Open World

Tell me about your work.

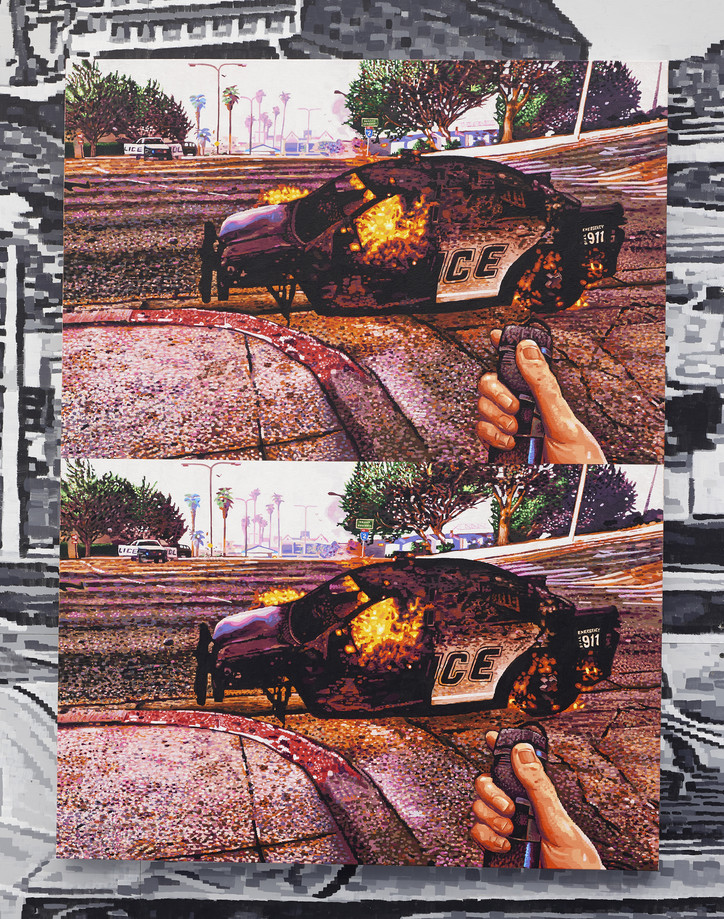

For the last two years, I’ve been making paintings that are sort of inspired by the digital world, in the broadest sense, before being more digital collage aesthetics, like Photoshop languages and traditional painting. So, trying to transform some of those digital gestures into gestures on the canvas. And then more recently I’ve been honing in a bit more and being a little more specific about what types of digital languages I’m painting from. The show that’s up at The Hole right now is exclusively from a game that came out in 2013, Grand Theft Auto 5, which is super popular—I think it’s the best-selling video game of all time. The reason I wanted drawn to it was because of how expansive it is—it’s an open world fan-box kind of game where players can kind of do whatever they want within that world; it’s not like a narrative that’s on rails—it’s more of a choose-your-own-adventure, there’s an immense amount of freedom in that. There’s also a great deal of beauty in the game—it’s like this parallel, bizarro Los Angelos—but there’s just amazing lighting and modeling and things like that—it really does feel like a world that you enter into, which is sort of a pre-cursor to virtual reality, maybe. To explore these kinds of exciting, new digital frontier ideas through painting is exciting for me.

Do you play video games?

I sure do, yeah. It’s part of the research now, but before I was making paintings from video games, I was still playing them, too. My relationship with video games goes all over the map, whether I’m obsessed with a game and really immersing myself in it or if it’s just like ten minutes of Rocket League or MarioKart or something that feels more arcade-y.

I love art that comes from video games. My brothers were gamers—I find it very strange when people aren’t into video games, just because they’re so everywhere. I remember when Grand Theft Auto came out and it was such an interesting concept, because I feel like it was one of the first open world games—there’s something about that open world concept.

There’s that game Second Life that got a lot of discourse, too. I never played that because it was on PC, but that had similar game play features, kind of like you can live your own life within this world, and it’s not like the game is telling you what, exactly, you should do.

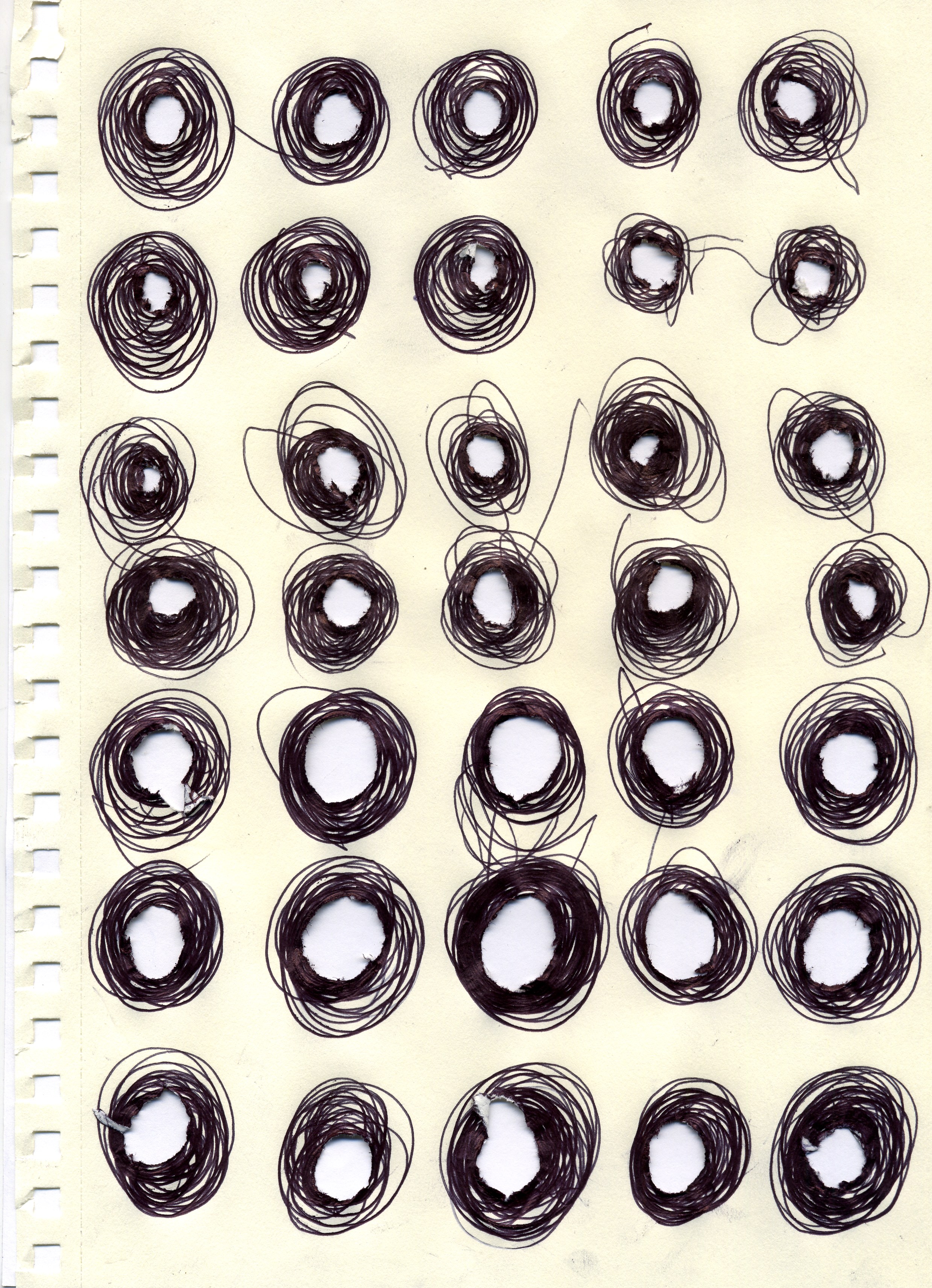

I love the use of repetition and the focus on cars—that, to me was really incredible. What is repetition for you—how are you using that, why are you using that?

That’s a really good question. It was good timing too because the Warhol show is up at the Whitney right now, so I got to see that, but it was nice that it was open during the opening of my show, because Warhol was one who was using repetition in a really interesting way through screenprinting and I’m doing it through painting. To me, I’m interested in painting images more than once to subvert that idea that paintings are these precious, unique objects with auras, you know what I mean? In a way, they are—none of the copies I do are exactly the same, so maybe I’m not necessarily trying to subvert it, but I’m playing with that idea. If you look at a jpeg of one of these paintings, it looks like a simple tile function in Photoshop, from faraway they look like a very simple drag-and-drop gesture, not something that is painstakingly reproduced by the human hand.

Also, painting the same thing over and over again is almost like when you say the same word over and over again—it begins to lose its meaning, it becomes abstracted in a way, psychologically. That happens to me when I’m painting—I don’t think, ‘I’m painting a tire,’ it’s just like, ‘Here’s a pink brushstroke on top of a gray brushstroke.’ I guess a lot of painters think that way when they’re painting, but when you’re painting the same thing over and over again, you get to that meditative headspace even more. That’s interesting and engaging for me.

'Buck and Stream' and 'Five Star Jump.'

It feels important that it’s connected to a digital landscape. There’s something about this digitization—it almost felt like you were walking into the actual internet when you were entering your show. How did you end up coming up with the immersive element of it?

I think this is my most ambitious show in terms of the scale of the installation. I was interested in the idea of the viewer needing to experience it in person, what with Instagram and jpegs. People always say, 'Oh you need to see a painting in person,' but I also feel like with phones, now you really do get a sense of what the painting is like through this 4-inch screen in our pockets. I like the idea of the painting being so big that you walk into it and it surrounds you, which I think you were alluding to—it’s kind of like playing Grand Theft Auto, you’re no longer in our world, you’re in this digital world. So, in the case of the exhibition, you’re in this painted world, which references the digital world. I’m really interested in all sorts of popular culture and entertainment and I like to paint from that—I go to the movies a lot and I love seeing movies in IMAX because the screen is bigger and it feels like your in this tiny little seat that’s getting swallowed up by that rectangle. I’m wondering, can painting compete with an IMAX screen or 3-D movies or virtual reality? Or not compete, maybe, but how do I paint in a way that responds to other ways that images are being consumed now?

Have you worked with digital art? What is your opinion on it?

I haven’t, no. You know, I enjoy it, but I don’t know—it’s weird because I’m making these paintings from these digital worlds, but I don’t love spending a long time on a computer. I like playing video games and watching movies and stuff, but in terms of the making, you can imagine the paintings take a while to make. I guess I would just rather spend that time doing something physical with my hands—not that making works digitally can’t be physical, I just think, in the end, I’m finding ways to continue to make painting exciting for me.

There’s this idea of a car crash happening, or destruction—it almost felt kind of violent in a way.

It’s hard to make work about video games without being aware of violence. Some of the previous work I had done were paintings from early first-person shooter imagery, like Doom 2 or Wolfenstein 3D—early pixelated violence. That type of violence is different from violence in movies because you’re the one controlling it, which I think is different psychologically, the activity of it. Then the painting is not interactive, it’s a static image—but I guess paintings are always interactive, because viewers are interacting with it in some way.

In Grand Theft Auto, you’re constantly being chased by the police, whether it’s sideswiping a car on accident or hitting a pedestrian, or maybe you’re doing a mission that involves a violent act. I mean, it’s fun to do these things—they’re not the sort of thing you want to do in our world, but in that world, there are no ramifications for your actions. So, you can drive your car off a cliff and the car explodes and you die but you just wake up instantly at the hospital and do it all over again. There’s this kind of digital immortality that supersedes the violence, death and destruction. It’s just something that’s a game-ender, but just another chapter in the game. It’s not something you’d play with in the real world, but it’s something that you get to do in this virtual one.

It’s such an interesting impulse toward mayhem and chaos where it’s like weirdly fun. I always feel like it’s a specifically male thing for some reason—boys just love chaos and going crazy.

It’s funny because I like to drive my car fast in the real world, but I do it in a way that’s like, what’s the fastest I can drive without getting pulled over? Or if I do get pulled over it’s borderline ‘Can I get out of this?' versus like I said in the video game, there’s no negative—you can just wake up again and get in a shoot-out.

'Jet and Bridge,' and 'Comet in Canyon.'

I love the concept of no consequences. Do you feel like there’s a sense of mortality that you’re tapping into?

Maybe. Maybe the digital immortality makes you think about real-life mortality, because all of our stories have a similar ending in that way—we’re all going to die in the real world in some way. But again, there’s this playfulness with death in video games—it’s just really not that big of a deal. So, have fun with it.

What's your favorite video game right now?

I’ve been playing this new Red Dead Redemption game. It’s made by the same developers as Grand Theft Auto, so it feels Sandbox-y, and it’s very open world, but it’s weird because it’s so slow—it’s in the Wild West so you’re on a horse all the time, whereas in Grand Theft Auto you’re stealing jets. I like to bounce back and forth between them—it feels like I’m time-traveling. The gameplay is so similar, but the worlds are so different. And in this game, there are more consequences—there’s a morality thing where your character, if they do things that are looked upon positively, and if they do illicit, illegal things, they get a bad reputation and people run away from you in town. It's like the developers are starting to think about, 'Well, what if there are consequences in these digital spaces that we’re creating and how does that change how we play the game?' It’s changing how I play the game, because I’m trying to be good, and then you might accidentally shoot someone and then you have to earn enough money to pay off your bounty—it’s just such a different way of doing things.

The thing about video games—I don’t know if anyone even says this anymore—but back when I was growing up there was always this outcry of people saying that it was negatively shaping young minds. How do you feel about that?

I have mixed feelings on it. That was a very 1990s moment, but I have heard these rippling waves of that conversation. I think a lot of it has to do with all the mass shootings that have been happening—I think we’re all so confused and heartbroken over them that it makes sense that people turn to the violence in video games as a potential motive. I think it’s a bit farfetched—I think there are more obvious things to address before violent video games.

It’s one of those funny things where the argument can go either way, because you can argue that by playing the video game you’re actually getting those violent impulses out of your system—they’re like an outlet—but then you can also argue the other side convincingly.

I would also venture a guess that the people making that argument aren’t playing video games—they don’t get that you can do these really violent things in the video game and know that that’s fictional, and know that hurting people in the real world is awful and you’ll feel awful if you do it and you shouldn’t. I think it’s people saying that from the outside.

'Boulder and Sunset' and 'Car Crash.'

I was actually talking to a little kid about this—his mom doesn’t allow him to play violent video games so he plays mostly Minecraft, but even Minecraft has a little bit of violence in it. It’s just inevitable with these adversarial situations. I remember thinking about it, even in Mario you have to destroy the villain—it’s just the nature of a plot.

Even in other genres, like racing games you’re bashing up against other cars. I play sports video games from time to time—I’ll play an NHL game—hockey is my favorite sport, and it's pretty violent, so it gets violent in the game. It’s interesting too to compare it to movies, because movies aren’t talked about as being super violent, but how many movies have guns in them versus how often do you see a gun in real life? Dustin Hoffman made the point to not be in any movies where his character has to use a gun, and that’s a pretty wild move for an actor to do, because probably more than half the movies out there have guns in them and he just thought you could have more subtle interactions with characters in the movie without a gun, which is probably true.

I kind of do wish there were more video games that had less violence. I remember there was this game in the '90s on PlayStation about making soup—you would use your controller to chop the carrots, and you wanted to make sure it didn’t boil over. It would be nice if there were more mundane options for video games, too.

I personally really like it when people embrace the digital in art.

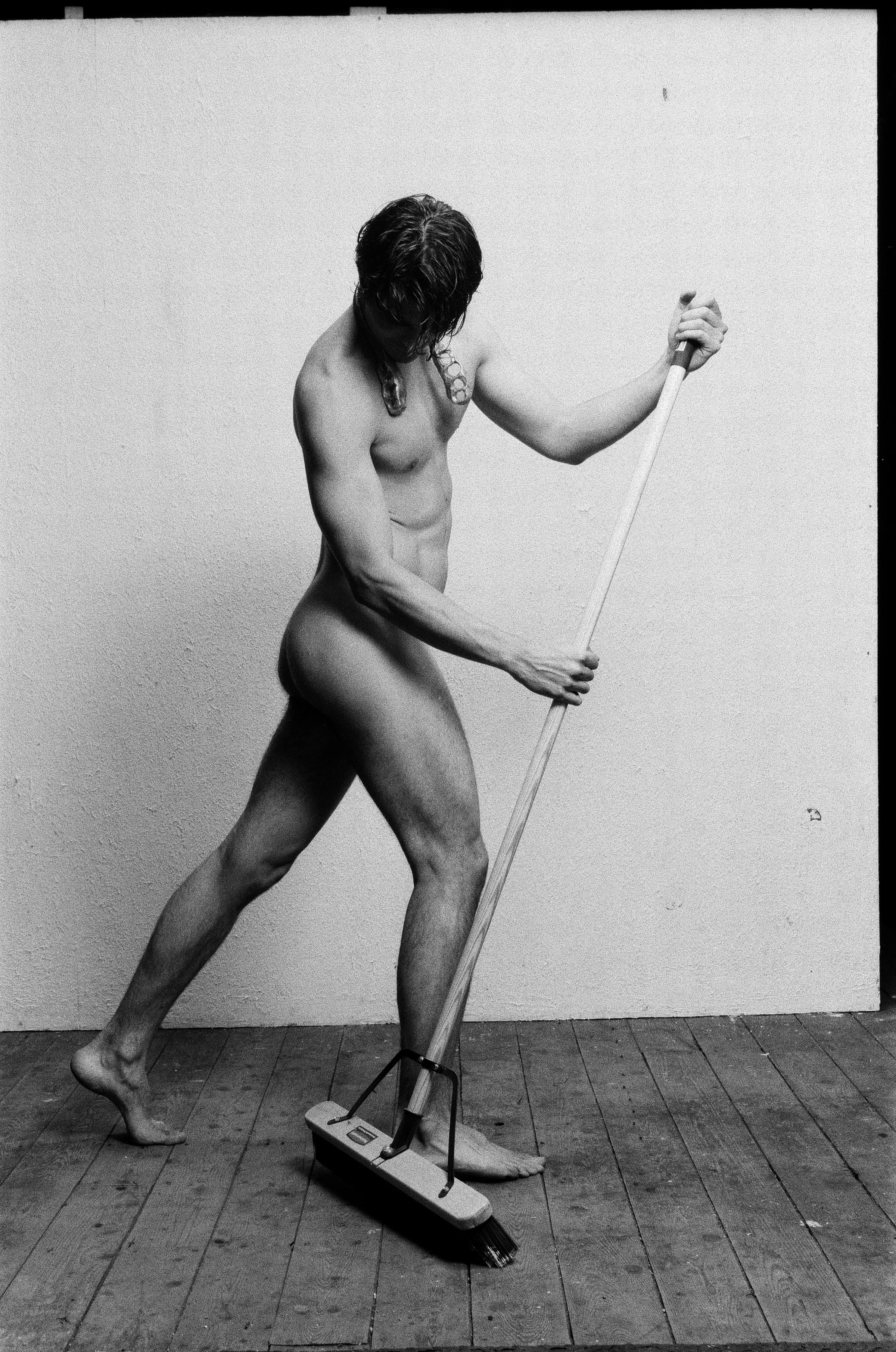

I mean, it’s everywhere. Painting can get pretty old-fashioned feeing pretty quick—I feel like it’s good to look at what’s happening now, and sometimes those things will feel alien on a canvas. It’s like, 'Whoa that’s weird to see that image painted by hand,' because we’re used to, historically, pastoral landscapes and reclining nudes—it’s just nice to inject some more current things in them. There are so many strategies other than looking at digital imagery, but that’s one thing that’s exciting for me, as a viewer, too, when something feels startlingly new.

It’s startlingly new and yet not at all. It really is mundane to us, but it makes you look at it differently—you realize it’s kind of cool.

I like the everyday-ness of it. I think of those train station paintings that Monet was making, and that being like a new technology, was—not shocking—but remarkable to see in painting in the 1880s.

'Customizable Realities' will be on view at The Hole in New York City through February 10.

Lead image: 'Pipe Bomb and Police Car.' All photos courtesy of the gallery.