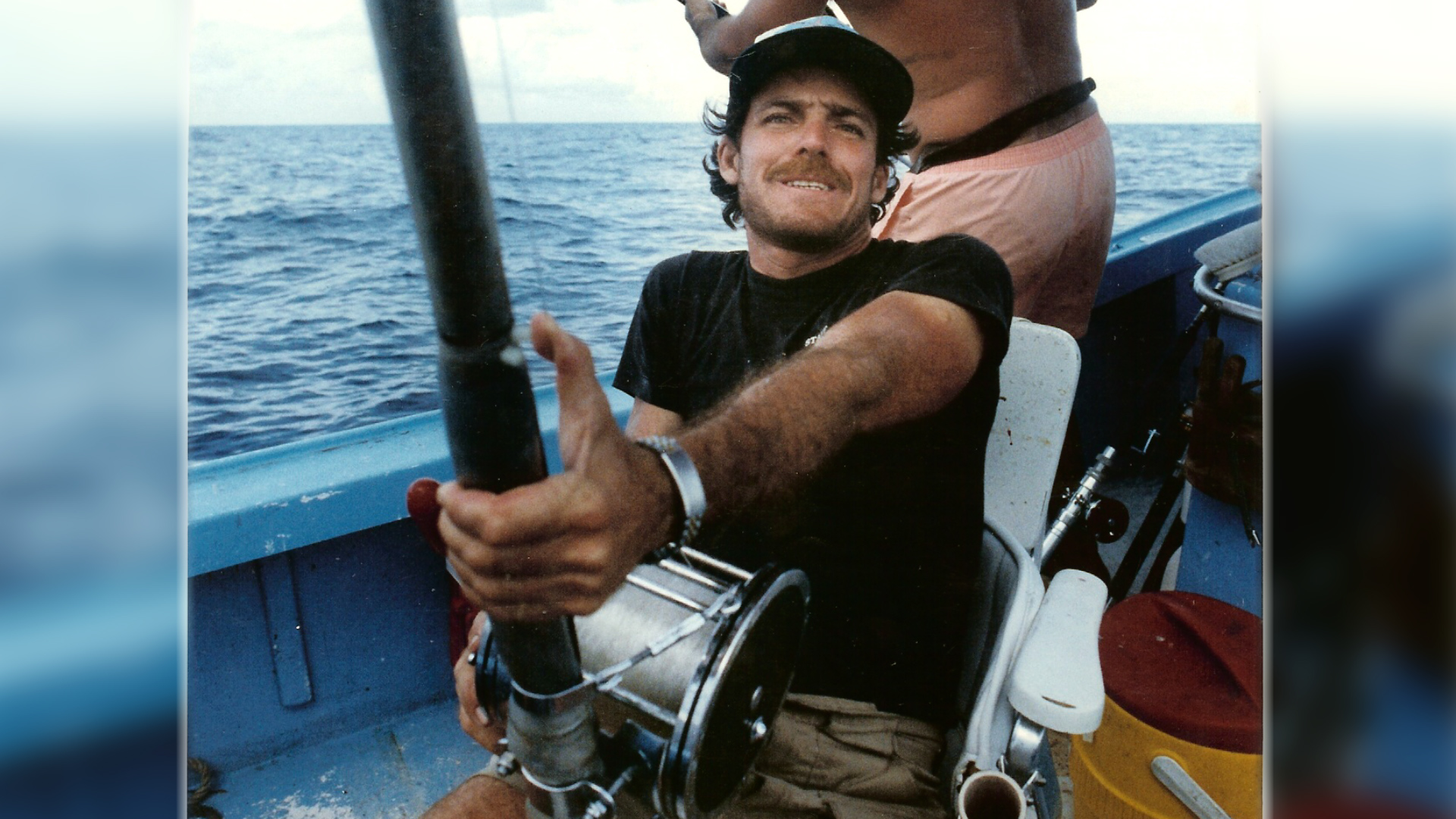

There’s also Shannon “Seaweed” Bustamante Jr., who grew up fishing alongside Rene and his father Shannon “Seaweed” Bustamante. During interviews, he’s seen sitting next to his own son, Dante. We cut between Jimbo, Seaweed Jr., and other locals who knew Rene, who knew South Beach, pictured alongside archival footage of Rene catching and swimming with sharks, interspersed with interviews from local reporters. Shark fishing, or sharking, as a sport, is not something people are generally familiar enough with to think that it would have its own Michael Jordan. But for those who knew him, like Jimbo, Rene was Michael. “I’ve taught a lot of kids, and they become good,” he says, back on the pier, the spitting image of a salty and seasoned sharker. “They become better than me. And Rene was one of them. [He] became one of the greatest shark fisherman in the United States,” Hammer says on the pier. “He proved it every day… he died proving it.”

I grew up in Miami. I attended Marjory Stoneman Douglas Elementary School, named after the journalist turned asexual environmental crusader, and then I went to Miami Dade College for film for two semesters before dropping out. That’s where I met Robbie Ramos, somewhat embarrassingly. The short I made during the first semester somehow made it to the Miami Film Festival student competition. Possessed by the delusions of grandeur that come with being a writer and the God complex of a 21-year-old, you would have thought I was on the red carpet of Cannes the way I acted like my shit didn’t stink. I got wasted at the open bar reception at The Standard on opening night off a pitcher of sangria and tequila shots. I left halfway through Jason Reitman’s “Tully” at the Olympia Theater in Downtown, but it didn’t matter to me. The only thing that mattered to me was the Cinemaslam, the student film screening the next morning.

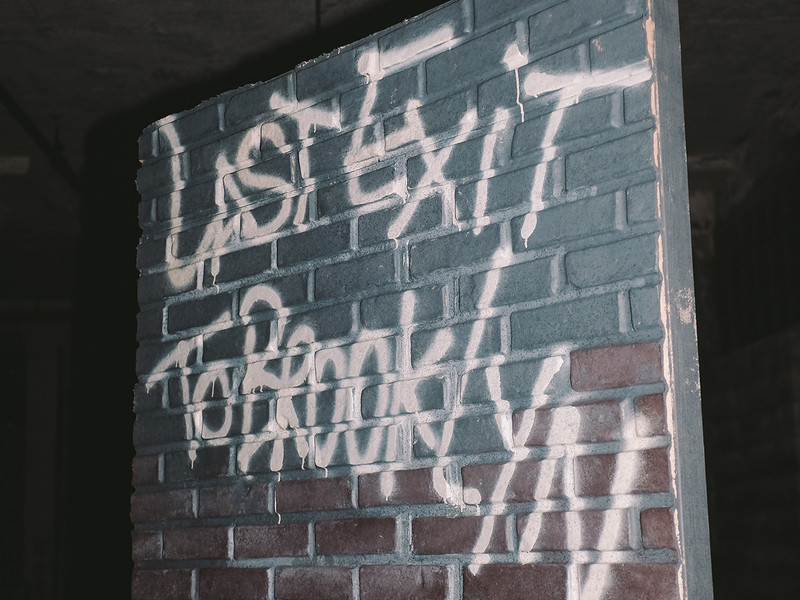

It was at the Tower Theater in the heart of Little Havana on Calle Ocho. No part of me expected to win. Everyone else was showing thesis projects, but my film was done as part of Film Production 1, which meant we didn’t use sound equipment and couldn’t leave campus. It was exactly what you’d expect in a student film screening. The film that stood out belonged to Robbie and his producer Pedro Gomez. It was the short film version of what became their feature documentary, South Beach Shark Club. I was blown away. I’ve since found that it’s rare to feel that in a theater during a screening.To think something a peer of yours has made isn’t just interesting or technically sound, but also so fucking cool, is special.

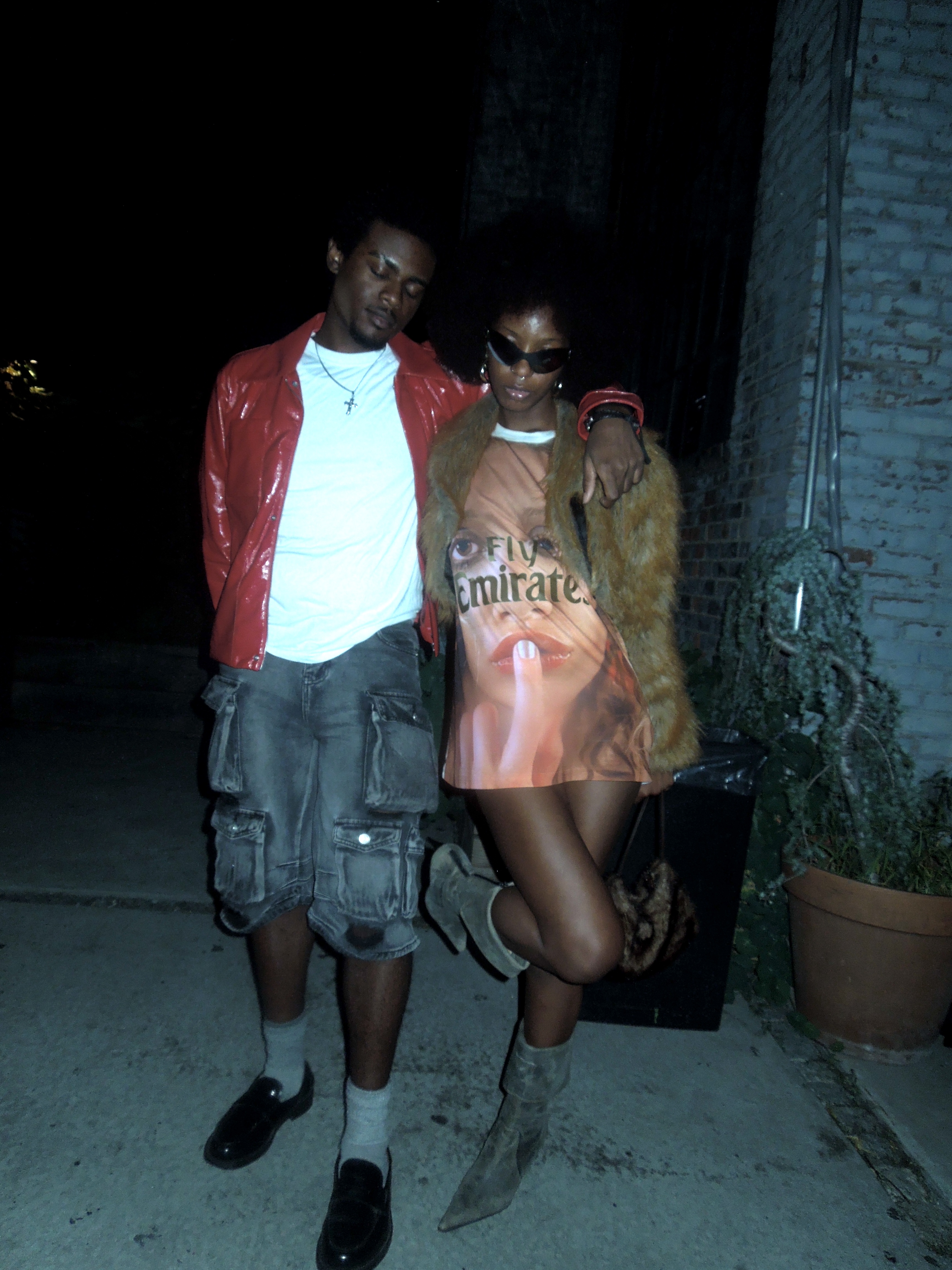

South Beach Shark Club won Cinemaslam, of course. Immediately afterward, I went up to congratulate them. To me, they were rock stars who just killed a set. I befriended them. And for the rest of that weekend, the three of us partied like the college students we were. It’s a tradition we’ve more or less continued anytime the three of us find ourselves in some stuffy ‘Miami filmmaker’ this-or-that, which happens more often than you’d think. Between us is a type of kinship, a mutual sense of being an outsider.

When I moved back to Florida, I hit up Pedro and asked if he and Robbie could take me fishing to write about the South Beach Shark Club. They said yes. On this particular Tuesday, it was 86 degrees and blazing hot — but still, not yet humid. A perfect Miami day. We weren’t sure if we’d be able to catch anything, but nevertheless, I’d finally get a feel for what they’d been doing for the last six years.