ORCHID.seasons

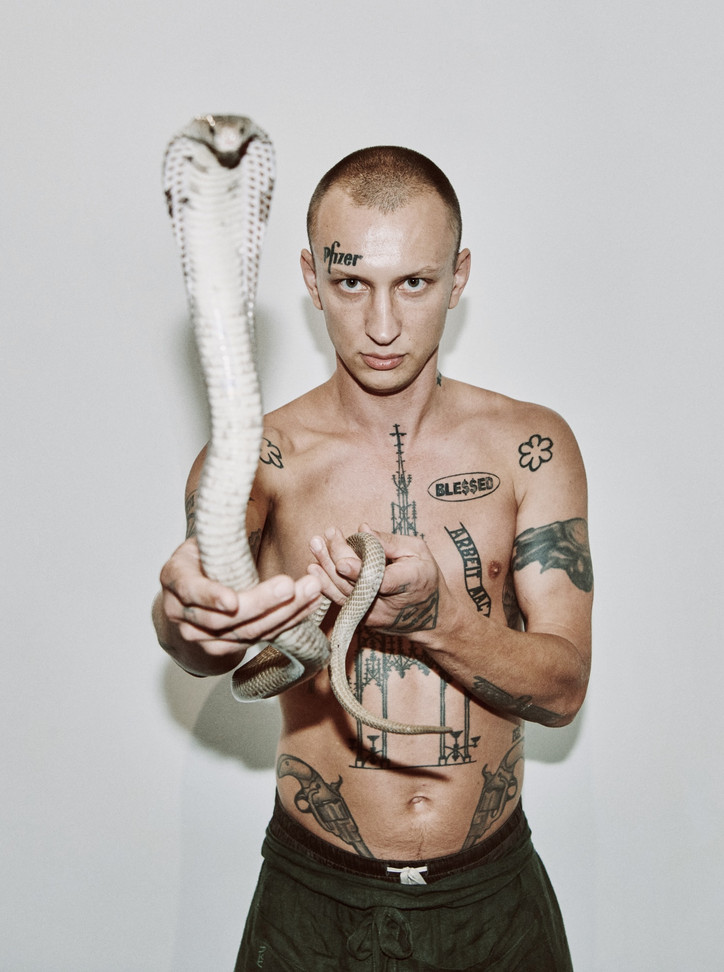

Earlier this week, Morrocco walked us through his new exhibition. Read our interview, below.

Tell me about the exhibition. What’s it about?

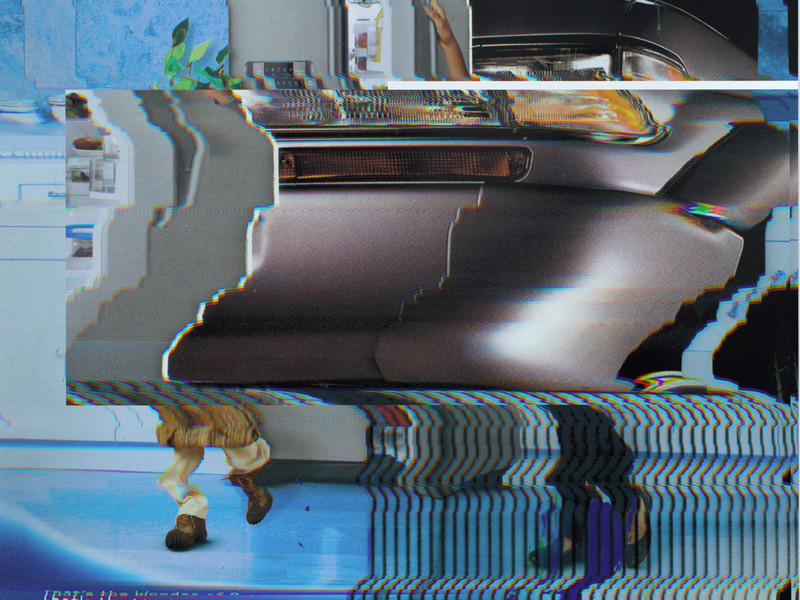

What I decided a year ago was that I wanted to do a piece of art that discussed the seasons—something that was different than what was expected of a gallery exhibition. I wanted it to be inclusive of people who weren’t in New York, which is why there is an Instagram component as well. So, I decided on a seasonal show mostly because I wanted to talk about photography’s relationship to light and time, and I thought that kind of reinforced it. The reason the seasons happen is because the earth is pointed 23 and a half degrees towards the north star, and so, when the earth goes around the sun, it changes the angle which the sun is reflected. I made these photographs with that in mind.

Also, I started this work around the time that Ellsworth Kelly died. It was really interesting that so few people discussed his work in regard to contemporary queer ideas. When you think about queer art, you think about people like Robert Mapplethorpe, but you never really think about Ellsworth Kelly within that canon. And I was like, “Why is that?” My early work was so much about the queer canon, but I wanted to open that up from the perspective of photography.

Is that you in all of the photos?

Yes, these are all self-portraits. I wanted to think about photography as three different things: landscape, portrait and still life. So, all of them are technically self-portraits.

Why did you choose to use this form of installation?

So much of the format of this show is about how a physical space relates to a virtual space. There’s something about the way that I wanted these pieces to function. I wanted them to be purely installation, so it sort of negates this idea that they are collectable items.

Right. You can’t just take them off the wall—they’re like stickers. In that way, it’s unreproducible. So, it has a lifespan.

It’s ephemeral.

Like the seasons?

Yeah, and the way things work on the internet. I wanted to talk about the way that the gallery functions now: a lot of people are having more and more trouble bringing people into gallery spaces. For example, the MET has super low numbers. There’s a major focus on putting things online, but it’s really hard to figure out how to do that. I thought it would be a good idea to have the opening be the time when people come to see the work, but if you miss this show you can go see the next one in a few months, or on Instagram.

So, it’s not as exclusive.

Exactly. I think everything has to function differently. You have to be able to do the physical things as well as virtual things. For people born in the last ten twenty years, their virtual worlds are just as important as their physical, real ones. And that’s why the internet is so important. It makes it so I don’t have to support my work on a whole ecosystem of people who don’t get paid. You had people like professors in undergrad who are constantly condemning the internet, but on the other hand, there’s people who think its great.

What do you think?

It’s just new, and people don’t know how to deal with it yet.

You use the phrase “queer economies of being.” Can you talk about what that means and what happens when anonymity comes into play?

Within any particular structure, whether that's queer people, straight people or non-binary, there’s an economy of what people value or what defines someone as queer. In another interview, I was talking about how a lot of people wanted to shove that queer canon down my throat. I was making work within that vein, but whenever I didn't know a particular artists they were like, “Oh why don't you know this?” I mean, I can't know every queer artist that ever existed, I'm sorry! And I'm also interested in non-queer art. So, I wanted to give myself the space to pull back from these visual economies that “make us” queer and think about visual language in more abstract way.

So, obscuring your face using a bodysuit—is that you taking away the context?

Yeah, it’s sort of meditative in that way. I couldn't see anything and it's almost like I didn’t exist, but the nature is there. I could feel the dirt through my feet, and the thorns cutting into my skin.

What interests you about the biological process of seeing? Usually, when we talk about seeing bodies, we’re talking about the theoretical and cultural process of how bodies are consumed in media.

I was thinking about how Newton proceeded from a physical standpoint. Basically, what he did was look through this prism, see the colors of the rainbow and organize them into the color wheel: primary colors and tertiary colors, etc. Out of that the whole system, color theory evolved for the next 400 years. But it all came from this physicist who was just looking at how it was all happening. Some people think that if the earth was in a different place in the universe—if it was closer or further to light—there might be a place out there where all the “green” foliage is a different color. So, I think the physical placement of things—the physical reality of them—really matters in terms of how stuff gets seen and understood.

Going off the importance of physical placement, why did you choose to shoot this in nature as opposed to a city or studio space?

Well, first, I guess I wanted to make this point that perception is created by light. And what better way to say that then through the season? The best way to express that is through nature.

You noted that there were certain cultural conventions that you were responding to using the four seasons of a gallery opening, instead of just one month. What cultural conventions? Is it an art world thing?

It’s definitely an art world thing. I mean, if you guys spend time in the art world, it's like, “Oh, here's my 40 day show,” and if you miss that, then oh well, maybe you'll see it in a museum in 20 years. I just really wanted to drive the attention towards the online space, because much more people can see it when it’s online. Why, when art can be accessible, would we keep it so private? What's the point?

What’s your goal? What do you want to do with this exhibit?

Best case scenario, someone walks away feeling inspired to be themselves. Like, go do literally whatever you want. I started taking photography very seriously when I was 20. So, over the past eight years, all I've done is create a space where I can do whatever I want and show it to people. It has led me to some really weird things, some really difficult things, but also to some really great things, too. Ultimately, I feel like—this is going to sound really cheesy—but what it led me to was myself, alone in the woods really enjoying who I am and what i do. I think that's what’s important.

'ORCHID.seasons is open now until September 15 at Crush Curatorial and via @matthew_morrocco on Instagram.

Photos courtesy of Crush Curatorial.